A Study on the Not-For-Profit Route to Olympic Gold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

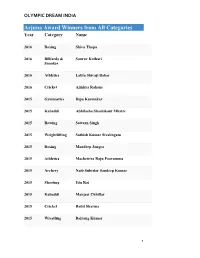

Arjuna Award Winners from All Categories Year Category Name

OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA Arjuna Award Winners from All Categories Year Category Name 2016 Boxing Shiva Thapa 2016 Billiards & Sourav Kothari Snooker 2016 Athletics Lalita Shivaji Babar 2016 Cricket Ajinkya Rahane 2015 Gymnastics Dipa Karmakar 2015 Kabaddi Abhilasha Shashikant Mhatre 2015 Rowing Sawarn Singh 2015 Weightlifting Sathish Kumar Sivalingam 2015 Boxing Mandeep Jangra 2015 Athletics Machettira Raju Poovamma 2015 Archery Naib Subedar Sandeep Kumar 2015 Shooting Jitu Rai 2015 Kabaddi Manjeet Chhillar 2015 Cricket Rohit Sharma 2015 Wrestling Bajrang Kumar 1 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2015 Wrestling Babita Kumari 2015 Wushu Yumnam Sanathoi Devi 2015 Swimming Sharath M. Gayakwad (Paralympic Swimming) 2015 RollerSkating Anup Kumar Yama 2015 Badminton Kidambi Srikanth Nammalwar 2015 Hockey Parattu Raveendran Sreejesh 2014 Weightlifting Renubala Chanu 2014 Archery Abhishek Verma 2014 Athletics Tintu Luka 2014 Cricket Ravichandran Ashwin 2014 Kabaddi Mamta Pujari 2014 Shooting Heena Sidhu 2014 Rowing Saji Thomas 2014 Wrestling Sunil Kumar Rana 2014 Volleyball Tom Joseph 2014 Squash Anaka Alankamony 2014 Basketball Geetu Anna Jose 2 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2014 Badminton Valiyaveetil Diju 2013 Hockey Saba Anjum 2013 Golf Gaganjeet Bhullar 2013 Athletics Ranjith Maheshwari (Athlete) 2013 Cricket Virat Kohli 2013 Archery Chekrovolu Swuro 2013 Badminton Pusarla Venkata Sindhu 2013 Billiards & Rupesh Shah Snooker 2013 Boxing Kavita Chahal 2013 Chess Abhijeet Gupta 2013 Shooting Rajkumari Rathore 2013 Squash Joshna Chinappa 2013 Wrestling Neha Rathi 2013 Wrestling Dharmender Dalal 2013 Athletics Amit Kumar Saroha 2012 Wrestling Narsingh Yadav 2012 Cricket Yuvraj Singh 3 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2012 Swimming Sandeep Sejwal 2012 Billiards & Aditya S. Mehta Snooker 2012 Judo Yashpal Solanki 2012 Boxing Vikas Krishan 2012 Badminton Ashwini Ponnappa 2012 Polo Samir Suhag 2012 Badminton Parupalli Kashyap 2012 Hockey Sardar Singh 2012 Kabaddi Anup Kumar 2012 Wrestling Rajinder Kumar 2012 Wrestling Geeta Phogat 2012 Wushu M. -

Greatest Sportperson India World

GREATEST SPORTPERSONS, GREATEST INDIAN SPORTSMEN AND SPORTSWOMEN GK.TAMILGOD.ORG /ebooks/sportspersons-greatest -indian-world-sportsmen-and-sportswomen-ebook65836 SPORTS SPORTSPERSON INDIAN, WORLD GK.TAMILGOD.ORG TAMILGOD.ORG GK SERIES FREE EBOOKS /tamilgodorg /c/TamilgodOrg TAMILGOD.ORG GK SERIES FREE EBOOKS SPORTPERSONS, INDIAN GREATEST SPORTSMEN & SPORTSWOMEN SPORTPERSONS OF WORLD Cristiano Ronaldo Tiger Woods Soccer Golf Portugal USA Lionel Messi Rafael Nadal Soccer Tennis Argentina Spain LeBron James Manny Pacquiao Basketball Boxer USA Philippines Roger Federer Serena Williams Tennis Tennis Switzerland USA Kevin Durant Maria Sharapova Basketball Tennis USA Russian Novak Djokovic Caroline Wozniacki Tennis Tennis Serbia Denmark Cam Newton Danica Sue Patrick American football Car racing USA USA Phil Mickelson Stacy Lewis Golf Golf USA USA Jordan Spieth Usain Bolt Golf Runner (100 m) USA Jamaica Kobe Bean Bryant Florence Grith-Joyner Basketball Runner (100 m) USA USA Lewis Hamilton Formula One racing United Kingdom TAMILGOD.ORG GK SERIES FREE EBOOKS Greatest Sportpersons GK.TAMILGOD.ORG TAMILGOD.ORG GK SERIES FREE EBOOKS SPORTPERSONS, INDIAN GREATEST SPORTSMEN & SPORTSWOMEN GREATEST SPORTSWOMEN (INDIA) Deepika Kumari Archery Jharkhand PT Usha Runner Kerala Anjum Chopra Cricket New Delhi Anju Bobby George Athletics Kerala Dipika Pallikal Squash Tamil Nadu Karnam Malleswari Weightlifting Andhra Pradesh Mithali Raj (Lady Sachin) Cricket Rajasthan Sania Mirza Tennis Maharashtra Saina Nehwal Badminton Haryana MC Mary Kom Boxing Manipur TAMILGOD.ORG -

01 CURRENT AFFAIRS for the PERIOD NOV-2017 to OCT-2018

RADIAN IAS ACADEMY (CHENNAI - 9840398093 MADURAI - 9840433955) -1- www.radianiasacademy.org PART - 01 CURRENT AFFAIRS FOR THE PERIOD NOV -20 17 to OCT -2018 1) Who among the following Indian golfers won the Fiji 6) IMPRINT programme of Union HRD Ministry refers to International tournament in August 2018? which of the following? a) Shiv Kapur b) Anirban Lahiri மதிய மனதவள ேமபா அைமசகதி c) Rahil Gangjee d) Gaganjeet Bhullar IMPRINT நிகசி பவவனவறி எைத ஆக 2018 பஜி சவேதச ேபாய ெவறி றிகிற? ெபற பவ இதிய ேகா வ ர யா? a) Involving Research Innovation and Training a) சி க b) அனப லகி b) Impacting Research Innovation and Technology c) Inculcating Research Innovation and Technology c) ரஹி கஜி d) ககஜ ல d) Industrialising Research Innovation and Training 2) Which country has topped the United Nation’s 7) Indian-Australian mathematician who is among the four E-Government Development Index released in July winners of mathematics’ Fields medal announced in 2018? August 2018: a) Denmark b) Hungary a) Prabhu Aiyyar b) Akshay Venkatesh c) Norway d) Ireland c) Vaibhav Kumaresh d) Vikram Sathyanathan ஜூைல 2018 ெவளயடபட ஐகிய நாகள 2018 ஆக அறிவகபட கணத மி-ேமபா றிய தைமயான நா எ? லைமபசிகான நா ெவறியாளகள இதிய- a) ெடமா b) ஹேக ஆதிேரலிய கணதவயலாள ஒவ யா? c) நாேவ d) அயலா a) பர அய b) அ ஷ ெவகேட 3) Pingali Venkayya is remembered for which of the c) d) following? ைவப மேர வர சயநாத a) He designed the map of India after the integration of 8) Nokrek Biosphere Reserve is in: princely states following independence a) Sikkim b) Manipur c) Mizoram d) Nagaland b) He designed the first postage -

List of Major Sports Awards in India & Winners Sports Awards And

List of Major Sports Awards in India & Winners Sports Awards and accolades are an important section of General Awareness section. It is important to prepare for the general awareness section. Static GK is more popular than current affairs in General awareness section. Aspirants must be well versed with topics from history, geography, science, environment and sports will be able to clear any competitive exam. Major Sports Awards in India: There are two old proverbs that go well with Sports - “Practice makes a man perfect” and “All work and no play makes jack a dull boy”. All of us have played some sport or the other during school days. While boys played games like cricket, football, kabbadi, and a lot of indoor games, girls too participated in a lot of sports. Schools and Colleges often give trophies and medals to sports winners or simply give them a participation certificate. While speaking of sports there are several awards for state level and national level players. The government of India and respective state governments give awards to all sports players. There are several awards like Rajiv Gandhi Khel Ratna award, Arjuna Award, Dronacharya Award and Dyanchand Award. Lets look at winners of various sports awards over the years. Please note that the Major sports awards are given to national level and international level sports players. Rajiv Gandhi Khel Ratna Award – Sports Awards in India Rajiv Gandhi Khel Ratna is the highest sports award given to the most outstanding performance in the field of sports at national or international level. • As of 2017, winners of this award receive a cash prize of Rs. -

Geet Sethi : an Obsessive-Compulsive Billiards Champion

“You Don’t Have To Be Great To Start, But You Have To Start To May 16, 2021 Be Great.” –– Zig Ziglar [email protected] 3 THE FACT CORNER BRAIN TEASERS English Proverbs and Meanings 1 Q.There are several books on a bookshelf. If were an hour later. What time is it now? * You are never too old to learn. have any money when you're one book is the 4th from the left and 6th You can always learn something old. from the right, how many books are on the 5 Q. There are two ducks in front of two other new, no matter how old you are. shelf? ducks. There are two ducks behind two * What the eye doesn't see, the other ducks. There are two ducks beside * You can lead a horse to water heart doesn't grieve over. 2 Q. What do you get when you divide 30 by 1/2 two other ducks. How many ducks are but you can't make it drink. If a person doesn't know about and add 10? there? You can offer somebody an something, it cannot hurt them. opportunity to do something but 3 Q. I am a three digit number. My tens digit is 6 Q. Can you arrange four nines to make it you can't force them to do it. * Who makes himself a sheep will five more than my ones digit. My hundreds equal to 100. be eaten by the wolves. digit is eight less than my tens digit. What * You can't teach an old dog new Possible interpretation: an easi number am I? 7 Q . -

Games and Sports : a Gateway of Women's Empowerment in India

Games And Sports : A Gateway Of Women’s Empowerment In India Dr. Krishnendu Pradhan ABSTRACT “Sport has huge potential to empower women and girls” - Remarks by Lakshmi Puri; UN Assistant Secretary-General and UN Women Deputy Executive Director. The purpose of this paper attempts to shed light the status of women’s empowerment in India through games and sports and highlights the issues and challenges of women empowerment in the field of physical education and sports. Sport is an integral part of the culture of almost every nation. However, its use to promote gender equity and empower girls and women is often overlooked because sport is not universally perceived as a suitable or desirable pursuit for girls and women. Today the empowerment of women in games and sports has become one of the most important concerns of 21st century. But practically women empowerment in games and sports is still an illusion of reality. It is observe in our day to day life how women become victimized by various social evils. Women empowerment is the vital instrument to expand women’s ability to have resources and to make strategic life choices. Empowerment of women in games and sports is essentially the process of upliftment of economic, social and political status of women, the traditionally underprivileged ones, in the society. Today sports and physical activity as a strategy for the empowerment of girls and women has been gaining recognition worldwide. Women could be empowered through education, sports and physical activities and by giving them equal opportunities in different walks of life. Research on sport, gender, and development indicates that sport can benefit girls and women by: Enhancing health and well-being, fostering self-esteem and empowerment, facilitating social inclusion and integration, challenging gender norms and providing opportunities for leadership and achievement. -

Introduction to Changing Life

Changing Life: 2 10 Q.1. (A) i. (C) ii. (D) iii. (B) iv. (A) (B) The incorrect pair is: Kapil Dev Billiards The corrected pair is: Kapil Dev Cricket Q.2. (A) i. Objective of Newspapers Shape up public Directing public Carry out public Keep a watch on opinion opinion towards education government machinery constructive work and lead it. ii. Raising funds for draught Raising funds for flood affected people. affected people. The newly added functions of the newspapers Organizing or sponsoring Helping meritorious students from lower cultural programmes income groups for higher education (B) i. a. India has been participating in Asiad and Olympic games. b. At the Olympics (of 2000), Karnam Malleswari won a medal for weight-lifting. c. She was the first Indian woman to win a medal at the Olympics. d. Thereafter, India’s representation began to rise in various Olympic Games such as hockey, badminton, tennis, swimming, weight lifting and archery. ii. a. Theatre and films are considered as important aspects of Indian life. b. Initially, plays were very long, sometimes running through an entire night. c. But now, the form, technique and duration of plays have undergone a great change. d. People from different walks of life participate in the dramas. e. On one hand, the importance of ‘Musicals’ has declined. On the other hand, the political and social subjects have replaced the earlier mythological and historical themes. Q.3. (A) i. a. The age of black and white movies has been succeeded by the age of coloured movies. With this, film shooting locales have moved abroad and hence viewers can now watch different exotic places in foreign countries. -

Solved SSC GD 12Th Feb 2019 Shift-1 Paper with Solutions

SSC GD Exam P r e v i o u s Paper Reasoning Instructions For the following questions answer them individually Question 1 The statements below are followed by two conclusions labeled I and II. Assuming that the information in the statements is true, even if it appears to be at variance with generally established facts, decide which conclusion(s) logically and definitely follow(s) from the information given in the statements. Statements: 1. All pupils are crows. 2. All crows are cats. Conclusion I. All cats are crows. II. Some crows are pupils. A Only conclusion I follows. B Both conclusions follow. C Either conclusion I or conclusion II follows. D Only conclusion II follows. Answer: D Question 2 Select the option that is related to the third term in the same way as the second term is related to the first term. Lethargy : Alertness :: Peace : ? A Cheer B Chaos C Chat D Choose Answer: B Question 3 Select the option that is related to the third number in the same way as the second number is related to the first number. 22 : 441 :: 13 : ? A 221 B 144 C 275 D 169 Answer: B . Question 4 Select the correct option that will fill in the blank and complete the series. RTN, SRO, TPP, UNQ, ? A VJR B VLP C VLR D VIP Answer: C Question 5 There is only one runway which will be used by seven flights one by one. P and Q will use the runway neither first nor last. S will use it second after R. -

Schools Rd Th Facts of India Sports(Grade 3 – 12 )

SURAJ Schools rd th Facts of India Sports(Grade 3 – 12 ) * Chess was originally named “Chaturanga” or “Chaturaangam” meaning intelligent or Smart. This game was invented in India. * Sachin Tendulkar fielded for Pakistan once – Ahead of a Test series in 1987, India and Pakistan were playing an exhibition match where Imran Khan‟s team was short on fielders. It was then that a 13-year-old Sachin was asked to field for Pakistan. * The Most awaited T20- IPL cricket series also known as India‟s “Indian Premier League” is the 2nd- plushest sports league after the “National Basket Ball Association” /“NBA” of the United States. * PT Usha started her career with a scholarship of Rs 250 – Usha had faced poverty and ill health as a child. But her talent won her a scholarship of Rs 250 per month, allowing her to study in a sports school in Kannur, Kerala, where she trained and eventually became the “Queen of Track and Field” in India. * Playing cards often called a “Gambler‟s delight‟ was introduced in Eastern India and surprisingly first introduced as a family game before becoming a confluence for gambling joints * Major Dhyan Chand has a statue with 4 hands and 4 sticks in Austria – Known as the Wizard of Hockey, the legend was honoured by Austrian citizens in Vienna. They made a statue of him with 4 hands and 4 sticks to depict his magnificent skill and control with the ball. * The 1st Indian to have won the coveted Wimbledon Jr. Singles is Ramanathan Krishnan;He won over Ashley Cooper in the finals. -

PROFESSIONAL EXAMINATION BOARD Pre B.Ed./B.Ed.M.Ed./M.Ed./B.P.Ed./M.P.Ed

PROFESSIONAL EXAMINATION BOARD Pre B.Ed./B.Ed.M.Ed./M.Ed./B.P.Ed./M.P.Ed. Entrance Test: 2016 25th April 2016, 09:00 AM Topic: B.P.Ed.General Knowledge of Sports 1) Question Stimulus : Geet Sethi is associated with: / गीत सेठी इस खेल से संिधत है: Badminton / बैडिमंटन Billiards / िबिलयड्स Wrestling / कु ी Boxing / बांग Correct Answer :Billiards / िबिलयड्स 2) Question Stimulus : Sports Museum is situated at: / खेल संहालय यहाँ थत है: New Delhi / नई िदी Kolkata / कोलकाता Jalandhar / जालंधर Patiala / पिटयाला Correct Answer :Patiala / पिटयाला 3) Question Stimulus : The measurement of a handball court is: / हडबॉल कोट का माप है: 13 x 10m /13 x 10मी 18 x 9m / 18 x 9मी 1.40 x 55m / 91.40 x 55मी 40 x 20m / 40 x 20मी Correct Answer :40 x 20m / 40 x 20मी 4) Question Stimulus : ‘PingPong’ was the old name of : / 'िपंग पोगं ' इसका पुराना नाम था: Tennis / टेिनस TableTennis / टेबल टेिनस KhoKho / खोखो Badminton / बैडिमंटन Correct Answer :TableTennis / टेबल टेिनस 5) Question Stimulus : How many attempts are allowed in weight lifting? / वेट िलंग म िकतने यास की अनुमित दी जाती है? 4 3 2 1 Correct Answer :3 6) Question Stimulus : Which country hosts the Wimbledon tennis tournament? / कौन सा देश िवलडन टेिनस टू नामट आयोिजत करता है? Canada / कनाडा France / ांस England / इंगलड Sweden / ीडन Correct Answer :England / इंगलड 7) Question Stimulus : How many substitutions are allowed in Basketball? / बाे टबॉल म िकतने सटीूशन की अनुमित होती है? 2 5 6 Unlimited / असीिमत Correct Answer :Unlimited / असीिमत 8) Question Stimulus : The first Asian KhoKho Championship was held in: / थम एिशयाई खोखो चि पयनिशप इस वष म आयोिजत की गई थी: 1987 1990 1996 1914 Correct Answer :1996 9) Question Stimulus : In 4×100m relay race, the length of baton exchange zone is:/ 4×100 मीटर रले दौड़ म, बाटन िविनमय े की लंबाई होती है: 15 m/ 15मी 10 m/ 10मी 20 m/ 20मी 22 m/ 22मी Correct Answer :20 m/ 20मी 10) Question Stimulus : In Soccer, the penalty kick spot is marked at the distance of _____ from the goal line. -

Static GK Capsule 2017

AC Static GK Capsule 2017 Hello Dear AC Aspirants, Here we are providing best AC Static GK Capsule2017 keeping in mind of upcoming Competitive exams which cover General Awareness section . PLS find out the links of AffairsCloud Exam Capsule and also study the AC monthly capsules + pocket capsules which cover almost all questions of GA section. All the best for upcoming Exams with regards from AC Team. AC Static GK Capsule Static GK Capsule Contents SUPERLATIVES (WORLD & INDIA) ...................................................................................................................... 2 FIRST EVER(WORLD & INDIA) .............................................................................................................................. 5 WORLD GEOGRAPHY ................................................................................................................................................ 9 INDIA GEOGRAPHY.................................................................................................................................................. 14 INDIAN POLITY ......................................................................................................................................................... 32 INDIAN CULTURE ..................................................................................................................................................... 36 SPORTS ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

Effect of Idian Political System on Indian Sports

EFFECT OF IDIAN POLITICAL SYSTEM ON INDIAN SPORTS Raminder Kaur1 Gurpreet Kaur2 1Asstant Professor, Baba Fraid College Bathinda.(Punjab) India 2Asstant Professor, Baba Fraid College Bathinda.(Punjab) India ABSTRACT In 1978, UNESCO described sport and physical education as a “fundamental right for all”. But until today, the right to play and sport has too often been ignored or disrespected. Sport has a unique power to attract, mobilize and inspire. By its very nature, sport is about participation. It is about inclusion and citizenship. One of the drawbacks of industrial revolution is the sedentary lifestyle we have adapted which is directly linked to primary and secondary diseases, such as heart problems, high cholesterol, mental stress, high blood pressure and on top of all that is the environmental pollution, which is currently one of the risk factors of global magnitude. Sport leisure and recreation have become important dimensions in social and economic life. Social amenities such as the gymnasiums, fitness centers, play fields, social halls and swimming pools generate revenue for self-sustainability and therefore contribute to national development on two fronts. Research shows that investment into sport in developing countries is much less than in developed countries, as sport development is usually not a top priority in the national budget or in the education system of most developing countries. One may wonder that government of India pumping several crore rupees into the various sports bodies for promoting sports and encouraging the sportsmen but these sports bodies have become fertile ground for the politicians and ex-bureaucrats to make money. Key words: Fundamental Right, Political Interference & Indian Sports.