Gomal Nomads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern

SOCIOLINGUISTIC SURVEY OF NORTHERN PAKISTAN VOLUME 4 PASHTO, WANECI, ORMURI Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Volume 2 Languages of Northern Areas Volume 3 Hindko and Gujari Volume 4 Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri Volume 5 Languages of Chitral Series Editor Clare F. O’Leary, Ph.D. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 4 Pashto Waneci Ormuri Daniel G. Hallberg National Institute of Summer Institute Pakistani Studies of Quaid-i-Azam University Linguistics Copyright © 1992 NIPS and SIL Published by National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan and Summer Institute of Linguistics, West Eurasia Office Horsleys Green, High Wycombe, BUCKS HP14 3XL United Kingdom First published 1992 Reprinted 2004 ISBN 969-8023-14-3 Price, this volume: Rs.300/- Price, 5-volume set: Rs.1500/- To obtain copies of these volumes within Pakistan, contact: National Institute of Pakistan Studies Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan Phone: 92-51-2230791 Fax: 92-51-2230960 To obtain copies of these volumes outside of Pakistan, contact: International Academic Bookstore 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road Dallas, TX 75236, USA Phone: 1-972-708-7404 Fax: 1-972-708-7433 Internet: http://www.sil.org Email: [email protected] REFORMATTING FOR REPRINT BY R. CANDLIN. CONTENTS Preface.............................................................................................................vii Maps................................................................................................................ -

Tribal Belt and the Defence of British India: a Critical Appraisal of British Strategy in the North-West Frontier During the First World War

Tribal Belt and the Defence of British India: A Critical Appraisal of British Strategy in the North-West Frontier during the First World War Dr. Salman Bangash. “History is certainly being made in this corridor…and I am sure a great deal more history is going to be made there in the near future - perhaps in a rather unpleasant way, but anyway in an important way.” (Arnold J. Toynbee )1 Introduction No region of the British Empire afforded more grandeur, influence, power, status and prestige then India. The British prominence in India was unique and incomparable. For this very reason the security and safety of India became the prime objective of British Imperial foreign policy in India. India was the symbol of appealing, thriving, profitable and advantageous British Imperial greatness. Closely interlinked with the question of the imperial defence of India was the tribal belt2 or tribal areas in the North-West Frontier region inhabitant by Pashtun ethnic groups. The area was defined topographically as a strategic zone of defence, which had substantial geo-political and geo-strategic significance for the British rule in India. Tribal areas posed a complicated and multifaceted defence problem for the British in India during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Peace, stability and effective control in this sensitive area was vital and indispensable for the security and defence of India. Assistant Professor, Department of History, University of Peshawar, Pakistan 1 Arnold J. Toynbee, „Impressions of Afghanistan and Pakistan‟s North-West Frontier: In Relation to the Communist World,‟International Affairs, 37, No. 2 (April 1961), pp. -

SECURITY REPORT 2016 FATA Annual Security Report 2016

W W W . F R C . O R G . P K FATA ANNUAL SECURITY REPORT 2016 FATA Annual Security Report 2016 FATA ANNUAL SECURITY REPORT 2016 Noshad Ali Mahsud Muhammad Mateen Maida Aslam Irfan-U-Din Dr. Syed Adnan Ali Shah Bukhari Map of FATA I II II III V 1 1 4 8 8 8 9 9 9 10 10 11 23 23 24 27 28 29 FATA Annual Security Report 2016 Map of FATA I FATA Annual Security Report 2016 About FATA Research Centre FATA Research Centre (FRC) is a non-partisan, non-political and non- governmental research organization based in Islamabad. It is the first ever think-tank that specifically focuses on the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of Pakistan in its entirety. The purpose of establishing the FRC is to create a better understanding about the conflict in FATA among the concerned stake holders through undertaking independent, impartial and objective research and analysis. The FRC endeavors to create awareness among all segments of the Pakistani society and the government to jointly strive for a peaceful, tolerant and progressive FATA. FATA Annual Security Report FATA Annual Security Report shows recent trends of militant violence in FATA, such as the number and type of militant attacks, tactics and strategies used by the militants and the resultant casualties. The objective of this security report is to outline, categorize, and provide comparative analysis of all forms and shapes of violent extremism, role of militant groups and the scale of militant activities on quarterly basis. This report is the result of regular monitoring of militant and counter-militant activities while employing primary and secondary sources. -

19 October 2020 "Generated on Refers to the Date on Which the User Accessed the List and Not the Last Date of Substantive Update to the List

Res. 1988 (2011) List The List established and maintained pursuant to Security Council res. 1988 (2011) Generated on: 19 October 2020 "Generated on refers to the date on which the user accessed the list and not the last date of substantive update to the list. Information on the substantive list updates are provided on the Council / Committee’s website." Composition of the List The list consists of the two sections specified below: A. Individuals B. Entities and other groups Information about de-listing may be found at: https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/ombudsperson (for res. 1267) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/delisting (for other Committees) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/2231/list (for res. 2231) A. Individuals TAi.155 Name: 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: ABBASIN 3: na 4: na ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻌﺰﻳﺰ ﻋﺒﺎﺳﯿﻦ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1969 POB: Sheykhan Village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: Abdul Aziz Mahsud Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: na Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 4 Oct. 2011 (amended on 22 Apr. 2013) Other information: Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non- Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL- UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/Notices/View-UN-Notices- Individuals click here TAi.121 Name: 1: AZIZIRAHMAN 2: ABDUL AHAD 3: na 4: na ﻋﺰﯾﺰ اﻟﺮﺣﻤﺎن ﻋﺒﺪ اﻻﺣﺪ :(Name (original script Title: Mr Designation: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates DOB: 1972 POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: na Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: Afghanistan Passport no: na National identification no: Afghan national identification card (tazkira) number 44323 na Address: na Listed on: 25 Jan. -

A Case Study of Mahsud Tribe in South Waziristan Agency

RELIGIOUS MILITANCY AND TRIBAL TRANSFORMATION IN PAKISTAN: A CASE STUDY OF MAHSUD TRIBE IN SOUTH WAZIRISTAN AGENCY By MUHAMMAD IRFAN MAHSUD Ph.D. Scholar DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR (SESSION 2011 – 2012) RELIGIOUS MILITANCY AND TRIBAL TRANSFORMATION IN PAKISTAN: A CASE STUDY OF MAHSUD TRIBE IN SOUTH WAZIRISTAN AGENCY Thesis submitted to the Department of Political Science, University of Peshawar, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Award of the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE (December, 2018) DDeeddiiccaattiioonn I Dedicated this humble effort to my loving and the most caring Mother ABSTRACT The beginning of the 21st Century witnessed the rise of religious militancy in a more severe form exemplified by the traumatic incident of 9/11. While the phenomenon has troubled a significant part of the world, Pakistan is no exception in this regard. This research explores the role of the Mahsud tribe in the rise of the religious militancy in South Waziristan Agency (SWA). It further investigates the impact of militancy on the socio-cultural and political transformation of the Mahsuds. The study undertakes this research based on theories of religious militancy, borderland dynamics, ungoverned spaces and transformation. The findings suggest that the rise of religious militancy in SWA among the Mahsud tribes can be viewed as transformation of tribal revenge into an ideological conflict, triggered by flawed state policies. These policies included, disregard of local culture and traditions in perpetrating military intervention, banning of different militant groups from SWA and FATA simultaneously, which gave them the raison d‘etre to unite against the state and intensify violence and the issues resulting from poor state governance and control. -

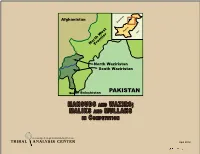

Mahsuds and Wazirs; Maliks and Mullahs in Competition

Afghanistan FGHANISTAN A PAKISTAN INIDA NorthFrontier West North Waziristan South Waziristan Balochistan PAKISTAN MAHSUDS AND WAZIRS; MALIKS AND MULLAHS IN C OMPETITION Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER April 2012 Mahsuds and Wazirs; Maliks and Mullahs in Competition M AHSUDS AND W AZIRS ; M ALIKS AND M ULLAHS IN C OMPETITION Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER About Tribal Analysis Center Tribal Analysis Center, 6610-M Mooretown Road, Box 159. Williamsburg, VA, 23188 Mahsuds and Wazirs; Maliks and Mullahs in Competition Mahsuds and Wazirs; Maliks and Mullahs in Competition No patchwork scheme—and all our present recent schemes...are mere patchwork— will settle the Waziristan problem. Not until the military steam-roller has passed over the country from end to end, will there be peace. But I do not want to be the person to start that machine. Lord Curzon, Britain’s viceroy of India The great drawback to progress in Afghanistan has been those men who, under the pretense of religion, have taught things which were entirely contrary to the teachings of Mohammad, and that, being the false leaders of the religion. The sooner they are got rid of, the better. Amir Abd al-Rahman (Kabul’s Iron Amir) The Pashtun tribes have individual “personality” characteristics and this is a factor more commonly seen within the independent tribes – and their sub-tribes – than in the large tribal “confederations” located in southern Afghanistan, the Durranis and Ghilzai tribes that have developed in- termarried leadership clans and have more in common than those unaffiliated, independent tribes. Isolated and surrounded by larger, and probably later arriving migrating Pashtun tribes and restricted to poorer land, the Mahsud tribe of the Wazirs evolved into a nearly unique “tribal culture.” For context, it is useful to review the overarching genealogy of the Pashtuns. -

1 TRIBE and STATE in WAZIRISTAN 1849-1883 Hugh Beattie Thesis

1 TRIBE AND STATE IN WAZIRISTAN 1849-1883 Hugh Beattie Thesis presented for PhD degree at the University of London School of Oriental and African Studies 1997 ProQuest Number: 10673067 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673067 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT The thesis begins by describing the socio-political and economic organisation of the tribes of Waziristan in the mid-nineteenth century, as well as aspects of their culture, attention being drawn to their egalitarian ethos and the importance of tarburwali, rivalry between patrilateral parallel cousins. It goes on to examine relations between the tribes and the British authorities in the first thirty years after the annexation of the Punjab. Along the south Waziristan border, Mahsud raiding was increasingly regarded as a problem, and the ways in which the British tried to deal with this are explored; in the 1870s indirect subsidies, and the imposition of ‘tribal responsibility’ are seen to have improved the position, but divisions within the tribe and the tensions created by the Second Anglo- Afghan War led to a tribal army burning Tank in 1879. -

Special Status of Tribal Areas (FATA): an Artificial Imperial Construct Bleeding Asia

Special Status of Tribal Areas (FATA): An Artificial Imperial Construct Bleeding Asia Sarfraz Khan* Introduction Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of Pakistan is a narrow belt stretching along the Pak-Afghan border, popularly known as the Durand Line, named after Sir Mortimor Durand, who surveyed and established this borderline between Afghanistan and British India in 1890-1894. It comprises seven agencies namely: Kurram, Khyber, North Waziristan, South Waziristan, Bajaur, Mohmand, and Orakzai along with six Frontier Regions (FRs): FR-Peshawar, FR-Kohat, FR.Bannu, FR.Lakki, FR. D.I.Khan, and FR.Tank. FATA accounts for 27220 km2 or 3.4% of Pakistan's land area. Either side of FATA Pashtun tribes reside in Afghanistan and Pakistan. According to the 1998 census the population of FATA was 3.138 million or 2.4% of Pakistan's total population, currently estimated approximately 3.5 million. Various Pashtun Muslim tribes inhabit FATA. A small number of religious minorities, Hindus and Sikhs, also inhabit some of the tribal agencies. The following are the tribes residing in FATA. In Khyber Agency: Afridi (Adamkhel, Akakhel, Kamarkhel, Kamberkhel, Kukikhel, Malik Dinkhel, Sipah, Zakhakhel), Shinwari (Ali Sherkhel), Mullagori (Ahmadkhel, Ismailkhel) and Shilmani (Shamsherkhel, Haleemzai, Kam Shilmani).1 In Kurram: Turi, Bangash, Sayed, Zaimusht, Mangal, Muqbil, Ali Sherzai, Massuzai, and Para Chamkani.2 In Bajaur: Salarzai branch of the Tarkalanri tribe (Ibrahim Khel, Bram Khel (Khan Khel) and Safi.3 In Mohmand: Musakhel, Tarakzai, Safi, Uthmankhel, and Haleemzai.4 In Orakzai: Aurakzai and Daulatzai. 5 In South Waziristan: Mahsud Wazir, and Dottani/ Suleman Khels.6 In North Waziristan: Dawar, Wazir, Saidgi and Gurbaz.7 In Frontier Regions: Ahmadzai, Uthmanzai, Shiranis, Ustrana, zarghunkhel, Akhorwal, Shirakai, Tor Chappar, Bostikhel, Jawaki, Hasan khel, Ashukhel, Pasani, Janakor, Tatta, Waraspun, and Dhana. -

Conflict Between India and Pakistan an Encyclopedia by Lyon Peter

Conflict between India and Pakistan Roots of Modern Conflict Conflict between India and Pakistan Peter Lyon Conflict in Afghanistan Ludwig W. Adamec and Frank A. Clements Conflict in the Former Yugoslavia John B. Allcock, Marko Milivojevic, and John J. Horton, editors Conflict in Korea James E. Hoare and Susan Pares Conflict in Northern Ireland Sydney Elliott and W. D. Flackes Conflict between India and Pakistan An Encyclopedia Peter Lyon Santa Barbara, California Denver, Colorado Oxford, England Copyright 2008 by ABC-CLIO, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lyon, Peter, 1934– Conflict between India and Pakistan : an encyclopedia / Peter Lyon. p. cm. — (Roots of modern conflict) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-57607-712-2 (hard copy : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-57607-713-9 (ebook) 1. India—Foreign relations—Pakistan—Encyclopedias. 2. Pakistan-Foreign relations— India—Encyclopedias. 3. India—Politics and government—Encyclopedias. 4. Pakistan— Politics and government—Encyclopedias. I. Title. DS450.P18L86 2008 954.04-dc22 2008022193 12 11 10 9 8 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Production Editor: Anna A. Moore Production Manager: Don Schmidt Media Editor: Jason Kniser Media Resources Manager: Caroline Price File Management Coordinator: Paula Gerard This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. -

Afghanistan INDIVIDUALS

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF FINANCIAL SANCTIONS TARGETS IN THE UK Last Updated:01/02/2021 Status: Asset Freeze Targets REGIME: Afghanistan INDIVIDUALS 1. Name 6: ABBASIN 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: n/a 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: --/--/1969. POB: Sheykhan village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan a.k.a: MAHSUD, Abdul Aziz Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):AFG0121 (UN Ref): TAi.155 (Further Identifiying Information):Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL-UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we- work/Notices/View-UN-Notices-Individuals click here. Listed on: 21/10/2011 Last Updated: 01/02/2021 Group ID: 12156. 2. Name 6: ABDUL AHAD 1: AZIZIRAHMAN 2: n/a 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. Title: Mr DOB: --/--/1972. POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Nationality: Afghan National Identification no: 44323 (Afghan) (tazkira) Position: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):AFG0094 (UN Ref): TAi.121 (Further Identifiying Information): Belongs to Hotak tribe. Review pursuant to Security Council resolution 1822 (2008) was concluded on 29 Jul. 2010. INTERPOL-UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/ Notices/View-UN-Notices-Individuals click here. Listed on: 23/02/2001 Last Updated: 01/02/2021 Group ID: 7055. -

Mainstreaming Pakistan's Federally Administered Tribal Areas

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 2301 Constitution Ave., NW • Washington, DC 20037 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Imtiaz Ali This report concerns the evolving status of Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas, a region that has been a hotbed of militancy and insurgency since 2002. Integrating this volatile region into mainstream Pakistan is vital to Pakistan’s peace and security and to overall regional stability. This report Mainstreaming Pakistan’s is based on in-country interviews with tribal and Pakistani government officials and research reports.The United States Institute of Peace (USIP) has been working in Pakistan on various peacebuilding initiatives. Federally Administered ABOUT THE AUTHOR Tribal Areas Imtiaz Ali is a writer and consultant whose work focuses on political, development, media, and security issues in Pakistan and adjoining areas. Formerly he reported for Pakistan-based Reform Initiatives and Roadblocks and other media organizations, including the Washington Post, BBC, and London’s Daily Telegraph. He was a Jennings Randolph Fellow at USIP in 2009–10. Summary • FATA—Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas—is widely considered one of the most volatile regions in the world. • Pakistan inherited FATA’s “special status” from the British colonial empire in 1947, and the region is still ruled under the British-era Frontier Crimes Regulations, which differs significantly from the legal system that applies to the rest of the country. • In the wake of 9/11, FATA became a haven for militants of all hues and thus of major © 2018 by the United States Institute of Peace. -

India & Sri Lanka 2

India & Sri Lanka 2 India & Sri Lanka 2 1 frontcover: no. 57 backcover: no. 17 Ex- tensive descriptions and images available on request. All offers are without engagement and subject to prior sale. All items in this list are complete and in good condition unless stated otherwise. Any item not agreeing with the description may be returned within one week after receipt. Prices are in eur (€). Postage and insurance are not included. VAT is charged at the standard rate to all EU customers. EU customers: please quote your VAT number when placing orders. Preferred mode of payment: in advance, wire transfer. Arrangements can be made for MasterCard and VisaCard. Ownership of goods does not pass to the purchaser until the price has been paid in full. General conditions of sale are those laid down in the ILAB Code of Usages and Customs, which can be viewed at: <http://www. ilab.org/eng/ilab/code.html> New customers are requested to provide references when ordering. ANTIL UARIAAT FOR?GE> 50 Y EARSUM @>@> Tuurdijk 16 Tuurdijk 16 3997 ms ‘t Goy 3997 ms ‘t Goy The Netherlands The Netherlands Phone: +31 (0)30 6011955 Phone: +31 (0)30 6011955 Fax: +31 (0)30 6011813 Fax: +31 (0)30 6011813 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.forumrarebooks.com Web: www.asherbooks.com India & Sri Lanka 2 1 frontcover: no. 57 backcover: no. 17 antiquariaat FORUM & ASHER Rare Books India & Sri Lanka 2 ‘t Goy 2020 Very rare anti-semitic Indian-Jewish Robinsonade with imaginary voyages from India to Portugal, Spain and the West and East Indies 1.