An Interpretive Analysis of George Antheil's Sonata for Trumpet And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

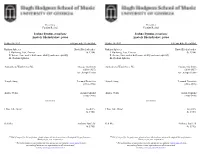

Joshua Bynum, Trombone Anatoly Sheludyakov, Piano Joshua Bynum

Presents a Presents a Faculty Recital Faculty Recital Joshua Bynum, trombone Joshua Bynum, trombone Anatoly Sheludyakov, piano Anatoly Sheludyakov, piano October 16, 2019 6:00 pm, Edge Recital Hall October 16, 2019 6:00 pm, Edge Recital Hall Radiant Spheres David Biedenbender Radiant Spheres David Biedenbender I. Fluttering, Fast, Precise (b. 1984) I. Fluttering, Fast, Precise (b. 1984) II. for me, time moves both more slowly and more quickly II. for me, time moves both more slowly and more quickly III. Radiant Spheres III. Radiant Spheres Someone to Watch Over Me George Gershwin Someone to Watch Over Me George Gershwin (1898-1937) (1898-1937) Arr. Joseph Turrin Arr. Joseph Turrin Simple Song Leonard Bernstein Simple Song Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) (1918-1990) Zion’s Walls Aaron Copland Zion’s Walls Aaron Copland (1900-1990) (1900-1990) -intermission- -intermission- I Was Like Wow! JacobTV I Was Like Wow! JacobTV (b. 1951) (b. 1951) Red Sky Anthony Barfield Red Sky Anthony Barfield (b. 1981) (b. 1981) **Out of respect for the performer, please silence all electronic devices throughout the performance. **Out of respect for the performer, please silence all electronic devices throughout the performance. Thank you for your cooperation. Thank you for your cooperation. ** For information on upcoming concerts, please see our website: music.uga.edu. Join ** For information on upcoming concerts, please see our website: music.uga.edu. Join our mailing list to receive information on all concerts and our mailing list to receive information on all concerts and recitals, music.uga.edu/enewsletter recitals, music.uga.edu/enewsletter Dr. Joshua Bynum is Associate Professor of Trombone at the University of Georgia and trombonist Dr. -

Recommended Solos and Ensembles Tenor Trombone Solos Sång Till

Recommended Solos and Ensembles Tenor Trombone Solos Sång till Lotta, Jan Sandström. Edition Tarrodi: Stockholm, Sweden, 1991. Trombone and piano. Requires modest range (F – g flat1), well-developed lyricism, and musicianship. There are two versions of this piece, this and another that is scored a minor third higher. Written dynamics are minimal. Although phrases and slurs are not indicated, it is a SONG…encourage legato tonguing! Stephan Schulz, bass trombonist of the Berlin Philharmonic, gives a great performance of this work on YouTube - http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mn8569oTBg8. A Winter’s Night, Kevin McKee, 2011. Available from the composer, www.kevinmckeemusic.com. Trombone and piano. Explores the relative minor of three keys, easy rhythms, keys, range (A – g1, ossia to b flat1). There is a fine recording of this work on his web site. Trombone Sonata, Gordon Jacob. Emerson Edition: Yorkshire, England, 1979. Trombone and piano. There are no real difficult rhythms or technical considerations in this work, which lasts about 7 minutes. There is tenor clef used throughout the second movement, and it switches between bass and tenor in the last movement. Range is F – b flat1. Recorded by Dr. Ron Babcock on his CD Trombone Treasures, and available at Hickey’s Music, www.hickeys.com. Divertimento, Edward Gregson. Chappell Music: London, 1968. Trombone and piano. Three movements, range is modest (G-g#1, ossia a1), bass clef throughout. Some mixed meter. Requires a mute, glissandi, and ad. lib. flutter tonguing. Recorded by Brett Baker on his CD The World of Trombone, volume 1, and can be purchased at http://www.brettbaker.co.uk/downloads/product=download-world-of-the- trombone-volume-1-brett-baker. -

Working List of Repertoire for Tenor Trombone Solo and Bass Trombone Solo by People of Color/People of the Global Majority (POC/PGM) and Women Composers

Working List of Repertoire for tenor trombone solo and bass trombone solo by People of Color/People of the Global Majority (POC/PGM) and Women Composers Working list v.2.4 ~ May 30, 2021 Prepared by Douglas Yeo, Guest Lecturer of Trombone Wheaton College Conservatory of Music Armerding Center for Music and the Arts www.wheaton.edu/conservatory 520 E. Kenilworth Avenue Wheaton, IL 60187 Email: [email protected] www.wheaton.edu/academics/faculty/douglas-yeo Works by People of Color/People of the Global Majority (POC/PGM) Composers: Tenor trombone • Amis, Kenneth Preludes 1–5 (with piano) www.kennethamis.com • Barfield, Anthony Meditations of Sound and Light (with piano) Red Sky (with piano/band) Soliloquy (with trombone quartet) www.anthonybarfield.com 1 • Baker, David Concert Piece (with string orchestra) - Lauren Keiser Publishing • Chavez, Carlos Concerto (with orchestra) - G. Schirmer • Coleridge-Taylor, Samuel (arr. Ralph Sauer) Gypsy Song & Dance (with piano) www.cherryclassics.com • DaCosta, Noel Four Preludes (with piano) Street Calls (unaccompanied) • Davis, Nathaniel Cleophas (arr. Aaron Hettinga) Oh Slip It Man (with piano) Mr. Trombonology (with piano) Miss Trombonism (with piano) Master Trombone (with piano) Trombone Francais (with piano) www.cherryclassics.com • John Duncan Concerto (with orchestra) Divertimento (with string quartet) Three Proclamations (with string quartet) library.umkc.edu/archival-collections/duncan • Hailstork, Adolphus Cunningham John Henry’s Big (Man vs. Machine) (with piano) - Theodore Presser • Hong, Sungji Feromenis pnois (unaccompanied) • Lam, Bun-Ching Three Easy Pieces (with electronics) • Lastres, Doris Magaly Ruiz Cuasi Danzón (with piano) Tres Piezas (with piano) • Ma, Youdao Fantasia on a Theme of Yada Meyrien (with piano/orchestra) - Jinan University Press (ISBN 9787566829207) • McCeary, Richard Deming Jr. -

Portable Digital Musical Instruments 2009 — 2010

PORTABLE DIGITAL MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS 2009 — 2010 music.yamaha.com/homekeyboard For details please contact: This document is printed with soy ink. Printed in Japan How far do you want What kind of music What are your Got rhythm? to go with your music? do you want to play? creative inclinations? Recommended Recommended Recommended Recommended Tyros3 PSR-OR700 NP-30 PSR-E323 EZ-200 DD-65 PSR-S910 PSR-S550B YPG series PSR-E223 PSR-S710 PSR-E413 Pages 4-7 Pages 8-11 Pages 12-13 Page 14 The sky's the limit. Our Digital Workstations are jam-packed If the piano is your thing, Yamaha has a range of compact We've got Digital Keyboards of all types to help players of every If drums and percussion are your strong forte, our Digital with advanced features, exceptionally realistic sounds and piano-oriented instruments that have amazingly realistic stripe achieve their full potential. Whether you're just starting Percussion unit gives you exceptionally dynamic and expressive performance functions that give you the power sound and wonderfully expressive playability–just like having out or are an experienced expert, our instrument lineup realistic sounds, letting you pound out your own beats–in to create, arrange and perform in any style or situation. a real piano in your house, with a fraction of the space. provides just what you need to get your creative juices flowing. live performance, in rehearsal or in recording. 2 3 Yamaha’s Premier Music Workstation – Unsurpassed Quality, Features and Performance Ultimate Realism Limitless Creative Potential Interactive -

The Lion's Roar

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ The Lion’s Roar A Thorne Student Publication Winter 2019 Still Free Elf Day Pg 3, Mania Album Review, Pg 3, Winter Concert Pg 4, The Arts Op Ed, Pg 4, Art Pg 5, Poetry Pg 6, Investigative Spotlight-Social Media Pg 8 Chinchillas Thorne Giving Back Kara Gallagher By: Kristen Gallagher Fortnite Allegedly Dying, Streamer Protests Notion By Liam Perez Since its initial release on September 26, 2017, the We all know the holidays are a great immensely popular online game time of year. Opening our presents known as Fortnite: Battle Royale on Christmas morning with beaming has captured the hearts, minds, smiles is always a joy, but what about those who aren’t as fortunate and wallets of over 200 million As you may know, the 7th-grade as us? players science classes have adorable, soft I am a member of Thorne’s peer worldwide(pcgamesn.com, 2018). chinchillas, but do you really know leaders, and we were invited to help However, speculation that Fortnite: Battle Royale’s time in anything about those fuzzy, out with a holiday toy drive that eye-watering creatures? Well, if you benefits Middletown residents. When the public eye is drawing to a don’t, you should definitely read this I heard of this volunteer close, or that it is ‘dead.’ This article. I will write about chinchilla opportunity, I was interested right leads to the questions of “is this fun facts, and caring for a pet away. Approximately twenty other true?” and “if it is, what’s next?”, chinchilla. Thorne students participated. -

John Cage's Entanglement with the Ideas Of

JOHN CAGE’S ENTANGLEMENT WITH THE IDEAS OF COOMARASWAMY Edward James Crooks PhD University of York Music July 2011 John Cage’s Entanglement with the Ideas of Coomaraswamy by Edward Crooks Abstract The American composer John Cage was famous for the expansiveness of his thought. In particular, his borrowings from ‘Oriental philosophy’ have directed the critical and popular reception of his works. But what is the reality of such claims? In the twenty years since his death, Cage scholars have started to discover the significant gap between Cage’s presentation of theories he claimed he borrowed from India, China, and Japan, and the presentation of the same theories in the sources he referenced. The present study delves into the circumstances and contexts of Cage’s Asian influences, specifically as related to Cage’s borrowings from the British-Ceylonese art historian and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In addition, Cage’s friendship with the Jungian mythologist Joseph Campbell is detailed, as are Cage’s borrowings from the theories of Jung. Particular attention is paid to the conservative ideology integral to the theories of all three thinkers. After a new analysis of the life and work of Coomaraswamy, the investigation focuses on the metaphysics of Coomaraswamy’s philosophy of art. The phrase ‘art is the imitation of nature in her manner of operation’ opens the doors to a wide- ranging exploration of the mimesis of intelligible and sensible forms. Comparing Coomaraswamy’s ‘Traditional’ idealism to Cage’s radical epistemological realism demonstrates the extent of the lack of congruity between the two thinkers. In a second chapter on Coomaraswamy, the extent of the differences between Cage and Coomaraswamy are revealed through investigating their differing approaches to rasa , the Renaissance, tradition, ‘art and life’, and museums. -

FRENCH CONNECTIONS with Avery Gagliano, Piano

FRENCH CONNECTIONS with Avery Gagliano, piano February 13, 2021 | 7:30 PM Welcome to OMP's Virtual Concert Hall! Bonjour et bienvenue! Thank you to our loyal donors and season subscribers for your continued support, and a warm welcome to those who are joining us in our "Virtual Concert Hall" for the first time. Your contributions have made it possible for OMP to present our third virtual chamber orchestra performance in HD audio and video! We hope you enjoy this programme musical français featuring First Prize and Best Concerto Prize winner of the 2020 10th National Chopin Piano Competition Avery Gagliano! THANK YOU TO THESE GENEROUS GRANTING ORGANIZATIONS: Get the PremiumExperience! Level A Subscription Seat Access to Virtual Premium Special Concerts and additional OMP content or concerts. Receive "Kelly's Recommendation" in headphones: Bose® SoundLink around-ear headphones II with contactless shipping Select a personally autographed CD or DVD of "A Virtual Recital", featuring 2015 Young Soloist Competition Winner John Fawcett, violin and Kelly Kuo, piano. Complimentary, contactless wine delivery upon virtual reception advanced reservation Current 2020-21 Subscribers can use the amount of their tickets as a credit toward their purchase of an OMP Premium Experience Package! Give the gift of with OMP and Bose at oregonmomzaurstipclayers.org/tickets Orchestra Kelly Kuo, Artistic Director & Conductor VIOLIN Jenny Estrin, acting concertmaster Yvonne Hsueh, principal 2nd violin Stephen Chong Della Davies Sponsored by Nancy & Brian Davies Julia Frantz Sponsored by James & Paula Salerno Nathan Lowman Claudia Miller Sponsored by Jeffrey Morey & Gail Harris Sophie Therrell Sponsored by W. Mark & Anne Dean Alwyn Wright* VIOLA Arnaud Ghillebaert principal viola Lauren Elledge Kimberly Uwate* CELLO Dale Bradley acting principal cello Sponsored by Larissa Ennis & Lindsay Braun Eric Alterman Noah Seitz BASS Nicholas Burton, principal bass HARPSICHORD/PIANO Thank you to our additional musician sponsors: John Jantzi, Theodore W. -

Lost Generation.” Two Recent Del Sol Quartet Recordings Focus on Their Little-Known Chamber Music

American Masterpieces Chamber Music Americans in Paris Like Hemingway and Fitzgerald, composers Marc Blitzstein and George Antheil were a part of the 1920s “Lost Generation.” Two recent Del Sol Quartet recordings focus on their little-known chamber music. by James M. Keller “ ou are all a lost generation,” Generation” conveyed the idea that these Gertrude Stein remarked to literary Americans abroad were left to chart Y Ernest Hemingway, who then their own paths without the compasses of turned around and used that sentence as the preceding generation, since the values an epigraph to close his 1926 novel The and expectations that had shaped their Sun Also Rises. upbringings—the rules that governed Later, in his posthumously published their lives—had changed fundamentally memoir, A Moveable Feast, Hemingway through the Great War’s horror. elaborated that Stein had not invented the We are less likely to find the term Lost locution “Lost Generation” but rather merely Generation applied to the American expa- adopted it after a garage proprietor had triate composers of that decade. In fact, used the words to scold an employee who young composers were also very likely to showed insufficient enthusiasm in repairing flee the United States for Europe during the ignition in her Model-T Ford. Not the 1920s and early ’30s, to the extent that withstanding its grease-stained origins, one-way tickets on transatlantic steamers the phrase lingered in the language as a seem to feature in the biographies of most descriptor for the brigade of American art- American composers who came of age at ists who spent time in Europe during the that moment. -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

An Examination of Jerry Goldsmith's

THE FORBIDDEN ZONE, ESCAPING EARTH AND TONALITY: AN EXAMINATION OF JERRY GOLDSMITH’S TWELVE-TONE SCORE FOR PLANET OF THE APES VINCENT GASSI A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO MAY 2019 © VINCENT GASSI, 2019 ii ABSTRACT Jerry GoldsMith’s twelve-tone score for Planet of the Apes (1968) stands apart in Hollywood’s long history of tonal scores. His extensive use of tone rows and permutations throughout the entire score helped to create the diegetic world so integral to the success of the filM. GoldsMith’s formative years prior to 1967–his training and day to day experience of writing Music for draMatic situations—were critical factors in preparing hiM to meet this challenge. A review of the research on music and eMotion, together with an analysis of GoldsMith’s methods, shows how, in 1967, he was able to create an expressive twelve-tone score which supported the narrative of the filM. The score for Planet of the Apes Marks a pivotal moment in an industry with a long-standing bias toward modernist music. iii For Mary and Bruno Gassi. The gift of music you passed on was a game-changer. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Heartfelt thanks and much love go to my aMazing wife Alison and our awesome children, Daniela, Vince Jr., and Shira, without whose unending patience and encourageMent I could do nothing. I aM ever grateful to my brother Carmen Gassi, not only for introducing me to the music of Jerry GoldsMith, but also for our ongoing conversations over the years about filM music, composers, and composition in general; I’ve learned so much. -

Mengjiao Yan Phd Thesis.Pdf

The University of Sheffield Stravinsky’s piano works from three distinct periods: aspects of performance and latitude of interpretation Mengjiao Yan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music The University of Sheffield Jessop Building, Sheffield, S3 7RD, UK September 2019 1 Abstract This research project focuses on the piano works of Igor Stravinsky. This performance- orientated approach and analysis aims to offer useful insights into how to interpret and make informed decisions regarding his piano music. The focus is on three piano works: Piano Sonata in F-Sharp Minor (1904), Serenade in A (1925), Movements for Piano and Orchestra (1958–59). It identifies the key factors which influenced his works and his compositional process. The aims are to provide an informed approach to his piano works, which are generally considered difficult and challenging pieces to perform convincingly. In this way, it is possible to offer insights which could help performers fully understand his works and apply this knowledge to performance. The study also explores aspects of latitude in interpreting his works and how to approach the notated scores. The methods used in the study include document analysis, analysis of music score, recording and interview data. The interview participants were carefully selected professional pianists who are considered experts in their field and, therefore, authorities on Stravinsky's piano works. The findings of the results reveal the complex and multi-faceted nature of Stravinsky’s piano music. The research highlights both the intrinsic differences in the stylistic features of the three pieces, as well as similarities and differences regarding Stravinsky’s compositional approach. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1983, Tanglewood

. ^ 5^^ mar9 E^ ^"l^Hifi imSSii^*^^ ' •H-.-..-. 1 '1 i 1^ «^^«i»^^^m^ ^ "^^^^^. Llii:^^^ %^?W. ^ltm-''^4 j;4W»HH|K,tf.''if :**.. .^l^^- ^-?«^g?^5?,^^^^ _ '^ ** '.' *^*'^V^ - 1 jV^^ii 5 '|>5|. * .««8W!g^4sMi^^ -\.J1L Majestic pine lined drives, rambling elegant mfenor h^^, meandering lawns and gardens, velvet green mountain *4%ta! canoeing ponds and Laurel Lake. Two -hundred acres of the and present tastefully mingled. Afulfillment of every vacation delight . executive conference fancy . and elegant home dream. A choice for a day ... a month . a year. Savor the cuisine, entertainment in the lounges, horseback, sleigh, and carriage rides, health spa, tennis, swimming, fishing, skiing, golf The great estate tradition is at your fingertips, and we await you graciously with information on how to be part of the Foxhollow experience. Foxhollow . an tver growing select family. Offerings in: Vacation Homes, Time- Shared Villas, Conference Center. Route 7, Lenox, Massachusetts 01240 413-637-2000 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Sir Colin Davis, Principal Guest Conductor Joseph Silverstein, Assistant Conductor One Hundred and Second Season, 1982-83 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Abram T. Collier, Chairman Nelson J. Darling, Jr., President Leo L. Beranek, Vice-President George H. Kidder, Vice-President Mrs. Harris Fahnestock, Vice-President Sidney Stoneman, Vice-President Roderick M. MacDougall, Treasurer John Ex Rodgers, Assistant Treasurer Vernon R. Alden Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick William J. Poorvu J. P. Barger Mrs. John L. Grandin Irving W. Rabb Mrs. John M. Bradley David G. Mugar Mrs. George R. Rowland Mrs. Norman L. Cahners Albert L. Nickerson Mrs. George Lee Sargent George H.A.