“Formal Renditions”: Revisiting the Baraka-Ellison Debate, an Essay By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry Howard Rambsy II The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor First paperback edition 2013 Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2011 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 5432 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rambsy, Howard. The black arts enterprise and the production of African American poetry / Howard Rambsy, II. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11733-8 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Poetry—Publishing—United States—History—20th century. 3. African Americans—Intellectual life—20th century. 4. African Americans in literature. I. Title. PS310.N4R35 2011 811'.509896073—dc22 2010043190 ISBN 978-0-472-03568-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12005-5 (e-book) Cover illustrations: photos of writers (1) Haki Madhubuti and (2) Askia M. Touré, Mari Evans, and Kalamu ya Salaam by Eugene B. Redmond; other images from Shutterstock.com: jazz player by Ian Tragen; African mask by Michael Wesemann; fist by Brad Collett. -

Blues Tribute Poems in Twentieth- and Twenty-First Century American Poetry Emily Rutter

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2014 Constructions of the Muse: Blues Tribute Poems in Twentieth- and Twenty-First Century American Poetry Emily Rutter Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Rutter, E. (2014). Constructions of the Muse: Blues Tribute Poems in Twentieth- and Twenty-First Century American Poetry (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1136 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE MUSE: BLUES TRIBUTE POEMS IN TWENTIETH- AND TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Emily Ruth Rutter March 2014 Copyright by Emily Ruth Rutter 2014 ii CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE MUSE: BLUES TRIBUTE POEMS IN TWENTIETH- AND TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY By Emily Ruth Rutter Approved March 12, 2014 ________________________________ ________________________________ Linda A. Kinnahan Kathy L. Glass Professor of English Associate Professor of English (Committee Chair) (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ Laura Engel Thomas P. Kinnahan Associate Professor of English Assistant Professor of English (Committee Member) (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ James Swindal Greg Barnhisel Dean, McAnulty College of Liberal Arts Chair, English Department Professor of Philosophy Associate Professor of English iii ABSTRACT CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE MUSE: BLUES TRIBUTE POEMS IN TWENTIETH- AND TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY By Emily Ruth Rutter March 2014 Dissertation supervised by Professor Linda A. -

Literary African Heritage, Primarily in Response to an Omnipresent

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 058 182 TE 002 438 AUTHOR Schultz, Elizabeth TITLE The Blues in Black Literature. PUB DATE Feb 71 NOTE 5p. JOURNAL CIT Kansas English; v56 n3 p19-23 February 1971 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS *American Literature; Composition (Literary); *Cultural Factors; *Language Usage; *Literary Criticism; *Negro Literature; Poetry; Social Dialects ABSTRACT The literature of black America repeatedly reflects a native rootlessness and its creators' yearning for a home. The black writer settles his work in an ethos, which has evolved from an older African heritage, primarily in response to an omnipresent white society. In this document, one of these ethnic expressions--the blues--is examined as a means of exploring American Negro literature in general. The blues form a body of significant poems and, transmuted, they become the symbolic basis of such complex works as Richard Wright's "Black Boy" and Ralph Ellison's "Invisible Man." In formal terms, the blues are typically a 12 bar, three line stanza--the first two lines repeated, but linked in content and rhyme with the third. (CK) The Blues in Black Literature ELIZABETH SCHULTZ Kansas University American literature has always reflected the American's restlessness and rootlessness. Ishmael goes off to the South Seas. Huck Finn takes a raft down the Mississippi. Christopher Newman heads for Europe. Yet American writers repeatedly ground their works in a particular locale. Hawthorne sticks close to Salem, Faulkner confines himself to his particular postage-stamp, Yoknapataw- pha County, Saul Bellow locates the majority of his works in large urban cen- ters. -

The Influence of Louis Armstrong on the Harlem Renaissance 1923-1930

ABSTRACT HUMANITIES DECUIR, MICHAEL B.A. SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY AT NEW ORLEANS, 1987 M.A. THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY, 1989 THE INFLUENCE OF LOUIS ARMSTRONG ON THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE 1923–1930 Committee Chair: Timothy Askew, Ph.D. Dissertation dated August 2018 This research explores Louis Armstrong’s artistic choices and their impact directly and indirectly on the African-American literary, visual and performing arts between 1923 and 1930 during the period known as the Harlem Renaissance. This research uses analyses of musical transcriptions and examples of the period’s literary and visual arts to verify the significance of Armstrong’s influence(s). This research also analyzes the early nineteenth century West-African musical practices evident in Congo Square that were present in the traditional jazz and cultural behaviors that Armstrong heard and experienced growing up in New Orleans. Additionally, through a discourse analysis approach, this research examines the impact of Armstrong’s art on the philosophical debate regarding the purpose of the period’s art. Specifically, W.E.B. Du i Bois’s desire for the period’s art to be used as propaganda and Alain Locke’s admonitions that period African-American artists not produce works with the plight of blacks in America as the sole theme. ii THE INFLUENCE OF LOUIS ARMSTRONG ON THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE 1923–1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CLARK ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARTS IN HUMANITIES BY MICHAEL DECUIR DEPARTMENT OF HUMANITIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA AUGUST 2018 © 2018 MICHAEL DECUIR All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My greatest debt of gratitude goes to my first music teacher, my mother Laura. -

From Within the Frame: Storytelling in African-American Fiction

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1998 From within the frame: Storytelling in African-American fiction Bertram Duane Ashe College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Ashe, Bertram Duane, "From within the frame: Storytelling in African-American fiction" (1998). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623921. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-s19x-y607 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USRRS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. U M I films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter free, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality o f this reproduction is dependent upon the quality o f the copy submitted* Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send U M I a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

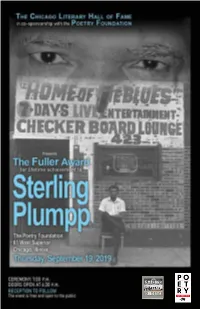

Download Program

Tonight’s Program Stephen Young .....................................Welcome to the Poetry Foundation Randy Albers ................................................................... About the Fuller Award Ronne Hartfield ...............Signs of Life: Regarding Sterling Plumpp, Poet Reginald Gibbons ................................................................................ Poetic Voice Ginger Mance ...............................................Reading, “The Moonsong Sings” Abdul Alkalimat ................................................................Black Experience Poet Duriel E. Harris ......................................................In Callings’ Unquiet Borders Billy Branch .....................................................................The Blues and the Muse Tyehimba Jess ................................................................................................Respect Donald G. Evans ...................................................Presenting the Fuller Award for lifetime achievement Sterling Plumpp .................................................................... Acceptance Speech Program cover by Denise Billups “I was here permanently—I was here to live—by 1962. And the thing that struck me about blues singers, that I had never really articulated before, was that they sang with the same kind of pain [as] my uncles, my grandfathers, and the men folks I knew on the farms—that that was where they had come from, that they had not done anything to change the language; they had found a way of making art out -

" African Blues": the Sound and History of a Transatlantic Discourse

“African Blues”: The Sound and History of a Transatlantic Discourse A thesis submitted to The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music by Saul Meyerson-Knox BA, Guilford College, 2007 Committee Chair: Stefan Fiol, PhD Abstract This thesis explores the musical style known as “African Blues” in terms of its historical and social implications. Contemporary West African music sold as “African Blues” has become commercially successful in the West in part because of popular notions of the connection between American blues and African music. Significant scholarship has attempted to cite the “home of the blues” in Africa and prove the retention of African music traits in the blues; however much of this is based on problematic assumptions and preconceived notions of “the blues.” Since the earliest studies, “the blues” has been grounded in discourse of racial difference, authenticity, and origin-seeking, which have characterized the blues narrative and the conceptualization of the music. This study shows how the bi-directional movement of music has been used by scholars, record companies, and performing artist for different reasons without full consideration of its historical implications. i Copyright © 2013 by Saul Meyerson-Knox All rights reserved. ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my utmost gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Stefan Fiol for his support, inspiration, and enthusiasm. Dr. Fiol introduced me to the field of ethnomusicology, and his courses and performance labs have changed the way I think about music. -

Black History Month

HERMANN MEMORIAL LIBRARY -- SULLIVAN COUNTY COMMUNITY COLLEGE BLACK HISTORY MONTH SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF TITLES FROM OUR PRINT COLLECTIONS AND FROM EBRARY The following bibliography is a sampling from our collections of the broad range of work by and about African Americans reflecting their immeasurable importance in our history and culture. It includes reference books, and circulating books.. The bibliography is not a checklist of books on display in the exhibition, but each is intended to complement the other. Many more books than are listed here can be found in our Sullivan Catalog. Full-text articles in magazines, journals and newspapers can be accessed from our Subscription Periodical Databases. A librarian will be glad to show you how to search these tools. Our own paper periodical collections include many titles of especial relevance to Black studies, as well as general interest magazines which cover Black issues. See our separately issued Periodical List. Books by and about Martin Luther King have been published in another bibliography available in this library. Please refer to that bibliography to research this topic. I. REFERENCE BOOKS African American lives. Edited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004) R 920.9301451/AF83G African American writers. Valerie Smith, editor. Rev. ed. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2000) R 810.9/AF83S Africana: the encyclopedia of the African and African American experience. (New York: Basic Civitas Books, 1999) R 301.451/AF83A Afro-American poetry and drama, 1760-1975: a guide to information sources. (Detroit: Gale, 1979) R 810.90/AF85. -

Charles Waddell Chesnutt: Aspiration and Perception

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s}". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Diplomarbeit Final Version 12.3.2011

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „The Representation of Blues and Jazz Musicians in American Fiction from the 1930s to the 1980s“ Verfasserin Elisabeth Strauss angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2011. Studienkennzahlt lt. Studienblatt:. A 343 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Anglistik und Amerikanistik Betreuer: Univ. -Prof. Dr. Waldemar Zacharasiewicz Hinweis Diese Diplomarbeit hat nachgewiesen, dass die betreffende Kandidatin befähigt ist, wissenschaftliche Themen selbstständig sowie inhaltlich und methodisch vertretbar zu bearbeiten. Da die Korrekturen der/des Beurteilenden nicht eingetragen sind und das Gutachten nicht beiliegt, ist daher nicht erkenntlich, mit welcher Note diese Arbeit abgeschlossen wurde. Das Spektrum reicht von sehr gut bis genügend. Es wird gebeten, diesen Hinweis bei der Lektüre zu beachten. Hiermit bestätige ich diese Arbeit nach bestem Wissen und Gewissen selbständig verfasst und die Regeln der guten wissenschaftlichen Praxis eingehalten zu haben. Table of Contents 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 2 The Blues ............................................................................................................................. 3 2.1 The economic situation ................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Discrimination and segregation ..................................................................................... -

All Blues: a Study of African-American Resistance Poetry. Anthony Jerome Bolden Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1998 All Blues: A Study of African-American Resistance Poetry. Anthony Jerome Bolden Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Bolden, Anthony Jerome, "All Blues: A Study of African-American Resistance Poetry." (1998). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6720. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6720 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Spiritual, Blues, and Jazz People in Mrican American Fiction: Living in Paradox / A

Spiritual, Blues, a;nd Jazz People ifl; African American Fiction Living in Paradox A. Yemisi Jimoh THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE PRESS / KNOXVILLE Copyright © 2002 by The University of Tennessee Press / Knoxville. All Rights Reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. First Edition. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jimoh, A. Yemisi Spiritual, blues, and jazz people in Mrican American fiction: living in paradox / A. YemisiJimoh.-lst ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-57233-172-0 (cl.: alk. paper) 1. American fiction-Mrican American authors-History and criticism. 2. Mrican American musicians in literature. 3. Musical fiction-History and criticism. 4. Spirituals (Songs) in literature. 5. Mrican Americans in literature. 6. Jazz musicians in literature. 7. Blues (Music) in literature. 8. Music and literature. 9. Music in literature. 10. Jazz in literature. 1. Title. PS374.N4 JS6 2002 813.009'896073-dc21 2001004286 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii INTRODUCTION We'll Understand It Better By and By one MUDDY WATERS Music in African American Fiction 22 ~wo STORMY BLUES From the Folk into Literary Form 41 ~ hree THESE (BLACKNESS OF BLACKNESS) BLUES 91 four DIZZY ATMOSPHERE 155 five JAZZ ME BLUES Reading Music in James Baldwin's "Sonny's Blues" 202 CONCLUSION Toward a Stopping Place 216 APPENDIX Allusions and References to Musicians and Music in the Narratives 219 NOTES 223 WORKS CITED AND CONSULTED 245 A SELECTED LIST OF BIOGRAPHIES AND AUTOBIOGRAPHIES OF MUSICIANS 263 INDEX 267 Contexts rom ancient times music and storytelling have been closely tied among Fthe peoples of oral cultures worldwide.