Final Report - New Top Level Domains of National Importance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate in Svalbard 2100

M-1242 | 2018 Climate in Svalbard 2100 – a knowledge base for climate adaptation NCCS report no. 1/2019 Photo: Ketil Isaksen, MET Norway Editors I.Hanssen-Bauer, E.J.Førland, H.Hisdal, S.Mayer, A.B.Sandø, A.Sorteberg CLIMATE IN SVALBARD 2100 CLIMATE IN SVALBARD 2100 Commissioned by Title: Date Climate in Svalbard 2100 January 2019 – a knowledge base for climate adaptation ISSN nr. Rapport nr. 2387-3027 1/2019 Authors Classification Editors: I.Hanssen-Bauer1,12, E.J.Førland1,12, H.Hisdal2,12, Free S.Mayer3,12,13, A.B.Sandø5,13, A.Sorteberg4,13 Clients Authors: M.Adakudlu3,13, J.Andresen2, J.Bakke4,13, S.Beldring2,12, R.Benestad1, W. Bilt4,13, J.Bogen2, C.Borstad6, Norwegian Environment Agency (Miljødirektoratet) K.Breili9, Ø.Breivik1,4, K.Y.Børsheim5,13, H.H.Christiansen6, A.Dobler1, R.Engeset2, R.Frauenfelder7, S.Gerland10, H.M.Gjelten1, J.Gundersen2, K.Isaksen1,12, C.Jaedicke7, H.Kierulf9, J.Kohler10, H.Li2,12, J.Lutz1,12, K.Melvold2,12, Client’s reference 1,12 4,6 2,12 5,8,13 A.Mezghani , F.Nilsen , I.B.Nilsen , J.E.Ø.Nilsen , http://www.miljodirektoratet.no/M1242 O. Pavlova10, O.Ravndal9, B.Risebrobakken3,13, T.Saloranta2, S.Sandven6,8,13, T.V.Schuler6,11, M.J.R.Simpson9, M.Skogen5,13, L.H.Smedsrud4,6,13, M.Sund2, D. Vikhamar-Schuler1,2,12, S.Westermann11, W.K.Wong2,12 Affiliations: See Acknowledgements! Abstract The Norwegian Centre for Climate Services (NCCS) is collaboration between the Norwegian Meteorological In- This report was commissioned by the Norwegian Environment Agency in order to provide basic information for use stitute, the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate, Norwegian Research Centre and the Bjerknes in climate change adaptation in Svalbard. -

'.Com,' Names for Antarctica, Urdu and More 17 June 2011, by ANICK JESDANUN , AP Technology Writer

Beyond '.com,' names for Antarctica, Urdu and more 17 June 2011, By ANICK JESDANUN , AP Technology Writer (AP) -- Unless you're a Luddite, you're bound to the system from that round, including ".xxx." know of ".com," the Internet's most common address suffix. Meanwhile, ICANN approved ".ps" for the Palestinian territories (in 2000) and ".eu" for the You've also probably heard of ".gov," for U.S. European Union (in 2005). That's because those government sites, and ".edu," for educational two were on a country-code list kept by the institutions. International Organization for Standards, which in turn takes information from the United Nations. Did you know Antarctica has its own suffix, too? It's More recently, ICANN approved country names in ".aq." languages other than English - so India has ones for Hindi, Urdu and five others. The aviation industry has ".aero" and porn sites have ".xxx." There's ".asia" for the continent, plus An expansion plan before ICANN on Monday would suffixes for individual countries such as Thailand streamline procedures for creating names and (".th") and South Korea (".kr"). Thailand and Korea allow for an endless number. also have addresses in Thai and Korean. Just as names get added, names can disappear. There are currently 310 domain name suffixes - the Yugoslavia's ".yu" is gone, as is East Germany's ".com" part of Web and email addresses. Now, the ".dd." There's no longer an ".um" for the U.S. "minor organization that oversees the system is poised to outlying islands," which include the Midway Islands. accept hundreds or thousands more. -

Key-Site Monitoring in Norway 2018, Including Svalbard and Jan Mayen

Short Report 1-2019 Key-site monitoring in Norway 2018, including Svalbard and Jan Mayen Tycho Anker-Nilssen, Rob Barrett, Børge Moe, Tone K. Reiertsen, Geir H. Systad, Jan Ove Bustnes, Signe Christensen-Dalsgaard, Sébastien Descamps, Kjell-Einar Erikstad, Arne Follestad, Sveinn Are Hanssen, Magdalene Langset, Svein-Håkon Lorentsen, Erlend Lorentzen, Hallvard Strøm, © SEAPOP 2019 SEAPOP Short Report 1-2019 Key-site monitoring in Norway 2018, including Svalbard and Jan Mayen Breeding success The 2018 breeding season was, overall, not good for Norwegian seabirds (Table 1a) with a third of the populations having a poor breeding success, as was the case in 2017. Fortunately, several populations did do well (38% compared to 34% in 2017). When comparing pelagic and coastal populations, the former were more successful (43% good, 22% poor) than the coastal (33% good, 33% poor). Among the pelagic species, northern gannets and razorbills fared best with a good breeding success recorded in two out of two and three of four populations respectively. Common guillemots also did well with five of eight populations having good breeding success. The three puffin colonies monitored in the Barents Sea produced many chicks while at Røst breeding success was poor for the 12th year in a row. At the two other colonies in the Norwegian Sea, it was moderate. Little auks on Bjørnøya did well, but only moderately so on Spitsbergen. The fulmar’s success on Jan Mayen was good, but poor on Røst and Sklinna. Brünnich’s guillemots had a poor breeding season on Jan Mayen, a good one on Bjørnøya and a moderate one on Spitsbergen. -

THE Kingdom OF

THE KINGDOM OF BY Clifford J. Mugnier, CP, CMS, FASPRS The Grids & Datums column has completed an exploration of every country on the Earth. For those who did not get to enjoy this world tour the first time,PE&RS is reprinting prior articles from the column. This month’s article on the Kingdom of Norway was originally printed in 1999 but contains updates to their coordinate system since then. orway was settled in the Middle Stone Age (circa 7000 B.C.), and by the 9th century NA.D., the Norse expeditions began which colonized the islands off Scotland, Ireland, Ice- land, and Greenland. Trondheim was the Nor- wegian capital until 1380. Kristiania, founded in 1050, became the capital in the 14th century and was renamed Oslo in 1924. The Kingdom occupies the western part of the Scandinavian Peninsula. It is bounded on the west by the Atlantic Ocean, on the north by the Arctic Ocean, on the north east by Russia and Finland, on the east by Sweden, and on the south by the Skagerrak and Denmark. Because of the numerous fjords and small coastal sured on Lake Storsren using wooden sur-vey bars. By 1784, a islands, the Kingdom has one of the longest coast- triangulation arc was surveyed between Kongsvinger and Ver- lines in the world. Norway claims the islands of dal. Additional triangulation work continued, and the survey was adjusted in 1810. The geographical position of Bergen was Svalbard and Jan Mayen in the Norwegian Sea. compared to another determination from a triangulation arc The earliest modern map of Nor-way was the map of Scandi- from Lindesnes. -

Glaciers in Svalbard: Mass Balance, Runoff and Freshwater Flux

Glaciers in Svalbard: mass balance, runoff and freshwater fl ux Jon Ove Hagen, Jack Kohler, Kjetil Melvold & Jan-Gunnar Winther Gain or loss of the freshwater stored in Svalbard glaciers has both global implications for sea level and, on a more local scale, impacts upon the hydrology of rivers and the freshwater fl ux to fjords. This paper gives an overview of the potential runoff from the Svalbard glaciers. The fresh- water fl ux from basins of different scales is quantifi ed. In small basins (A < 10 km2), the extra runoff due to the negative mass balance of the gla- ciers is related to the proportion of glacier cover and can at present yield more than 20 % higher runoff than if the glaciers were in equilibrium with the present climate. This does not apply generally to the ice masses of Svalbard, which are mostly much closer to being in balance. The total surface runoff from Svalbard glaciers due to melting of snow and ice is roughly 25 ± 5 km3 a-1, which corresponds to a specifi c runoff of 680 ± 140 mm a-1, only slightly more than the annual snow accumulation. Calving of icebergs from Svalbard glaciers currently contributes signifi cantly to the freshwater fl ux and is estimated to be 4 ± 1 km3 a-1 or about 110 mm a-1. J. O. Hagen & K. Melvold, Dept. of Physical Geography, University of Oslo, Box 1042 Blindern, NO-0316 Oslo, Norway, j.o.m.hagen@geografi .uio.no; J. Kohler & J.-G. Winther, Norwegian Polar Institute, Polar Environmental Centre, NO-9296 Tromsø, Norway. -

Svalbard and Jan Mayen (Norway)

Provided by NaTHNaC https://travelhealthpro.org.uk Printed:25 Sep 2021 Svalbard And Jan Mayen (Norway) Capital City : "Longyearbyen" Official Language: "Norwegian, Russian" Monetary Unit: "Norwegian krone (NOK)" General Information See also: Norway The information on these pages should be used to research health risks and to inform the pre-travel consultation. Due to COVID-19, travel advice is subject to rapid change. Countries may change entry requirements and close their borders at very short notice. Travellers must ensure they check current Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) travel advice in addition to the FCDO specific country page (where available) which provides additional information on travel restrictions and entry requirements in addition to safety and security advice. Travellers should ideally arrange an appointment with their health professional at least four to six weeks before travel. However, even if time is short, an appointment is still worthwhile. This appointment provides an opportunity to assess health risks taking into account a number of factors including destination, medical history, and planned activities. For those with pre-existing health problems, an earlier appointment is recommended. All travellers should ensure they have adequate travel health insurance. If visiting European Union (EU) countries carry an European Health Insurance Card (EHIC)ora Global Health Insurance Card (GHIC) as this will allow access to state-provided healthcare in some countries, at a reduced cost, or sometimes for free. The EHIC or GHIC, however, is not an alternative to travel insurance. Check the GOV.UK website for guidance. A list of useful resources including advice on how to reduce the risk of certain health problems is available below. -

Scientific Activities on Spitsbergen in the Light of the International Legal Status of the Archipelago

POLISH POLAR RESEARCH 16 1-2 13-35 1995 Jacek MACHOWSKI Institute of International Law Warsaw University Krakowskie Przedmieście 1 00-068 Warszawa, POLAND Scientific activities on Spitsbergen in the light of the international legal status of the archipelago ABSTRACT: In this article, Svalbard was presented as place and object of intensive scientific research, carried on under the rule of the 1920 Spitsbergen Treaty, which has transformed the archipelago into a unique political and legal entity, having no counterpart anywhere else in the world. Scientific activities in Svalbard are carried out within an uncommon legal framework, shaped by a body of instruments both of international law and domestic laws of Norway, as well as other countries concerned, while the Spitsbergen Treaty, in despite of its advanced age of 75 years, still remains a workable international instrument, fundamental to the maintenance of law and order within the whole Arctic region. In 1995 two important for Svalbard anniversaries were noted: on 9 February, 75 years of the signing of the Spitsbegren Treaty and on 14 August, 70 years of the Norwegian rule over the archipelago. Key words: Arctic, Spitsbergen, scientific cooperation, law and politics. Introduction The recent missile incident in the Arctic1 and the Russian-Norwegian controversy accompanying it, have turned for a while the attention of world public opinion to the status of Spitsbergen (Svalbard)2 and the conditions of scientific investigations in the archipelago. 1 The Times, 26 January, 1995, p. 12. On 25 January 1995 the world public opinion was alarmed by the news that a Norwegian missile has violated the airspace of Russia, putting its defence on alert. -

Svalbard 2015–2016 Meld

Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security Published by: Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security Public institutions may order additional copies from: Norwegian Government Security and Service Organisation E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.publikasjoner.dep.no KET T Meld. St. 32 (2015–2016) Report to the Storting (white paper) Telephone: + 47 222 40 000 ER RY M K Ø K J E L R I I Photo: Longyearbyen, Tommy Dahl Markussen M 0 Print: 07 PrintMedia AS 7 9 7 P 3 R 0 I 1 08/2017 – Impression 1000 N 4 TM 0 EDIA – 2 Svalbard 2015–2016 Meld. St. 32 (2015–2016) Report to the Storting (white paper) 1 Svalbard Meld. St. 32 (2015–2016) Report to the Storting (white paper) Svalbard Translation from Norwegian. For information only. Table of Contents 1 Summary ........................................ 5 6Longyearbyen .............................. 39 1.1 A predictable Svalbard policy ........ 5 6.1 Introduction .................................... 39 1.2 Contents of each chapter ............... 6 6.2 Areas for further development ..... 40 1.3 Full overview of measures ............. 8 6.2.1 Tourism: Longyearbyen and surrounding areas .......................... 41 2Background .................................. 11 6.2.2 Relocation of public-sector jobs .... 43 2.1 Introduction .................................... 11 6.2.3 Port development ........................... 44 2.2 Main policy objectives for Svalbard 11 6.2.4 Svalbard Science Centre ............... 45 2.3 Svalbard in general ........................ 12 6.2.5 Land development in Longyearbyen ................................ 46 3 Framework under international 6.2.6 Energy supply ................................ 46 law .................................................... 17 6.2.7 Water supply .................................. 47 3.1 Norwegian sovereignty .................. 17 6.3 Provision of services ..................... -

Environment - Norway

Environment - Norway Svalbard Act amendments regulate use of heavy oil Authors Contributed by Arntzen de Besche Advokatfirma AS Eivind Aarnes Nilsen June 11 2012 Background Svalbard Act Prohibition on use of heavy oil Background Due to the melting of polar ice, new transport connections by sea have emerged in the Merete Kristensen Arctic regions around the archipelago of Svalbard. The islands' geographical location provides a strategic advantage for activities that may arise in the region. New discoveries made in the Barents Sea have contributed to the region's image as a potential area for petroleum activities. An ongoing environmental impact assessment of the area around Jan Mayen Island contributes to this view. The previously disputed area in the eastern Barents Sea and around Jan Mayen Island may prove to be a new source of natural resources in an area not subject to legal restrictions as Svalbard is. The Svalbard Treaty, which was signed between Norway, the United States, Denmark, France, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Great Britain, Ireland and the British overseas dominions in 1920, recognises the full and absolute sovereignty of Norway over Svalbard. The signing parties were given equal rights to engage in commercial activities on the islands. As of 2012, Norway and Russia are utilising this right. According to the official Norwegian position on this issue, as a coastal state Norway has jurisdiction over the continental shelf and the maritime areas around Svalbard. This position is a source of conflict between the parties. The United Kingdom and Spain, among others, have made official statements regarding the scope and extent of the treaty, claiming that the treaty applies not only to the islands and the territorial waters, but also to the continental shelf and the maritime zone up to the 200-mile limit. -

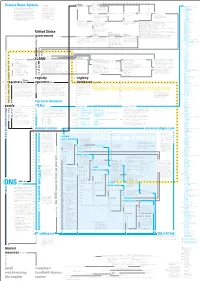

Domain Name System Concept

8 originally chartered standards charters 0 Concept Map organizations include ISoc members form 243 active ccTLDs Domain Name System rely on .ac Ascension Island (licensed) 28 Internet Society (ISoc) is a professional .ad Andorra A concept map is a web of terms. Verbs membership society with more than 150 This diagram is a model of the Domain .ae United Arab Emirates connect nouns to form propositions. organizations and 11,000 individual mem- .af Afghanistan 27 Name System (DNS), a system vital to the Groups of propositions form larger struc- bers from over 182 countries. tures. Examples and details accompany .ag Antigua and Barbuda smooth operation of the Internet. The goal most terms. More important terms re- .ai Anguilla of the diagram is to explain what DNS ceive visual emphasis; less important 11 .al Albania terms, details, and examples are in gray. IETF sponsors working groups are managed by IESG decisions can be appealed to IAB provides advice to IANA functions were moved to .am Armenia is, how it works, and how it’s governed. Terms related to names and addresses write approves .an Netherlands Antilles The diagram knits together many facts (the heart of DNS) are in blue. Terms Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) Internet Engineering Steering Internet Architecture Board (IAB) Internet Assigned Numbers .ao Angola followed by a number link to terms pre- is a voluntary, non-commercial organization Group (IESG) Authority (IANA) originally handled .aq Antarctica about DNS in hopes of presenting a com- ceded by the same number. comprised of individuals concerned with the many of the functions that are now 626,000 .ar Argentina prehensive picture of the system and the evolution of the architecture and operation ICANN’s responsibility. -

Europe: Glaciers of Svalbard, Norway

Glaciers of Europe- GLACIERS OF SVALBARD, NORWAY By OLAV LIESTØL SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF GLACIERS OF THE WORLD Edited by RICHARD S. WILLIAMS, Jr., and JANE G. FERRIGNO U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1386-E-5 Svalbard, Norway, an archipelago in the North Atlantic Ocean, has more than 2,100 glaciers that cover 36,591 square kilometers, or 59 percent of the total area of the islands; images have been used to monitor fluctuations in the equilibrium line and glacier termini and to revise maps CONTENTS Page Abstract.............................................................................. E127 Introduction......................................................................... 127 FIGURE 1. Index map showing the location of Svalbard, the islands that make up the archipelago, the areas covered by glaciers, and the glaciers mentioned in the text .................... 128 TABLE 1. Area encompassed by glaciers on each of the islands in the Svalbard archipelago ........................................ 129 Previous glacier investigations ................................................ 127 FIGURE 2. Index to photogrammetric satellite image and map coverage of glaciers of Svalbard and location of mass-balance measurements made by Norwegian and Soviet glaciologists ................................................. 130 3. Color terrestrial photograph of the grounded front of the Kongsvegen glacier at the head of Kongsfjorden, Spitsbergen, in August 1974 ............................... 131 4. Radio-echosounding cross section (A-A') through -

June 23, 2015 Tents at Poorly Chosen Campsite; Group Also Had Trouble with Weapon Page 3

FREE Weather summary Mostly cloudy, breezy and mild temperatures, with occasional rain through next week. BREAKING: Parliament approves Store Norske bailout. Story at icepeople.net icepeople Full forecast page 3 The world's northernmost alternative newspaper Bearly aware: Polar bear destroys two Vol. 7, Issue 23 June 23, 2015 www.icepeople.net tents at poorly chosen campsite; group also had trouble with weapon Page 3 “ To believe that the governor can rescue people out, regardless of circumstances, is wrong. There is no guarantee for that. - Per Andreassen, police lieutenant Svalbard governor's office MARK SABBATINI / ICEPEOPLE MATS GRANSKOG / NORWEGIAN POLAR INSTITUTE ” Researchers from several countries, left, unload equipment from the Lance research vessel after it docked in Longyearbyen this week, ending a six- month expedition in the sea ice north of Svalbard. At right, a large ice floe used as a work site rapidly breaks up during the expedition's final days. High stakes: Gamblers, Norway's military eyeing odds CRACKING DOWN of a heated Arctic Pages 4-5 Lance ends six-month expedition on thin ice as scientists save gear while floe shatters in a few hours By MARK SABBATINI cake," said Meyer, an oceanography for the Nor- tious ever, sought to profile first-ice sea ice Editor wegian Polar Institute, while helping colleagues "from cradle to grave" by allowing the Lance They spent their final days working fever- to freeze into the ice for extended durations at unload gear from the Lance research vessel af- 'Double moralists': Parliament leaders say ishly on rapidly vanishing sea ice that threat- ter its Tuesday arrival in Longyearbyen.