“The Mallets at Ash”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DEVONSHIRE. 13 Nlrectory.]

' DEVONSHIRE. 13 nlRECTORY.] • LORD LIEUTENANT AND CUSTOS ROTULORUM, EARL FOH'fESCUE K.C.B. Castle hil.l, South l\'Iolton & 36 Lowndes street, London &. W. 1 • • CHAIRMEN OF QUARTER SESSIONS. LORD COLERIDGE, Tbe Chanter's house, Ottery St. Mary. TREHA WKE HERBERT KEKEWICH 1\I.A. Peamore, Alphington, Exeter. Marked thus<> are also Deputy Lieutenants. • .A.claud ,Tohu RichaTd, Groved.ene, F~irview ter.Exmouth Bruce ChM'les Rowland Benry, The Glen, Buckland Acland Admiral Sil: William Alison Dyke hart. C.V.O., Brewer, Bideford F.R.G.S. Wilmead, Middle Warberry road, Torquay Bru.nskill Hubert Fawcett, Buckland Tout Saints,S.Devn Alexander Lt.-Col. Gerald D'Arragon, Townsend house, Bryan Richard Stawell, 33 East street, South Molton Winkleigh Buckingham Rev. Preb. Frederick Finney M.A. Th& Alexander John ;as. Perranwell, Plymouth rd. Taviswck Rectory, Doddiscombsleigh, near Exeter Alexander Philip Pembroke, Laywell, Brixham Buckingham William 'Tbome, Landkey, Barnstaple .A.llen John Burnard Robert F.S.A. Huccaby house, Princetown Alleyne Edward Fitzgerald Massy L.R.C.P. &; S.I. St. Burton Lieut.-Col. Henry Patrick'a, Cullo~mpton Bush Dudley John Campbell, Fort house, South Molton Amery John Sparke, Druid, Ashburton Byres-Leake J'ohn, The Limes, Frant, -sussex *Amory Sir Ian Murra.y Heathcoat bart.C.B.E. Knights- Byrom Edward Clement Athemn, Culver, ~xeter hayes oourt, Tiverto:u Calmady-Hamlyn Charles Hamlyn Hunt M.A. Leawood: Andertcm Edward, Trim stone Barton, West Down Bridestowe Andrews John, Traine, Modbury, Ivybri:dge , ..,. Carew Charles RoLert Sydenham B..A.., M.P. Warni- Andrews Thomas, Camp, Broadwood Widger, Lifton combe, Tiverton . -

Ringing Round Devon

Ringing Round THE GUILD OF DEVONSHIRE RINGERS Devon Newsletter 112: December 2018 ‘to promote an environment in which ringing can flourish’. Last Sunday we witnessed what ‘flourish’ looks like – more of that, Guild Events please. Whilst it is impossible to thank all key individuals by name, I RINGING REMEMBERS would like to pay a special tribute to Vicki Chapman – Ringing Remembers Project Coordinator, Colin Chapman – Coordinator’s ‘roadie’, Alan Regin – Steward of the CCCBR Rolls of Honour, Andrew Hall – developer and administrator of the Ringing Remembers web platform, and Bruce and Eileen Butler – who linked thousands of enquirers to guilds, districts and towers. And there are so many others… My thanks go also to all those who have come to ringing through this route; may you continue to develop in skill and gain many happy years of fulfilment in your ringing. And to that widespread army of ringing teachers who have risen to the challenge of training so many enthusiastic learners – well done! Last Sunday was a day of reflection, a day of commemoration, a day of participation. Bellringers everywhere were able to say: ‘I was there – I remembered’. Christopher O’Mahony The badge issued to all new ringers who registered in time Photo by Lesley Oates Note from our Guild President I think all of our members deserve to be congratulated on the ‘WE REMEMBERED’ – A MESSAGE FROM THE fantastic number of towers in Devon which were heard ringing for PRESIDENT OF THE CENTRAL COUNCIL OF the Armistice on Sunday. Much has been shared on social media CHURCH BELL RINGERS. -

DEVONSHIRE. FAR 857 Daniel Wm

TRADES DmECTORY.] DEVONSHIRE. FAR 857 Daniel Wm. West Youlden, Holsworthy Davey Thomas, Edhill, Farway, Honiton1Dendle William, Sandford, Crediton Danie!William, Willia Thome, Holswrthy Davey'f.Qnarterley,Exe bridge, Tiverton Denner Mrs. Jane, Payhembury, Ottery DanielsD.Luton,Broadhembury,Honiton Davey William, Emsworthy, Broad wood St. Mary Daniels Jn. Gilscot, Alwington,Hideford Widger, Lifton R.S.O DennerWilliam,Broadhembury,Honiton Daniels Patrick,Dawes,Feniton, Honiton Davey William, Higher Hawkerland, Denner William, Southdown, Salcombe Daniels Stephen,Horralake,Inwardleigh, Woodbury Salterton Regis, Sidmouth Exboorne R.S.O Davey William, Middle Rowden, Samp· Denning Daniel, Exeter hill, Cullomptoo Daniels William, Higher Tale, Payhem- ford Courtenay R.S.O Dennis Miss Charlotte, West Worth~ bury, Ottery St. Mary Davey William,Nortb Bet worthy, Buck's North Lew, Beaworthy R.S.O Daniels Wm.Marsh,Clyst Hydon,Exeter mills, Bideford Dennis Edwin, Woodland, Ivybridge Darby Lewis, Karswell, Hockworthy, DaveyW. Youlden,Sth.Tawtn.Okehmptn DennisFras.Venton,HighHamptonR.S.O Wellington (Somerset) Da vieJn.N orthleigh,Goodleigh,Barnstple DennisG. Sticklepath, Tawstock,Barnstpl Darch Henry, Lincombe, Ilfracombe Davies Jas.Hoemore,Up.Ottery,Honiton Dennis George, 'fhorn, Hridford, Exeter Darcb Jas. Horrymill, Winkleigh R.S.O Davies Joseph, Stourton, 'fhelbridge, Dennis Henry, Odam & Lower Coombe, Darch John, Indicknowl, Combmartin, Morchard Bishop R.S.O High Hampton R.S.O Barnstaple Davies Samuel, Beam, Great Torrington Dennis Henry, PiU head, -

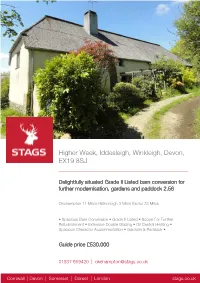

Higher Week, Iddesleigh, Winkleigh, Devon, EX19 8SJ

Higher Week, Iddesleigh, Winkleigh, Devon, EX19 8SJ Delightfully situated Grade II Listed barn conversion for further modernisation, gardens and paddock 2.56 Okehampton 11 Miles Hatherleigh 3 Miles Exeter 32 Miles • Spacious Barn Conversion • Grade II Listed • Scope For Further Refurbishment • Extensive Double Glazing • Oil Central Heating • Spacious Character Accommodation • Gardens & Paddock • Guide price £530,000 01837 659420 | [email protected] Cornwall | Devon | Somerset | Dorset | London stags.co.uk Higher Week, Iddesleigh, Winkleigh, Devon, EX19 8SJ SITUATION is spacious and light with a stunning galleried studio area above the The property occupies a delightful rural setting, close to the living room with full height windows to front and rear. There are confluence of the River Ockment and Torridge. This lovely valley character features including oak screens, Delabole slate flooring setting is known for its prime sporting opportunities with fishing on and a superb inglenook fireplace. Externally, the property is the Torridge and riding and walking on the nearby Tarka trails. The approached via its own private lane. Adjacent to the barn is a yard village of Iddesleigh is a short distance away, being completely and areas of garden and a delightful paddock. There is off road unspoilt and well known for its popular Duke of York public house. parking for numerous vehicles and the gardens, and yard, and the The market town of Hatherleigh is easily accessible with an grounds total just over 2.5 acres, surrounding the property. Further excellent range of services including primary school, supermarket, down the road, another private lane is shared with Numbers 1 and health centre, veterinary surgery and a range of local shops. -

Family Tree Maker

Descendants of Robert Squire Generation No. 1 1. ROBERT1 SQUIRE was born Abt. 1650 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England, and died 26 Nov 1702 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. He married MARY. She died 24 Oct 1701 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. Child of ROBERT SQUIRE and MARY is: 2. i. FRANCIS2 SQUIRE, b. 1670, St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. Generation No. 2 2. FRANCIS2 SQUIRE (ROBERT1) was born 1670 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. He married (1) MARGARET TROWING 17 May 1694 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. She was born Abt. 1670 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England, and died Jun 1700 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. He married (2) ESTER GEATON 06 Jan 1703 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. She was born 1676 in St Giles in the Wood, and died 1750 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. More About FRANCIS SQUIRE: Baptism: 18 Oct 1670, St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England Notes for MARGARET TROWING: Name could be Margaret Crowling. More About FRANCIS SQUIRE and MARGARET TROWING: Marriage: 17 May 1694, St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England More About ESTER GEATON: Baptism: 21 May 1676, St Giles in the Wood Burial: 24 Apr 1750, St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England More About FRANCIS SQUIRE and ESTER GEATON: Marriage: 06 Jan 1703, St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England Children of FRANCIS SQUIRE and MARGARET TROWING are: i. -

DEVONSHIRE. BOO 8C3 Luke Thos.Benj.Io George St.Plymouth Newton William, Newton Poppleford, Perriam Geo

TR.!DES DIRECTORY.] DEVONSHIRE. BOO 8C3 Luke Thos.Benj.Io George st.Plymouth Newton William, Newton Poppleford, Perriam Geo. Hy. 7 Catherinest. Exeter Luke Thos.Hy.42Catherine st.Devonprt Ottery St. Mary PerringA.PlymptonSt.Maurice,Plymptn Luscombe Richard,26 Looest.Piymouth Nex Henry, Welland, Cullompton PerrottChas.106Queenst.NewtonAbbot Luscombe Wm.13 Chapel st.Ea.StonehoiNex William, Uffculme, Cullompton Perry John, 27 Gasking st. Plymouth Lyddon Mrs. Elizh. 125Exeterst.Plymth Nicholls George Hy.East st. Okehampton Perry Jn. P. 41 Summerland st. Exeter Lyddon Geo. Chagford, Newton Abbot Nicholls William, Queen st. Barnstaple PesterJ.Nadder water, Whitestone,Exetr LyddonGeo.jun.Cbagford,NewtonAbbot ~icholsFredk.3Pym st.Morice tn.Dvnprt PP.ters James, Church Stanton, Honiton Lyle Samuel, Lana, Tetcott,Holswortby NormanMrs.C.M.Forest.Heavitree,Extr Phillips Thomas, Aveton Gifford S.O Lyne James, 23 Laira street, Plymouth Norman David, Oakford,BamptonR.S.O Phillips Tbos. 68 & 69 Fleet st. Torquay Lyne Tbos. Petrockstowe,Beaford R.S.O Norman William, Martinhoe,Barnstaple Phillips William, Forest. Kingsbridge McDonald Jas. 15 Neswick st.Plymouth Norrish Robert, Broadhempston, Totnes Phippen Thomas, Castle hill, Axminster McLeod William, Russell st. Sidmouth NorthJas.Bishop'sTeignton, Teignmouth Pickard John, High street, Bideford Mc:MullenDanl. 19St.Maryst.Stonehouse Northam Charles, Cotleigh, Honiton Pike James, Bridestowe R.S.O .Maddock Wm.49Richmond st. Plymouth Northam Charles, Off well Pile E. Otterton, Budleigh Salterton S. 0. :Madge M. 19 Upt.on Church rd. Torquay N orthcote Henry, Lapford, M orchard Pile J. Otter ton, Budleigh Salterton S. 0 1t1adge W. 79 Regent st. Plymouth . Bishop R,S.O Pile WiUiam, Aylesbe!l.re, Exeter J\Jansell Jas. -

Newtown Community Association (Exeter, Devon)

NEWTOWN COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION (EXETER, DEVON) ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31ST DECEMBER 2018 NEWTOWN COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION (EXETER, DEVON) FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31ST DECEMBER 2018 CONTENTS Page Charity Information 1 Trustees’ Report 2-5 Independent Examiner’s Report 6 Statement of Financial Activities 7 Balance Sheet 8 Notes to the Financial Statements 9-14 NEWTOWN COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION (EXETER, DEVON) CHARITY INFORMATION FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31ST DECEMBER 2018 CHARITY NAME: Newtown Community Association (Exeter, Devon) REGISTERED CHARITY NUMBER: 1173331 ADDRESS: 11 Belmont Road Exeter EX1 2HF TRUSTEES: Rory McNeile (Chairman) Stephen Palmer (Secretary) Gareth Carey-Jones (Treasurer) Karolina Borkowska-Knight (from 2nd July 2018) James Cotter Julia Crockett James Leigh (to 19th Feb 2018) Jackie Holdstock Peter Montgomery Judy Pattison (to 1st May 2019) Ella Westland INDEPENDENT EXAMINER: Mr M B J Cronin MAAT FCIE Bowhill Bookkeeping Services 172 Newman Road Exeter EX4 1PQ 1 NEWTOWN COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION (EXETER, DEVON) TRUSTEES’ REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31ST DECEMBER 2018 The trustees present their report together with the financial statements for the year ended 31st December 2018. The financial statements have been prepared in accordance with the accounting policies set out on page 8 and comply with the charity’s Trust Deed, the Charities Act 2011, the Statement of Recommended Practice: Accounting and Reporting by Charities Financial Reporting Standard applicable in the UK and Republic of Ireland (FRS 102) issued on 16th July 2014 and with the Financial Reporting Standard applicable in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland (FRS 102). Structure, Governance and Management Newtown Community Association (Exeter, Devon) is a Charitable Incorporated Organisation (CIO) which is governed by an ‘associated’ model Constitution adopted on 28th May 2017. -

WEST DEVON BOROUGH COUNCIL PLANNING & LICENSING COMMITTEE 05 MARCH 2013 DELEGATED DECISIONS WARD: Bere Ferrers APPLICAT

WEST DEVON BOROUGH COUNCIL PLANNING & LICENSING COMMITTEE 05 MARCH 2013 DELEGATED DECISIONS WARD: Bere Ferrers APPLICATION NO: 03311/2012 LOCATION: Robinswood, Bere Alston, Yelverton, Devon, PL20 7BW APPLICANT NAME: Ms B Poynton APPLICATION: Removal of Condition\Variation of Condition GRID REF: 243184 65604 PROPOSAL: Removal of condition of planning permission 3017/WC/70 to remove agricultural occupancy restriction. CASE OFFICER: Ben Wilcox DECISION DATE: 31/01/2013 DECISION: Conditional Consent WARD: Bere Ferrers APPLICATION NO: 03326/2012 LOCATION: Silver Barn, Hewton House, Bere Alston, Devon, PL20 7BW APPLICANT NAME: Mr P Gentle APPLICATION: Removal of Condition\Variation of Condition GRID REF: 243115 65657 PROPOSAL: Removal of condition 3 of application 4045/2003/TAV to allow full residential use of Silver Barn. CASE OFFICER: Katie Graham DECISION DATE: 25/01/2013 DECISION: Refusal WARD: Bridestowe APPLICATION NO: 03113/2012 LOCATION: 6 and 8 Fore Street, Bridestowe, EX20 4EL APPLICANT NAME: Mr L Beadle APPLICATION: Full GRID REF: 251376 89341 WEST DEVON BOROUGH COUNCIL PLANNING & LICENSING COMMITTEE 05 MARCH 2013 DELEGATED DECISIONS PROPOSAL: Change of use of dwelling to create two dwellings including alterations and extensions CASE OFFICER: Laura Batham DECISION DATE: 15/02/2013 DECISION: Conditional Consent WARD: Buckland Monachorum APPLICATION NO: 00022/2013 LOCATION: Ortac Cottage, Green Lane, Yelverton, PL20 6BW APPLICANT NAME: Mr G Dalton APPLICATION: Full GRID REF: 251222 66967 PROPOSAL: Householder application for a replacement conservatory. CASE OFFICER: Ben Dancer DECISION DATE: 11/02/2013 DECISION: Conditional Consent WARD: Buckland Monachorum APPLICATION NO: 03309/2012 LOCATION: 17 Seaton Way, Crapstone, Yelverton, Devon, PL20 7UZ APPLICANT NAME: Mr & Mrs B Sutton-Soanes APPLICATION: Full GRID REF: 250023 67615 PROPOSAL: Householder application for erection of conservatory. -

Devon-Newfoundland

PROGRAMME OF EVENTS 3rd – 16th April 2017 The Devonshire Association Exploring and celebrating all aspects of Devon THE DEVON-NEWFOUNDLAND STORY ABOUT US Introduction Devonshire Association (Registered Charity No 252468) Devon has strong historic links with the Canadian Province of Newfoundland dating back to the 16th-century, with boats from local The Devonshire Association (DA) is a non-prof t-making body which was ports sailing annually to waters of Newfoundland to f sh for cod. Initially formed in 1862 and is dedicated to the study and appreciation of all things men left Devon in April and returned in the autumn, but gradually land Devonian. It is the only society concerned with every aspect of the county bases were established and they began to overwinter. In 1583, the Devon and is one of the oldest of its kind in Britain. Membership is about 1,300. mariner, Sir Humphrey Gilbert, claimed Newfoundland as the f rst English The organisation consists of an Executive Committee; seven regional branches – Axe Valley, overseas colony. Bideford, East Devon, Exeter, South Devon, Plymouth & District, Tavistock & West Devon; This celebration, organised by the Devonshire Association working with and nine specialist sections – Botany, Buildings, Entomology, Geology, History, Industrial the Devon Family History Society, marks nearly 500 years of contact and Archaeology, Literature & Art, Music and Photography. interaction between the two communities. Whilst people in Newfoundland Over 100 activities are organised each year throughout the county – talks, exhibitions, are very aware of their Devon connections, Devonians are less well- excursions, f eld trips, concerts and symposia. There is also an Annual Conference held each informed about the historic importance of Newfoundland to the economy year in a dif erent town and a President’s Symposium on a subject of his or her choice. -

Ash House WINKLEIGH DEVON • a Magnificent Grade II Listed Country House in a Mature Parkland Setting with Remarkable Uninterrupted Views Towards Dartmoor

• Ash House WINKLEIGH DEVON • A magnificent Grade II Listed country house in a mature parkland setting with remarkable uninterrupted views towards Dartmoor. The ring-fenced estate is wonderfully peaceful and private, with a number of secondary dwellings and extensive outbuildings with stabling. Following a sympathetic and extensive refurbishment, Ash House is presented in superb order and is an incredibly efficient house to run. Ash House WINKLEIGH DEVON Exeter 27 miles - the North Devon Coast at Croyde 31 miles Dartmoor 9 miles Exeter St David’s Station 27 miles (All distances are approximate) Ash House Entrance hall • 4 principal reception rooms • Study • Billiard room with bar Conservatory • Large kitchen / breakfast room • Wine cellar • Boot room 4 principal bedroom suites • Home office • Playroom • Second floor flat with 2 bedroom suites Stable Cottage: Attached 4 bedroom annex with gym and independent access Aviary Villa: Attached 1 bedroom guest apartment with independent access Gardener’s Cottage: Detached 3 bedroom cottage with private garden Farm Flat: Independent 2 bedroom apartment above outbuildings Extensive modern farm buildings including high quality stabling and loose boxes Stunning formal walled and woodland gardens • Georgian summer house • Hard tennis court Heated swimming pool • Parkland • Pasture • Woodland In all about 125 acres (50.55 hectares) Knight Frank LLP Knight Frank LLP Savills Savills 19 Southernhay East, Exeter 55 Baker Street 33 Margaret Street The Forum, Barnfield Road, Devon EX1 1QD London W1U 8AN London W1G 0JD Exeter EX1 1QR Tel: +44 1392 423 111 Tel: +44 20 7861 1528 Tel: +44 20 7016 3820 Tel: +44 1392 455 741 edward.clarkson@ james.mckillop@ [email protected] [email protected] knightfrank.com knightfrank.com www.knightfrank.co.uk www.savills.co.uk These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. -

Torridge District Council Planning Decisions Between 22/3/2019 And

Torridge District Council Planning Decisions Between 22/3/2019 and 22/5/2019 List of Applications Application Officer Proposal and Address Applicant Decision/Date No: PERMITTED 1/0036/2019/ Sarah Works to a Tree covered by a TPO - PARAPP TRE Boyle 20 Buckland View, Bideford, Devon. 02.04.2019 1/0086/2019/ Sarah Works to tree covered by Tree Mrs Beale PARAPP TRE Boyle Preservation Order (T1 Lime - Fell, 03.04.2019 die back in crown, shedding of limbs) - 4 Nilgala Close, Bideford, Devon. 1/0095/2019/ Ryan TRE Steppel Works to Mature Copper Beech Wills Tree TPOA TPO/0006/2004) - reduce weight Services 09/04/2019 on southern limb and slightly reduce number of branches on northern stem to lighten crown and incorporate some corrective pruning on previous poor pruning work. - Beeches, 1A St Helens, Padshall 1/1050/2014/ Sarah Outline application for up to 27 Mr B Chapple PER OUTM Boyle dwellings - Land Adjacent To , 16.05.2019 Orleigh Close, Buckland Brewer. 1/1295/2015/ Sarah Variation of Section 106 Agreement Homes For PER SEC106 Boyle - Flat 1, Whitlock Court, 19 The Holsworthy 03.04.2019 Square. 1/0831/2017/ Shaun 7 Flats and associated parking Clearsky PER FUL Harringt (Amended Plans) - 76 Atlantic Way, Developments 10.04.2019 on Westward Ho!, Devon. Ltd 1/1021/2018/ Debbie Conversion of agricultural barn to Mr J. Cawsey PER FUL Fuller 1No. dwelling (Amended Plans) - 26.04.2019 Haddacott Farm, Huntshaw, Torrington. 1/1031/2018/ James Change of use from agricultural to Mr Michael PER FUL Jackson mixed used of agricultural and Jordan 03.05.2019 equestrian and erection of stable building. -

DEVONSHIRE. FAS 993 .Keal Miss Margaret, Newland, Swym- King Jn

TRADES DIRECTORY.] DEVONSHIRE. FAS 993 .Keal Miss Margaret, Newland, Swym- King Jn. Waterbouse, Exbourne R.S.O Kneebone lV:illiam, Pristacott, As.h- bridge, Barnstaple King Rd. Buckley, Sidbury, Sidmouth water, Beaworthy R.S.O lieats R. Five Elms, Northam,Bideford King Richard, Higher Westacott, In- Kneebone William, Tucker's park, Ex- Keen George, Kenn, Exet-er wardleigh, Okehampton bourne R.S.O Keirle John ·waiter, Coombe, Good King W. Deckport, Hatherleigh R.S.O Knight David, Burrow, Black Tarring- leigh, Barnstaple King W.Starcombe,Sidbury,Sidmouth ton, Highampton R.S.O Kelland John, West Anstey, Dulverron King W. T. Stockley, Highampton KnigbtE.Cranbam mill,Hartland,Bdefd RS.O. (Somerset) R. S. 0 Knight George, Higher Hunston, Xelland Richard, South view, Lapford, King Walter, Higher Bowcombe, Ug- North Molton, South Molton ~orchard Bishop R.S.O borough, Ivybridge Knight Henry, Oakwell, Kingsnymp- Kelland R. Exe land, Bicklgh. Tivertn King William, Downhouses, Inward- ton, Chulmleig-h Xelland Robert, Frost, Coleridge, leigh, Okehampton Knight James, Hall, Bl:«!k Torrington, Wembworthy R.S.O King William, King-ston, Kingbridge Highampton R..S.O 'Krlland Rt. Yate, Cadeleigh, Tiverton King William, Stockhay, Meeth, Ilath- Knight Jas. Halwill, Beaworthy R.S.O Kelland William Henry, !lliddlecott, erleigh R.S. 0 Knight .T. Bnsland, Cadeleigh, Tivertn ~!orchard Bishop R.S.O Kingdom Mrs. Ann, :Molland, S. Molton Knight John, Secmaton, Dawlish .Kelly Edward & Henry, Grawley, Mil Kin!!dom Willinm, ~~estway, Cruwys Knight John Dennis, Gunnacott,Olaw- ton Damerel, Brandis Corner R.S.O Morchard, Tiverton ton, Holswortby .Kelly John & Sons, Black Torrington, Kingdon Chas. Rudge Rew, Morchard Knight Michael, Stowford, Halwill, Highampton R.S.O Bishop R.S.O Beaworthy R.S.O ..Kelly Arthur, ::\Iiddle moor, Whit Kingdon Fred, Down Hayne, Sand- Knight Mrs.Kiddons, Exminster,Exetr • church, Tavistock ·ford, Crediton Knight Robert, Chains, Sampford Pev- Kelly C.