Writing Instruction for Jamaican University Students: a Case for Moving Beyond the Rhetoric of Transparent Disciplinarity at the University of the West Indies, Mona

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barbados Archives Department FINDING

Barbados Archives Department RECORDS OF THE BARBADOS SYNAGOGUE RESTORATION PROJECT (BSRP) FINDING AID Prepared by Amalia S. Levi Revised: February 2017 1 Contents IDENTITY STATEMENT ................................................................................................................................... 4 CONTEXT ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 CONTENT AND STRUCTURE .......................................................................................................................... 5 CONDITIONS OF ACCESS AND USE ................................................................................................................ 7 ALLIED MATERIALS ........................................................................................................................................ 7 DESCRIPTION CONTROL ................................................................................................................................ 9 CONTROLLED ACCESS HEADINGS (LCSH) ...................................................................................................... 9 DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................................................... 10 SUB-COLLECTION 1: PHASE I – NIDHE ISRAEL SYNAGOGUE RESTORATION ........................................... 10 SERIES 1.01: SYNAGOGUE RESTORATION PROCESS .......................................................................... -

The National Strategic Plan of Barbados 2005-2025

THE NATIONAL ANTHEM In plenty and in time of need When this fair land was young Our brave forefathers sowed the seed From which our pride is sprung, A pride that makes no wanton boast Of what it has withstood That binds our hearts from coast to coast - The pride of nationhood. Chorus: We loyal sons and daughters all Do hereby make it known These fields and hills beyond recall Are now our very own. We write our names on history’s page With expectations great, Strict guardians of our heritage, Firm craftsmen of our fate. The Lord has been the people’s guide For past three hundred years. With him still on the people’s side We have no doubts or fears. Upward and onward we shall go, Inspired, exulting, free, And greater will our nation grow In strength and unity. 1 1 The National Heroes of Barbados Bussa Sarah Ann Gill Samuel Jackman Prescod Can we invoke the courage and wisdom that inspired and guided our forefathers in order to undertake Charles Duncan O’neal the most unprecedented Clement Osbourne Payne and historic transformation in our economic, social and physical landscape since independence in Sir Hugh Springer 1966? Errol Walton Barrow Sir Frank Walcott Sir Garfield Sobers Sir Grantley Adams 2 PREPARED BY THE RESEARCH AND PLANNING UNIT ECONOMIC AFFAIRS DIVISION MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND ECONOMIC AFFAIRS GOVERNMENT HEADQUARTERS BAY STREET, ST. MICHAEL, BARBADOS TELEPHONE: (246) 436-6435 FAX: (246) 228-9330 E-MAIL: [email protected] JUNE, 2005 33 THE NATIONAL STRATEGIC PLAN OF BARBADOS 2005-2025 FOREWORD The forces of change unleashed by globalisation and the uncertainties of international politics today make it imperative for all countries to plan strategically for their future. -

Presidentes América Central

Presidentes | América Central BARBADOS La isla de Barbados se encuentra ubicada entre el Mar Caribe y el Océano Atlántico. Está dentro del grupo de las antillas menores que formar un arco insular. Es uno de los paí- ses más desarrollados de América, luego de Estados Unidos y Canadá. SISTEMA DE GOBIERNO La isla se ha convertido en una nación independiente en 1966. Los dos principales par- tidos políticos son: Partido Laborista de Barbados (BLP) y Partido Laborista Democrático (DLP). Han permanecido en el poder alternativamente. Llaro Court. El sistema de gobierno está basado en una monarquía constitucional con dos La isla se ha cámaras: el Senado con 21 representantes, y la Asamblea Legislativa con 28. Los convertido en una integrantes de ambas cámaras son elegidos por medio del sufragio universal por un período de cinco años. La Reina Isabel II es la jefa de estado, un Gobernador General nación independiente representa su poder. Al frente del poder ejecutivo está el Primer Ministro. en 1966. 144 www.elbibliote.com Presidentes | América Central ÚLTIMOS GOBERNADORES GENERALES Gobernadores Períodos Sir Arleigh Winston Scott (1967-1976) Sir Deighton Lisle Ward (1976-1984) Sir Hugh Springer (1984-1990) Dame Nita Barrow (1990-1995) Sir Denys Williams (1995-196) Sir Cliff ord Husbands 1996 (1996-) ÚLTIMOS PRIMEROS MINISTROS Primeros Ministros Períodos Errol Walton Barrow 1966 – 1966 (1966) Tom Adams 1976 – 1985 (1976-1985) Bernard St. John 1985 – 1986 (1985-1986) Errol Walton Barrow 1986 – 1987 (1986-1987) Erskine Sandiford 1987 – 1994 (1987-1994) Owen Arthur 1994 – 2008 (1994-2008) David Th ompson 2008 – 2010 (2008-2010) Freundel Stuart 2010 – actualidad (2010-) GOBERNADORES GENERALES SIR ARLEIGH WINSTON SCOTT Período de Mandato: 1967 – 1976 Realizó sus estudios en la Escuela Giles Boys, más tarde se cambió al prestigioso colegio Harrison College donde realizó sus estudios secundarios. -

Sir Hugh Springer

Presidentes | América Central SIR DEIGHTON LISLE WARD Período de Mandato: 1976 - 1984 Se graduó del Colegio Harrison en Bridgetown. Su carrera política comenzó en 1958 cuando fue uno de los candidatos del Partido Laboral de Barbados, en esa oportunidad ganaron cuatro de los cinco escaños de la Cámara de Representantes del Parlamento Federal de Barbados. Colegio Harrison. Entre 1976 y 1984 Deighton Ward ocupó el cargo de Gobernador General. Fue nombrado Caballero de la Grand Cross de la Orden Real Victoriana y también fue Caballero de Saint Michael y Saint George. SIR HUGH SPRINGER Período de mandato: 1984 - 1990 Estudió leyes en el Inner Temple, en London. En lo que respecta a su carrera política, fue reconocido como un excelente administrador. Fue el primer Secretario General de la Unión de trabajadores de Barbados entre 1940 a 1947. Ese año se fue de Barbados para ocupar el cargo de Secretario de universidad de West Indies en Jamaica. Tuvo una larga carrera como profesional: Fue miembro de la Cámara de la Asamblea. Secretario General del Partido Laboral. Gobernador Interino. Sir Hugh Springer. Comandante en Jefe de Barbados. Director de Commonwealth Education Liaison Unit. 147 Presidentes | América Central Secretario General de la Commonwealth. Secretario General de la Asociación de Universidades de la Commonwealth. Sus habilidades administrativas benefi ciaron la Liga Sus habilidades administrativas benefi ciaron la Liga Progresista, en la misma se desempeñó como Secretario General y creo una sección económica de registros. En Progresista. 1944, fue nombrado miembro del Comité Ejecutivo. West Indies University. En 1946, se hizo responsable de la educación, del Departamento Jurídico, de la Agri- cultura y la Pesca. -

Cavehill Uwi Report 2006.Pdf

C o n t e n t s Chairman’s Statement ..............................3 Principal’s Report .....................................5 Teaching and Learning ...........................21 Research and Development ...................28 Publications ............................................31 Student News .........................................33 Administrators of the Campus ...............36 Members of Campus Council ................37 Campus Management ............................38 Financial Summary .................................41 Outreach – University and Campus .......43 Outreach – Faculties and Departments ..44 Campus Events ......................................47 Saluting Achievement .............................49 Recognition ................................................... 51 Statistics (charts) ....................................54 Benefactors ............................................64 International Visitors ...............................67 “[This] Report points to success in our efforts to open up access to larger numbers of those seeking entry to our Campus; it speaks of important expansion and innovation in programming; the provision of enhanced student amenities; improvements to the physical infrastructure and administrative procedures; and the development of a graduate studies and research agenda tailored to regional development needs.” The University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus ANNUAL REPORT 2006 Chairman’s Statement The Cave Hill Campus’ Annual Report 2005-2006 In a dynamic and competitive global educational -

Resource Booklet 2016

1 2 his edition of the Independence Activity its flag, always uphold and defend their honor, booklet highlights activities and things live the life that would do credit to our nation TBarbadian as we celebrate Fifty years of where ever you go. Learn the words to the Independence, our Golden Jubilee. national anthem and always sing it lustily and Themed ‘Pride and Industry, Celebrating 50' is with pride. a reflection and celebration of our development Let us all continue to be proud of our heritage as an Independent Nation since November 30, and all that it represents. Do whatever is 1966. necessary to uphold the standards set by our Throughout the years of our development since forefathers, so that together we can move gaining Independence, we have been able to forward to an even brighter and better Barbados build a solid foundation which has enabled the over the next fifty years and beyond. country to grow from strength to strength in Listen, look and learn from the many historical, every area of our national, social, physical and wholesome and educational activities you political development. will be exposed to during the celebrations. You, the children of Barbados are our future, Show your patriotism and help to preserve the whatever that future holds is in your hands. characteristics that are truly Barbadian. You will be mandated to move us forward Enjoy the activities prepared to highlight ‘things and remember, always keep the words of Barbadian’ and may you have an enjoyable and our National Pledge foremost in your minds. memorable 50th Independence Celebrations. -

Barbados Advocate

Established October 1895 Scientists’ surveillance hindered by poor visibility Page 4 Wednesday April 28, 2021 $1 VAT Inclusive New policy UNEQUAL Concern expressed on quality about curtailing of Labour Day likely TREATMENT activities coming WHY is it that trade unionists in the 13th June 1980 Movement, wants Their comments came during a virtual Barbados cannot gather, whilst so- answered. He has also received the sup- press conference, which they convened cially distanced, to celebrate Labour port of General Secretary of the to discuss their Labour Day Programme, THE Cabinet of Barbados will soon have Day on May 1st, but religious Caribbean Movement for Peace and which will now take place over the Zoom before it for approval, a paper that out- groups, which in some cases have Integration, David Denny, who argues online platform on May 1st, 2021, given lines the development of a national pol- contributed to the spread of COVID- that May 1st is an important day for the restrictions in place on account of the icy on quality for this country. 19, can freely congregate? workers in Barbados and the curtailing pandemic. Word of this has come from Minister of This is the question Attorney-at-Law, therefore of Labour Day activities should Energy, Small Business and Lalu Hanuman who is the coordinator of be frowned upon. ANSWERS on Page 3 Entrepreneurship, Kerrie Symmonds, who said this policy will speak to the quality of services provided and goods produced here. He made the disclosure while delivering the keynote address yes- terday morning during the virtual launch of the Caribbean Micro, Small and Medium Enterprise Centre. -

By William Anderson Gittens Author, Cultural Practitioner, Media Arts Specialist and Publisher

PPeeooppllee Vol.2 By William Anderson Gittens Author, Cultural Practitioner, Media Arts Specialist and Publisher ISBN 976Page-8080 1 of 90 -59-0 In memory of my father the late Charles A. Gittens People Vol.2 By William Anderson Gittens Dip. Com. B.A. Media Arts, Author, Media Arts Specialist, Post Masters Works in Cultural Studies, and Publisher ISBN 976-8080-59-0 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of William Anderson Gittens the copyright owner. Typesetting, Layout Design, Illustrations, and Digital Photography by William Anderson Gittens Edited by Stewart Russell, Magnola Gittens and William Anderson Gittens Published by William Anderson Gittens Printed by Illuminat (Barbados) Ltd. Email address devgro@ hotmail.com Twitter account William Gittens@lisalaron https://www.facebook.com/wgittens2 www.linkedin.com/pub/william-gittens/95/575/35b/ Page 2 of 90 Foreword Through the lenses of a Media Arts Specialist I have discovered that People are ambassadors of their Creator and representatives of their Diaspora, operating within the universal space 1 . In this space the people whom I have referenced in this text are part of the world’s population totalling seven billion 2 who provided representation3, shared ideas and habits they would have learnt, with their generation and ultimately with generations to come.”4 William Anderson Gittens Dip. Com. B.A. Media Arts; Author, Media Arts Specialist, Post Masters Works in Cultural Studies, and Publisher 1 Elaine Baldwin Introducing Cultural Studies (Essex: Prearce Hall,1999).p.141. -

Seventh-Day Adventists in Barbados OVERA CENTURY M ADVENTISM 1884 - 1991 ASTR Research Center Ubrary

Seventh-day Adventists in Barbados OVERA CENTURY M ADVENTISM 1884 - 1991 ASTR Research Center Ubrary General Conference of Seventh-day A ttortisi» Over a Century of Adventism 1884-1991 Genere! Conference of Seventh-day Adventists — • OVERA CENTURY OF ADVENTISM 1884-1991 Glen O. Phillips East Caribbean Conference of Seventh-Day Adventists East Caribbean Conference of S.D.A. P.O. Box 223 Bridgetown Barbados, West Indies. Copyright © 1991 by Glen O. Phillips First published 1991 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part o f this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except by reviewers for the public press, without the prior written permission o f the copyright owner. ISBN 976 8083 37 9 East Caribbean Conference o f S.D.A. Printed by Caribbean Graphics & Letchworth Ltd.. Barbados IV Contents Page List of Appendices vi Foreword vii Acknowledgement ix Introduction 1 Chapter I 4-10 The Corning of Seventh-Day Adventism 1884-1891 Chapter II 11-20 The Formation of the Adventist Church 1891-1900 — The Founding of the First Church, 1891 — The Arrival of the First Permanent Adventist Minister, 1896 — The Establishment of Adventist Medical Work, 1898 — The plans for the Building of a Church, 1899 Chapter III 21-38 The Early Adventist Community, 1900-1924 — A letter from Mrs. E.G. White to the Barbadian Church — Adventists’ Response to the Epidemic of 1902 — Barbados Selected as Adventist Headquarters in 1904 — Overcoming Problems and Prosperity, 1910-1923 Chapter IV 39-47 Entering the North, 1924-1930 Chapter V 48-59 The Years of Consolidation, 1930-1945 — 1931 Evangelistic Series at Bank Hall — Leeward Island Mission Office comes to Barbados, 1935 — The Promotion of Youth and Literature Programs, 1936 — The Death of Dr. -

January 2008 Vol 5 Issue 1 Circulation 12,000

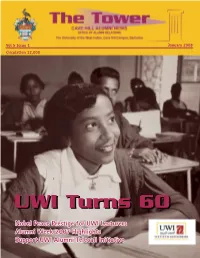

Vol 5 Issue 1 January 2008 Circulation 12,000 The Tower January 2008 Photograph compliments Sandy Pitt editor’s note Best wishes to the UWI alumni community for the new year! 2008 marks the diamond anniversary of the UWI. On this very special occasion, The Tower takes a look back at the early years 1948 – 1963, the year in which the Cave Hill Campus was established. The dreams, the hopes and the expectations for our University, one of the Caribbean’s truly regional institutions, are captured in the expression on the face of Sheila Sealy (neé Payne), first year Arts student in March President of UWIAA Maxine McClean Chats with alumnus Chris 1955 on our cover, reproduced with her kind Sinckler, while Roseanne Maxwell and Sonia Johnson, of the Business Development and Alumni Relations Office look on. (UWI permission. In this edition, our feature article Graduate Fair, 2007.) takes us on a journey back to those formative years of the University College of the West Indies Graduate (UCWI) through the words of Jeremy Taylor in a 1993 Caribbean Beat article and photographs Recruitment Drive provided by the Federal Archives at the Cave Hill Campus and the Mona Library. We catch a glimpse The UWI, Cave Hill Campus studies and research. We of the excitement of the dream that was UCWI held its first ever Graduate need to have at least 20% and gain a sense of the historical significance Recruitment Fair in of our students enrolled in of that fledgling institution, its survival through Barbados at the Sherbourne higher degrees, so we are the collapse of the West Indies Federation and Conference Centre on focusing on a new policy with its struggle to establish itself as the uniquely November 7, 2007. -

Sir Grantley Herbert Adams

SIR GRANTLEY HERBERT ADAMS Political legend, father of democracy, leader distinguished, visionary politician are but a few of the accolades used to describe Grantley Herbert Adams, first Premier of Barbados, and one of the Caribbean Region's most outstanding political leaders. The unprecedented accomplishments of Sir Grantley in the political liberation of Barbados, and advancing the cause of workers and the poor exploited masses, led his numerous supporters to perceive him as a messianic figure. The respect and reverence held for this great leader, often referred to as 'Moses" and "Messiah", lay in his unique ability to relate to and understand the needs of the ordinary folk in his country. On April 28, 1898, the course of Barbados history was charted with the birth of Grantley Herbert Adams to Fitzherbert Adams and the former Rosa Frances Turney. Born at Colliston Government Hill, St. Michael, he was the third of seven offspring of this union. He was educated at St. Giles School and Harrison College in Barbados. Sir Grantley, as he was popularly known, excelled and won a scholarship in 1918 which afforded him the opportunity to attend Oxford University in England pursuing studies in Classics and Jurisprudence. Grantley Adams was admitted to the Bar at Grey's Inn and functioned as a Counsel of Her Majesty, the Queen of England. He returned to Barbados in 1925, and in 1929 the former Grace Thorne became Mrs. Grantley Adams. Following his father's path, their only child, Tom Adams, also entered the legal profession and was elected the second Prime Minister of Barbados. -

Highest Quality at Vintage Reggae Show

Established October 1895 See Inside Sunday May 1, 2016 $2 VAT Inclusive DREAM STILL ALIVE BARBADIANS are still ing. There is always showing an interest in Many Barbadians still desire ‘a piece of the rock’ money in the economy,the purchasing land challenge is where it is be- though they may be Fredrick, shared this with Sandiford Centre. still a lot of land that is leaving school [and] there cause it moves around but doing so at a slower the media while speaking “From what we have available. People will al- are new people getting op- essentially,it still is pretty rate than in years past. on the sidelines of the sec- seen, from what I have ob- ways be buying because portunities. People say slow right now. There is Director of Saturday’s ond annual event held at served [and] from listen- there is a cycle in the econ- that land is not selling but not the kind of movement Real Estate Expo, Derrick the Lloyd Erskine ing to the experts, there is omy,there are new people land will always be sell- HOMES on page 6 Highest quality at Vintage Reggae show THE THOUSANDS of Dance continues to draw artistes of regional and in- show from the grounds or vintage reggae fans who large diverse crowds, with ternational acclaim. in the stands. made their way to the a line-up which not only This year,the stage was Local artistes Super Kensington Oval on looked refreshingly good noticeably closer to the Rubien and John King Friday night did not leave on paper, but took music Worrell,Weekes & Walcott ably opened up the live disappointed.