Marine Ecosystems and Global Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regime Shifts in the Anthropocene: Drivers, Risk, and Resilience

Supplementary Information for Regime Shifts in the Anthropocene: drivers, risk, and resilience by Juan-Carlos Rocha, Garry D. Peterson & Reinette O. Biggs. This document presents a worked example of a regime shift. We first provide a synthesis of the regime shift dynamics and a causal loop diagram (CLD). We then compare the resulting CLD with other regime shifts to make explicit the role of direct and indirect drivers. For each regime shift analyses in this study we did a similar literature synthesis and CLD which are available in the regime shift database. A longer version of this working example and CLDs can be found at www.regimeshifts.org. 1. Kelps transitions Summary. Kelp forests are marine coastal ecosystems located in shallow areas where large macroalgae ecologically engineer the environment to produce a coastal marine environmental substantially different from the same area without kelp. Kelp forests can undergo a regime shift to turf-forming algae or urchin barrens. These shift leads to loss of habitat and ecological complexity. Shifts to turf algae are related to nutrient input, while shifts to urchin barrens are related to trophic-level changes. The consequent loss of habitat complexity may affect commercially important fisheries. Managerial options include restoring biodiversity and installing wastewater treatment plants in coastal zones. Kelps are marine coastal ecosystems dominated by macroalgae typically found in temperate areas. This group of species form submarine forests with three or four layers, which provides different habitats to a variety of species. These forests maintain important industries like lobster and rockfish fisheries, the chemical industry with products to be used in e.g. -

Data Structure

Data structure – Water The aim of this document is to provide a short and clear description of parameters (data items) that are to be reported in the data collection forms of the Global Monitoring Plan (GMP) data collection campaigns 2013–2014. The data itself should be reported by means of MS Excel sheets as suggested in the document UNEP/POPS/COP.6/INF/31, chapter 2.3, p. 22. Aggregated data can also be reported via on-line forms available in the GMP data warehouse (GMP DWH). Structure of the database and associated code lists are based on following documents, recommendations and expert opinions as adopted by the Stockholm Convention COP6 in 2013: · Guidance on the Global Monitoring Plan for Persistent Organic Pollutants UNEP/POPS/COP.6/INF/31 (version January 2013) · Conclusions of the Meeting of the Global Coordination Group and Regional Organization Groups for the Global Monitoring Plan for POPs, held in Geneva, 10–12 October 2012 · Conclusions of the Meeting of the expert group on data handling under the global monitoring plan for persistent organic pollutants, held in Brno, Czech Republic, 13-15 June 2012 The individual reported data component is inserted as: · free text or number (e.g. Site name, Monitoring programme, Value) · a defined item selected from a particular code list (e.g., Country, Chemical – group, Sampling). All code lists (i.e., allowed values for individual parameters) are enclosed in this document, either in a particular section (e.g., Region, Method) or listed separately in the annexes below (Country, Chemical – group, Parameter) for your reference. -

Species Status Assessment Emperor Penguin (Aptenodytes Fosteri)

SPECIES STATUS ASSESSMENT EMPEROR PENGUIN (APTENODYTES FOSTERI) Emperor penguin chicks being socialized by male parents at Auster Rookery, 2008. Photo Credit: Gary Miller, Australian Antarctic Program. Version 1.0 December 2020 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Ecological Services Program Branch of Delisting and Foreign Species Falls Church, Virginia Acknowledgements: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Penguins are flightless birds that are highly adapted for the marine environment. The emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri) is the tallest and heaviest of all living penguin species. Emperors are near the top of the Southern Ocean’s food chain and primarily consume Antarctic silverfish, Antarctic krill, and squid. They are excellent swimmers and can dive to great depths. The average life span of emperor penguin in the wild is 15 to 20 years. Emperor penguins currently breed at 61 colonies located around Antarctica, with the largest colonies in the Ross Sea and Weddell Sea. The total population size is estimated at approximately 270,000–280,000 breeding pairs or 625,000–650,000 total birds. Emperor penguin depends upon stable fast ice throughout their 8–9 month breeding season to complete the rearing of its single chick. They are the only warm-blooded Antarctic species that breeds during the austral winter and therefore uniquely adapted to its environment. Breeding colonies mainly occur on fast ice, close to the coast or closely offshore, and amongst closely packed grounded icebergs that prevent ice breaking out during the breeding season and provide shelter from the wind. Sea ice extent in the Southern Ocean has undergone considerable inter-annual variability over the last 40 years, although with much greater inter-annual variability in the five sectors than for the Southern Ocean as a whole. -

Forage Fish Management Plan

Oregon Forage Fish Management Plan November 19, 2016 Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Marine Resources Program 2040 SE Marine Science Drive Newport, OR 97365 (541) 867-4741 http://www.dfw.state.or.us/MRP/ Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Purpose and Need ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Federal action to protect Forage Fish (2016)............................................................................................ 7 The Oregon Marine Fisheries Management Plan Framework .................................................................. 7 Relationship to Other State Policies ......................................................................................................... 7 Public Process Developing this Plan .......................................................................................................... 8 How this Document is Organized .............................................................................................................. 8 A. Resource Analysis .................................................................................................................................... -

Multidecadal Warming and Density Loss in the Deep Weddell Sea, Antarctica

15 NOVEMBER 2020 S T R A S S E T A L . 9863 Multidecadal Warming and Density Loss in the Deep Weddell Sea, Antarctica VOLKER H. STRASS,GERD ROHARDT,TORSTEN KANZOW,MARIO HOPPEMA, AND OLAF BOEBEL Alfred-Wegener-Institut Helmholtz-Zentrum fur€ Polar- und Meeresforschung, Bremerhaven, Germany (Manuscript received 16 April 2020, in final form 10 August 2020) ABSTRACT: The World Ocean is estimated to store more than 90% of the excess energy resulting from man-made greenhouse gas–driven radiative forcing as heat. Uncertainties of this estimate are related to undersampling of the subpolar and polar regions and of the depths below 2000 m. Here we present measurements from the Weddell Sea that cover the whole water column down to the sea floor, taken by the same accurate method at locations revisited every few years since 1989. Our results show widespread warming with similar long-term temperature trends below 700-m depth at all sampling sites. The mean heating rate below 2000 m exceeds that of the global ocean by a factor of about 5. Salinity tends to increase—in contrast to other Southern Ocean regions—at most sites and depths below 700 m, but nowhere strongly enough to fully compensate for the warming effect on seawater density, which hence shows a general decrease. In the top 700 m neither temperature nor salinity shows clear trends. A closer look at the vertical distribution of changes along an ap- proximately zonal and a meridional section across the Weddell Gyre reveals that the strongest vertically coherent warming is observed at the flanks of the gyre over the deep continental slopes and at its northern edge where the gyre connects to the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC). -

Multiple Stable States and Regime Shifts - Environmental Science - Oxford Bibliographies 3/30/18, 10:15 AM

Multiple Stable States and Regime Shifts - Environmental Science - Oxford Bibliographies 3/30/18, 10:15 AM Multiple Stable States and Regime Shifts James Heffernan, Xiaoli Dong, Anna Braswell LAST MODIFIED: 28 MARCH 2018 DOI: 10.1093/OBO/9780199363445-0095 Introduction Why do ecological systems (populations, communities, and ecosystems) change suddenly in response to seemingly gradual environmental change, or fail to recover from large disturbances? Why do ecological systems in seemingly similar settings exhibit markedly different ecological structure and patterns of change over time? The theory of multiple stable states in ecological systems provides one potential explanation for such observations. In ecological systems with multiple stable states (or equilibria), two or more configurations of an ecosystem are self-maintaining under a given set of conditions because of feedbacks among biota or between biota and the physical and chemical environment. The resulting multiple different states may occur as different types or compositions of vegetation or animal communities; as different densities, biomass, and spatial arrangement; and as distinct abiotic environments created by the distinct ecological communities. Alternative states are maintained by the combined effects of positive (or amplifying) feedbacks and negative (or stabilizing feedbacks). While stabilizing feedbacks reinforce each state, positive feedbacks are what allow two or more states to be stable. Thresholds between states arise from the interaction of these positive and negative feedbacks, and define the basins of attraction of the alternative states. These feedbacks and thresholds may operate over whole ecosystems or give rise to self-organized spatial structure. The combined effect of these feedbacks is also what gives rise to ecological resilience, which is the capacity of ecological systems to absorb environmental perturbations while maintaining their basic structure and function. -

Cascading Regime Shifts Within and Across Scales Juan C

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/364620; this version posted July 7, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Cascading regime shifts within and across scales Juan C. Rocha1,2, Garry Peterson1, Örjan Bodin1, Simon A. Levin3 1Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University, Kräftriket 2B, 10691 Stockholm 2Beijer Institute, Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences, Lilla Frescativägen 4A, 104 05 Stockholm 3Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, Princeton University, 106A Guyot Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544-1003 Abstract Regime shifts are large, abrupt and persistent critical transitions in the function and structure of systems (1, 2 ). Yet it is largely unknown how these transitions will interact, whether the occurrence of one will increase the likelihood of another, or simply correlate at distant places. Here we explore two types of cascading effects: domino effects create one-way dependencies, while hidden feedbacks produce two-way interactions; and compare them with the control case of driver sharing which can induce correlations. Using 30 regime shifts described as networks, we show that 45% of the pair-wise combinations of regime shifts present at least one plausible structural interdependence. Driver sharing is more common in aquatic systems, while hidden feedbacks are more commonly found in terrestrial and Earth systems tipping points. The likelihood of cascading effects depends on cross-scale interactions, but differs for each cascading effect type. Regime shifts should not be studied in isolation: instead, methods and data collection should account for potential teleconnections. -

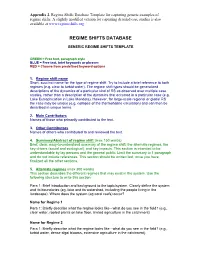

Regime Shifts Database Template for Capturing Generic Examples of Regime Shifts

Appendix 2. Regime Shifts Database Template for capturing generic examples of regime shifts. A slightly modified version for capturing detailed case studies is also available at www.regimeshifts.org. REGIME SHIFTS DATABASE GENERIC REGIME SHIFTS TEMPLATE GREEN = Free text, paragraph style BLUE = Free text, brief keywords or phrases RED = Choose from predefined keyword options 1. Regime shift name Short, succinct name for the type of regime shift. Try to include a brief reference to both regimes (e.g. clear to turbid water). The regime shift types should be generalized descriptions of the dynamics of a particular kind of RS as observed over multiple case studies, rather than a description of the dynamics that occurred in a particular case (e.g. Lake Eutrophication in Lake Mendota). However, for large-scale regional or global RS the case may be unique (e.g. collapse of the thermohaline circulation) and can then be described in unique terms. 2. Main Contributors Names of those who primarily contributed to the text. 3. Other Contributors Names of others who contributed to and reviewed the text. 4. Summary/Abstract of regime shift (max 150 words) Brief, clear, easy-to-understand summary of the regime shift: the alternate regimes, the key drivers (social and ecological), and key impacts. This section is intended to be understandable by lay persons and the general public. Limit the summary to 1 paragraph and do not include references. This section should be written last, once you have finalized all the other sections. 5. Alternate regimes (max 300 words) This section describes the different regimes that may exist in the system. -

Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute” Russian Antarctic Expedition

FEDERAL SERVICE OF RUSSIA FOR HYDROMETEOROLOGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING Federal State Budgetary Institution “Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute” Russian Antarctic Expedition QUARTERLY BULLETIN №4 (65) October - December 2013 STATE OF ANTARCTIC ENVIRONMENT Operational data of Russian Antarctic stations St. Petersburg 2014 FEDERAL SERVICE OF RUSSIA FOR HYDROMETEOROLOGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING Federal State Budgetary Institution “Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute” Russian Antarctic Expedition QUARTERLY BULLETIN №4 (65) October – December 2013 STATE OF ANTARCTIC ENVIRONMENT Operational data of Russian Antarctic stations Edited by V.V. Lukin St. Petersburg 2014 Editor-in-Chief M.O. Krichak (Russian Antarctic Expedition – RAE) Authors and contributors Section 1 M.O. Krichak (RAE), Section 2 Ye.I. Aleksandrov (Department of Sea-Air Interaction) Section 3 G.Ye. Ryabkov (Department of Ice Regime and Forecasting) Section 4 A.I. Korotkov (Department of Ice Regime and Forecasting) Section 5 Ye.Ye. Sibir (Department of Sea-Air Interaction) Section 6 I.V. Moskvin, Yu.G. Turbin (Department of Geophysics) Section 7 V.L. Martyanov (RAE) Translated by I.I. Solovieva http://www.aari.aq/, Antarctica/ Quarterly Bulletin/ Acknowledgements: Russian Antarctic Expedition is grateful to all AARI staff for participation and help in preparing this Bulletin. For more information about the contents of this publication, please, contact Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute of Roshydromet Russian Antarctic Expedition Bering St., 38, St. Petersburg 199397 Russia Phone: (812) 352 15 41; 337 31 04 Fax: (812) 337 31 86 E-mail: [email protected] CONTENTS PREFACE 1 1. DATA OF AEROMETEOROLOGICAL OBSERVATIONS AT THE RUSSIAN ANTARCTIC STATIONS 3 2. METEOROLOGICAL CONDITIONS IN OCTOBER-DECEMBER 2013 42 3. -

Frozen Desert Alive the Role of Sea Ice for Pelagic Macrofauna and Its Predators: Implications for the Antarctic Pack-Ice Food Web

Frozen Desert Alive The role of sea ice for pelagic macrofauna and its predators: implications for the Antarctic pack-ice food web Hauke Flores FrozenDesertAlive �-*#-$1#'!#$-0.#*%'!+!0-$3,,"'21.0#"2-01S '+.*'!2'-,1$-02&#,20!2'!.!)V'!#$--"5# 0',2#" 7-,1#,--'#, T4TQ""# "*#!20-,'!4#01'-,4'* *#2S &22.S 555T03%T,* ' *'-2&##) !2*-%' #12,"#, #*#).3 03% "'11#022'#1 ',"#6 %&'(S[YZV[RVXVXVVUU[VT 1%23&4(%5"1&%"%617(%(6"( FrozenDesertAlive �-*#-$1#'!#$-0.#*%'!+!0-$3,,"'21.0#"2-01S '+.*'!2'-,1$-02&#,20!2'!.!)V'!#$--"5# 17"8&9:1%8 2#04#0)0'(%',%4,"-!2-02',"# <'1)3,"##,(23305#2#,1!&..#, ,"#1'()13,'4#01'2#'260-,',%#, -.%#8%4,"# 1#!2-0>%,'$'!31Q"0T8T?5021Q ',-.#, 02#4#0"#"'%#,-. 40'("%S+#'TRR[ -+SUTSW330 "--0 HaukeFlores %# -0#,-.SZ1#.2#+ #0S[YV 2#'0#+#0&4#, 0-+-2-0 S0-$T"0T<T2T<-*$$ 9-.0-+-2-0 SB0T2TT4,80,#)#0 '#--0"#*',%1!-++'11'# S0-$T"0T'0T:T2T<T"#'0 S0-$T"0T4T5T'2&+,, S0-$T"0T8TT>T5-*!)#02 %,+#+-07-$+7%0,"+-2� %,6#"#,)#,,+#',#60-!+322#0 6'1#*8*-0#1 TV&#.TS[TSVTX2,TTRRZ Contents ",%*'1&13++07 Z B32!&13++07 SS 6#0+,13++07 SV 9&.2#0S 6#,#0*%,20-"3!2'-, S[ 9&.2#0T B'#2-$25-'!#$'1&1.#!'#1$0-+2&#&-32&&*," U[ %1*,"1,""*#.&,2%1*,"1QChampsocephalusgunnari ,"Chaenocephalusaceratus',TRRSTRRU PolarBiology27(2004)119R129 9&.2#0U ",#0%7!-,2#,2-$,20!2'!+#1-.#*%'!$'1S XS '+.*'!2'-,1$-02&#+0',#$--"5# PolarBiology29(2006)10451051 9&.2#0V B'120' 32'-,Q 3,",!#,"#!-*-%'!*0#*#4,!#-$ YU .#*%'!$'1',2P#4&#Q&-32�,7!#, MarineEcologyProgressSeries367(2008)271282 9&.2#0W -

'Regime Shift' Concept in Addressing Social-Ecological Change

Using the ‘regime shift’ concept in addressing social-ecological change Christian A. Kull*a, b Christoph Kuefferc,d David M. Richardsond Ana Sofia Vaze Joana R. Vicentee João Pradinho Honradoe This is an authors’ preprint version of the article published in the journal Geographical Research. The final, definitive version is available through Wiley’s Online Library at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1745-5871.12267/full Citation: Kull, C.A., Kueffer, C., Richardson, D.M., Vaz, A.S., Vicente, J.R., Honrado, J.P., (2017). Using the ‘regime shift’ concept in addressing social-ecological change. Geographical Research. 56 (1): 26-41. DOI: 10.1111/1745-5871.12267. *Corresponding author. [email protected] a Institute of Geography and Sustainability, University of Lausanne, Switzerland b Centre for Geography and Environmental Science, Monash University, Australia c Institute of Integrative Biology, Department of Environmental Systems Science, ETH Zurich, Switzerland d Centre for Invasion Biology, Department of Botany and Zoology, Stellenbosch University, South Africa e Research Network in Biodiversity and Evolutionary Biology (InBIO/CIBIO) & Faculty of Sciences, University of Porto, Portugal ABSTRACT ‘Regime shift’ has emerged as a key concept in the environmental sciences. The concept has roots in complexity science and its ecological applications and is increasingly applied to intertwined social and ecological phenomena. Yet, what exactly is a regime shift? We explore this question at three nested levels. First, we propose a broad, contingent, multi-perspective epistemological basis for the concept, seeking to build bridges between its complexity theory origins and critiques from science studies, political ecology, and environmental history. -

Microzooplankton Herbivory in the Ross Sea, Antarctica David A

Deep-Sea Research II 47 (2000) 3249}3272 Microzooplankton herbivory in the Ross Sea, Antarctica David A. Caron! * , Mark R. Dennett!, Darcy J. Lonsdale", Dawn M. Moran!, Ludmilla Shalapyonok! !Department of Biology, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA 02543, USA "Marine Sciences Research Center, State University of New York, Stony Brook, NY 11794-5000, USA Received 1 June 1999; received in revised form 15 September 1999; accepted 1 October 1999 Abstract Microplankton abundances and phytoplankton mortality rates were determined at six stations during four cruises spanning three seasons in the Ross Sea polynya, Antarctica (early spring, Oct.}Nov. 1996; mid-late summer, Jan.}Feb. 1997; fall, Apr. 1997; mid-late spring, Nov.}Dec. 1997). Rates of microzooplankton herbivory were measured using a modi"ed dilution technique, as well as by examining the rate of disappearance of phytoplankton (chlorophyll) in samples incubated in the dark (i.e. grazing in the absence of phytoplankton growth). Strong seasonal cycles of phytoplankton and microzooplankton abundance were observed during the study. Microzooplankton abundance varied by more than three orders of magnitude during the four cruises, and was positively correlated with phytoplankton biomass over the entire data set. Nevertheless, microzooplankton grazing was insu$cient to impact signi"cantly phytoplankton standing stocks during most of the experiments performed in this perenially cold environment. Only thirteen out of a total of 51 experiments yielded phytoplank- ton mortality rates that were signi"cantly di!erent from zero. The highest mortality rate observed in this study (0.26 d\) was modest compared with maximal rates that have been observed in temperate and tropical ecosystems.