Irish Women in Medicine, C.1880S-1920S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edit Summer 2007

60282_Edit_Summer07 2/5/07 02:01 Page 1 The University of Edinburgh INCLUDING BILLET & GENERAL COUNCIL PAPERS SUMMER 07 Zhong Nanshan honoured Zhong Nanshan, who first identified SARS, received an honorary degree at a ceremony celebrating Edinburgh’s Chinese links ALSO INSIDE Edinburgh is to play host to the first British centre for human and avian flu research, while the Reid Concert Hall Museum will house a unique clarinet collection 60282_Edit_Summer07 2/5/07 02:01 Page 2 60282_Edit_Summer07 2/5/07 09:35 Page 3 Contents 16xx Foreword Welcome to the Summer 2007 edition of Edit, and many thanks to everyone who contacted us with such positive feedback about our new design. A recent ceremony in Beijing celebrated the University’s links with China and saw Professor 18 Zhong Nanshan receiving an honorary degree; Edit takes a closer look at our connections – historical and present-day – to that country (page 14). The discovery of H5N1 on a turkey farm in Norfolk earlier this year meant avian flu once 14 20 again became headline news. Robert Tomlinson reports on plans to establish a cutting-edge centre at the University to research the virus Features (page 16). The focus of our third feature is the Shackleton 14 Past, Present and Future Bequest, an amazing collection of clarinets Developing links between China and Edinburgh. recently bequeathed to the University that will be housed in the Reid Concert Hall Museum 16 From Headline to Laboratory (page 20). Edinburgh takes lead in Britain’s fight against avian flu. Anne Borthwick 20 Art meets Science Editor The remarkable musical legacy of the paleoclimatologist Editor who championed the clarinet. -

The Womanly Physician in Doctor Zay and Mona Maclean, Medical Student

25 영어영문학연구 제45권 제3호 Studies in English Language & Literature (2019) 가을 25-40 http://dx.doi.org/10.21559/aellk.2019.45.3.002 The Womanly Physician in Doctor Zay and Mona Maclean, Medical Student Ji-Eun Kim (Yonsei University) Kim, Ji-Eun. “The Womanly Physician in Doctor Zay and Mona Maclean, Medical Student.” Studies in English Language & Literature 45.3 (2019): 25-40. This paper investigates the representation of women physicians in two novels - an American novel titled Elizabeth Stuart Phelps’s Doctor Zay (1882), and a British novel, Dr. Margaret Todd’s Mona Maclean, Medical Student (1892). While also looking at differences these individual novels have, this paper aims to look at how these transatlantic nineteenth century novels have common threads of linking women doctors with the followings: the constant referral to “womanliness,” the question of class affiliations, marriage, and medical modernity. While the two doctor novels end with the conventional marriage plot, these novels fundamentally questioned the assumption that women doctors could only cure women and children. These texts also tried to bend existing gender roles and portrayed women doctors who were deemed as “womanly.” (Yonsei University) Key Words: Doctor Zay, Mona Maclean Medical Student, woman doctors, womanliness, nineteenth-century I. Introduction What common ground do Dr. Quinn of “Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman” (1993-98), Dana Scully in “The X-Files” (1993-2002), Meredith Gray, Miranda Bailey and Christina Yang in “Grey’s Anatomy” (since 2005) have? These prime-time U.S. TV dramas depict impressive women physicians successively juggling their medical 26 Ji-Eun Kim careers, tough responsibilities and hectic personal lives. -

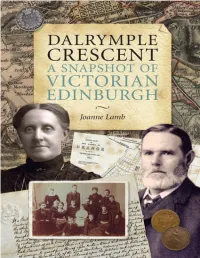

Dalrymple Crescent a Snapshot of Victorian Edinburgh

DALRYMPLE CRESCENT A SNAPSHOT OF VICTORIAN EDINBURGH Joanne Lamb ABOUT THE BOOK A cross-section of life in Edinburgh in the 19th century: This book focuses on a street - Dalrymple Crescent - during that fascinating time. Built in the middle of the 19th century, in this one street came to live eminent men in the field of medicine, science and academia, prosperous merchants and lawyers, The Church, which played such a dominant role in lives of the Victorians, was also well represented. Here were large families and single bachelors, marriages, births and deaths, and tragedies - including murder and bankruptcy. Some residents were drawn to the capital by its booming prosperity from all parts of Scotland, while others reflected the Scottish Diaspora. This book tells the story of the building of the Crescent, and of the people who lived there; and puts it in the context of Edinburgh in the latter half of the 19th century COPYRIGHT First published in 2011 by T & J LAMB, 9 Dalrymple Crescent, Edinburgh EH9 2NU www.dcedin.co.uk This digital edition published in 2020 Text copyright © Joanne Lamb 2011 Foreword copyright © Lord Cullen 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-0-9566713-0-1 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Designed and typeset by Mark Blackadder The publisher acknowledges a grant from THE GRANGE ASSOCIATION towards the publication of this book THIS DIGITAL EDITION Ten years ago I was completing the printed version of this book. -

Undergraduate Guide 2021 the University of Edinburgh I

Undergraduate Guide 2021 The University of Edinburgh i Undergraduate Guide 2021 www.ed.ac.uk 01 We’re consistently ranked one of the top 50 universities in the Top th world. We’re 20 in “ You are now in a place where the best the 2020 QS World courses upon earth are within your 50 University Rankings. reach… such an opportunity you will never again have.” Thomas Jefferson ND TH American Founding Father and President, speaking to his son-in-law Thomas Mann Randolph as he began 2 4 his studies here in 1786 Edinburgh is ranked We’re ranked the second best fourth in the UK student city in for research power, the UK and 7th based on the 2014 in Europe.* Research Excellence Framework.† £10m Our students accessed undergraduate financial support totalling more than £10 million in 2018/19. Top 19 TH We're ranked 19th in the world's most international 10 universities‡. Since We’re ranked in the 2010, we have taught top 10 in the UK students from 160 and in the top 100 countries. in the world for the employability of our graduates.§ * QS Best Student Cities 2019 † Times Higher Education, Overall Ranking of Institutions § Times Higher Education, Global Employability University Ranking 2019 ‡ Times Higher Education, The World's Most International Universities 2020 02 www.ed.ac.uk/undergraduate/degrees Undergraduate Guide 2021 The University of Edinburgh 03 Open to a world of possibilities We live in a complex, fast-changing world and we’re honest about the significant challenges facing us all. As a leading global university, we know education will play a vital role solving those challenges and relish our shared responsibility to respond to them. -

Objects Linked to Women's Suffrage in Moad's Collection

Background Information – objects linked to Women’s Suffrage in MoAD’s collection The issue of female suffrage was one of the major unresolved questions in western democracies in the early decades of the twentieth century. Many activists looked to Australia as the exemplar of progressive democratic leadership, because Australian women had won both the vote and the right to stand for parliament at a national level in 1903. Australians were also active in suffrage campaigns overseas, particularly in the United Kingdom, in the years just prior to the First World War. The formation of the Women s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1903 marked a break from the politics of demure persuasion that characterised the earlier period of the suffrage campaign. Frustrated at the lack of progress from years of moderate speeches and promises about women's suffrage from members of parliament, Emmeline Pankhurst, founder of the WSPU,and several colleagues decided to abandon these patient tactics in favour of more militant ones. Emmeline later wrote that Deeds, not words, was to be our permanent motto. (E. Pankhurst, My Own Story, 1914, p.38). Over several years the actions of WPSU members became increasingly physical and violent. Emmeline herself was jailed several times for her actions, the first time in 1908 when she tried to enter Parliament to deliver a protest resolution to Prime Minister Asquith. She spoke out against the conditions of her first incarceration, protesting at the tiny amounts of food she received, the vermin, and the hardship of solitary confinement. In 1908 two WSPU members, Edith New and Mary Leigy, threw rocks at the windows of the Prime Minister s home at 10 Downing Street. -

A Study of the Women's Suffrage Movement in Nineteenth-Century English Periodical Literature

PRINT AND PROTEST: A STUDY OF THE WOMEN'S SUFFRAGE MOVEMENT IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH PERIODICAL LITERATURE Bonnie Ann Schmidt B.A., University College of the Fraser Valley, 2004 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREEE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of History 43 Bonnie Ann Schmidt 2005 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fa11 2005 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Bonnie Ann Schmidt Degree: Master of Arts Title: Print and Protest: A Study of the Women's Suffrage Movement in Nineteenth-Century English Periodical Literature Examining Committee: Dr. Ian Dyck Senior Supervisor Associate Professor of History Dr. Mary Lynn Stewart Supervisor Professor of Women's Studies Dr. Betty A. Schellenberg External Examiner Associate Professor of English Date Defended: NOV.s/15 SIMON FRASER UN~VER~~brary DECLARATION OF PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection, and, without changing the content, to translate the thesislproject or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

Women in Britain. Voices and Perspective from Twentieth Century History

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 21 Issue 1 Article 33 February 2020 Book Review: Women in Britain. Voices and perspective from twentieth century history Shivani Singh Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Singh, Shivani (2020). Book Review: Women in Britain. Voices and perspective from twentieth century history. Journal of International Women's Studies, 21(1), 412-417. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol21/iss1/33 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2020 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Reviewer’s name: Shivani Singh Academic degree: Ph.D. Title: Dr.; Assistant Professor Contact details: B.A. Liberal Arts, Inter-Disciplinary School of Science, IUCAA road, Savitribai Phule Pune University, Ganeshkhind, Pune, Maharashtra, India. Pincode: 411007. Phone number: 9503532176; email: [email protected] Information about the reviewed book: Book Title: Women in Britain. Voices and perspective from twentieth century history. Author: Janet H. Howarth Publication Year: 2019 Publisher: I. B. Tauris & Co. Ltd. City: London, Great Britain Total number of pages: 320 Illustrations: None Photographs: 15 (listed after contents) Appendix, or index: Included as Index of Persons and Subject Index at the end. Price: $2256 Paperback 412 Journal of International Women’s Studies Vol. -

Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women: Autobiographical Sketches by Elizabeth Blackwell Elizabeth Blackwell

History Books History 2006 Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women: Autobiographical Sketches by Elizabeth Blackwell Elizabeth Blackwell Amy Bix Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/history_books Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Blackwell, Elizabeth and Bix, Amy, "Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women: Autobiographical Sketches by Elizabeth Blackwell" (2006). History Books. 8. http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/history_books/8 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the History at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Books by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I f f INTRODUCTION i i I by Amy Sue Bix f I t I The history of women as healers dates back many cen- t turies, long before the life of Elizabeth Blackwell. We have evidence of women as healers and midwives in ancient Greece; for example, some women have funeral inscriptions describing them with the terms "midwife" and "physician." Women's practice of medicine was not universally welcomed; in Athens during the fourth century BCE, female healers were apparently accused of performing illegal abortions and banned from the profession. Stories suggest that one of the era's most famous medical women, Agnodice, had to cut her hair and dress in men's clothing to attend physicians' classes, since her practice of medicine was illegal. -

Better for Women

Better for women Improving the health and wellbeing of girls and women December 2019 1 Within this document we use the terms woman and women’s health. However, it is important to acknowledge that it is not only people who identify as women for whom it is necessary to access women’s health and Contents reproductive services in order to maintain their gynaecological health and reproductive wellbeing. Gynaecological and obstetric services and delivery of care must therefore be appropriate, inclusive and sensitive to the needs of Foreword 4 - 5 those individuals whose gender identity does not align with the sex they were assigned at birth. Executive summary and recommendations 6 - 25 Chapter 1: A life course approach 26 - 35 Chapter 2: ‘What women are saying’ 36 - 47 Chapter 3: Access to accurate education and information 48 - 73 Introduction The importance of education The need for accurate information Overcoming stigmas RCOG recommendations Chapter 4: Prevention and empowerment 74 - 123 Introduction Preventing unplanned pregnancies Health indicators before, during and after pregnancy Safeguarding vulnerable girls and women Gynaecological cancers – prevention and early diagnosis General health during and after the menopause RCOG recommendations Chapter 5: Fragmentation and access to services 124 - 161 Introduction Commissioning Access to contraception Access to cervical screening Access to abortion services Access to appropriate fertility care RCOG recommendations Conclusion 162 - 163 2 3 for longer in the post reproductive era than they spent in their reproductive phase. Their expectation is to have Foreword quality of life as well as longevity. They are looking to us to help them achieve this. -

1 'A Glass Half Full'? Women's History in the UK June Purvis, University Of

‘A glass half full’? Women’s history in the UK June Purvis, University of Portsmouth in Karen M. Offen, University of Stanford, USA and Chen Yan, Fudan University, China, Women’s History at the Cutting Edge, Special Issue of Women’s History Review forthcoming 2017/early 2018 ABSTRACT This article offers an overview of the development of women’s history in the UK over the last twenty years or so. It is noted that over this period women’s history has expanded massively, an expansion that has cut across national boundaries and drawn in scholars from other disciplines than History. Seven themes in women’s history are identified as being prominent during this time – a focus on the modern period (post 1780), a strong empirical bent, a questioning of the dominance of a separate spheres discourse, an interest in life stories and biographies, an interest in the women’s suffrage movement, a ‘religious turn’ and a ‘transnational turn’. BIOGRAPHICAL DETAILS June Purvis is Emeritus Professor of Women’s and Gender History at the University of Portsmouth, UK. She has published extensively on women’s education in nineteenth-century England and on the suffragette movement in Edwardian Britain. Her publications include Emmeline Pankhurst: a biography (2002: Routledge) and Women’s Activism: global perspectives from the 1890s to the present (2013: Routledge), co-edited with Francisca de Haan, Margaret Allen and Krassimira Daskalova. June is the Founding and Managing Editor of Women’s History Review and also the Editor for a book series with Routledge on Women’s and Gender History. She is Chair of the Women’s History Network (2014-18) and Secretary and Treasurer of the International Federation for Research in Women’s History (2015-20). -

The Fashioning of Orientalism in the Travelogues of 18Th-Century British

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Middle Eastern Communities and Migrations Undergraduate Research Student Research Paper Series Summer 2017 Significant Others: The aF shioning of Orientalism in the Travelogues of 18th-Century British Women Rachel Barton James Madison University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.lib.jmu.edu/mecmsrps Part of the Islamic World and Near East History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Barton, Rachel, "Significant Others: The ashioninF g of Orientalism in the Travelogues of 18th-Century British Women" (2017). Middle Eastern Communities and Migrations Student Research Paper Series. 4. http://commons.lib.jmu.edu/mecmsrps/4 This Presented Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Middle Eastern Communities and Migrations Student Research Paper Series by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Significant Others: The Fashioning of Orientalism in the Travelogues of 18th-Century British Women Rachel Barton June 2017 1 British fascination with the Ottoman Empire was not a new phenomenon in the 18th Century. To the Occident, the Orient had always been a source of mystery, intrigue, and romance. Regardless of whether the desire for knowledge of the unknown Other came from colonial interest or a sense of scientific and anthropologic duty, travelers to the empire filled their journals and letters with observations of all aspects of Ottoman life. These crossers of cultural boundaries were self-proclaimed experts on the economic, political, and social institutions of the East, and wrote with confidence for themselves and readers back home. -

Women's Suffrage Movement in Britain: the Long Road Toward

PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ALGERIA Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research University of Tlemcen Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of English Women’s Suffrage Movement in Britain: The Long Road toward Women’s Rights (1850/1928) Dissertation submitted to the Department of English as a partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Literature and Civilisation Presented by: Supervised by: KECHE Houda Dr. SENOUCI Faiza MAMMERI Chahinaz BOARD OF EXAMINERS: Dr/ KHELLADI Mohamed Chairperson Dr/ SENOUCI Faiza Supervisor Mrs/SEBBOUI Khadidja Examiner Academic Year: 2016-2017 Acknowledgements Before all we thank almighty God for blessing us in achieving this work. All the thanks go to our supervisor Dr. SENOUCI Faiza who has guided us with great professionalism and whose guidance and suggestion have helped us a lot in the fulfilment of this research work. I also welcome this opportunity to express my appreciation to the members of jury and to all the teachers of the department of English, from whom we have learnt a lot Million thanks to all who helped us in this work II Dedication I dedicate this modest work: To my lovely mother Chafia. And to the best man on earth in my eyes my father Mokhtar There is no doubt in my mind that without them I would never go further in my life, and I say to them: “Thank you for your affection, prayers and your selfless sacrifices.” To my shining beloved sister Hanane To the best copy of mine Amira To my lovely brothers Walid and Haythem To all my family, especially Zahra, Hadjer, Sara, Meriem To my friend who shared this work with me: Chahinaz To all my best friends Houda III Dedication I dedicate this humble work: To my wonderful deeply missed mother, I will always keep you in my thoughts and prayers.