Depictions of Colonial Macao in 1950S' Hollywood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

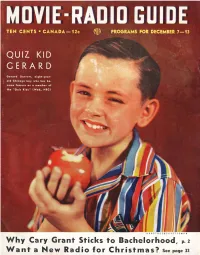

MOVIE · RADIO GUIDE: the National Weekly of Personalities and Programs

Why Cary Grant Sticks to Bachelorhood, p.2 Wan taN e vi R a d i 0 for C h r i s t 111 as? See page 33 MOVIE · RADIO GUIDE: The National Weekly of Personalities and Programs This Is Indeed the Golden .Age of Music WE A RE indebted to Viva liebling, our mu sic to find new songs and develop new song-writers editor, for call ing our attention to th e un and make new arrangements of all t he old tu nes pa ra lleled number of fine music programs now for which the copyrights had expired. All thar avai lable to listeners. O ne look at our renewed 8MI has b83n doi ng very success ful ly. " March of Music" departmen+ is abundant con Vv'h6t may happen soon is this : O n J anuary firm ation . Turn to page 14 noV! and see fOi I 'ihe networks may throw all ASCAP music off yo ursel f. the air. Th e networks want to pay for AS CAP Those names may mean little as yet, but read music by t he piece-so mu ch fo r every t i me it them through. The Cincinnati Symphony offers is used-which sounds fa ir enough to us. ASCAP "The Swan of Tuonela," "The Marriage of Fig wants a lump sum, a percentage of a ll t he money aro" comes from the Metropolitan Opera Com t,"lken in by a radio station . Righ t now, ASCAP pany, the NBC Symphony offers an all-Sibelius and the broadcasters aren't speaking. -

Role of the Archives in the Future

… You can fool all the people some of the time, and some of the people all the time, but you cannot fool all the people all the time…” Abraham Lincoln ( 1809 – 1865 ) FACTS AND FICTION- ARCHIVAL FOOTAGE HISTORICAL EVENTS AND TELEVISION AND FILM PRODUCTIONS Media Archeology Movies and television productions are released and transmitted each year dealing with historical events or public personalities like politicians , military leaders, revolutionaries, and people with a record of special achievemments. The aim of my presentation is to make you aware of different possibilities in reusing archival footage in movies. It is my intention to inform you about the importance of the audiovisual archives and how to reuse transmitted programmes or real shots of life in new productions. It is not my intention to evaluate real shots in historical movies and to report about facts and fiction in those films. The subject is dealt with in the book called: PAST IMPERFECT. History According to the Movies. 1995, and my own paper on the same subject: HISTORY AND MOVIES: An evaluation of the information of historical events, of international known personalities and of famous sites and buildings describes in movies. External links: ( Contact: http://www.baacouncil.org/ or [email protected] for copy of the paper) Television companies should be proud of their collections of transmitted programmes. Because I have worked for televison archive for about 29 years I have viewed a lot of television programmes and movies. Some years ago I started to question the reuse of transmitted television programmes and also the active reuse of news in new productions. -

The File on Robert Siodmak in Hollywood: 1941-1951

The File on Robert Siodmak in Hollywood: 1941-1951 by J. Greco ISBN: 1-58112-081-8 DISSERTATION.COM 1999 Copyright © 1999 Joseph Greco All rights reserved. ISBN: 1-58112-081-8 Dissertation.com USA • 1999 www.dissertation.com/library/1120818a.htm TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION PRONOUNCED SEE-ODD-MACK ______________________ 4 CHAPTER ONE GETTING YOUR OWN WAY IN HOLLYWOOD __________ 7 CHAPTER TWO I NEVER PROMISE THEM A GOOD PICTURE ...ONLY A BETTER ONE THAN THEY EXPECTED ______ 25 CHRISTMAS HOLIDAY _____________________________ 25 THE SUSPECT _____________________________________ 49 THE STRANGE AFFAIR OF UNCLE HARRY ___________ 59 THE SPIRAL STAIRCASE ___________________________ 74 THE KILLERS _____________________________________ 86 CRY OF THE CITY_________________________________ 100 CRISS CROSS _____________________________________ 116 THE FILE ON THELMA JORDON ___________________ 132 CHAPTER THREE HOLLYWOOD? A SORT OF ANARCHY _______________ 162 AFTERWORD THE FILE ON ROBERT SIODMAK___________________ 179 THE COMPLETE ROBERT SIODMAK FILMOGRAPHY_ 185 BIBLIOGRAPHY __________________________________ 214 iii INTRODUCTION PRONOUNCED SEE-ODD-MACK Making a film is a matter of cooperation. If you look at the final credits, which nobody reads except for insiders, then you are surprised to see how many colleagues you had who took care of all the details. Everyone says, ‘I made the film’ and doesn’t realize that in the case of a success all branches of film making contributed to it. The director, of course, has everything under control. —Robert Siodmak, November 1971 A book on Robert Siodmak needs an introduction. Although he worked ten years in Hollywood, 1941 to 1951, and made 23 movies, many of them widely popular thrillers and crime melo- dramas, which critics today regard as classics of film noir, his name never became etched into the collective consciousness. -

Men-On-The-Spot and the Allied Intervention in the Russian Civil War, 1917-1920 Undergraduate

A Highly Disreputable Enterprise: Men-on-the-Spot and the Allied Intervention in the Russian Civil War, 1917-1920 Undergraduate Research Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for graduation "with Honors Research Distinction in History" in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Conrad Allen The Ohio State University May 2016 Project Advisor: Professor Jennifer Siegel, Department of History The First World War ended on November 11, 1918. The guns that had battered away at each other in France and Belgium for four long years finally fell silent at eleven A.M. as the signed armistice went into effect. "There came a second of expectant silence, and then a curious rippling sound, which observers far behind the front likened to the noise of a light wind. It was the sound of men cheering from the Vosges to the sea," recorded South African soldier John Buchan, as victorious Allied troops went wild with celebration. "No sleep all night," wrote Harry Truman, then an artillery officer on the Western Front, "The infantry fired Very pistols, sent up all the flares they could lay their hands on, fired rifles, pistols, whatever else would make noise, all night long."1 They celebrated their victory, and the fact that they had survived the worst war of attrition the world had ever seen. "I've lived through the war!" cheered an airman in the mess hall of ace pilot Eddie Rickenbacker's American fighter squadron. "We won't be shot at any more!"2 But all was not quiet on every front. -

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: from Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare By

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: From Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare by Matthew A. Bellamy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2018 Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Najita, Chair Professor Daniel Hack Professor Mika Lavaque-Manty Associate Professor Andrea Zemgulys Matthew A. Bellamy [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-6914-8116 © Matthew A. Bellamy 2018 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to all my students, from those in Jacksonville, Florida to those in Port-au-Prince, Haiti and Ann Arbor, Michigan. It is also dedicated to the friends and mentors who have been with me over the seven years of my graduate career. Especially to Charity and Charisse. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication ii List of Figures v Abstract vi Chapter 1 Introduction: Espionage as the Loss of Agency 1 Methodology; or, Why Study Spy Fiction? 3 A Brief Overview of the Entwined Histories of Espionage as a Practice and Espionage as a Cultural Product 20 Chapter Outline: Chapters 2 and 3 31 Chapter Outline: Chapters 4, 5 and 6 40 Chapter 2 The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 1: Conspiracy, Bureaucracy and the Espionage Mindset 52 The SPECTRE of the Many-Headed HYDRA: Conspiracy and the Public’s Experience of Spy Agencies 64 Writing in the Machine: Bureaucracy and Espionage 86 Chapter 3: The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 2: Cruelty and Technophilia -

George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf5s2006kz No online items George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042 Finding aid prepared by Hilda Bohem; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 November 2. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections George P. Johnson Negro Film LSC.1042 1 Collection LSC.1042 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: George P. Johnson Negro Film collection Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1042 Physical Description: 35.5 Linear Feet(71 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1916-1977 Abstract: George Perry Johnson (1885-1977) was a writer, producer, and distributor for the Lincoln Motion Picture Company (1916-23). After the company closed, he established and ran the Pacific Coast News Bureau for the dissemination of Negro news of national importance (1923-27). He started the Negro in film collection about the time he started working for Lincoln. The collection consists of newspaper clippings, photographs, publicity material, posters, correspondence, and business records related to early Black film companies, Black films, films with Black casts, and Black musicians, sports figures and entertainers. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: English . Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Portions of this collection are available on microfilm (12 reels) in UCLA Library Special Collections. -

Complete Film Noir

COMPLETE FILM NOIR (1940 thru 1965) Page 1 of 18 CONSENSUS FILM NOIR (1940 thru 1959) (1960-1965) dThe idea for a COMPLETE FILM NOIR LIST came to me when I realized that I was “wearing out” a then recently purchased copy of the Film Noir Encyclopedia, 3rd edition. My initial plan was to make just a list of the titles listed in this reference so I could better plan my film noir viewing on AMC (American Movie Classics). Realizing that this plan was going to take some keyboard time, I thought of doing a search on the Internet Movie DataBase (here after referred to as the IMDB). By using the extended search with selected criteria, I could produce a list for importing to a text editor. Since that initial list was compiled almost twenty years ago, I have added additional reference sources, marked titles released on NTSC laserdisc and NTSC Region 1 DVD formats. When a close friend complained about the length of the list as it passed 600 titles, the idea of producing a subset list of CONSENSUS FILM NOIR was born. Several years ago, a DVD producer wrote me as follows: “I'd caution you not to put too much faith in the film noir guides, since it's not as if there's some Film Noir Licensing Board that reviews films and hands out Certificates of Authenticity. The authors of those books are just people, limited by their own knowledge of and access to films for review, so guidebooks on noir are naturally weighted towards the more readily available studio pictures, like Double Indemnity or Kiss Me Deadly or The Big Sleep, since the many low-budget B noirs from indie producers or overseas have mostly fallen into obscurity.” There is truth in what the producer says, but if writers of (film noir) guides haven’t seen the films, what chance does an ordinary enthusiast have. -

Directory of Theamerican Society of Certified Public Accountants, January 1, 1925 American Society of Certified Public Accountants

University of Mississippi eGrove American Institute of Certified Public Accountants AICPA Committees (AICPA) Historical Collection 1-1-1925 Directory of theAmerican Society of Certified Public Accountants, January 1, 1925 American Society of Certified Public Accountants Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aicpa_comm Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation American Society of Certified Public Accountants, "Directory of theAmerican Society of Certified Public Accountants, January 1, 1925" (1925). AICPA Committees. 134. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aicpa_comm/134 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) Historical Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in AICPA Committees by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DIRECTORY The American Society of Certified Public Accountants Officers .. Directors .. Auditors State Representatives .. Membership Roster Constitution and By-Laws American Society of Certified Public Accountants JANUARY 1, 1925 421 Woodward Building Washington, D. C DIRECTORY sf The American Society of Certified Public Accountants Officers - Directors Auditors State Representatives .. Membership Roster Constitution and By-Laws AmericanThe Society of Certified Public Accountants Woodward Building Washington, D. C. JANUARY 1, 1925 CONTENTS Page Officers............ ................ 1......................... ............................................................. -

Angel Sings the Blues: Josef Von Sternberg's the Blue Angel in Context

FILMHISTORIA Online Vol. 30, núm. 2 (2020) · ISSN: 2014-668X REVIEW ESSAYS . Angel Sings the Blues: Josef von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel in Context ROBERT J. CARDULLO University of Michigan Abstract This essay reconsiders The Blue Angel (1930) not only in light of its 2001 restoration, but also in light of the following: the careers of Josef von Sternberg, Emil Jannings, and Marlene Dietrich; the 1905 novel by Heinrich Mann from which The Blue Angel was adapted; early sound cinema; and the cultural-historical circumstances out of which the film arose. In The Blue Angel, Dietrich, in particular, found the vehicle by which she could achieve global stardom, and Sternberg—a volatile man of mystery and contradiction, stubbornness and secretiveness, pride and even arrogance—for the first time found a subject on which he could focus his prodigious talent. Keywords: The Blue Angel, Josef von Sternberg, Emil Jannings, Marlene Dietrich, Heinrich Mann, Nazism. Resumen Este ensayo reconsidera El ángel azul (1930) no solo a la luz de su restauración de 2001, sino también a la luz de lo siguiente: las carreras de Josef von Sternberg, Emil Jannings y Marlene Dietrich; la novela de 1905 de Heinrich Mann de la cual se adaptó El ángel azul; cine de sonido temprano; y las circunstancias histórico-culturales de las cuales surgió la película. En El ángel azul, Dietrich, en particular, encontró el vehículo por el cual podía alcanzar el estrellato global, y Sternberg, un hombre volátil de misterio y contradicción, terquedad y secretismo, orgullo e incluso arrogancia, por primera vez encontró un tema en el que podía enfocar su prodigioso talento. -

The Culture of Queers

THE CULTURE OF QUEERS For around a hundred years up to the Stonewall riots, the word for gay men was ‘queers’. From screaming queens to sensitive vampires and sad young men, and from pulp novels and pornography to the films of Fassbinder, The Culture of Queers explores the history of queer arts and media. Richard Dyer traces the contours of queer culture, examining the differ- ences and continuities with the gay culture which succeeded it. Opening with a discussion of the very concept of ‘queers’, he asks what it means to speak of a sexual grouping having a culture and addresses issues such as gay attitudes to women and the notion of camp. Dyer explores a range of queer culture, from key topics such as fashion and vampires to genres like film noir and the heritage film, and stars such as Charles Hawtrey (outrageous star of the Carry On films) and Rock Hudson. Offering a grounded historical approach to the cultural implications of queerness, The Culture of Queers both insists on the negative cultural con- sequences of the oppression of homosexual men and offers a celebration of queer resistance. Richard Dyer is Professor of Film Studies at The University of Warwick. He is the author of Stars (1979), Now You See It: Studies in Lesbian and Gay Film (Routledge 1990), The Matter of Images (Routledge 1993) and White (Routledge 1997). THE CULTURE OF QUEERS Richard Dyer London and New York First published 2002 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor and Francis e-Library, 2005. -

Film Noir Classics -- Movie Posters 1948-1950

FILM NOIR CLASSICS -- MOVIE POSTERS 1948-1950 The distinctive style of movies of the golden age of Film Noir, the genre of Hollywood crime dramas distinguished by liberal doses of sex and cynicism, is captured in the striking graphics of these classic movie posters. The portrait that emerges of a darker side of mid-twentieth century America makes them a compelling resource for the study of that period as well as for film history archives. The light-hearted Gary Cooper / Barbara Stanwyck comedy “Ball of Fire” of 1941 that we include at the end of this listing drives home this contrast…but no matter what, somebody is going to get burned… Clicking on the item picture will take you to our website for ordering via our secure online system. We hope that you will enjoy this selection. Elisabeth Burdon & Craig Clinton ____________________________________________________ Backfire. Warner Bros. Hollywood. 1948 - 1950. One-sheet color silk-screen poster, 40 x 30 inches, for the 1950 Warner Brothers production "Backfire" directed by Vincent Sherman and starring Gordon MacRae, Edmond O’Brien, and Virginia Mayo (the film was completed in late 1948 but not released until 1950). The poster, a scarce item and in very good condition, was produced by Western Poster Company, San Francisco. "Backfire," a complicated drama involving numerous flashbacks, concerns a World War II veteran Bob Corey (MacRae), a nurse he meets while hospitalized, Julie Benson (Mayo), and Corey's good friend Steve Connolly (O'Brien). After considerable mayhem as the drama unfolds, including a near fatal attempt on Connolly's life, the film delivers a happy ending with the trio heading for Bob and Julie's new ranch.