The Meloidae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Topic Paper Chilterns Beechwoods

. O O o . 0 O . 0 . O Shoping growth in Docorum Appendices for Topic Paper for the Chilterns Beechwoods SAC A summary/overview of available evidence BOROUGH Dacorum Local Plan (2020-2038) Emerging Strategy for Growth COUNCIL November 2020 Appendices Natural England reports 5 Chilterns Beechwoods Special Area of Conservation 6 Appendix 1: Citation for Chilterns Beechwoods Special Area of Conservation (SAC) 7 Appendix 2: Chilterns Beechwoods SAC Features Matrix 9 Appendix 3: European Site Conservation Objectives for Chilterns Beechwoods Special Area of Conservation Site Code: UK0012724 11 Appendix 4: Site Improvement Plan for Chilterns Beechwoods SAC, 2015 13 Ashridge Commons and Woods SSSI 27 Appendix 5: Ashridge Commons and Woods SSSI citation 28 Appendix 6: Condition summary from Natural England’s website for Ashridge Commons and Woods SSSI 31 Appendix 7: Condition Assessment from Natural England’s website for Ashridge Commons and Woods SSSI 33 Appendix 8: Operations likely to damage the special interest features at Ashridge Commons and Woods, SSSI, Hertfordshire/Buckinghamshire 38 Appendix 9: Views About Management: A statement of English Nature’s views about the management of Ashridge Commons and Woods Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), 2003 40 Tring Woodlands SSSI 44 Appendix 10: Tring Woodlands SSSI citation 45 Appendix 11: Condition summary from Natural England’s website for Tring Woodlands SSSI 48 Appendix 12: Condition Assessment from Natural England’s website for Tring Woodlands SSSI 51 Appendix 13: Operations likely to damage the special interest features at Tring Woodlands SSSI 53 Appendix 14: Views About Management: A statement of English Nature’s views about the management of Tring Woodlands Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), 2003. -

Elytra Reduction May Affect the Evolution of Beetle Hind Wings

Zoomorphology https://doi.org/10.1007/s00435-017-0388-1 ORIGINAL PAPER Elytra reduction may affect the evolution of beetle hind wings Jakub Goczał1 · Robert Rossa1 · Adam Tofilski2 Received: 21 July 2017 / Revised: 31 October 2017 / Accepted: 14 November 2017 © The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Beetles are one of the largest and most diverse groups of animals in the world. Conversion of forewings into hardened shields is perceived as a key adaptation that has greatly supported the evolutionary success of this taxa. Beetle elytra play an essential role: they minimize the influence of unfavorable external factors and protect insects against predators. Therefore, it is particularly interesting why some beetles have reduced their shields. This rare phenomenon is called brachelytry and its evolution and implications remain largely unexplored. In this paper, we focused on rare group of brachelytrous beetles with exposed hind wings. We have investigated whether the elytra loss in different beetle taxa is accompanied with the hind wing shape modification, and whether these changes are similar among unrelated beetle taxa. We found that hind wings shape differ markedly between related brachelytrous and macroelytrous beetles. Moreover, we revealed that modifications of hind wings have followed similar patterns and resulted in homoplasy in this trait among some unrelated groups of wing-exposed brachelytrous beetles. Our results suggest that elytra reduction may affect the evolution of beetle hind wings. Keywords Beetle · Elytra · Evolution · Wings · Homoplasy · Brachelytry Introduction same mechanism determines wing modification in all other insects, including beetles. However, recent studies have The Coleoptera order encompasses almost the quarter of all provided evidence that formation of elytra in beetles is less currently known animal species (Grimaldi and Engel 2005; affected by Hox gene than previously expected (Tomoyasu Hunt et al. -

The Beetle Fauna of Dominica, Lesser Antilles (Insecta: Coleoptera): Diversity and Distribution

INSECTA MUNDI, Vol. 20, No. 3-4, September-December, 2006 165 The beetle fauna of Dominica, Lesser Antilles (Insecta: Coleoptera): Diversity and distribution Stewart B. Peck Department of Biology, Carleton University, 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K1S 5B6, Canada stewart_peck@carleton. ca Abstract. The beetle fauna of the island of Dominica is summarized. It is presently known to contain 269 genera, and 361 species (in 42 families), of which 347 are named at a species level. Of these, 62 species are endemic to the island. The other naturally occurring species number 262, and another 23 species are of such wide distribution that they have probably been accidentally introduced and distributed, at least in part, by human activities. Undoubtedly, the actual numbers of species on Dominica are many times higher than now reported. This highlights the poor level of knowledge of the beetles of Dominica and the Lesser Antilles in general. Of the species known to occur elsewhere, the largest numbers are shared with neighboring Guadeloupe (201), and then with South America (126), Puerto Rico (113), Cuba (107), and Mexico-Central America (108). The Antillean island chain probably represents the main avenue of natural overwater dispersal via intermediate stepping-stone islands. The distributional patterns of the species shared with Dominica and elsewhere in the Caribbean suggest stages in a dynamic taxon cycle of species origin, range expansion, distribution contraction, and re-speciation. Introduction windward (eastern) side (with an average of 250 mm of rain annually). Rainfall is heavy and varies season- The islands of the West Indies are increasingly ally, with the dry season from mid-January to mid- recognized as a hotspot for species biodiversity June and the rainy season from mid-June to mid- (Myers et al. -

Zoological Philosophy

ZOOLOGICAL PHILOSOPHY AN EXPOSITION WITH REGARD TO THE NATURAL HISTORY OF ANIMALS THE DIVERSITY OF THEIR ORGANISATION AND THE FACULTIES WHICH THEY DERIVE FROM IT; THE PHYSICAL CAUSES WHICH MAINTAIN LIFE WITHIr-i THEM AND GIVE RISE TO THEIR VARIOUS MOVEMENTS; LASTLY, THOSE WHICH PRODUCE FEELING AND INTELLIGENCE IN SOME AMONG THEM ;/:vVVNu. BY y;..~~ .9 I J. B. LAMARCK MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED LONDON' BOMBAY' CALCUTTA MELBOURNE THE MACMILLAN COMPANY TRANSLATED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION, BY NEW YORK • BOSTON . CHICAGO DALLAS • SAN FRANCISCO HUGH ELLIOT THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, LTD. AUTHOR OF "MODERN SCIENC\-<: AND THE ILLUSIONS OF PROFESSOR BRRGSON" TORONTO EDITOR OF H THE LETTERS OF JOHN STUART MILL," ETC., ETC. MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED ST. MARTIN'S STREET, LONDON TABLE OF CONTENTS P.4.GE INTRODUCTION xvii Life-The Philo8ophie Zoologique-Zoology-Evolution-In. heritance of acquired characters-Classification-Physiology Psychology-Conclusion. PREFACE· 1 Object of the work, and general observations on the subjects COPYRIGHT dealt with in it. PRELIMINARY DISCOURSE 9 Some general considerations on the interest of the study of animals and their organisation, especially among the most imperfect. PART I. CONSIDERATIONS ON THE NATURAL HISTORY OF ANIMALS, THEIR CHARACTERS, AFFINITIES, ORGANISATION, CLASSIFICATION AND SPECIES. CHAP. I. ON ARTIFICIAL DEVICES IN DEALING WITH THE PRO- DUCTIONS OF NATURE 19 How schematic classifications, classes, orders, families, genera and nomenclature are only artificial devices. Il. IMPORTANCE OF THE CONSIDERATION OF AFFINITIES 29 How a knowledge of the affinities between the known natural productions lies at the base of natural science, and is the funda- mental factor in a general classification of animals. -

Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve Management Plan 2011-2016

Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve Management Plan 2011-2016 April 1981 Revised, May 1982 2nd revision, April 1983 3rd revision, December 1999 4th revision, May 2011 Prepared for U.S. Department of Commerce Ohio Department of Natural Resources National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Division of Wildlife Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management 2045 Morse Road, Bldg. G Estuarine Reserves Division Columbus, Ohio 1305 East West Highway 43229-6693 Silver Spring, MD 20910 This management plan has been developed in accordance with NOAA regulations, including all provisions for public involvement. It is consistent with the congressional intent of Section 315 of the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended, and the provisions of the Ohio Coastal Management Program. OWC NERR Management Plan, 2011 - 2016 Acknowledgements This management plan was prepared by the staff and Advisory Council of the Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve (OWC NERR), in collaboration with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources-Division of Wildlife. Participants in the planning process included: Manager, Frank Lopez; Research Coordinator, Dr. David Klarer; Coastal Training Program Coordinator, Heather Elmer; Education Coordinator, Ann Keefe; Education Specialist Phoebe Van Zoest; and Office Assistant, Gloria Pasterak. Other Reserve staff including Dick Boyer and Marje Bernhardt contributed their expertise to numerous planning meetings. The Reserve is grateful for the input and recommendations provided by members of the Old Woman Creek NERR Advisory Council. The Reserve is appreciative of the review, guidance, and council of Division of Wildlife Executive Administrator Dave Scott and the mapping expertise of Keith Lott and the late Steve Barry. -

Cytogenetic Analysis, Heterochromatin

insects Article Cytogenetic Analysis, Heterochromatin Characterization and Location of the rDNA Genes of Hycleus scutellatus (Coleoptera, Meloidae); A Species with an Unexpected High Number of rDNA Clusters Laura Ruiz-Torres, Pablo Mora , Areli Ruiz-Mena, Jesús Vela , Francisco J. Mancebo , Eugenia E. Montiel, Teresa Palomeque and Pedro Lorite * Department of Experimental Biology, Genetics Area, University of Jaén, 23071 Jaén, Spain; [email protected] (L.R.-T.); [email protected] (P.M.); [email protected] (A.R.-M.); [email protected] (J.V.); [email protected] (F.J.M.); [email protected] (E.E.M.); [email protected] (T.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: The family Meloidae contains approximately 3000 species, commonly known as blister beetles for their ability to secrete a substance called cantharidin, which causes irritation and blistering in contact with animal or human skin. In recent years there have been numerous studies focused on the anticancer action of cantharidin and its derivatives. Despite the recent interest in blister beetles, cytogenetic and molecular studies in this group are scarce and most of them use only classical chromosome staining techniques. The main aim of our study was to provide new information in Citation: Ruiz-Torres, L.; Mora, P.; Meloidae. In this study, cytogenetic and molecular analyses were applied for the first time in the Ruiz-Mena, A.; Vela, J.; Mancebo, F.J.; family Meloidae. We applied fluorescence staining with DAPI and the position of ribosomal DNA in Montiel, E.E.; Palomeque, T.; Lorite, P. Hycleus scutellatus was mapped by FISH. Hycleus is one of the most species-rich genera of Meloidae Cytogenetic Analysis, but no cytogenetic data have yet been published for this particular genus. -

Concluding Remarks

Concluding Remarks The bulk of secretory material necessary for the encapsulation of spermatozoa into a spermatophore is commonly derived from the male accessory organs of re production. Not surprisingly, the extraordinary diversity in size, shape, and struc ture of the spermatophores in different phyla is frequently a reflection of the equally spectacular variations in the anatomy and secretory performance of male reproductive tracts. Less obvious are the reasons why even within a given class or order of animals, only some species employ spermatophores, while others de pend on liquid semen as the vehicle for spermatozoa. The most plausible expla nation is that the development of methods for sperm transfer must have been in fluenced by the environment in which the animals breed, and that adaptation to habitat, rather than phylogeny, has played a decisive role. Reproduction in the giant octopus of the North Pacific, on which our attention has been focussed, pro vides an interesting example. During copulation in seawater, which may last 2 h, the sperm mass has to be pushed over the distance of 1 m separating the male and female genital orifices. The metre-long tubular spermatophore inside which the spermatozoa are conveyed offers an obvious advantage over liquid semen, which could hardly be hauled over such a long distance. Apart from acting as a convenient transport vehicle, the spermatophore serves other purposes. Its gustatory and aphrodisiac attributes, the provision of an ef fective barrier to reinsemination, and stimulation of oogenesis and oviposition are all of great importance. Absolutely essential is its function as storage organ for spermatozoa, at least as effective as that of the epididymis for mammalian spermatozoa. -

Volume 42, Number 2 June 2015

Wisconsin Entomological Society N e w s I e t t e r Volume 42, Number 2 June 2015 Monitoring and Management - A That is, until volunteer moth surveyor, Steve Sensible Pairing Bransky, came onto the scene. Steve had By Beth Goeppinger, Wisconsin Department done a few moth and butterfly surveys here ofN atural Resources and there on the property. But that changed in 2013. Armed with mercury vapor lights, Richard Bong State Recreation Area is a bait and a Wisconsin scientific collector's heavily used 4,515 acre property in the permit, along with our permission, he began Wisconsin State Park system. It is located in surveying in earnest. western Kenosha County. The area is oak woodland, savanna, wetland, sedge meadow, He chose five sites in woodland, prairie and old field and restored and remnant prairie. savanna habitats. He came out many nights Surveys of many kinds and for many species in the months moths might be flying. After are done on the property-frog and toad, finding that moth populations seemed to drift fence, phenology, plants, ephemeral cycle every 3-5 days, he came out more ponds, upland sandpiper, black tern, frequently. His enthusiasm, dedication and grassland and marsh birds, butterfly, small never-ending energy have wielded some mammal, waterfowl, muskrat and wood surprising results. Those results, in turn, ducks to name a few. Moths, except for the have guided us in our habitat management showy and easy-to-identify species, have practices. been ignored. Of the 4,500 moth species found in the state, Steve has confirmed close to 1,200 on the property, and he isn't done yet! He found one of the biggest populations of the endangered Papaipema silphii moths (Silphium borer) in the state as well as 36 species of Catocola moths (underwings), them. -

Graellsia, 61(2): 225-255 (2005)

Graellsia, 61(2): 225-255 (2005) BIBLIOGRAFÍA Y REGISTROS IBERO-BALEARES DE MELOIDAE (COLEOPTERA) PUBLICADOS HASTA LA APARICIÓN DEL “CATÁLOGO SISTEMÁTICO GEOGRÁFICO DE LOS COLEÓPTEROS OBSERVADOS EN LA PENÍNSULA IBÉRICA, PIRINEOS PROPIAMENTE DICHOS Y BALEARES” DE J. M. DE LA FUENTE (1933) M. García-París1 y José L. Ruiz2 RESUMEN En las publicaciones actuales sobre faunística y taxonomía de Meloidae de la Península Ibérica se citan registros de autores del siglo XIX y principios del XX, uti- lizando como referencia principal las obras de Górriz Muñoz (1882) y De la Fuente (1933). Sin embargo, no se alude a las localidades precisas originales aportadas por otros autores anteriores o coetáneos. Consideramos que el olvido de todas esas citas supone una pérdida importante, tanto por su valor faunístico intrínseco, como por su utilidad para documentar la potencial desaparición de poblaciones concretas objeto de citas históricas, así como para detectar posibles modificaciones en el área de ocupa- ción ibérica de determinadas especies. En este trabajo reseñamos los registros ibéricos de especies de la familia Meloidae que hemos conseguido recopilar hasta la publica- ción del “Catálogo sistemático geográfico de los Coleópteros observados en la Península Ibérica, Pirineos propiamente dichos y Baleares” de J. M. de la Fuente (1933), y discutimos las diferentes posibilidades de adscripción específica cuando la nomenclatura utilizada no corresponde a la actual. Se eliminan del catálogo de espe- cies ibero-baleares: Cerocoma muehlfeldi Gyllenhal, 1817, -

Djvu Document

Vol. 5, No. 2, June 1991 65 On the Nomenclature and ClasSification of the Meloic;1ae (Coleoptera) Richard B. Selander Florida State Collection of Arthropods P. O. Box 147100 Gainesville, Florida 32614-7100 Abstract menelature (International Commission on Zoologi Forty-three availablefamily-group names (and three cal Nomenclature 1985). unavaillihle names) in Meloidae are listed as a basis fOr establishing nomenclatural priority. Available genus- , with indication of the type species of each; this is fol- Borcbmann (1917), and Kaszab (1969) have pub- lished classifications ofthe Meloidae to the generic or subgeneric level on a worldwide basis. None Of nomenc a ure. na y, a Classl Ica on 0 te amI y Meloidae to the subgeneric level is presented in which the three paid much attention to the priority of names at the famIly-group and genus-group levels are family-group names, nor in general ha"e the many treated in a manner consistent with the provisions ofthe authors who have dealt with restricted segments of InternatIOnal Code of ZoolOgIcal Nomenclature. TIils the meloid fauna. Kaszab's (1969) method of classification recognizes three subfamilies (Eleticinae, assigning authorship was particularly confusing In Meloinae, and Horiinae), 10 tribes, 15 subtribes, 116 violation of the ICZN and general practice in genera, and 66 subgenera. The subtribes Pyrotina and zoology, he gave authorship to the first author to Lydina (properly Alosimina), ofthe tribe Cerocomini, are use a name at a particular taxonomic level. For combined with the subtribe Lyttina. The tribe Steno- example, Eupomphini was CI edited to Selandel derini, of the subfamily Horiinae, is defined to include (l955b) but Eupomphina to Kaszab (1959) (actually Stenodera Eschscholtz.Epispasta Selanderistransferred from Cerocomini to Meloini. -

Berberomeloe, Real Olive Oil

Mini Review ISSN: 2574 -1241 DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2020.28.004644 Berberomeloe, Real Olive Oil García Segura Florence* Faculty of Medicine, Veterinary, Zoo, Benemérita Autonomous, University of Puebla, Mexico *Corresponding author: García Segura Florence, Faculty of Medicine, Veterinary, Zoo, Benemérita Autonomous, University of Puebla, Mexico ARTICLE INFO AbsTRACT Received: June 04, 2020 They have no defensive system, their black and red colors warn their predators of their bad taste. When defending, they secrete a blood-red hem lymphatic substance, Published: June 19, 2020 called cantharidin, which is very irritating to the touch. Adult size varies widely, from 15 to 75 mm [1]. Singharidin is excreted along with its blood (hemolymph) through lateral holes when it feels attacked or in danger. This reddish liquid if touched causes Citation: García Segura Florence. Berber- a burning sensation like that produced by boiling oil on the skin, hence its vulgar or omeloe, Real Olive Oil. Biomed J Sci & Tech common name. This substance is known as cantharidin which causes redness, rashes Res 28(3)-2020. BJSTR. MS.ID.004644. and irritation on contact with the skin. If you have oral contact, it causes nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and irritation in the urinary system and causes the erection of the penis, which is why it was previously considered an aphrodisiac substance. The signs that appear are: Five minutes after the poison deposit, edema begins, erythema; whitish their size; Later it appears, dizziness, hypertension, tachycardia, vomiting. spotDescription at the site orof characteristicsthe poison deposit. After fifteen minutes, the ampules accentuate Animalia Kingdom Insecta class Edge: Arthropoda Order: Coleoptera Family: Meloidae Subfamily: Meloinae Tribe: Lyttini Genre: Berberomeloe Species: B. -

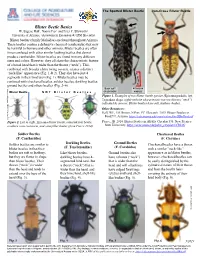

Blister Beetle Basics W

The Spotted Blister Beetle Iron-Cross Blister Beetle Blister Beetle Basics W. Eugene Hall1, Naomi Pier1 and Peter C. Ellsworth2 University of Arizona, 1Assistants in Extension & 2IPM Specialist Blister beetles (family Meloidae) are found throughout Arizona. These beetles contain a defensive chemical (cantharidin) that may be harmful to humans and other animals. Blister beetles are often times confused with other similar looking beetles that do not produce cantharidin. Blister beetles are found in many different sizes and colors. However, they all share the characteristic feature of a broad head that is wider than the thorax (“neck”). This, combined with broader elytra (wing covers), creates a distinct “neck-like” appearance (Fig. 1 & 2). They also have just 4 1 segments in their hind tarsi (Fig. 1). Blister beetles may be 2 confused with checkered beetles, soldier beetles, darkling beetles, 3 4 Figureground 8G. Adult beetles blister beetle, and Zonitis others atripennis beetles. (Fig.Figure 8H 2. –Adult6). blister beetle, Zonitis sayi. (Whitney (WhitneySandya Cranshaw, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org) Cranshaw, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org) BODY SOFT 4 TARSI IN Blister Beetle NOT Blister Beetles OR LEATHERY HINDLEG Athigiman Figure 1. Examples of two blister beetle species (Epicauta pardalis, left; Tegrodera aloga, right) with the characteristic narrow thorax (“neck”) , NMSU, Circular 536 Circular , NMSU, indicated by arrows. Blister beetles have soft, leathery bodies. Other Resources: Hall, WE, LM Brown, N Pier, PC Ellsworth. 2019. Blister Beetles in Food? U. Arizona. https://cals.arizona.edu/crops/cotton/files/BBinFood.pdf Figure 2. Left to right, Epicauta blister beetle, tamarisk leaf beetle, Pierce, JB.