GBV Awareness Toolkit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

God's Good Creation VBS

GOD’S o s d od worl G the CREATIONGOOD For loved Vacation Bible School Dear Leaders and Friends, Welcome to “God’s Good Creation,” ELCA World Hunger’s vacation Bible school! Helping children learn about hunger, hope and the work to which God calls us in the world is key to ending hunger for good. This program celebrates the gifts that God has created – gifts that can help build a world where all are fed. Working together with all of creation, we can look forward to the future God has promised. The themes for each of the five days of vacation Bible school in this program are drawn from projects supported by gifts to ELCA World Hunger. As you run the program in your congregation, we encourage you to support this work by collecting gifts for ELCA World Hunger. The craft suggestion for the first day – a goat bank – can be a great way to do this! The days are divided into four main sections: a large group opening, “family” time with small groups, rotations of activities and a large group closing. Please feel free to adapt this anyway that you like! In the first pages, you will find a daily overview and a sample schedule, with customizable schedules that you can copy and hand out to group leaders for quick reference. When a large, hungry crowd gathered to hear Jesus, he fed all of them with loaves of bread and fish. Many of us remember how the story ends – with a miraculous banquet – but where it began is important, too: with a small child and the gifts of God’s creation. -

By Dr. Shiva Ghaed

R O U T E 9 1 H e a l i n g f r o m M a s s V i o l e n c e & T r a u m a b y D r . S h i v a G h a e d Copyright 2018 by Shiva Geneviève Ghaed All Rights Reserved 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments Prologue 1 150 Minutes of Terror 2 Getting in the Trenches with my Patients 3 Road to Recovery: My Story 4 Road to Recovery: The Community 5 Laying the Groundwork: Dr. G’s Bucket Rules 6 Trauma 411 7 How PTSD Develops 8 Sleep Basics 9 Why Avoidance Makes It Worse 10 Finding New Meaning After Trauma 11 Anxiety and Panic 12 How to Change Unhelpful Thinking 13 Healthy Communication 14 Tips on Managing Nightmares 15 Leading Change by Example 16 Understanding Emotions and De-Coding Anger 17 Why Compassion Matters 18 Intrusive Memories and Catastrophic Thoughts 19 Role of Depression in Trauma 20 Grief and Loss 21 Cumulative Trauma 22 The Lessons We Have Learned 23 Final Thoughts 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my parents for teaching me the value of public service and community involvement, my sister for staying with me in cyberspace through a terrifying night, and all my friends and family for their unconditional support. The following people also merit mention for their support of the Route 91 community. The world is a better place because of you: Gary Martin and Mike Stack, managers of InCahoots in San Diego, CA – without your generosity we would not have had a place to come together and heal. -

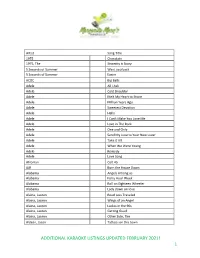

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

The Voices Project Script

The Voices Project Script written by Intro to Psychology students adapted by Alicia Nordstrom, Rebecca Steinberger, Patrick Hamilton, and Allan Austin © 2010 Alicia Nordstrom 1 Roles Narrator Alicia Nordstrom Previously overweight female (Kelly) Richelle Wesley Previously overweight female (Rena) Ashlee Danko African American female (adult) Sr Jean Messaros Gay male (adult) Chas Beleski Lesbian (adult) Melissa Sgroi Hispanic female (adult) Natalie DeWitt Woman in poverty Grace Riker Male with AIDS (Andy) Bruce Riley Woman with AIDS (Karla) Kit Foley Muslim Woman Rebecca Steinberger Muslim College Student Caitlin Hails Indian American Woman Erica Acosta Indian American Teenager Katie O'Hearn Student #1 (interviewed Josh) Tiffany Carotenuto Student #2 (interviewed Josh) Gerard Angeli Student #3 (interviewed Indian American Woman) Caitlin Hails Student #4 (interviewed Indian American Woman) Lauren Szabo Conclusion Alicia Nordstrom First performed on November 5, 2009 in Lemmond Theatre, Misericordia University, Dallas PA. 2 Scenes Introduction Alicia Community Indian American Woman, Indian American Teenager, Muslim Woman, Muslim College Student, Woman with AIDS, Lesbian Woman, Hispanic Woman) Kelly and Rena Previously Overweight Women The Media African-American Woman, Lesbian Woman, Hispanic Woman, Gay Man, Formerly Overweight Woman (Rena), Gay Man Emma Homeless Woman Marriage Muslim College Student, Indian American Teenager, Lesbian Woman, Muslim Woman, Indian American Woman, Gay Man Fear Factor Previously Overweight Woman (Kelly), Indian American Teenager, African American Woman, Gay Man, Muslim Woman, Woman with AIDS, Hispanic Woman, Lesbian Woman, Muslim College Student, Man with AIDS, Homeless Woman Andy and Karla Woman with AIDS, Man with AIDS The Other Emma Grace Contradictions Students #1, 2, 3, and 4 3 Introduction Alicia My name is Alicia Nordstrom and I am a psychology instructor here at Misericordia University. -

June Banner Format

St. Raphael the Archangel Episcopal Church Vol 55 Issue 6 June 2020 From the Rector Happy Pentecost season! By the time you all read this, we will have celebrated this new season of the church. I hope you are able to keep alongside all that your church is involved with during this strange time. The Spirit and the church is alive - in different ways, but still reaching out, drawing in, sharing good news, active in God’s mission. No one would say it is what we have been used to before, but we have also seen a certain creative adaptiveness that has been enabled by a sure loving of others as ourselves. I am so grateful to those who have continued as stewards of their gifts, time, talents during this time, those who have stepped Rev. Canon Dr. Helen up, those who are waiting patiently, and those who have joined me in prayer. Van Koevering None of us has experienced such a time as this. I have been on several steep learning curves at once, have appreciated those signs of life outside more than ever, and still haven’t got used to the crazy day-long rhythm of work, zooms, recordings, talking and listening. But I know for sure that all will be well. I am in the midst of a process that involves circles of various people (from the governor, TEC, NGO’s through to the diocese, other churches, clergy and our own vestry), all concerned with the how, what, when, where and why’s of re-entering church for services. -

ED332223.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 332 223 CS 212 855 TITLE Alaska Writing Assessment Pilot Survey 1988-89. INSTITUTION Alaska State Dept. of Education, Juneau. PUb DATE 89 NOTE 106p. PUB TYPE Reports - Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Correlation; Grade 10; High Schools; Holistic Evaluation; Public Schools; *Student Evaluation; Writing Ability; *Writing Evaluation; Writing Research IDENTIFIERS *Alaska; Analytical Scoring; Primary Trait Scoring ABSTRACT A study investigated what can be learned about the strengths and weaknesses of students' writing from direct assessment of writing performance and knowledge of overall student performance. In the first part of the study, all 13 school districts in Alaska participated in an interdistrict writing assessment procedure intended to measure the overall strengths and weaknesses of tenth graders' writing skills. Nine school districts participated in the second part of the study which correlated 668 tenth graders' performance in the direct writing assessment to their performance on standardized tests and to their grade point average. The subjects responded to a writing prompt concerning friendship and were given two 50-minute periods to write and revise their responses. The strengths and weaknesses of the subjects' writing abilities were analyzed for each of six writing traits: ideas and content; organization; voice; word cho:i.ce; sentence structure; and conventions. Results indicated that: (1) the relationships among the six writing traits were higher than the relationship with the standardized test result; (2) the strongest associations between writing traits and test scores occur with "sentence structure" and "conventions"; and (3) the weakest association between writing traits and test scoras occurs with "ideas and content" and "voice." Findings suggest that while the traits are strongly interrelated, they are in fact measuring different components of writing. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 United States

1 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT 2 ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 PUBLIC COMMENT ON CERTIFICATIION OF WASTE ISOLATION 13 PILOT PROJECT 14 15 SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO THURSDAY JANUARY 8, 1998 16 EVENING SESSION 7:00 P.M. TO 10:45 P.M. 17 18 19 EPA PANEL: RICHARD WILSON LARRY WEINSTOCK 20 FRANK MACINOWSKI MARY KRUGER 21 KEITH MATTHEWS 22 23 24 25 DAY 4 - JANUARY 6, 1998 - EVENING SESSION SANTA FE DEPOSITION SERVICE (505) 983-4643 1 I N D E X 2 TESTIMONY PAGE 3 DEIRDE BOAK 3 4 JEREMY BOAK 6 5 AUDREY CURRY 12 6 MICHAEL COLLINS 16 7 TIM CURRY 22 8 JOHN McCALL 29 9 POLLY RODDICK 33 10 WENDELL WEARTH 35 11 PRISCILLA LOGAN 39 12 JOHN DENDAHL 41 13 STANLEY TENORIO 44 14 DOLORES BACA 46 15 AMY MANNING 49 16 MIKE DEPMSEY 52 17 SASHA PYLE 56 18 LES SHEPHARD 67 19 GREG MELLO 71 20 ALFRED FULLER 78 21 HARPER F. BREWER 79 22 JOSE VILLEGAS 83 23 AMY SOLLMAN 88 24 ELIZABETH WEST 93 25 STANLEY LOGAN 97 DAY 4 - JANUARY 6, 1998 - EVENING SESSION SANTA FE DEPOSITION SERVICE (505) 983-4643 3 1 PARRISH STAPLES 100 2 JEAN NICHOLS 102 3 JAY SHELTON 108 4 TRACY HUGHES 115 5 JAI LAKSHMAN 117 6 JEAN WHEELER 128 7 KEITH MACKINTOSH 130 8 DON SMITH 132 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 DAY 4 - JANUARY 6, 1998 - EVENING SESSION SANTA FE DEPOSITION SERVICE (505) 983-4643 1 1 PROCEEDINGS 2 SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO, THURSDAY, JANUARY 8, 1998 3 EVENING SESSION 4 MR. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

Anxiety Management Package

ANXIETY MANAGEMENT PACKAGE ANXIETY •Overview •Generalized Anxiety Disorder •Your anxiety •Panic and panic attacks INTERVENTIONS •Coping skills •Unhelpful thinking styles •Untwisting your thinking •Challenging anxious thoughts •Accepting uncertainty WORRYING •How worry works •Rumination and worry •Postpone your worry •Worry thought record •Worrying well SOCIAL ANXIETY •Overview and strategies •Social anxiety thought record Page 1 of 4 ANXIETY Anxiety is the body's way of responding to being in danger. Adrenaline is rushed into our bloodstream to enable us to run away or fight. This happens whether the danger is real, or whether we believe the danger is there when actually there is none. It is the body's alarm and survival mechanism. Primitive man wouldn't have survived for long without this life-saving response. It works so well, that it often kicks in when it's not needed - when the danger is in our heads rather than in reality. We think we're in danger, so that's enough to trigger the system to go, go, go! People who get anxious tend to get into scanning mode - where they're constantly on the lookout for danger, hyper-alert to any of the signals, and make it more likely that the alarm system will be activated. Thoughts that often occur relate to our overestimating or exaggerating the actual threat and underestimating or minimising our ability to cope: I'm in danger right now The worst possible scenario is going to happen I won't be able to cope with it www.get.gg © Carol Vivyan 2009-2015, permission to use for therapy purposes www.getselfhelp.co.uk/anxiety.htm Page 2 of 4 Behaviours might include: Avoiding people or places Not going out Going to certain places at certain times, e.g. -

Volume CXXXX, Number 8, May 28, 2021

The Student Newspaper of Lawrence University Since 1884 THE VOL. CXXXX NO. LAWRENTIAN8 APPLETON, WISCONSIN MAY 28, 2021 $15 Minimum Wage Movement THIS WEEK IN PHOTOS: sets agenda for coming months Family Cookout The Black Student Union (BSU) and Committee Caleb Yuan the administration in the next benefits. Staff Writer academic year, the initiative will During the conversation be- on Diversity Affairs (CODA) collaborated to host _________________________________ present their concerns to LUCC in tween the two groups, the Union an end-of-the-year cookout on May 22. The event The “Pay Us 15” initiative, the hope of gaining potential sup- of Grinnell Student Dining Work- founded by junior Barrah Sham- port, according to Freeman. Their ers offered some suggestions, such featured food, music and games held on the Quad. oon, continues its effort towards list of concerns addresses issues as focusing on a specific worker raising student workers’ mini- including the impact of a low pay demographic before expanding mum wage in Spring Term, under rate on the mental well-being of the campaign, doing mass move- the leaderships of Students for a those who come from underprivi- ment such as distributing fliers Democratic Society (SDS), Sun- leged backgrounds, decreased and holding demonstrations, as rise Appleton and Student Libera- financial aid packages for interna- well as waiting for administrative tion Front (SLF). tional students and the disparities changes in National Labor Rela- As of now, the initiative has between student’s received wage tion Board (NLRB) during this set several agendas including ap- and the cost of tuition, books, summer. -

TRANSCRIPT CRTO.OQ - Criteo SA at Goldman Sachs Technology and Internet Conference (Virtual)

REFINITIV STREETEVENTS EDITED TRANSCRIPT CRTO.OQ - Criteo SA at Goldman Sachs Technology and Internet Conference (Virtual) EVENT DATE/TIME: FEBRUARY 11, 2021 / 3:30PM GMT REFINITIV STREETEVENTS | www.refinitiv.com | Contact Us ©2021 Refinitiv. All rights reserved. Republication or redistribution of Refinitiv content, including by framing or similar means, is prohibited without the prior written consent of Refinitiv. 'Refinitiv' and the Refinitiv logo are registered trademarks of Refinitiv and its affiliated companies. FEBRUARY 11, 2021 / 3:30PM, CRTO.OQ - Criteo SA at Goldman Sachs Technology and Internet Conference (Virtual) CORPORATE PARTICIPANTS Megan Clarken Criteo S.A. - CEO & Director CONFERENCE CALL PARTICIPANTS Heath Patrick Terry Goldman Sachs Group, Inc., Research Division - MD PRESENTATION Heath Patrick Terry - Goldman Sachs Group, Inc., Research Division - MD Great. My name is Heath Terry. Thank you all so much for joining us. Really excited to have with us today, CEO of Criteo. Megan, thank you so much for taking the time to join us. Megan Clarken - Criteo S.A. - CEO & Director It's a pleasure. Thanks for inviting me. QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS Heath Patrick Terry - Goldman Sachs Group, Inc., Research Division - MD So just to get started, obviously, I think a lot of people viewing right now know Criteo, the company. But for those that are maybe less, less familiar, what is it that you and the team there are trying to build? Megan Clarken - Criteo S.A. - CEO & Director Well, let's start with we're a tech company, and we're focused on e-commerce. Our clients are commerce players, they're retailers, they're brand owners, they're media owners.