An Inverse Latitudinal Diversity Gradient in European Bryophytes Received: 26 November 2015 Rubén G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prescribed Fire Decreases Lichen and Bryophyte Biomass and Alters Functional Group Composition in Pacific Northwest Prairies Author(S): Lalita M

Prescribed Fire Decreases Lichen and Bryophyte Biomass and Alters Functional Group Composition in Pacific Northwest Prairies Author(s): Lalita M. Calabria, Kate Petersen, Sarah T. Hamman and Robert J. Smith Source: Northwest Science, 90(4):470-483. Published By: Northwest Scientific Association DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3955/046.090.0407 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.3955/046.090.0407 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Lalita M. Calabria1, Kate Petersen,The Evergreen State College, 2700 Evergreen Parkway NW, Olympia, Washington 98505 Sarah T. Hamman, The Center for Natural Lands Management, 120 Union Ave SE #215, Olympia, Washington 98501 and Robert J. Smith, Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, 2082 Cordley Hall, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97331 Prescribed Fire Decreases Lichen and Bryophyte Biomass and Alters Functional Group Composition in Pacific Northwest Prairies Abstract The reintroduction of fire to Pacific Northwest prairies has been useful for removing non-native shrubs and supporting habitat for fire-adapted plant and animal species. -

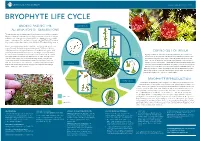

Bryophyte Life Cycle

MARCH 2016LEARNING | VELD & FLORA ABOUT BIODIVERSITY Veld & Flora MARCHFACTSHEET: 2016 | VELD MOSS & FLORA 24 25 3. BRYOPHYTE LIFE CYCLE Gametophyte (n) UNDERSTANDING THE GERMINATION MALE ALTERNATION OF GENERATIONS The way that almost all land plants reproduce is by means of two distinct, alternating life forms, a sexual phase that produces and releases gametes or sex cells and allows fertilisation, and a dispersal phase – both of which are adaptations to an essentially waterless environment. The sexual phase is known as the GAMETOPHYTE or haploid spores (n) generation and the dispersal phase is the SPOROPHYTE or diploid (2n) generation. Mature gametophyte plants produce haploid sex cells (egg and sperm) in sex organs (the male antheridia and female archegonia). These sex cells (also called gametes) fuse during fertilisation to form a diploid (2n) zygote which COPING OUT OF WATER grows, by means of mitosis (that results in two daughter cells each having Sperm (n) the same number and kind of chromosomes as the parent cell), into a new released Bryophytes, which include moss, are primitive plants that give us some idea sporophyte plant. The diploid sporophyte produces haploid (n) spores (i.e. from male of how the first plants that ventured onto land coped with their new waterless FEMALE each spore has a single set of chromosomes) by means of the process environment. They share many features with other plants, but differ in some of cell division called meiosis. Meiosis results in four daughter cells each ways – such as the lack of an effective vascular system (specialised tissue for with half the number of chromosomes of the parent cell. -

The Origin of Alternation of Generations in Land Plants

Theoriginof alternation of generations inlandplants: afocuson matrotrophy andhexose transport Linda K.E.Graham and LeeW .Wilcox Department of Botany,University of Wisconsin, 430Lincoln Drive, Madison,WI 53706, USA (lkgraham@facsta¡.wisc .edu ) Alifehistory involving alternation of two developmentally associated, multicellular generations (sporophyteand gametophyte) is anautapomorphy of embryophytes (bryophytes + vascularplants) . Microfossil dataindicate that Mid ^Late Ordovicianland plants possessed such alifecycle, and that the originof alternationof generationspreceded this date.Molecular phylogenetic data unambiguously relate charophyceangreen algae to the ancestryof monophyletic embryophytes, and identify bryophytes as early-divergentland plants. Comparison of reproduction in charophyceans and bryophytes suggests that the followingstages occurredduring evolutionary origin of embryophytic alternation of generations: (i) originof oogamy;(ii) retention ofeggsand zygotes on the parentalthallus; (iii) originof matrotrophy (regulatedtransfer ofnutritional and morphogenetic solutes fromparental cells tothe nextgeneration); (iv)origin of a multicellularsporophyte generation ;and(v) origin of non-£ agellate, walled spores. Oogamy,egg/zygoteretention andmatrotrophy characterize at least some moderncharophyceans, and arepostulated to represent pre-adaptativefeatures inherited byembryophytes from ancestral charophyceans.Matrotrophy is hypothesizedto have preceded originof the multicellularsporophytes of plants,and to represent acritical innovation.Molecular -

Extant Diversity of Bryophytes Emerged from Successive Post-Mesozoic Diversification Bursts

ARTICLE Received 20 Mar 2014 | Accepted 3 Sep 2014 | Published 27 Oct 2014 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms6134 Extant diversity of bryophytes emerged from successive post-Mesozoic diversification bursts B. Laenen1,2, B. Shaw3, H. Schneider4, B. Goffinet5, E. Paradis6,A.De´samore´1,2, J. Heinrichs7, J.C. Villarreal7, S.R. Gradstein8, S.F. McDaniel9, D.G. Long10, L.L. Forrest10, M.L. Hollingsworth10, B. Crandall-Stotler11, E.C. Davis9, J. Engel12, M. Von Konrat12, E.D. Cooper13, J. Patin˜o1, C.J. Cox14, A. Vanderpoorten1,* & A.J. Shaw3,* Unraveling the macroevolutionary history of bryophytes, which arose soon after the origin of land plants but exhibit substantially lower species richness than the more recently derived angiosperms, has been challenged by the scarce fossil record. Here we demonstrate that overall estimates of net species diversification are approximately half those reported in ferns and B30% those described for angiosperms. Nevertheless, statistical rate analyses on time- calibrated large-scale phylogenies reveal that mosses and liverworts underwent bursts of diversification since the mid-Mesozoic. The diversification rates further increase in specific lineages towards the Cenozoic to reach, in the most recently derived lineages, values that are comparable to those reported in angiosperms. This suggests that low diversification rates do not fully account for current patterns of bryophyte species richness, and we hypothesize that, as in gymnosperms, the low extant bryophyte species richness also results from massive extinctions. 1 Department of Conservation Biology and Evolution, Institute of Botany, University of Lie`ge, Lie`ge 4000, Belgium. 2 Institut fu¨r Systematische Botanik, University of Zu¨rich, Zu¨rich 8008, Switzerland. -

Bryophyte Diversity and Vascular Plants

DISSERTATIONES BIOLOGICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 75 BRYOPHYTE DIVERSITY AND VASCULAR PLANTS NELE INGERPUU TARTU 2002 DISSERTATIONES BIOLOGICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 75 DISSERTATIONES BIOLOGICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 75 BRYOPHYTE DIVERSITY AND VASCULAR PLANTS NELE INGERPUU TARTU UNIVERSITY PRESS Chair of Plant Ecology, Department of Botany and Ecology, University of Tartu, Estonia The dissertation is accepted for the commencement of the degree of Doctor philosophiae in plant ecology at the University of Tartu on June 3, 2002 by the Council of the Faculty of Biology and Geography of the University of Tartu Opponent: Ph.D. H. J. During, Department of Plant Ecology, the University of Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands Commencement: Room No 218, Lai 40, Tartu on August 26, 2002 © Nele Ingerpuu, 2002 Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastuse trükikoda Tiigi 78, Tartu 50410 Tellimus nr. 495 CONTENTS LIST OF PAPERS 6 INTRODUCTION 7 MATERIAL AND METHODS 9 Study areas and field data 9 Analyses 10 RESULTS 13 Correlation between bryophyte and vascular plant species richness and cover in different plant communities (I, II, V) 13 Environmental factors influencing the moss and field layer (II, III) 15 Effect of vascular plant cover on the growth of bryophytes in a pot experiment (IV) 17 The distribution of grassland bryophytes and vascular plants into different rarity forms (V) 19 Results connected with nature conservation (I, II, V) 20 DISCUSSION 21 CONCLUSIONS 24 SUMMARY IN ESTONIAN. Sammaltaimede mitmekesisus ja seosed soontaimedega. Kokkuvõte 25 < TÄNUSÕNAD. Acknowledgements 28 REFERENCES 29 PAPERS 33 2 5 LIST OF PAPERS The present thesis is based on the following papers which are referred to in the text by the Roman numerals. -

Havens for Wildlife

)"7&/4'038*-%-*'& 4FDUJPO# .PTTFT -JWFSXPSUTBOE'FSOT This sheet explains what mosses, liverworts and Liverworts ferns are, where they occur and guidelines on how Liverworts are similar to to care for them in a burial ground. mosses but tend to be The earliest land plants were related to ferns and leafy and are less common. mosses. They started life growing on the edge of lakes Liverworts are mostly found and rivers 400 million years ago. Today most ferns, in woodland and by streams mosses and liverworts still need to grow in moist or rivers but can also be found places. on shady stones and damp soil in burial grounds. They are With our damp climate many burial sites prove ideal for strange, distinctive looking ferns, mosses and liverworts, particularly in the western plants and worth looking at areas of Britain and Ireland. closely or photographing their Adder’s-tongue Fern intricate shapes and subtle colours. MOSSES AND LIVERWORTS Mosses and liverworts are known as FERNS ‘bryophytes’. They are small, green plants *OUIFDPPM XFUDMJNBUFPGUIF6,UIFSFBSFUZQFTPG which do not have !owers or seeds but fern. Look out for ferns on west or north facing walls produce spores instead. There are over in particular. The shady areas of burial grounds, and 1000 di"erent species of bryophyte in under trees, where grass cutters don’t reach, will also UIF6,BOEUIFZUFOEUPCFGPVOEJO be places where ferns can !ourish undisturbed. sheltered, damp places as most of them cannot survive drying out. Few mosses An amazing fact about ferns is that once established PSMJWFSXPSUTIBWF&OHMJTIOBNFTBOEB they can survive in quite dry places, such as walls. -

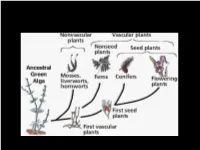

Plant Evolution and Diversity Part 1: Bryophytes and Ferns the Three Domains • Plant-Like Protists Are Autotrophs – They Contain Chloroplasts and Make Their Own Food

Plant Evolution and Diversity Part 1: Bryophytes and Ferns The Three Domains • Plant-like protists are autotrophs – they contain chloroplasts and make their own food. • Animal-like and fungus-like protists and are heterotrophs. Fungi – not plants Non-photosynthetic eukaryotes, saprophytic, Reproduce by spores, chitin cell walls (not cellulose) Includes yeast What is a plant? Traditional View of Biology: Animals and Plants Problem: Microscopic Organisms (Bacteria, Fungi, Algae) Complication: Endosymbiotic origin of organelles (Lynn Margulis) Membrane-bound structures in eukaryotic cells are derived from formerly free-living organisms that have become intimately symbiotic What is a Plant? 1. Eukaryotic - nucleus 2. Chloroplasts present 3. Cell wall with cellulose 4. Autotrophic – make own food What is a Plant? 1. Eukaryotic 2. Chloroplasts present 3. Cell wall with cellulose 4. Autotrophic 5. Complex Life Cycle (alternation of generations) Algae - Diverse, single-celled to complex seaweeds Photosynthetic eukaryotes, green plants Plant-like protists – “Algae” • Diverse group – green, red, and brown algae. • Single celled or multicellular. • Autotrophs (plants), form the foundation of Earth’s food chains. • Produce much of Earth’s oxygen. Green Algae – Chlorophytes and Charophytes • Chlorophyll a and b, like land plants • Many forms – single celled, filamentous, colonial, sheets • May have other pigments, orange or red • Related to land plants Ulva – Sea Lettuce • Chlorophyte - Marine • Sheets 2 cells thick • Alternation of Generations like land plants Chara – Stonewort • Charophyte • Freshwater • Calcium carbonate deposits, crusty feel branch • Whorls of branches • Reproductive structures at nodes main axis node a. Chara, several individuals b. One individual a: © Bob Gibbons/Alamy; b: © Kingsley Stern The phylogeny of land plants The likely ancestor are charophycean algae • same chloroplast DNA, ribosomal DNA • same membrane structure, peroxisomes, sperm cells Chara Land plants are most closely related to freshwater green algae known as charophytes. -

Moss:Liverworts:Lichen:Fern Reference Websites

Moss, liverwort and fern websites: EfloraBC moss species. Encyclopedic list, but many photos and species descriptions are missing: http://linnet.geog.ubc.ca/DB_Query/QueryForm.aspx?__VIEWSTATE= %2FwEPDwULLTE2MjU4NzcyMjNkGAEFHl9fQ29udHJvbHNSZXF1aXJlUG9zdEJhY2t LZXlfXxYEBQhjaGtFeGFjdAUIY2hrVGh1bWIFEWNoa05vbkVzdGFibGlzaGVkBQhjaGt BdGxhc8Sd5ZLsV21c03zbdfYd3dDZBNrzpsKvfRe7Pq7BiDcY&__VIEWSTATEGENER ATOR=F43EC70C&__EVENTVALIDATION= %2FwEdACcYOb1tMPNo24DCMTb6eBqDY3pPM72C6ENlxoAMiL5klY48fSFybqZHBiO J7lzAyWdm9VQeeMVQckpxgMtgvm5Cwk%2FdwNI%2Fd6ZpJDaouyJMaWplwzk %2BuCWbsoDaxgUcPIzm%2FwsKpieTdBJU9u0E14aYs3J4hL %2FFOih0hliT318nsTIxlubO%2FSWXRZDkiF5L0e5fq3YH471H %2BVawBjFGJmZZWFxv0aEGctT8b%2Frwhgfy6LjJaRpKx1y4ZT4u1Hr7sxdj6FbRb %2FZgSfv31qBjuRD14Zh7D1AK9KYE %2BIi3uBM6cliB9owX8WB41mOq6BXxQpso0kjvSXrDUDp96QEGVBVELLHIrxP65KJP 3SpSeuG3HQevSks5zKknNfbofDqoPVlUaZXPCPeefWYCjL%2BaFNjnXT95a %2F2FCNv32dDxLTODC0Coq9x4oX47eid2hUhPeFv9BUqNxEqQJtirBRBN7hrbfPJ4NE jdf4Ph5KkU4L%2BNRM6qd9Uz4hWZp36PzRrGCuPW77ffb7hAbc7t7CRfMQ1L %2F6ga8qIvl2pELg%2FfmHBYTWaCJseqkNQOHjOJ0aO %2BoWhCuCpzjgGrC8n1NGBY1IelntNHbw47TKMVys %2FSbCFSo0TdcaCR2SdiwG37J9K3bQQ6R50exhEL1kvt7xUR24yzq6mZryXyspKOb Au0dURNDGjyTbgTupb38OrMUe0%2FPoaXbo2JqVECzCNrdPUE1sEngiOeiqqU8F7E L61V%2FaDwFH3dfgZ4e5uJQmTFAxjonlxZOEaKfs4RTs %2FTtwQrPvyu9pg3lwaYX9LJak %2FZYVkdPZS2ct5G7yzGldOyzv3gwyry8I6IVjtFcaRfcDaWl1OJ1eCdCpWd5H2Jxozyt %2FX6cg%3D %3D&Family=&InvStatus=Both&rdRedBlue=Both&rdlPlanGroup=9&Genus=&Species= &SubSpecies=&Variety=&EnglishName=&chkThumb=on&SubmitForm=Search Fernzenmosses good photos of 100 selected mosses -

Embryophyta - Jean Broutin

PHYLOGENETIC TREE OF LIFE – Embryophyta - Jean Broutin EMBRYOPHYTA Jean Broutin UMR 7207, CNRS/MNHN/UPMC, Sorbonne Universités, UPMC, Paris Keywords: Embryophyta, phylogeny, classification, morphology, green plants, land plants, lineages, diversification, life history, Bryophyta, Tracheophyta, Spermatophyta, gymnosperms, angiosperms. Contents 1. Introduction to land plants 2. Embryophytes. Characteristics and diversity 2.1. Human Use of Embryophytes 2.2. Importance of the Embryophytes in the History of Life 2.3. Phylogenetic Emergence of the Embryophytes: The “Streptophytes” Concept 2.4. Evolutionary Origin of the Embryophytes: The Phyletic Lineages within the Embryophytes 2.5. Invasion of Land and Air by the Embryophytes: A Complex Evolutionary Success 2.6. Hypotheses about the First Appearance of Embryophytes, the Fossil Data 3. Bryophytes 3.1. Division Marchantiophyta (liverworts) 3.2. Division Anthocerotophyta (hornworts) 3.3. Division Bryophyta (mosses) 4. Tracheophytes (vascular plants) 4.1. The “Polysporangiophyte Concept” and the Tracheophytes 4.2. Tracheophyta (“true” Vascular Plants) 4.3. Eutracheophyta 4.3.1. Seedless Vascular Plants 4.3.1.1. Rhyniophyta (Extinct Group) 4.3.1.2. Lycophyta 4.3.1.3. Euphyllophyta 4.3.1.4. Monilophyta 4.3.1.5. Eusporangiate Ferns 4.3.1.6. Psilotales 4.3.1.7. Ophioglossales 4.3.1.8. Marattiales 4.3.1.9. Equisetales 4.3.1.10. Leptosporangiate Ferns 4.3.1.11. Polypodiales 4.3.1.12. Cyatheales 4.3.1.13. Salviniales 4.3.1.14. Osmundales 4.3.1.15. Schizaeales, Gleicheniales, Hymenophyllales. 5. Progymnosperm concept: the “emblematic” fossil plant Archaeopteris. 6. Seed plants 6.1. Spermatophyta 6.1.1. Gymnosperms ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) PHYLOGENETIC TREE OF LIFE – Embryophyta - Jean Broutin 6.1.2. -

Bryo-Activities: a Review on How Bryophytes Are Contributing to the Arsenal of Natural Bioactive Compounds Against Fungi

plants Review Bryo-Activities: A Review on How Bryophytes Are Contributing to the Arsenal of Natural Bioactive Compounds against Fungi Mauro Commisso 1,† , Francesco Guarino 2,† , Laura Marchi 3,†, Antonella Muto 4,†, Amalia Piro 5,† and Francesca Degola 6,*,† 1 Department of Biotechnology, University of Verona, Cà Vignal 1, Strada Le Grazie 15, 37134 Verona (VR), Italy; [email protected] 2 Department of Chemistry and Biology, University of Salerno, Via Giovanni Paolo II 132, 84084 Fisciano (SA), Italy; [email protected] 3 Department of Medicine and Surgery, Respiratory Disease and Lung Function Unit, University of Parma, Via Gramsci 14, 43125 Parma (PR), Italy; [email protected] 4 Department of Biology, Ecology and Earth Sciences, University of Calabria, Via Ponte P. Bucci 6b, Arcavacata di Rende, 87036 Cosenza (CS), Italy; [email protected] 5 Laboratory of Plant Biology and Plant Proteomics (Lab.Bio.Pro.Ve), Department of Chemistry and Chemical Technologies, University of Calabria, Ponte P. Bucci 12 C, Arcavacata di Rende, 87036 Cosenza (CS), Italy; [email protected] 6 Department of Chemistry, Life Sciences and Environmental Sustainability, University of Parma, Parco delle Scienze 11/A, 43124 Parma (PR), Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] † All authors equally contributed to the manuscript. Abstract: Usually regarded as less evolved than their more recently diverged vascular sisters, which currently dominate vegetation landscape, bryophytes seem having nothing to envy to the defensive arsenal of other plants, since they had acquired a suite of chemical traits that allowed them to Citation: Commisso, M.; Guarino, F.; adapt and persist on land. In fact, these closest modern relatives of the ancestors to the earliest Marchi, L.; Muto, A.; Piro, A.; Degola, F. -

Special Issue: Bryophytes California Native Plant Society Fremontia Membership Vol

$8.00 (Free to Members) Vol. 31, No. 3 July 2003 FREMONTIA A JOURNAL OF THE CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY IN THIS ISSUE: A CONVERSATION ABOUT MOSSES, LIVERWORTS, AND HORNWORTS by Dan Norris 5 MOSS GEOGRAPHY AND FLORISTICS IN CALIFORNIA by James R. Shevock 12 THE ROLE OF THE AMATEUR IN BRYOLOGY: TALES OF AN AMATEUR BRYOLOGIST by Kenneth Kellman 21 MOSSES IN THE DESERT? by Lloyd R. Stark 26 THE BIOLOGY OF BRYOPHYTES, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO WATER by Brent D. Mishler 34 VOLUME 31:3, JULY 2003 FREMONTIA 1 SPECIAL ISSUE: BRYOPHYTES CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY FREMONTIA www.cnps.org MEMBERSHIP VOL. 31, NO. 3, JULY 2003 Dues include subscriptions to Fremontia and the Bulletin. Copyright © 2003 Mariposa Lily . $1,000 Supporting . $75 California Native Plant Society Benefactor . $500 Family, Group, International . $45 Patron . $250 Individual or Library . $35 Linda Ann Vorobik, Editor Plant Lover . $100 Student/Retired/Limited Income . $20 Daniel Norris & James R. Shevock, Convening Editors CONTACTS CHAPTER COUNCIL Bob Hass, Copy Editor CNPS, 2707 K Street, Suite 1 Alta Peak (Tulare) . Joan Stewart Beth Hansen-Winter, Designer Sacramento, CA 95816-5113 Bristlecone (Inyo-Mono) . (916) 447-CNPS (2677) Stephen Ingram CALIFORNIA NATIVE Fax: (916) 447-2727 Channel Islands . Lynne Kada PLANT SOCIETY [email protected] Dorothy King Young (Mendocino/ Sonoma Coast) . Lori Hubbart Dedicated to the Preservation of Sacramento Office Staff: East Bay . Tony Morosco the California Native Flora Executive Director . Pamela C. El Dorado . Amy Hoffman Muick, PhD Kern County . Laura Stockton The California Native Plant Society Los Angeles/Santa Monica Mtns . Development Director . -

Bryophyte Systematics - Claudio Delgadillo M

BIOLOGICAL SCIENCE FUNDAMENTALS AND SYSTEMATICS – Vol. III – Bryophyte Systematics - Claudio Delgadillo M. BRYOPHYTE SYSTEMATICS Claudio Delgadillo M. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico Keywords: mosses, Musci, liverworts, anthocerotes, hornworts, hepaticae, terpenoids, m-chromosomes, embryophytes, Antocerotophyta, Marchantiophyta. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Morphology 2.1 Anthocerotae (Hornworts) 2.2 Hepaticae (Liverworts) 2.3 Musci (Mosses) 3. Distinguishing Features Among Groups 4. Sources of Systematic Data 4.1 Ontogeny 4.2 Cytology 4.3 Chemistry 4.4 Paleobotany 5. Phylogenetic Relationships 6. Classification 7. Future Research Acknowledgments Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary The bryophytes are land plants characterized by a heteromorphic life cycle in which the haploid green phase, the gametophyte, is the dominant thalloid or foliose plant. The diploid generation, the unbranched sporophyte, remains attached to the gametophyte and is photosynthetic for a short time. Molecular data indicate that the three groups traditionally included in the bryophytes do not constitute a natural monophyletic group, and the UNESCOclassification of the higher categories – EOLSS has thus been modified to reflect their relationship as they are understood at present. SAMPLE CHAPTERS According to the current classification, the Division Marchantiophyta (hepaticae or liverworts) represents the basal lineage of all land plants, while the Division Antocerotophyta (hornworts) and the Division Bryophyta (musci or mosses) are more closely related to each other than to the liverworts. The mosses are the sister group to other land plants, the tracheophytes. The hypotheses behind this classification have not received universal support and additional morphologic information, molecular data, and cladistic analyses are required to determine the phylogenetic relationships of these plants. ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) BIOLOGICAL SCIENCE FUNDAMENTALS AND SYSTEMATICS – Vol.