Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oldiemarkt-Journal 4-2006

S c h a l l p l a t t e n b Ö r s e n O l d i e M a r k t 0 4 / 0 6 3 SchallplattenbÖrsen sind seit einigen Jahren fester Bestandteil der euro- pÄischen Musikszene. Steigende Be- sucherzahlen zeigen, da¿ sie lÄngst nicht mehr nur Tummelplatz fÜr Insider sind. Neben teuren RaritÄten bieten die HÄndler gÜnstige Second-Hand-Platten, Fachzeitschriften, BÜcher Lexika, Pos- ter und ZubehÖr an. Rund 250 BÖrsen finden pro Jahr allein in der Bundes- republik statt. Oldie-Markt verÖffent- licht als einzige deutsche Zeit-schrift monatlich den aktuellen BÖrsen-kalen- der. Folgende Termine wurden von den Veranstaltern bekanntgegeben: D a t u m S t a d t / L a n d V e r a n s t a l t u n g s - O r t V e r a n s t a l t e r / T e l e f o n 1. April Hamburg Uni Mensa WIR ¤ (05 11) 763 93 84 1. April Mannheim Rosengarten Wolfgang W. Korte ¤ (061 01) 12 86 62 2. April NÜrnberg Meistersingerhalle First&Last ¤ (03 41) 699 56 80 2. April Oberhausen Revierpark Vonderort Agentur Lauber ¤ (02 11) 955 92 50 2. April Braunschweig Mensa 2 Beethovenstra¿e WIR ¤ (05 11) 763 93 84 2. April Trier Europahalle Wolfgang W. Korte ¤ (061 01) 12 86 62 7. April Utrecht/Holland Jaarbeurs ARC ¤ (00 31) 229 21 38 91 8. April Freiburg Haus der Jugend Frank Geisler ¤ (07 61) 383 73 89 8. April Eisenach BÜrgerhaus Iris Lange ¤ (056 59) 73 24 9. -

Cultural Images of Contemporary

Masaryk University Faculty of Education DepartmentofEnglishLanguageandLiterature A COURSE DESIGN : CULTURAL IMAGES OF CONTEMPORARY BRITAIN IN POPULAR LYRICS Diploma Thesis Brno2007 ŠárkaMlčochová Supervisor: Mgr.Lucie Podroužková,PhD. Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci zpracovala samostatně a použila jen pramenyuvedenévseznamuliteratury. ____________________ ŠárkaMlčochová I would like to thank Mgr. Lucie Podroužková, PhD. for her kind and patient supervision and for the advice she provided to me during my work on this diploma thesis. CONTENT 4 _______________________________________________________________________ 1. INTRODUCTION 6 1.1. ARGUMENT 6 1.2. POPULAR CULTURE 7 1.3. LEARNING A SECOND CULTURE 10 1.3.1. WHY POPULAR LYRICS ? 12 1.4. HOW TO USE THE TEXTBOOK 12 1.5. PREFACE TO THE TEXTBOOK 14 2. THE TEXTBOOK 16 2.1. MONARCHY , POLITICS AND CLASS 16 2.1.1. GOD SAVE THE QUEEN 16 2.1.2. MR. CHURCHILL SAYS 18 2.1.3. POST WORLD WAR II BLUES 20 2.1.4. SHIPBUILDING , ISLAND OF NO RETURN 21 2.1.5. GHOST TOWN 24 2.1.6. A DESIGN FOR LIFE 24 2.1.7. COCAINE SOCIALISM , TONY BLAIR 25 2.1.8. I’M WITH STUPID 27 2.1.9. GORDON BROWN 28 2.2. LIFESTYLE , LEISURE AND MEDIA 30 2.2.1. TOO YOUNG TO BE MARRIED 30 2.2.2. YOUNG TURKS 31 2.2.3. NO CLAUSE 28 32 2.2.4. KASHKA FROM BAGHDAD 33 2.2.5. PROBLEM CHILD 34 2.2.6. HERE COMES THE WEEKEND , POOR PEOPLE 35 2.2.7. TWO PINTS OF LAGER AND A PACKET OF CRISPS PLEASE , 37 HURRY UP HARRY 2.2.8. -

Karaoke Song Book Karaoke Nights Frankfurt’S #1 Karaoke

KARAOKE SONG BOOK KARAOKE NIGHTS FRANKFURT’S #1 KARAOKE SONGS BY TITLE THERE’S NO PARTY LIKE AN WAXY’S PARTY! Want to sing? Simply find a song and give it to our DJ or host! If the song isn’t in the book, just ask we may have it! We do get busy, so we may only be able to take 1 song! Sing, dance and be merry, but please take care of your belongings! Are you celebrating something? Let us know! Enjoying the party? Fancy trying out hosting or KJ (karaoke jockey)? Then speak to a member of our karaoke team. Most importantly grab a drink, be yourself and have fun! Contact [email protected] for any other information... YYOUOU AARERE THETHE GINGIN TOTO MY MY TONICTONIC A I L C S E P - S F - I S S H B I & R C - H S I P D S A - L B IRISH PUB A U - S R G E R S o'reilly's Englische Titel / English Songs 10CC 30H!3 & Ke$ha A Perfect Circle Donna Blah Blah Blah A Stranger Dreadlock Holiday My First Kiss Pet I'm Mandy 311 The Noose I'm Not In Love Beyond The Gray Sky A Tribe Called Quest Rubber Bullets 3Oh!3 & Katy Perry Can I Kick It Things We Do For Love Starstrukk A1 Wall Street Shuffle 3OH!3 & Ke$ha Caught In Middle 1910 Fruitgum Factory My First Kiss Caught In The Middle Simon Says 3T Everytime 1975 Anything Like A Rose Girls 4 Non Blondes Make It Good Robbers What's Up No More Sex.... -

Die Ramones Als Helden Der Pop-Kultur

Nutzungshinweis: Es ist erlaubt, dieses Dokument zu drucken und aus diesem Dokument zu zitieren. Wenn Sie aus diesem Dokument zitieren, machen Sie bitte vollständige Angaben zur Quelle (Name des Autors, Titel des Beitrags und Internet-Adresse). Jede weitere Verwendung dieses Dokuments bedarf der vorherigen schriftlichen Genehmigung des Autors. Quelle: http://www.mythos-magazin.de CHRISTIAN BÖHM Die Ramones als Helden der Pop-Kultur Inhalt 1. Einleitung 2. Punk und Pop 2.1 Punk und Punk Rock: Begriffsklärung und Geschichte 2.1.1 Musik und Themen 2.1.2 Kleidung 2.1.3 Selbstverständnis und Motivation 2.1.4 Regionale Besonderheiten 2.1.5 Punk heute 2.2 Exkurs: Pop-Musik und Pop-Kultur 2.3 Rekurs: Punk als Pop 3. Mythen, Helden und das Star-System 3.1 Der traditionelle Mythos- und Helden-Begriff 3.2 Der moderne Helden- bzw. Star-Begriff innerhalb des Star-Systems 4. Die Ramones 4.1 Einführung in das ‚ Wesen ’ Ramones 4.1.1 Kurze Biographie der Ramones 4.1.2 Musikalische Charakteristika 4.2 Analysen und Interpretationen 4.2.1 Analyse von Presseartikeln und Literatur 4.2.1.1 Zur Ästhetik der Ramones 4.2.1.1.1 Die Ramones als ‚ Familie ’ 4.2.1.1.2 Das Band-Logo 4.2.1.1.3 Minimalismus 4.2.1.2 Amerikanischer vs. britischer Punk: Vergleich von Ramones und Sex Pistols 4.2.1.3 Die Ramones als Helden 4.2.1.4 Eine typisch amerikanische Band? 4.2.2 Analyse von Ramones-Songtexten 4.2.2.1 Blitzkrieg Bop 4.2.2.2 Sheena Is A Punk Rocker 4.2.2.3 Häufig vorkommende Motive und Thematiken in Texten der Ramones 4.2.2.3.1 Individualismus 4.2.2.3.2 Motive aus dem Psychiatrie- Comic- und Horror-Kontext 4.2.2.3.3 Das Deutsche als Klischee 4.2.2.3.4 Spaß / Humor 4.3 Der Film Rock’n’Roll High School 4.3.1 Kurze Inhaltsangabe des Films 4.3.2 Analyse und Interpretation des Films 4.3.2.1 Die Protagonistin: Riff Randell [...] Is A Punk Rocker 4.3.2.2 Die Antagonistin: Ms. -

Record-Mirror-1978-0

July 29, 1978 15p 1 - PISTOLS STEVE, PAUL AND SID CLOUT IN COLOUR IG o 1! 14 1{ OWING to technical difficulties last week's British album chart has been reprinted. p Ip, SINGLES UKALBUMS USsINciS' ALBUMS 1 YOU'RE THRONE THAT WANT. Trevolta Newton -john RSO RSO 1 SHADOW DANCING, Andy Gibb RSO 1 GREASE, Soundtrack 1 1 SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER. Various RSO 211 2 2 S%,RIF SONG, Father Abraham Dices 2 2 BAKER STREET, Gerry Ralferry Unhed Artists 2 1 SOME GIRLS. Rolling Stenos Rolling Stones 2 2 LIVE AND DANGEROUS, Thin Uuy Vertigo 3 4 SUBSTITUTE, Clout Carrara 3 3 klISS YOU. Rolling Stones Rolling Stones 3 5 NATURAL HIGH, Commodores Morown 3 4 SOME GIRLS, Rolling Stones EMI 4 3 DANCING IN THE CITY, Marshall Hain Harvest 1 P 4 5 LAST DANCE, Donna Summer Casablanca 4 4 STRANGER IN TOWN, Bob Seger Canna 4 5 THE KICK INSIDE, Kate Bush EMI S to BOOGIE 0001E BOGIE. A Taste Of Honey Caonoi 5 6 GREASE Frankle Valli RSO 5 8 DARKNESS AT THE EDGE Bruce Sodnoetoen Co imbia 5 - 20 GOLDEN GREATS, The Hollins EMI 6 6 LIKE CLOCKWORK, Boomtown Rats Ensign 6 10 THREE TIMES A LADY, Commodores Motown 6 3 CITY TO CITY Gerry Rafferty Unhed Aman 6 3 STREET LEGAL. Bob Dylan CBS 7 5 A LITTLE BIT OF SOAP. Showaddvweddy Arista 7 4 STILL THE SAME, Bob Seger Caphol 7 7 SHADOW DANCING, Andy Gibb RSO 7 7 OCTAVE, Moody Blues Dicta 8 7 WILD WEST HERO, Electric Light Orchestra Jet B 8 USE TA BE MY GIRL O'Jays Phil let 8 9 DOUBLE VISION, Foreigner Atlantic 8 10 WAR OF THE WORLDS, Jeff Wayne s Musical Version CBS 9 8 AIRPORT, Motors Virgin 9 7 THE GROOVE LINE, Heetwave Epic 9 B SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER. -

Audio Mastering for Stereo & Surround

AUDIO MASTERING FOR STEREO & SURROUND 740 BROADWAY SUITE 605 NEW YORK NY 10003 www.thelodge.com t212.353.3895 f212.353.2575 EMILY LAZAR, CHIEF MASTERING ENGINEER EMILY LAZAR CHIEF MASTERING ENGINEER Emily Lazar, Grammy-nominated Chief Mastering Engineer at The Lodge, recognizes the integral role mastering plays in the creative musical process. Combining a decisive old-school style and sensibility with an intuitive and youthful knowledge of music and technology, Emily and her team capture the magic that can only be created in the right studio by the right people. Founded by Emily in 1997, The Lodge is located in the heart of New York City’s Greenwich Village. Equipped with state-of-the art mastering, DVD authoring, surround sound, and specialized recording studios, The Lodge utilizes cutting-edge technologies and attracts both the industry’s most renowned artists and prominent newcomers. From its unique collection of outboard equipment to its sophisticated high-density digital audio workstations, The Lodge is furnished with specially handpicked pieces that lure both analog aficionados and digital audio- philes alike. Moreover, The Lodge is one of the few studios in the New York Metropolitan area with an in-house Ampex ATR-102 one-inch two-track tape machine for master playback, transfer and archival purposes. As Chief Mastering Engineer, Emily’s passion for integrating music with technology has been the driving force behind her success, enabling her to create some of the most distinctive sounding albums released in recent years. Her particular attention to detail and demand for artistic integrity is evident through her extensive body of work that spans genres and musical styles, and has made her a trailblazer in an industry notably lack- ing female representation. -

Elogio Del Punk, La Colonna Sonora Del Disagio Di Fine Millennio

18VAR01A1806 ZALLCALL 12 19:47:59 06/17/97 Mercoledì 18 giugno 1997 12 l’Unità2 LINEE eSUONI Riflessioni attorno a «Teste Vuote Ossa Rotte 97» il megaconcerto di Bologna con gli Sham 69 e Agnostic Front Legge per A Sanremo Due festival la musica Elogio del punk, la colonna sonora s’incontrano I dubbi di Incontro fra la musica italia- na e quella latino-americana, incontro fra due festival ca- Claudia Mori del disagio di fine millennio nori: quello di Sanremo e quello di Vina del Mar. Il pri- Si stringono i tempi per la Perchè questo suono «antico» sembra ancora in grado di interpretare gli umori, le ansie, la rabbia di oggi. Il punk goliardico mo meeting fra le due città «Legge per la musica», dei Toydolls e il rock n’ roll ad alto potenziale dei New Bomb Turks. C’erano anche i Voodoo Glow Skull e i Klasse Kriminale musicali avverràsabatoaSan- che Veltroni presenterà il remo in una manifestazione 21 giugno, e cominciano intitolata: «Sanremo - Vina già a diffondersi speranze, dubbi e BOLOGNA. La prima volta che ho hippie che si ostinavano ad ascoltare terminato, coi capelli lunghi fino del Mar, Ballando, bailando» malumori. Qualcosa da avuto sottomano un disco degli i vecchi dinosauri del rock, vent’anni alle spalle ricorda un po‘ Iggy Pop che sarà trasmessa in diretta dire ce l’ha Claudia Mori, «Sham 69» devo aver avuto quindici fa. Eppure il punk, a giudicare dalla e la sua band è dura ed efficiente, da Rai 1 alle 20.50 e poche ore la signora Celentano, qui anni.Erail1978eildiscoera«TellUs grande affluenza di pubblico, è anco- molto meglio di quella del «Live» E gli epigoni hanno dopo in differita sul canale di nella veste di The Truth», il primo Lp di Pursey e ra vivo - sicuramente non è mai stato in Giappone di qualche anno fa. -

“Lo Llaman Democracia Y No Lo Es”: a Cultural Interpretation of the Politics of Punk in Spain

“LO LLAMAN DEMOCRACIA Y NO LO ES”: A CULTURAL INTERPRETATION OF THE POLITICS OF PUNK IN SPAIN By David Vila Diéguez Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Spanish May 10, 2019 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Andrés Zamora, Ph.D. Edward H. Friedman, Ph.D. N. Michelle Murray, Ph.D. Luis Martín-Cabrera, Ph.D. Iros todos a la mierda, de uno en uno o en mogollón. Todos a la puta mierda, valientemente y con decisión. Iros todos a la mierda, estamos hartos de corrupción. Todos a la puta mierda, estamos hartos, ¡me cago en dios! “Iros todos a la mierda” La Polla Acabar con lo establecido, poner fin a la disciplina, borrar más de mil normas sin sentido, caminar sin dueños ni policía. Rechazar cualquier forma de estado ejércitos, jerarquías y mandos, romper las barreras que han puesto en tu vida, y quitarnos el peso de su justicia. “Que deje de ser una utopía” Disidencia ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work would not have been possible if my grandfather Antonio (a.k.a. “o Limiao”) had been killed while serving in the Spanish Civil War. It would have probably also not been possible had the Guardia Civil caught him smuggling nuts, coffee, and different essential goods through the Galicia-Portugal border in Tamaguelos (Ourense) in the years following the Civil War. If it wasn’t for my grandmother, Clotilde, who raised nine children and moved to the Basque Country with Antonio to work there for years, this work would have never happened. -

AND YOU WILL KNOW US Mistakes & Regrets .1-2-5 What

... AND YOU WILL KNOW US Mistakes & Regrets .1-2-5 What You Don't Know 10 COMMANDMENTS Not True 1989 100 FLOWERS The Long Arm Of The Social Sciences 100 FLOWERS The Long Arm Of The Social Sciences 100 WATT SMILE Miss You 15 MINUTES Last Chance For You 16 HORSEPOWER 16 Horsepower A&M 540 436 2 CD D 1995 16 HORSEPOWER Sackcloth'n'Ashes PREMAX' TAPESLEEVES PTS 0198 MC A 1996 16 HORSEPOWER Low Estate PREMAX' TAPESLEEVES PTS 0198 MC A 1997 16 HORSEPOWER Clogger 16 HORSEPOWER Cinder Alley 4 PROMILLE Alte Schule 45 GRAVE Insurance From God 45 GRAVE School's Out 4-SKINS One Law For Them 64 SPIDERS Bulemic Saturday 198? 64 SPIDERS There Ain't 198? 99 TALES Baby Out Of Jail A GLOBAL THREAT Cut Ups A GUY CALLED GERALD Humanity A GUY CALLED GERALD Humanity (Funkstörung Remix) A SUBTLE PLAGUE First Street Blues 1997 A SUBTLE PLAGUE Might As Well Get Juiced A SUBTLE PLAGUE Hey Cop A-10 Massive At The Blind School AC 001 12" I 1987 A-10 Bad Karma 1988 AARDVARKS You're My Loving Way AARON NEVILLE Tell It Like It Is ABBA Ring Ring/Rock'n Roll Band POLYDOR 2041 422 7" D 1973 ABBA Waterloo (Swedish version)/Watch Out POLYDOR 2040 117 7" A 1974 ABDELLI Adarghal (The Blind In Spirit) A-BONES Music Minus Five NORTON ED-233 12" US 1993 A-BONES You Can't Beat It ABRISS WEST Kapitalismus tötet ABSOLUTE GREY No Man's Land 1986 ABSOLUTE GREY Broken Promise STRANGE WAYS WAY 101 CD D 1995 ABSOLUTE ZEROS Don't Cry ABSTÜRZENDE BRIEFTAUBEN Das Kriegen Wir schon Hin AU-WEIA SYSTEM 001 12" D 1986 ABSTÜRZENDE BRIEFTAUBEN We Break Together BUCKEL 002 12" D 1987 ABSTÜRZENDE -

Queer Youth and the Importance of Punk Rock

QUEERING PUNK: QUEER YOUTH AND THE IMPORTANCE OF PUNK ROCK DENISE SCOTT A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO DECEMBER 2011 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-90087-1 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-90087-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

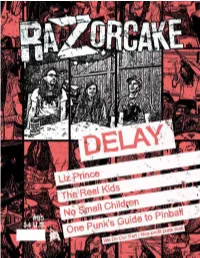

Razorcake Issue #85 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT Through out 2014 we surveyed new subscribers asking how they heard about Razorcake and why they decided to order a subscription. The answers were varied, reflecting the If you wish to donate through the mail, uniqueness of the DIY punk experience. But there a couple please rip this page out and send it to: answers that were repeated. Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. A somewhat common response to the first question was PO Box 42129 that they had been introduced to Razorcake through a friend. Los Angeles, CA 90042 So to all you friends out there: thank you! Keep up the good work. A word of mouth campaign is our dream. Your personal NAME: endorsement makes us proud. The leading response to the second question was that they ordered the subscription because they wanted to support the ADDRESS: magazine. Again: thank you! It is very much appreciated. Subscriptions and advertising is what keeps us afloat. We can’t physically fit anymore advertising into the magazine, but the world is full of people who have yet to subscribe. EMAIL: If you’re considering ordering a subscription but want to avoid the hassle, we’ve set up a self-renewing plan through Paypal. You sign up once and it automatically withdraws the DONATION money once a year. You never have to do anything ever again. AMOUNT: It can be found here– Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California non-profit corporation, is http://www.razorcake.org/announcements/sign-up-for-a- registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status self-renewing-razorcake-subscription (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United States IRS. -

TAZ-TFG-2017-3281.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS: 1. Introduction 2 2. Academia and popular music 6 3. Britain in the seventies 9 4. The emergence of punk in Britain 12 5. A brand new identity 16 6. Music for the revolution 17 7. Shock the audiences 20 8. Conclusion 22 9. References 23 10. Appendix The Clash: The Clash (1977) 26 Sex Pistols: Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols (1977) 31 1 1. INTRODUCTION For once in my life I've got something to say I wanna say it now for now is today A love has been given so why not enjoy So let's all grab and let's all enjoy! If the kids are united Then we'll never be divided ( Sham 69 , “If The Kids Are United”) It has been forty years since the Clash and the Sex pistols released their first albums and the status of punk has changed a lot. Nowadays it is more usual that people may wear colourful hair, piercings or tattoos than it was decades ago. It is also more common that pop songs feature the presence of songs with sexual themes or national and/or social criticism. Punk has been reduced to teenagers whose desire for breaking the rules and being different to their parents is bigger than their principles and their praises for punk idols. The Sex Pistols disappeared long time ago and the dream of the Clash also vanished decades ago. Punk has finally been commodified and accepted and, consequently, its power seems to have vanished in the crowd of teenagers with spiky colourful hair, leather jackets and safety pins.