Thesis Filing Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Can Hear Music

5 I CAN HEAR MUSIC 1969–1970 “Aquarius,” “Let the Sunshine In” » The 5th Dimension “Crimson and Clover” » Tommy James and the Shondells “Get Back,” “Come Together” » The Beatles “Honky Tonk Women” » Rolling Stones “Everyday People” » Sly and the Family Stone “Proud Mary,” “Born on the Bayou,” “Bad Moon Rising,” “Green River,” “Traveling Band” » Creedence Clearwater Revival “In-a-Gadda-Da-Vida” » Iron Butterfly “Mama Told Me Not to Come” » Three Dog Night “All Right Now” » Free “Evil Ways” » Santanaproof “Ride Captain Ride” » Blues Image Songs! The entire Gainesville music scene was built around songs: Top Forty songs on the radio, songs on albums, original songs performed on stage by bands and other musical ensembles. The late sixties was a golden age of rock and pop music and the rise of the rock band as a musical entity. As the counterculture marched for equal rights and against the war in Vietnam, a sonic revolution was occurring in the recording studio and on the concert stage. New sounds were being created through multitrack recording techniques, and record producers such as Phil Spector and George Martin became integral parts of the creative process. Musicians expanded their sonic palette by experimenting with the sounds of sitar, and through sound-modifying electronic ef- fects such as the wah-wah pedal, fuzz tone, and the Echoplex tape-de- lay unit, as well as a variety of new electronic keyboard instruments and synthesizers. The sound of every musical instrument contributed toward the overall sound of a performance or recording, and bands were begin- ning to expand beyond the core of drums, bass, and a couple guitars. -

“Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson

The Interplay of Authority, Masculinity, and Signification in the “Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Holly Johnson ii Abstract This thesis will deconstruct the "grunge killed '80s metal” narrative, to reveal the idealization by certain critics and musicians of that which is deemed to be authentic, honest, and natural subculture. The central theme is an analysis of the conflicting masculinities of glam metal and grunge music, and how these gender roles are developed and reproduced. I will also demonstrate how, although the idealized authentic subculture is positioned in opposition to the mainstream, it does not in actuality exist outside of the system of commercialism. The problematic nature of this idealization will be examined with regard to the layers of complexity involved in popular rock music genre evolution, involving the inevitable progression from a subculture to the mainstream that occurred with both glam metal and grunge. I will illustrate the ways in which the process of signification functions within rock music to construct masculinities and within subcultures to negotiate authenticity. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my academic advisor Dr. William Echard for his continued patience with me during the thesis writing process and for his invaluable guidance. I also would like to send a big thank you to Dr. James Deaville, the head of Music and Culture program, who has given me much assistance along the way. -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Thinking Plague a History Of

What the press has said about: THINKING PLAGUE A HISTORY OF MADNESS CUNEIFORM 2003 lineup: Mike Johnson (guitars & such), Deborah Perry (singing), Dave Willey (bass guitar & accordions), David Shamrock (drums & percussion), Mark Harris (saxes, clarinet, flute), Matt Mitchell (piano, harmonium, synths) - Guests: Kent McLagan (acoustic bass), Jean Harrison (fiddle), Ron Miles (trumpet), David Kerman (drums and percussion), Leslie Jordan (voice), Mark McCoin (samples and various exotica) “It has been 20 years since Rock In Opposition ceased to exist as a movement in any official sense… Nevertheless, at its best this music can be stimulating and vital. It’s only RIO, but I like it. Carrying the torch for these avant Progressive refuseniks are Thinking Plague, part of a stateside Cow-inspired contingent including 5uu’s and Motor Totemist Guild. These groups have…produced some extraordinary work… Their music eschews the salon woodwinds and cellos of the European groups for a more traditional electric palette, and its driving, whirlwind climaxes show a marked influence of King Crimson and Yes, names to make their RIO granddaddies run screaming from the room. …this new album finds the group’s main writer Mike Johnson in [an] apocalyptic mood, layering the pale vocals of Deborah Perry into a huge choir of doom, her exquisitely twisted harmonies spinning tales of war, despair and redemption as the music becomes audaciously, perhaps absurdly, complex. … Thinking Plague are exciting and ridiculous in equal measure, as good Prog rock should be.” - Keith Moliné, Wire, Issue 239, January 2004 “Thinking Plague formed in 1983…after guitarist and main composer Mike Johnson answered a notice posted by Bob Drake for a guitarist into “Henry Cow, Yes, etc.” …these initial influences are still prominent in the group’s sound - along with King Crimson, Stravinsky, Ligeti, Art Bears, and Univers Zero. -

Stop Smiling Magazine :: Interviews and Reviews: Film + Music

Stop Smiling Magazine :: Interviews and Reviews: Film + Music + Books ... http://www.stopsmilingonline.com/story_print.php?id=1097 Downtown Dedication: The Return of Polvo (Touch and Go) Monday, June 23, 2008 By Dan Pearson We could have flown out of Newark, landed in Charlotte, and just hit a barbecue spot in Reidsville, but this was after all the Polvo reunion and it deserved more. We needed to feel as if we were making the descent, notice the disparity in New England and Southern spring, endure interminable DC traffic and feel that we had earned our ribs and slaw. So, I packed the Malibu with I-Roy and U-Roy, stomached $4 gas and my friend Bose and I left from Connecticut in a rainstorm, both of us in fleece. Night one we spent at a Ramada in Fredericksburg, never made it to the battlefield or historic downtown, but instead drove down the divided highway to Allman’s BBQ. I’m wary of food blogs, but the culinary scribes were dead-on: best ribs I have ever had outside Texas, enviable pulled pork and slaw, notable sauce in the squirt bottle — all in an old corner diner with spinning stools. What a foundation, not only for the evening, which consisted of ice cold tap Yuengling and inebriated dancing to Def Leppard in the Ramada lounge, but for the show to come. Just a stateline south, yes, Polvo, the seminal math rock quartet, reunited at their Ground Zero, the Cat’s Cradle in Carrboro. In the morning, it was only better, the slow slalom down Route 40 country roads leaving trails of red clay and another barbecue platter at Short Sugar’s in Danville, Virginia. -

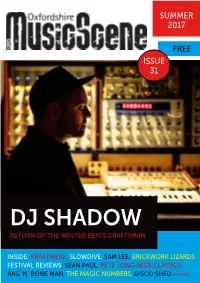

Dj Shadow Return of the Master Beats Craftsman

SUMMER 2017 FREE ISSUE 31 DJ SHADOW RETURN OF THE MASTER BEATS CRAFTSMAN INSIDE: KRAFTWERK, SLOWDIVE, SAM LEE, BRICKWORK LIZARDS FESTIVAL REVIEWS: SEAN PAUL, PETE TONG IBIZA CLASSICS, RAG ‘N’ BONE MAN, THE MAGIC NUMBERS, DISCO SHED & MORE OMS31 MUSIC NEWS There’s a history of multi – venue metro festivals in Cowley Road with Truck’s OX4 and then Gathering setting the pace. Well now Future Perfect have taken up the baton with Ritual Union on Saturday October 21. Venues are the O2 Academy 1 and 2, The Library, The Bullingdon and Truck Store. The first stage of acts announced includes Peace, Toy, Pinkshinyultrablast, Flamingods, Low Island, Dead Reborn local heroes Ride are sounding in fine stage Pretties, Her’s, August List and Candy Says with DJ fettle judging by their appearance at the 6 Music sets from the Drowned in Sound team. Tickets are Festival in Glasgow. The former Creation shoegaze £25 in advance. trailblazers play the New Theatre, Oxford on July 10, having already appeared at Glastonbury, their The Jericho Tavern in Walton Street have a new first local show in many years. They have also promoter to run their upstairs gigs. Heavy Pop announced a major UK tour. The eagerly awaited are well – known in Reading having run the Are new album, the Erol Alkan produced Weather Diaries You Listening? festival there for 5 years. Already is just released. (See our album review in the Local confirmed are an appearance from Tom Williams Releases section). Tickets for New Theatre gig with (formerly of The Boat) on September 16 and Original Spectres supporting, can be bought from Rabbit Foot Spasm Band on October 13 with atgtickets.com Peerless Pirates and Other Dramas. -

Reed First Pages

4. Northern England 1. Progress in Hell Northern England was both the center of the European industrial revolution and the birthplace of industrial music. From the early nineteenth century, coal and steel works fueled the economies of cities like Manchester and She!eld and shaped their culture and urban aesthetics. By 1970, the region’s continuous mandate of progress had paved roads and erected buildings that told 150 years of industrial history in their ugly, collisive urban planning—ever new growth amidst the expanding junkyard of old progress. In the BBC documentary Synth Britannia, the narrator declares that “Victorian slums had been torn down and replaced by ultramodern concrete highrises,” but the images on the screen show more brick ruins than clean futurescapes, ceaselessly "ashing dystopian sky- lines of colorless smoke.1 Chris Watson of the She!eld band Cabaret Voltaire recalls in the late 1960s “being taken on school trips round the steelworks . just seeing it as a vision of hell, you know, never ever wanting to do that.”2 #is outdated hell smoldered in spite of the city’s supposed growth and improve- ment; a$er all, She!eld had signi%cantly enlarged its administrative territory in 1967, and a year later the M1 motorway opened easy passage to London 170 miles south, and wasn’t that progress? Institutional modernization neither erased northern England’s nineteenth- century combination of working-class pride and disenfranchisement nor of- fered many genuinely new possibilities within culture and labor, the Open Uni- versity notwithstanding. In literature and the arts, it was a long-acknowledged truism that any municipal attempt at utopia would result in totalitarianism. -

Harmonic Resources in 1980S Hard Rock and Heavy Metal Music

HARMONIC RESOURCES IN 1980S HARD ROCK AND HEAVY METAL MUSIC A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Theory by Erin M. Vaughn December, 2015 Thesis written by Erin M. Vaughn B.M., The University of Akron, 2003 M.A., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by ____________________________________________ Richard O. Devore, Thesis Advisor ____________________________________________ Ralph Lorenz, Director, School of Music _____________________________________________ John R. Crawford-Spinelli, Dean, College of the Arts ii Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................... v CHAPTER I........................................................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 1 GOALS AND METHODS ................................................................................................................ 3 REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE............................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER II..................................................................................................................................... 36 ANALYSIS OF “MASTER OF PUPPETS” ...................................................................................... -

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 122 September Oxford’s Music Magazine 2005 SupergrassSupergrassSupergrass on a road less travelled plus 4-Page Truck Festival Review - inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] THE YOUNG KNIVES won You Now’, ‘Water and Wine’ and themselves a coveted slot at V ‘Gravity Flow’. In addition, the CD Festival last month after being comes with a bonus DVD which picked by Channel 4 and Virgin features a documentary following Mobile from over 1,000 new bands Mark over the past two years as he to open the festival on the Channel recorded the album, plus alternative 4 stage, alongside The Chemical versions of some tracks. Brothers, Doves, Kaiser Chiefs and The Magic Numbers. Their set was THE DOWNLOAD appears to have then broadcast by Channel 4. been given an indefinite extended Meanwhile, the band are currently in run by the BBC. The local music the studio with producer Andy Gill, show, which is broadcast on BBC recording their new single, ‘The Radio Oxford 95.2fm every Saturday THE MAGIC NUMBERS return to Oxford in November, leading an Decision’, due for release on from 6-7pm, has had a rolling impressive list of big name acts coming to town in the next few months. Transgressive in November. The monthly extension running through After their triumphant Truck Festival headline set last month, The Magic th Knives have also signed a publishing the summer, and with the positive Numbers (pictured) play at Brookes University on Tuesday 11 October. -

DISCO! an Interdisciplinary Conference

DISCO! An Interdisciplinary Conference 21-23 June 2018 Attenborough Centre for the Creative Arts University of Sussex WELCOME TO DISCO! This programme provides a full schedule for the conference. For further information about the presentations and the contributors, please refer to the abstracts section on the conference website: https://discosussex2018.wordpress.com If you would like to use wifi, the venue password is: upliftingly scoff their raven If you would like to tweet our conference, please do! @disco_conf We would love to hear from you about your experience at Disco! There is a comments book at the registration desk and a feedback section on the conference website. Recommendations of local eats and drinks in Brighton can also be found on the website. If you have an emergency and need to speak to a conference organiser, please call Arabella (07747 797 254), Michael (07973 317876) or Mimi (07492 771318) or email [email protected] The conference organisers would like to thank the Drama Public Programme, the School of English, the School of Media, Film and Music, everyone at the Attenborough Centre for the Creative Arts, and especially, Greg Mickelborough, Laura McDermott, Matt Knight, Nicola Jeffs, Melissa Cox, and Jodie Grey, and our colleagues Patrick Reed, Sarah Maddox, Danielle Salvage, Lizzie Thynne, Jason Price, Carol Watts, Wayne Spicer, and Alison O’Gorman. A special thanks to our student stewards: Zoë Bothwell, Tom Chown, Neve Mclennon, and Jemima Harney. Catering: spacewithus A big thank you to everyone who is sharing their work at Disco! Enjoy the conference! The DISCO! Team Mimi Haddon Michael Lawrence Arabella Stanger Thursday 21 June 1.30 – 2.00 Gardner Tower Registration and Refreshments 2.00 – 2.15 ACCA Auditorium Welcome! 2.15 – 3.30 ACCA Auditorium Keynote Presentation Melissa Blanco Borelli (Royal Holloway, University of London) "Put Your Body In It": Disco, Divas, and Dance Studies Stephanie Mills’ disco classic, “Put Your Body In It” invites us to get up, free ourselves and just dance. -

JAMES D. BABCOCK, MBA, CFA, CPA 191 South Salem Road Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 (203) 994-7244 [email protected]

JAMES D. BABCOCK, MBA, CFA, CPA 191 South Salem Road Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 (203) 994-7244 [email protected] List of Addendums First Addendum – Middle Ages Second Addendum – Modern and Modern Sub-Categories A. 20th Century B. 21st Century C. Modern and High Modern D. Postmodern and Contemporary E. Descrtiption of Categories (alphabetic) and Important Composers Third Addendum – Composers Fourth Addendum – Musical Terms and Concepts 1 First Addendum – Middle Ages A. The Early Medieval Music (500-1150). i. Early chant traditions Chant (or plainsong) is a monophonic sacred form which represents the earliest known music of the Christian Church. The simplest, syllabic chants, in which each syllable is set to one note, were probably intended to be sung by the choir or congregation, while the more florid, melismatic examples (which have many notes to each syllable) were probably performed by soloists. Plainchant melodies (which are sometimes referred to as a “drown,” are characterized by the following: A monophonic texture; For ease of singing, relatively conjunct melodic contour (meaning no large intervals between one note and the next) and a restricted range (no notes too high or too low); and Rhythms based strictly on the articulation of the word being sung (meaning no steady dancelike beats). Chant developed separately in several European centers, the most important being Rome, Hispania, Gaul, Milan and Ireland. Chant was developed to support the regional liturgies used when celebrating Mass. Each area developed its own chant and rules for celebration. In Spain and Portugal, Mozarabic chant was used, showing the influence of North Afgican music. The Mozarabic liturgy survived through Muslim rule, though this was an isolated strand and was later suppressed in an attempt to enforce conformity on the entire liturgy. -

Political Political Theory

HarvardSpring 8 Summer 2016 Contents Trade................................................................................. 1 Philosophy | Political Theory | Literature ...... 26 Science ........................................................................... 33 History | Religion ....................................................... 35 Social Science | Law ................................................... 47 Loeb Classical Library ..............................................54 Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library ...................... 56 I Tatti Renaissance Library .................................... 58 Distributed Books ...................................................... 60 Paperbacks .....................................................................69 Recently Published ................................................... 78 Index ................................................................................79 Order Information .................................................... 80 cover: Detail, “Erwin Piscator entering the Nollendorftheater, Berlin” by Sasha Stone, 1929. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art. Gift of Henrick A. Berinson and Adam J. Boxer; Ubu Gallery, New York. 2007.3.2 inside front cover: Shutterstock back cover: Howard Sokol / Getty Images The Language Animal The Full Shape of the Human Linguistic Capacity Charles Taylor “There is no other book that has presented a critique of conventional philosophy of language in these terms and constructed an alternative to it in anything like this way.” —Akeel