Video and the Origins of Electronic Photography Revised

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multimedia Systems DCAP303

Multimedia Systems DCAP303 MULTIMEDIA SYSTEMS Copyright © 2013 Rajneesh Agrawal All rights reserved Produced & Printed by EXCEL BOOKS PRIVATE LIMITED A-45, Naraina, Phase-I, New Delhi-110028 for Lovely Professional University Phagwara CONTENTS Unit 1: Multimedia 1 Unit 2: Text 15 Unit 3: Sound 38 Unit 4: Image 60 Unit 5: Video 102 Unit 6: Hardware 130 Unit 7: Multimedia Software Tools 165 Unit 8: Fundamental of Animations 178 Unit 9: Working with Animation 197 Unit 10: 3D Modelling and Animation Tools 213 Unit 11: Compression 233 Unit 12: Image Format 247 Unit 13: Multimedia Tools for WWW 266 Unit 14: Designing for World Wide Web 279 SYLLABUS Multimedia Systems Objectives: To impart the skills needed to develop multimedia applications. Students will learn: z how to combine different media on a web application, z various audio and video formats, z multimedia software tools that helps in developing multimedia application. Sr. No. Topics 1. Multimedia: Meaning and its usage, Stages of a Multimedia Project & Multimedia Skills required in a team 2. Text: Fonts & Faces, Using Text in Multimedia, Font Editing & Design Tools, Hypermedia & Hypertext. 3. Sound: Multimedia System Sounds, Digital Audio, MIDI Audio, Audio File Formats, MIDI vs Digital Audio, Audio CD Playback. Audio Recording. Voice Recognition & Response. 4. Images: Still Images – Bitmaps, Vector Drawing, 3D Drawing & rendering, Natural Light & Colors, Computerized Colors, Color Palletes, Image File Formats, Macintosh & Windows Formats, Cross – Platform format. 5. Animation: Principle of Animations. Animation Techniques, Animation File Formats. 6. Video: How Video Works, Broadcast Video Standards: NTSC, PAL, SECAM, ATSC DTV, Analog Video, Digital Video, Digital Video Standards – ATSC, DVB, ISDB, Video recording & Shooting Videos, Video Editing, Optimizing Video files for CD-ROM, Digital display standards. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Investigation of bit patterned media, thermal flying height control sliders and heat assisted magnetic recording in hard disk drives Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3nd3d29b Author Zheng, Hao Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Investigation of Bit Patterned Media, Thermal Flying Height Control Sliders and Heat Assisted Magnetic Recording in Hard Disk Drives A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Engineering Sciences (Mechanical Engineering) by Hao Zheng Committee in charge: Professor Frank E. Talke, Chair Professor David J. Benson Professor Eric Fullerton Professor Philip E. Gill Professor Hidenori Murakami 2011 Copyright Hao Zheng, 2011 All rights reserved. This dissertation of Hao Zheng is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2011 iii to my parents Yanping Duan and Guangyuan Zheng iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ............................................................................................................... iii Dedication .................................................................................................................... iv Table of Contents .......................................................................................................... -

Psaudio Copper

Issue 133 MARCH 29TH, 2021 Copper has a new look! So does the rest of the PS Audio website, the result of countless hours of hard work. There's more functionality and easier access to articles, and additional developments will come. There will be some temporary glitches and some tweaks required – like high-end audio systems, magazines sometimes need tweaking too – but overall, we're excited to provide a better and more enjoyable reading experience. I now hand over the column to our esteemed Larry Schenbeck: Dear Copper Colleagues and Readers, Frank has graciously asked if I’d like to share a word or two about my intention to stop writing Too Much Tchaikovsky. So: thanks to everyone who read and enjoyed it – I wrote it for you. If you added comments occasionally, you made my day. I also wrote the column so I could keep learning, especially about emerging creatives and performers in classical music. Getting the chance to stumble upon something new and nourishing had sustained me in the academic world – it certainly wasn’t the money! – and I was grateful to continue that in Copper. So why stop? Because, as they say, there is a season. It has become considerably harder for me to stumble upon truly fresh sounds and then write freshly thereon. Here I am tempted to quote Douglas Adams or Satchel Paige, who both knew how to deliver an exit line. But I’ll just say (since Frank has promised to leave the light on), goodbye for now. The door is open, Larry, and we can’t thank you enough for your wonderful contributions. -

CED Digest, Vol. 7

************************************************************************ ************************************************************************ CED Digest Vol. 7 No. 1 1/5/2002 ------------------------------------------------------------------------ 20 Years Ago In CED History: January 6, 1982: * Archbishop Jozef Glemp, the Roman Catholic primate of Poland, tells a congregation in Warsaw's St. John's Cathedral that those who signed oaths renouncing Solidarity were coerced by the government and the oaths have no validity. January 7, 1982: * Presidential counselor Edwin Meese III reads a statement that reverses President Reagan's pre-election stand against the registration of 18-year-old males for a possible future military draft. * The Winter 1982 Consumer Electronics Show begins in Las Vegas, Nevada. While a year earlier the RCA VideoDisc system had been one of the most prominent introductions, at the 1982 show the VHD VideoDisc holds the spotlight with a large display space sporting the slogan "There's More to See on VHD." Other notable video-related introductions include the Technicolor CVC mini-cassette VCR system, the first tubeless consumer video camera, and the first Pioneer LaserDisc player with CX noise reduction. A picture of the VHD booth at the Winter 1982 CES can be seen at this URL: http://www.cedmagic.com/history/vhd-1982-ces.jpg January 8, 1982: * Spokesmen for the American Telephone & Telegraph Company (AT&T) and the U.S. Department of Justice announce the settlement of a seven-year-old antitrust case which will result in AT&T divesting itself of 22 telephone companies, effectively breaking up the monopoly. * Future CED title in widespread theatrical release: Four Friends. January 9, 1982: * A frigid blast of artic air arrives in the United States bringing with it a week of record low temperatures. -

Historical Development of Magnetic Recording and Tape Recorder 3 Masanori Kimizuka

Historical Development of Magnetic Recording and Tape Recorder 3 Masanori Kimizuka ■ Abstract The history of sound recording started with the "Phonograph," the machine invented by Thomas Edison in the USA in 1877. Following that invention, Oberlin Smith, an American engineer, announced his idea for magnetic recording in 1888. Ten years later, Valdemar Poulsen, a Danish telephone engineer, invented the world's frst magnetic recorder, called the "Telegraphone," in 1898. The Telegraphone used thin metal wire as the recording material. Though wire recorders like the Telegraphone did not become popular, research on magnetic recording continued all over the world, and a new type of recorder that used tape coated with magnetic powder instead of metal wire as the recording material was invented in the 1920's. The real archetype of the modern tape recorder, the "Magnetophone," which was developed in Germany in the mid-1930's, was based on this recorder.After World War II, the USA conducted extensive research on the technology of the requisitioned Magnetophone and subsequently developed a modern professional tape recorder. Since the functionality of this tape recorder was superior to that of the conventional disc recorder, several broadcast stations immediately introduced new machines to their radio broadcasting operations. The tape recorder was soon introduced to the consumer market also, which led to a very rapid increase in the number of machines produced. In Japan, Tokyo Tsushin Kogyo, which eventually changed its name to Sony, started investigating magnetic recording technology after the end of the war and soon developed their original magnetic tape and recorder. In 1950 they released the frst Japanese tape recorder. -

Manual of Analogue Sound Restoration Techniques

MANUAL OF ANALOGUE SOUND RESTORATION TECHNIQUES by Peter Copeland The British Library Analogue Sound Restoration Techniques MANUAL OF ANALOGUE SOUND RESTORATION TECHNIQUES by Peter Copeland This manual is dedicated to the memory of Patrick Saul who founded the British Institute of Recorded Sound,* and was its director from 1953 to 1978, thereby setting the scene which made this manual possible. Published September 2008 by The British Library 96 Euston Road, London NW1 2DB Copyright 2008, The British Library Board www.bl.uk * renamed the British Library Sound Archive in 1983. ii Analogue Sound Restoration Techniques CONTENTS Preface ................................................................................................................................................................1 Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................................................2 1 Introduction ..............................................................................................................................................3 1.1 The organisation of this manual ...........................................................................................................3 1.2 The target audience for this manual .....................................................................................................4 1.3 The original sound................................................................................................................................6 -

The Achievement of Television: the Quality and Features of John

Investigations into the Emergence of British Television 1926-1936 1 Investigations into the Emergence of British Television 1926-1936 November 2017 A Critical Review submitted to Aberystwyth University in partial fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD by Published Work) in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies Donald F McLean Aberystwyth University Investigations into the Emergence of British Television 1926-1936 2 Abstract This Critical Review discusses the significance of the author’s published works and their impact on the history of the emergence of British television between 1926 and 1936. Although events in television within this period have since been well- documented, the related debates have tended to be specialist in scope and restricted to technology-centric or institution-centric viewpoints. Within this period of complex, rapid technological change, the author’s published works introduce the principle of embracing multiple disciplines for comparative analysis. The author’s application of that principle opens up long- established views for further debate and provides a re-assessment of early British television within a broader context. The rewards of this approach are a view of events that not only avoids nationalistic bias and restrictions of a single institutional viewpoint, but also tackles the complex interdependencies of technology, of service provision and of content creation. These published works draw attention to the revolutionary improvements that enabled the BBC’s 1936 service and the re-definition of television, yet also emphasise the significance of the previous television broadcast services. The most important innovation within these works has been the author’s discovery and in-depth study of artefacts from that earlier period. -

The Makeover from DVD to Blu-Ray Disc

Praise for Blu-ray Disc Demystified “BD Demystified is an essential reference for designers and developers building with- in Blu-ray’s unique framework and provides them with the knowledge to deliver a compelling user experience with seamlessly integrated multimedia.” — Lee Evans, Ambient Digital Media, Inc., Marina del Rey, CA “Jim’s Demystified books are the definitive resource for anyone wishing to learn about optical media technologies.” — Bram Wessel, CTO and Co-Founder, Metabeam Corporation “As he did with such clarity for DVD, Jim Taylor (along with his team of experts) again lights the way for both professionals and consumers, pointing out the sights, warning us of the obstacles and giving us the lay of the land on our journey to a new high-definition disc format.” — Van Ling, Blu-ray/DVD Producer, Los Angeles, CA “Blu-ray Disc Demystified is an excellent reference for those at all levels of BD pro- duction. Everyone from novices to veterans will find useful information contained within. The authors have done a great job making difficult subjects like AACS encryption, BD-Java, and authoring for Blu-ray easy to understand.” — Jess Bowers, Director, Technical Services, 1K Studios, Burbank, CA “Like its red-laser predecessor, Blu-ray Disc Demystified will immediately take its rightful place as the definitive reference book on producing BD. No authoring house should undertake a Blu-ray project without this book on the author’s desk. If you are new to Blu-ray, this book will save you time, money, and heartache as it guides the DVD author through the new spec and production details of producing for Blu-ray.” — Denny Breitenfeld, CTO, NetBlender, Inc., Alexandria, VA “An all in one encyclopedia of all things BD.” — Robert Gekchyan, Lead Programmer/BD Technical Manager Technicolor Creative Services, Burbank, CA About the Authors Jim Taylor is chief technologist and general manager of the Advanced Technology Group at Sonic Solutions, the leading developer of BD, DVD, and CD creation software. -

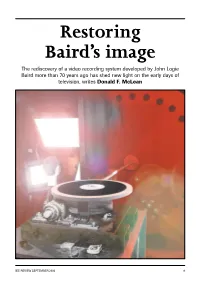

Restoring Baird's Image

Restoring Baird’s image The rediscovery of a video recording system developed by John Logie Baird more than 70 years ago has shed new light on the early days of television, writes Donald F. McLean IEE REVIEW SEPTEMBER 2000 9 t was just over 100 years ago, in August Television’s dawn 1900, that Constantin Perskyi presented a Spurred on by the discovery of the light paper entitled ‘Television’, making him the sensitivity of selenium in 1873, the early first person to use today’s well-worn word pioneers of ‘seeing at a distance’ demonstrated Ito describe the age-old dream of ‘seeing at a transmission and reception of still pictures over distance’. In October this year, it will be 75 years cable in the late 19th century without the since the first successful attempt to televise a live advantage of electronics. Fleming’s thermionic subject in light and shade. Coinciding with diode valve in 1904 and de Forest’s triode valve these anniversary commemorations, the IEE is and amplifier of 1912 started the electronic publishing a new book – ‘Restoring Baird’s revolution, essential for long distance imaging. Image’– which looks at the early history of By the early 1920s, news picture ‘facsimiles’, television and video recording in the light of some even using digital coding1, spanned some fascinating recent discoveries. Those thousands of miles. discoveries come from analysing and restoring In contrast to these slow, yet high-quality gramophone videodisc recordings made transmissions, television required several between 1927 and 1935, 25 years before the pictures per second to give the perception of first practical videotape recorder and nearly 50 motion. -

Sound Evidence: an Archaeology of Audio Recording and Surveillance in Popular Film and Media

Sound Evidence: An Archaeology of Audio Recording and Surveillance in Popular Film and Media by Dimitrios Pavlounis A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Screen Arts and Cultures) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Sheila C. Murphy, Chair Emeritus Professor Richard Abel Professor Lisa Ann Nakamura Associate Professor Aswin Punathambekar Professor Gerald Patrick Scannell © Dimitrios Pavlounis 2016 For My Parents ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My introduction to media studies took place over ten years ago at McGill University where Ned Schantz, Derek Nystrom, and Alanna Thain taught me to see the world differently. Their passionate teaching drew me to the discipline, and their continued generosity and support made me want to pursue graduate studies. I am also grateful to Kavi Abraham, Asif Yusuf, Chris Martin, Mike Shortt, Karishma Lall, Amanda Tripp, Islay Campbell, and Lees Nickerson for all of the good times we had then and have had since. Thanks also to my cousins Tasi and Joe for keeping me fed and laughing in Montreal. At the University of Toronto, my entire M.A. cohort created a sense of community that I have tried to bring with me to Michigan. Learning to be a graduate student shouldn’t have been so much fun. I am especially thankful to Rob King, Nic Sammond, and Corinn Columpar for being exemplary scholars and teachers. Never have I learned so much in a year. To give everyone at the University of Michigan who contributed in a meaningful way to the production of this dissertation proper acknowledgment would mean to write another dissertation-length document. -

Ur %Tic. Ikwriti•Geoibil. 6

, iL t t im MARIA GANDER JPL/UREI 8500 PALP OA PLY , NoRTHRIDGE CA 91329 " W rIt ci t ta • ;I A A i treauko, 1 • G-Sel 113 1 1 3 t t i r iI • 46-k ttig gigel t6' tl ' " a. F,Ctektreeritu ttmt ft*:311a. t t I t t I ! I l i ' I aI lii Ca- lki 4 h, le beAthe *b o w l* ur %tic. ikwriti•geoibil.it 4 3 0 01, 4 4 k WON 6 Itisheirirtrie r.. e.inne. 1 iterjt aittit rlail bliliff!.7i ..r 7-511 0itati,woftill.litli:_iii/r.5:11-1.1,11:i („ 5iIr --------,-:' ' ir t 1 tt ,k World's • .L most fir •mile ir`o• frequent - Shcwo Actual Irk Size er! Model ATI:15311/W Model AT853R Sure you'll see °the, brands hanging around from time to Quiet Please time, but when it comes to self- Our advanced electronics and supporting miniature condens- capsule design insure very lo% tern, and output from every ers, the Audio-Technica AT853 self-noise. Listen carefully to microphone in the a.:ea. You get seres, now in its foi_rth genera- ours and to theirs. You'll hear the same great sotmd above the tior., has been the Dver whehning theirs. And so will your criti- choir, mounted on a lectern, or chcice of both contractcrs and cal customers. used to reinforce rr,...sical instru- enc. users for years. ThE reason ments. Sound system operation is smple: It works s well. And New AT853R High Output and EQ are simplifi 3 d for superior, for some very impor:arr: reasons. -

I Lev Manovich the Language of New Media

I Lev Manovich The Language of New Media II To Norman Klein / Peter Lunenfeld / Vivian Sobchack III Table of Contents Prologue: Vertov’s Dataset.................................................................................VI Acknowledgments........................................................................................ XXVII Introduction ......................................................................................................... 30 A Personal Chronology........................................................................... 30 Theory of the Present.............................................................................. 32 Mapping New Media: the Method.......................................................... 34 Mapping New Media: Organization ....................................................... 36 The Terms: Language, Object, Representation ...................................... 38 I. What is New Media?........................................................................................ 43 Principles of New Media.............................................................................. 49 1. Numerical Representation................................................................... 49 2. Modularity .......................................................................................... 51 3. Automation ......................................................................................... 52 4. Variability ..........................................................................................