Contentious Corporate Social Responsibility Practices by British American Tobacco in Cameroon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 CO-OPERATION AGREEMENT Dated As of 27 September 2010

CO-OPERATION AGREEMENT dated as of 27 September 2010 among IMPERIAL TOBACCO LIMITED AND THE EUROPEAN UNION REPRESENTED BY THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION AND EACH MEMBER STATE LISTED ON THE SIGNATURE PAGES HERETO 1 ARTICLE 1 DEFINITIONS Section 1.1. Definitions........................................................................................... 7 ARTICLE 2 ITL’S SALES AND DISTRIBUTION COMPLIANCE PRACTICES Section 2.1. ITL Policies and Code of Conduct.................................................... 12 Section 2.2. Certification of Compliance.............................................................. 12 Section 2.3 Acquisition of Other Tobacco Companies and New Manufacturing Facilities. .......................................................................................... 14 Section 2.4 Subsequent changes to Affiliates of ITL............................................ 14 ARTICLE 3 ANTI-CONTRABAND AND ANTI-COUNTERFEIT INITIATIVES Section 3.1. Anti-Contraband and Anti-Counterfeit Initiatives............................ 14 Section 3.2. Support for Anti-Contraband and Anti-Counterfeit Initiatives......... 14 ARTICLE 4 PAYMENTS TO SUPPORT THE ANTI-CONTRABAND AND ANTI-COUNTERFEIT COOPERATION ARTICLE 5 NOTIFICATION AND INSPECTION OF CONTRABAND AND COUNTERFEIT SEIZURES Section 5.1. Notice of Seizure. .............................................................................. 15 Section 5.2. Inspection of Seizures. ...................................................................... 16 Section 5.3. Determination of Seizures................................................................ -

Chapter 10. Luso-Tropicalism Debunked, Again

chapter 10 Luso-tropicalism Debunked, Again Race, Racism, and Racialism in Three Portuguese-Speaking Societies Cristiana Bastos Luso-tropicalism’s Aft erlife and the Need for Further Research Th e term Luso-tropicalism was craft ed in the 1950s by the Brazilian anthropol- ogist and cultural historian Gilberto Freyre.1 In his earlier works on colonial Brazil, Freyre suggested that the Portuguese colonizers had a special ability to adapt to the tropics by easily intermingling, intermarrying, and interchanging cultural elements with diff erent peoples, given that they were themselves the result of multiple mixtures.2 Two decades later, he expanded the idea into a concept suitable to all societies sharing Portuguese infl uence, whether colonial plantations, settler societies, or conquest territories.3 Before Luso-tropicalism could mature—or expire—as a theory, it was bor- rowed for political purposes by the Portuguese government and pasted into the offi cial doctrine of the regime. Th e new doctrine, a combination of old imperial tropes and Freyre’s novel ideas, was propagated in the 1960s and early 1970s. At its core was the assertion of a benign, humanistic, and nonracist distinctive Portuguese character as best shown in the tropics. From that as- sumption followed the claims about empire not being an empire but a unique multiracial nation across the continents, and colonies not being colonies but parts of a singular nation that extended from Minho in Northern Portugal to distant Timor in Southeast Asia. Th ose rhetorical devices were meant to dismiss the challenges to the Portuguese colonial rule that came from three fronts: internal political opponents, African nationalist movements, and the United Nations. -

TOBACCO (To Be Filed by Manufacturers Who Do Not Participate in the Master Settlement Agreement) for Sales Made Within Michigan During the 2002 Calendar Year

ANNUAL CERTIFICATION OF COMPLIANCE FOR MANUFACTURER OF CIGARETTES AND/OR “ROLL-YOUR-OWN” TOBACCO (To be filed by manufacturers who do not participate in the Master Settlement Agreement) For sales made within Michigan during the 2002 calendar year Amendments in 2002 to the Tobacco Products Tax Act (1993 PA 327) support enforcement of the escrow requirements for tobacco product manufacturers who are not participating in the tobacco Master Settlement Agreement (1999 PA 244). The amendments require that non-participating manufacturers (NPM’s) provide to the State, and anyone who sells their cigarettes and/or ‘roll-your-own’ tobacco for consumption in Michigan, an annual certification of compliance. By providing the certification, they are attesting to the fact that they have met their escrow obligation under Act 244. The amendments prohibit anyone in Michigan from acquiring, possessing, or selling cigarettes and/or ‘roll-your-own’ tobacco manufactured by an NPM who has failed to provide the certification. The Act provides severe penalties for NPM’s, or anyone selling the cigarettes and/or ‘roll-your-own’ tobacco of NPM’s, for failure to comply with the requirements. The cigarettes, including ‘roll-your-own’ tobacco, of an NPM who has failed to provide the annual certification required by the Tobacco Products Tax Act are subject to seizure or confiscation from anyone in possession of them. If an NPM or any other person does not comply with these requirements, they may be subject to a civil fine not to exceed $1,000.00 per violation, in addition to other penalties that may be imposed under this act or the revenue act. -

Copyright by Per Ole Christian Steinert 2003

Copyright by Per Ole Christian Steinert 2003 Dissertation Committee for Per Ole Christian Steinert certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: ETHNIC COMMUNITIES AND ETHNO-POLITICAL STRATEGIES THE STRUGGLE FOR ETHNIC RIGHTS: A COMPARISON OF PERU, ECUADOR AND GUATEMALA Committee: Bryan Roberts, Supervisor Ronald Angel Robert Hummer Henry Selby Peter M. Ward ETHNIC COMMUNITIES AND ETHNO-POLITICAL STRATEGIES THE STRUGGLE FOR ETHNIC RIGHTS: A COMPARISON OF PERU, ECUADOR AND GUATEMALA by Per Ole Christian Steinert, M.A., Siv. Ing., Cand. Real. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2003 DEDICATION To independent thinking … If all mankind minus one, were of one opinion, and only one person were of a contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind (...) But the peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is, that it is robbing the human race; posterity as well as the existing generation; those who dissent from the opinion, still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth: if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error. J.S. Mill, On Liberty And to the person involved… The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood, who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions, and spends himself in a worthy cause; who at best, if he wins, knows the thrills of high achievements, and, if he fails, at least fails daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who know neither victory nor defeat. -

NVWA Nr. Merk/Type Nicotine (Mg/Sig) NFDPM (Teer)

NVWA nr. Merk/type Nicotine (mg/sig) NFDPM (teer) (mg/sig) CO (mg/sig) 89537347 Lexington 1,06 12,1 7,6 89398436 Camel Original 0,92 11,7 8,9 89398339 Lucky Strike Original Red 0,88 11,4 11,6 89398223 JPS Red 0,87 11,1 10,9 89399459 Bastos Filter 1,04 10,9 10,1 89399483 Belinda Super Kings 0,86 10,8 11,8 89398347 Mantano 0,83 10,8 7,3 89398274 Gauloises Brunes 0,74 10,7 10,1 89398967 Winston Classic 0,94 10,6 11,4 89399394 Titaan Red 0,75 10,5 11,1 89399572 Gauloises 0,88 10,5 10,6 89399408 Elixyr Groen 0,85 10,4 10,9 89398266 Gauloises Blondes Blue 0,77 10,4 9,8 89398886 Lucky Strike Red Additive Free 0,85 10,3 10,4 89537266 Dunhill International 0,94 10,3 9,9 89398932 Superkings Original Black 0,92 10,1 10,1 89537231 Mark 1 New Red 0,78 10 11,2 89399467 Benson & Hedges Gold 0,9 10 10,9 89398118 Peter Stuyvesant Red 0,82 10 10,9 89398428 L & M Red Label 0,78 10 10,5 89398959 Lambert & Butler Original Silver 0,91 10 10,3 89399645 Gladstone Classic 0,77 10 10,3 89398851 Lucky Strike Ice Gold 0,75 9,9 11,5 89537223 Mark 1 Green 0,68 9,8 11,2 89393671 Pall Mall Red 0,84 9,8 10,8 89399653 Chesterfield Red 0,75 9,8 10 89398371 Lucky strike Gold 0,76 9,7 11,1 89399599 Marlboro Gold 0,78 9,6 10,3 89398193 Davidoff Classic 0,88 9,6 10,1 89399637 Marlboro Red 100 0,79 9,6 9 89398878 Lucky Strike Ice 0,71 9,5 10,9 89398045 Pall Mall Red 0,81 9,5 10,5 89398355 Dunhill Master Blend Red 0,82 9,5 9,8 89399475 JPS Red 0,81 9,5 9,6 89398029 Marlboro Red 0,79 9,5 9 89537355 Elixyr Red 0,79 9,4 9,8 89398037 Marlboro Menthol 0,72 9,3 10,3 89399505 Marlboro -

Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology Working Papers

MAX PLANCK INSTITUTE FOR SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY WORKING PAPERS WORKING PAPER NO. 141 PATRICE LADWIG RICARDO ROQUE OLIVER TAppE CHRISTOPH KOHL CRISTIANA BASTOS FIELDWORK BETWEEN FOLDERS: FRAGMENTS, TRACES, AND THE RUINS OF COLONIAL ARCHIVES Halle / Saale 2012 ISSN 1615-4568 Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, PO Box 110351, 06017 Halle / Saale, Phone: +49 (0)345 2927- 0, Fax: +49 (0)345 2927- 402, http://www.eth.mpg.de, e-mail: [email protected] Fieldwork Between Folders: fragments, traces, and the ruins of colonial 1 archives Patrice Ladwig, Ricardo Roque, Oliver Tappe, Christoph Kohl, Cristiana Bastos2 Abstract This essay conceptualises the colonial archive as a product of processes of ruination. Taking its inspiration from recent studies of archival spaces, the three case studies on Portuguese, French, and Guinea-Bissauan colonial archives explore the ruptures, discontinuities, and silences inherent in such archives. With reference to Walter Benjamin’s writing of history and its recent applications in anthropology and history, the authors investigate the conditions, possibilities, and limitations of fieldwork in archives. Fragmentation, ruptures, and decay are not only understood as negative, but as productive processes. This perspective helps to shed light on the relevance of the historical materials that have survived as colonial debris and can provide traces that allow for developing unusual perspectives on the colonial past. By proposing methodologies to deal with these fragments, and by pointing to parallels in ethnographic fieldwork, the essay emphasises the processual character of data collection in the archive and the materials and documents themselves. Archives are, in this sense, less the static places of where facts lie waiting to be rescued, but places of the recurrent regrouping and transformation of facts through on-going ruination and fragment accumulation. -

Min Price 12-26-06

STATE OF ALASKA CIGARETTE PRESUMPTIVE MINIMUM PRICE EFFECTIVE 12/26/06 (Reflects price changes to Philip Morris USA brands) Section I: Cartons of Cigarettes with a 4.5% Wholesale Markup and a 6% Retail Markup BLUE & GRAY TAX STAMPS - 2006 Participating Manufacturers WHOLESALE RETAIL (A) (B) (C) (D) (E) (F) (G) (H) (I) (J) (K) (L) (M) (N) (O) (P) (Q) (R) Fairbanks City of Anchorage Fairbanks City of Juneau Mat-Su Valley Sitka Mat-Su Statewide Anchorage Borough Fairbanks Juneau Sitka Discounted Statewide Presumptive Borough Fairbanks Presumptive Presumptive Presumptive Valley Presumptive Presumptive Presumptive Presumptive Presumptive Presumptive Manufacturer Trade Discounted Manufacturer Presumptive Wholesale Presumptive Presumptive Wholesale Wholesale Wholesale Presumptive Retail Cost Retail Price Retail Price Retail Price Retail Price Retail Price Manufacturer / Brand Price Discount Price per Price + Alaska Wholesale Price Wholesale Price Wholesale Price Price Price Price Retail Price (Statewide (Anchorage (Fairbanks (City of (Juneau (Sitka per Carton per Carton Carton Tax Cost (Disc (Statewide (Statewide (Statewide (Statewide (Statewide (Statewide (Mat-Su Wholesale + Wholesale + Borough Fairbanks Wholesale + Wholesale + ($18.00/ctn) Mfr + 4.5%) Wholesale + Wholesale + Wholesale + Wholesale + Wholesale + Wholesale + Wholesale + 6%) 6%) Wholesale + Wholesale + 6%) 6%) $13.48/ctn) 8%) 16%) $3.00/ctn) $10.18/ctn) $10.00/ctn) 6%) 6%) 6%) ((D) + $13.48) (((C)x1.08)+$18) (((C)x1.16)+$18) ((D)+$3) ((D) + $10.18) ((D) + $10) (A) - (B) (C) + $18 (D) x 1.045 x 1.045 x 1.045 x 1.045 x 1.045 x 1.045 x1.045 (E) x 1.06 (F) x 1.06 (G) x 1.06 (H) x 1.06 (I) x 1.06 (J) x 1.06 (K) x 1.06 Caribbean - American Tobacco Corp. -

TNCO Levels and Ratio's

Canadian Intense method - ISO method - Ratio Canadian Intense/ISO Measured levels Declared levels Brand Tar Nicotine CO Tar Nicotine CO Tar Nicotine CO (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (CI/ISO) (CI/ISO) (CI/ISO) Marlboro Prime 26,1 1,7 40,0 1,0 0,1 2,0 26,1 17,2 20,0 Kent HD White 17,4 1,3 28,0 1,0 0,1 2,0 17,4 13,4 14,0 Peter Stuyvesant Silver 15,2 1,2 19,0 1,0 0,1 2,0 15,2 12,3 9,5 Karelia I 9,6 0,9 9,3 1,0 0,1 1,0 9,6 8,6 9,3 Davidoff Blue* 23,6 1,7 30,9 2,9 0,2 2,6 8,3 7,0 12,1 American Spirit Orange 20,5 2,1 18,4 3,0 0,4 4,0 6,8 5,1 4,6 Kent Surround Menthol 25,0 1,7 30,8 4,0 0,4 5,0 6,3 4,3 6,2 Marlboro Silver Blue 24,7 1,5 32,6 4,0 0,3 5,0 6,2 5,0 6,5 Karelia L (Blue) 17,6 1,7 14,1 3,0 0,3 2,0 5,9 5,6 7,1 Kent HD Silver 21,1 1,6 26,2 4,0 0,4 5,0 5,3 3,9 5,2 Peter Stuyvesant Blue* 20,2 1,6 21,7 4,0 0,4 5,0 5,1 4,7 4,3 Kent Surround Silver* 22,5 1,7 27,0 4,5 0,5 5,5 5,0 3,7 4,9 Templeton Blue 25,0 1,8 26,2 5,0 0,4 6,0 5,0 4,4 4,4 Belinda Filterkings 29,9 2,2 24,7 6,0 0,5 6,0 5,0 4,3 4,1 Silk Cut Purple 24,9 2,0 23,4 5,0 0,5 5,0 5,0 4,0 4,7 Boston White 23,3 1,6 25,3 5,0 0,3 6,0 4,7 5,5 4,2 Mark Adams No. -

Identifying Models of HIV Care and Treatment Service Delivery in Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia Using Cluster Analysis and Delphi Survey Sharon Tsui1*, Julie A

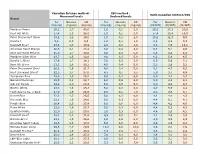

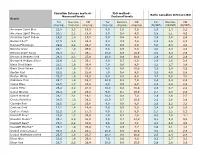

Tsui et al. BMC Health Services Research (2017) 17:811 DOI 10.1186/s12913-017-2772-4 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Identifying models of HIV care and treatment service delivery in Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia using cluster analysis and Delphi survey Sharon Tsui1*, Julie A. Denison1, Caitlin E. Kennedy1, Larry W. Chang1,2, Olivier Koole3,4, Kwasi Torpey5, Eric Van Praag6, Jason Farley2,7,8,9, Nathan Ford10, Leine Stuart11 and Fred Wabwire-Mangen12 Abstract Background: Organization of HIV care and treatment services, including clinic staffing and services, may shape clinical and financial outcomes, yet there has been little attempt to describe different models of HIV care in sub- Saharan Africa (SSA). Information about the relative benefits and drawbacks of different models could inform the scale-up of antiretroviral therapy (ART) and associated services in resource-limited settings (RLS), especially in light of expanded client populations with country adoption of WHO’s test and treat recommendation. Methods: We characterized task-shifting/task-sharing practices in 19 diverse ART clinics in Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia and used cluster analysis to identify unique models of service provision. We ran descriptive statistics to explore how the clusters varied by environmental factors and programmatic characteristics. Finally, we employed the Delphi Method to make systematic use of expert opinions to ensure that the cluster variables were meaningful in the context of actual task-shifting of ART services in SSA. Results: The cluster analysis identified three task-shifting/task-sharing models. The main differences across models were the availability of medical doctors, the scope of clinical responsibility assigned to nurses, and the use of lay health care workers. -

TNCO Levels and Ratio's

Canadian Intense method - ISO method - Ratio Canadian Intense/ISO Measured levels Declared levels Brand Tar Nicotine CO Tar Nicotine CO Tar Nicotine CO (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (mg/cig) (CI/ISO) (CI/ISO) (CI/ISO) American Spirit Blue 22,8 2,3 19,5 9,0 1,0 9,0 2,5 2,3 2,2 American Spirit Orange 20,5 2,1 18,4 3,0 0,4 4,0 6,8 5,1 4,6 American Spirit Yellow 19,5 1,8 17,0 5,0 0,6 6,0 3,9 3,0 2,8 Bastos Filter* 27,9 2,3 22,3 9,8 0,9 7,6 2,8 2,5 2,9 Belinda Filterkings 29,9 2,2 24,7 6,0 0,5 6,0 5,0 4,3 4,1 Belinda Green 24,1 1,9 25,6 6,0 0,5 6,0 4,0 3,9 4,3 Belinda Super Kings 36,3 2,7 29,5 10,0 0,8 10,0 3,6 3,4 2,9 Benson & Hedges Gold 28,3 2,3 27,9 10,0 0,9 10,0 2,8 2,6 2,8 Benson & Hedges Silver 22,6 1,8 25,1 8,0 0,7 9,0 2,8 2,5 2,8 Black Devil Black 23,1 1,6 30,4 7,0 0,6 9,0 3,3 2,7 3,4 Black Devil Yellow 25,4 1,8 31,6 8,0 0,6 10,0 3,2 2,9 3,2 Boston Red 23,2 1,6 25,4 7,0 0,4 9,0 3,3 4,0 2,8 Boston White 23,3 1,6 25,3 5,0 0,3 6,0 4,7 5,5 4,2 Caballero Plain 23,7 1,9 15,8 10,0 0,8 7,0 2,4 2,3 2,3 Camel Blue 22,5 1,7 23,8 8,0 0,6 9,0 2,8 2,8 2,6 Camel Filter 26,2 2,2 21,9 10,0 0,8 10,0 2,6 2,7 2,2 Camel Orange 24,4 1,9 23,6 9,0 0,7 10,0 2,7 2,8 2,4 Camel Original 28,1 2,1 19,1 10,0 0,8 7,0 2,8 2,6 2,7 Chesterfield Red 26,5 1,8 28,2 10,0 0,7 10,0 2,6 2,6 2,8 Claridge Red 22,6 1,3 26,6 8,0 0,6 8,0 2,8 2,2 3,3 Couture Gold 17,1 1,4 14,4 5,0 0,5 5,0 3,4 2,9 2,9 Couture Purple 21,2 1,8 17,3 8,0 0,7 8,0 2,7 2,5 2,2 Davidoff Blue* 23,6 1,7 30,9 2,9 0,2 2,6 8,3 7,0 12,1 Davidoff Classic* 29,1 2,4 31,0 9,5 0,7 10,4 3,1 3,3 3,0 Davidoff -

Delivering Quality Growth

OPERATING REVIEW DELIVERING QUALITY GROWTH OUR BRANDS GROWTH BRANDS The rest of our portfolio consists of Portfolio Brands; some of these are strong local brands that support our volume and revenue development, while others are delisted or migrated into Growth Brands. A number of migrations were completed in the year, as we continued to streamline our portfolio and improve our quality of growth. Total Group tobacco volumes were 255.5 billion stick equivalents (2017: 265.2 billion), with volumes down by 3.6 per cent, outperforming industry volume declines of 5.0 per cent. Growth Brands increased volume by 2.1 per cent and market share by 70 basis points, with share gains in all divisions. Excluding the benefit of brand migrations, Growth Brands also outperformed the industry. GROWTH BRANDS Full Year Result Change Constant 2018 2017 Actual Currency Market share % 9.2 8.5 +70 bps We achieved another Net revenue £m 3,799 3,690 +2.9% +3.9% Percentage of Group % 63.8 60.2 +360 bps excellent performance with volumes our Growth and Specialist Percentage of tobacco % 49.1 47.6 +150 bps & NGP net revenue Brands. These are the most important assets in our Growth Brands have broad consumer appeal and are comprised of: Davidoff, Gauloises Blondes, JPS, West, Lambert & Butler, portfolio and together they Bastos, Fine, Winston, News and Parker & Simpson. now account for 66.9 per cent Growth Brand volumes outperformed the market in the period of our tobacco & NGP net and net revenue grew by 3.9 per cent at constant currency. -

Mauritius: Poorer People Like Tough Warnings South

News analysis 365 is an answer: the skull and crossbones, not scholarship scheme for gifted young just familiar from the flags of cartoon pirate people to study at the University of ships, but widely used on containers of Mauritius may turn out not to have been poisonous chemicals and other dangerous money well spent. Tob Control: first published as on 29 November 2007. Downloaded from products and on electrical installations. Together with graphic images of diseased organs, the government included the skull South Africa: Swedish and crossbones in its wish list. But it was not to be. snus snare British American Tobacco (BAT) recently In a lengthy period of debate, it emerged sent a delegation of South African mem- that the tobacco industry did not just bers of parliament to Sweden on a ‘‘fact oppose disease-related graphic warnings Mauritius: cigarettes marked with a skull and crossbones received overwhelming approval in a finding’’ trip, to learn about the blessings (though some more than others) but was survey, even by smokers. of snus oral tobacco. The trip was particularly desperate to prevent the skull organised by a group called the and crossbones from appearing. This may having a skull and crossbones on cigar- Association of Reduction of Tobacco- at first sight appear surprising, but the ette packs, as well as on each individual related Harm (ARTH). manufacturers of bidis, the leaf-wrapped, cigarette, is Mauritius. Health organisa- When a draft programme came to light local product used by millions of lower tion ViSa carried out a detailed survey just two weeks before the start of the trip, income smokers, were especially desperate with people visiting prison inmates, it revealed that the snus manufacturer to prevent the government imposing a which among other benefits got Swedish Match and other pro-snus pro- warning that was particularly effective at responses from a sample of the country’s moters were to entertain members of the reaching their customers.