The Dance Scene and the Processes of the Aesthetic Transgression of the Body

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transitions Dance Company

PRESS RELEASE Send date Transitions Dance Company: Triple Bill Trinity Laban’s leading student training company showcases dancers in three brand new works from established choreographers Choreographed by Dog Kennel Hill Project, Theo Clinkard and Ederson Rodrigues Xavier UK Tour 19 February – 27 May “Performances by this enterprising company are always an eye-opener.” (Guardian Guide) Transitions Dance Company’s triple bill showcases the next generation of contemporary dance performers from Trinity Laban with twelve MA students performing three brand new pieces from choreographers Dog Kennel Hill Project, Theo Clinkard and Ederson Rodrigues Xavier. Since it was founded in 1982 by original Martha Graham Dance Company member Bonnie Bird, this pioneering company has aimed to bridge the gap between training and a professional performance career for graduate dancers. Transitions Dance Company aims to allow company members to gain practical experience of life in a touring dance company whilst simultaneously completing their MA Dance Performance. Past alumni of the company include distinguished artists such as Sir Matthew Bourne (New Adventures), Luca Silvestrini (Luca Silvestrini’s Protein), and Emma Gladstone (Artistic Director and Chief Executive of Dance Umbrella). Fieldwork from performance and research collective Dog Kennel Hill Project explores how, as a newly formed company, the dancers locate themselves now and in relation to their past. Through a deconstructed series of arrivals and departures and a language of stumbles, false starts, surges and going round in circles, Fieldwork asks “when do we truly arrive anywhere?” my dance, your touch draws upon research that outlines how physical touch affects our behavioural, cultural, emotional and biological development. -

Premieres on the Cover People

PDL_REGISTRATION_210x297_2017_Mise en page 1 01.06.17 10:52 Page1 Premieres 18 Bertaud, Valastro, Bouché, BE PART OF Paul FRANÇOIS FARGUE weighs up four new THIS UNIQUE ballets by four Paris Opera dancers EXPERIENCE! 22 The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas MIKE DIXON considers Daniel de Andrade's take on John Boyne's wartime novel 34 Swan Lake DEBORAH WEISS on Krzysztof Pastor's new production that marries a slice of history with Reece Clarke. Photo: Emma Kauldhar the traditional story P RIX 38 Ballet of Difference On the Cover ALISON KENT appraises Richard Siegal's new 56 venture and catches other highlights at Dance INTERNATIONAL BALLET COMPETITION 2017 in Munich 10 Ashton JAN. 28 TH – FEB. 4TH, 2018 AMANDA JENNINGS reviews The Royal DE Ballet's last programme in London this Whipped Cream 42 season AMANDA JENNINGS savours the New York premiere of ABT's sweet confection People L A U S ANNE 58 Dangerous Liaisons ROBERT PENMAN reviews Cathy Marston's 16 Zenaida's Farewell new ballet in Copenhagen MIKE DIXON catches the live relay from the Royal Opera House 66 Odessa/The Decalogue TRINA MANNINO considers world premieres 28 Reece Clarke by Alexei Ratmansky and Justin Peck EMMA KAULDHAR meets up with The Royal Ballet’s Scottish first artist dancing 70 Preljocaj & Pite principal roles MIKE DIXON appraises Scottish Ballet's bill at Sadler's Wells 49 Bethany Kingsley-Garner GERARD DAVIS catches up with the Consort and Dream in Oakland 84 Scottish Ballet principal dancer CARLA ESCODA catches a world premiere and Graham Lustig’s take on the Bard’s play 69 Obituary Sergei Vikharev remembered 6 ENTRE NOUS Passing on the Flame: 83 AUDITIONS AND JOBS 78 Luca Masala 101 WHAT’S ON AMANDA JENNINGS meets the REGISTRATION DEADLINE contents 106 PEOPLE PAGE director of Academie de Danse Princesse Grace in Monaco Front cover: The Royal Ballet - Zenaida Yanowsky and Roberto Bolle in Ashton's Marguerite and Armand. -

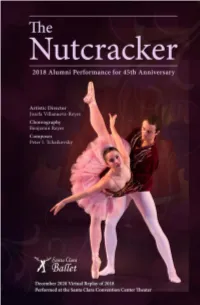

2018 Alumni Performance 45Th Anniversary Show Program

A Message from Josefa Villanueva-Reyes, Artistic Director and Founder: I welcome you with great joy and happiness to celebrate the Santa Clara Ballet’s 45th Anniversary of the Nutcracker Ballet. The Santa Clara Ballet continues the legacy left to us by our late Director and choreographer, Benjamin Reyes, by sharing this favorite family Christmas Ballet with our community, our student and professional dancers and our loyal supporters. The Company’s roots started right here in Santa Clara, and has continued despite the usual problems of obtaining funding and support. We can continue because of all of you who are present in our performances, and through your generous donations and volunteer work. The Company continues its work in spreading the awareness and the love of dance to warm families and contribute to the quality of life of the community. For this Sunday’s performance of our 45th Annual Nutcracker, the stage will be graced by our Alumni who serve as a testament to the success of the company’s influence to the community and the world beyond. Thank you for your presence today and please continue to join us on our journey. Josefa Reyes JOSEFA VILLANUEVA-REYES started her training in the Philippines with Roberta and Ricardo Cassell (a student of Vincenzo Celli). She was formerly a member of the San Francisco Ballet Company and the San Francisco Opera Ballet. Previous to that, she performed as a principal dancer with the San Francisco Ballet Celeste for four years. Her performing experience included multiple lead roles from the classical repertory. Villanueva-Reyes taught at the San Francisco Conservatory of Ballet and Theatre Arts as well as San Jose City College. -

Queensland Ballet

Queensland Front cover: Rachael Walsh as Fonteyn & Christian Tátchev as Nureyev dance The Lady of the Camellias pas de deux in François Klaus’s Fonteyn Remembered; Photographer: Ken Sparrow Below: Sarah Thompson and children taking class at the Open Day BAllet ANNuAl REPORT 2010 Queensland Ballet Thomas Dixon Centre Cnr Drake St & Montague Rd West End Queensland 4101 Australia Phone: 07 3013 6666 Fax: 07 3013 6600 Email: [email protected] Web: www.queenslandballet.com.au Christian Tátchev and Keian langdon in François Klaus’s Don Quixote (excerpt), 50th Anniversary International Gala; Photographer: Ken Sparrow Christian Tátchev as Romeo & Rachael Walsh as Juliet in François Klaus’s Romeo & Juliet; Photographer: Ken Sparrow Queensland Ballet 2010 AnnuAl RepoRt CONTENTS Company profile 1 2010 highlights 2 50 year chronology 3 Chair’s review 7 Artistic Director’s report 8 Chief Executive Officer’s report 10 2010 performance summary 11 The Company 15 Acknowledgements 17 Directors’ report 19 Lead Auditor’s Independence Declaration 25 Financial report 26 Independent auditor’s report 41 Appendix A: 2010 strategic performance 42 Appendix B: Queensland Ballet Friends 44 QUEENSlAnD BALLET 1 COMPANY PROFILE Queensland Ballet is the advanced dance training to students in ouR DReAm Years 10, 11, and 12 at Kelvin Grove State flagship ballet company of the College as well as the introductory Track By 2013, Queensland Ballet will be State of Queensland, with a Dance and Mid-Trackdance programs for recognised, not only in Queensland but reputation for a fresh, energetic Years 3 to 9. throughout Australia and also overseas, for: and eclectic repertoire ranging Community education and outreach is » creating and presenting a broad from short works for children to achieved through a range of programs. -

Forever • UK 5,00 £ Switzerland 8,00 CHF USA $ Canada 7,00 $; (Euro Zone)

edition ENGLISH n° 284 • the international DANCE magazine TOM 650 CFP) Pina Forever • UK 5,00 £ Switzerland 8,00 CHF USA $ Canada 7,00 $; (Euro zone) € 4,90 9 10 3 4 Editor-in-chief Alfio Agostini Contributors/writers the international dance magazine Erik Aschengreen Leonetta Bentivoglio ENGLISH Edition Donatella Bertozzi Valeria Crippa Clement Crisp Gerald Dowler Marinella Guatterini Elisa Guzzo Vaccarino Marc Haegeman Anna Kisselgoff Dieudonné Korolakina Kevin Ng Jean Pierre Pastori Martine Planells Olga Rozanova On the cover, Pina Bausch’s final Roger Salas work (2009) “Como el musguito en Sonia Schoonejans la piedra, ay, sí, sí, sí...” René Sirvin dancer Anna Wehsarg, Tanztheater Lilo Weber Wuppertal, Santiago de Chile, 2009. Photo © Ninni Romeo Editorial assistant Cristiano Merlo Translations Simonetta Allder Cristiano Merlo 6 News – from the dance world Editorial services, design, web Luca Ruzza 22 On the cover : Advertising Pina Forever [email protected] ph. (+33) 09.82.29.82.84 Bluebeard in the #Metoo era (+39) 011.19.58.20.38 Subscriptions 30 On stage, critics : [email protected] The Royal Ballet, London n° 284 - II. 2020 Les Ballets de Monte-Carlo Hamburg Ballet: “Duse” Hamburg Ballet, John Neumeier Het Nationale Ballet, Amsterdam English National Ballet Paul Taylor Dance Company São Paulo Dance Company La Scala Ballet, Milan Staatsballett Berlin Stanislavsky Ballet, Moscow Cannes Jeune Ballet Het Nationale Ballet: “Frida” BALLET 2000 New Adventures/Matthew Bourne B.P. 1283 – 06005 Nice cedex 01 – F tél. (+33) 09.82.29.82.84 Teac Damse/Keegan Dolan Éditions Ballet 2000 Sarl – France 47 Prix de Lausanne ISSN 2493-3880 (English Edition) Commission Paritaire P.A.P. -

People Performances Features

« Songs for a Siren 20 » PREMIERES PEER GYNT Ian Whalen, Huston Thomas in photography: Johan Inger PLAYLIST George Balanchine/Crystal Pite/ William Forsythe Academia Annarella - Francisco Gomes, Pedro Marques, Antonio Casalinho and Giulio Diligente in Anton Dolin's Variations for 4. © Enrique Perez-Cancio Cantero FOUR LAST SONGS Ballett George Balanchine/ Hans van Manen/David Dawson People Thierry Malandain 20 Jacob O'Connell performing at DistDancing. © Emma Kauldhar FRANÇOIS FARGUE talks with the French director/choreographer about President REPERTOIRE Macron's controversial comments and Features the current situation in France 32 Where We're At SEMPER ESSENCE: 26 George Liang EMMA KAULDHAR asked nine artistic WE WILL DANCE! GERARD DAVIS catches up with the directors to share their creative strategies A gala with the Semperoper Ballett Northern Ballet dancer for the 2020-21 season Semperoper INGRID LORENTZEN Performances JEAN-CHRISTOPHE MAILLOT THE NUTCRACKER ERIC GAUTHIER Aaron S. Watkin & Jason Beechey Stuttgart BEN VAN CAUWENBERGH 12 TED BRANDSEN ALISON KENT sees Stuttgart Ballet back on LINNAR LOORIS SWAN LAKE stage with three premieres KRZYSZTOF PASTOR Aaron S. Watkin AARON S. WATKIN DistDancing 16 MIKKO NISSINEN EMMA KAULDHAR asks Chisato Katsura how the project and open-air performances came information & tickets semperoper.de about Masks and the Dance 43 MIKE DIXON looks at the long association Petit Pas of masks with dance and theatre 24 ALISON KENT applauds the Bayerisches Staatsballett's return to the stage with an The Dance -

Abstracts № 41 on the 100-Th Anniversary of V. M. Krasouskaya

Abstracts № 41 On the 100-th anniversary of V. M. Krasouskaya B. A. Illarionov V. M. Krasovskaya and the Vaganova Ballet Academy The article contains the story of scientific work of V.M. Krasovskaya who was an outstanding ballet researcher, member of Leningrad Choreographic School (Vaganova Ballet Academy). The article establishes starting date of her literary activities as a professor of the ballet history, reveals facts and details of work and revival of the Department of the theory and history of ballet. It also evaluates significance of Krasovskaya research file cabinet. Keywords: V.M. Krasovskaya, Leningrad Choreographic School, Vaganova Ballet Academy, theory and history of ballet, Department of the theory and history of ballet. L. I. Abyzova V. M. Krasovskaya - a pioneer of the ballet review Article is devoted to one of the areas of multifaceted creativity of V.M. Krasovskaya. Outstanding ballet researcher, she becomes a true innovator in a rare genre of ballet criticism - a genre of the overview of ballet seasons. The article describes and analyzes «Leningrad ballet companies seasonal reviews» for years 1954-61. Prominent features of V.M. Krasovskaya's critical method, defined by fusion of information, intelligence and artistry of presentation, are marked. The author reintroduces almost forgotten work of V.M. Krasovskaya, paying attention to its current relevance. Keywords: V.M. Krasovskaya; Yuri Grigorovich; Igor Belsky, ballet criticism; Kirov State Academic Opera and Ballet Theater, Mariinsky Theater; Maly Opera Theater; Leningrad Ballet School;. L. V. Grabova Overview of the documents from a personal archive fund of V.M. Krasovskaya stored in the Central State Archive of Literature and Arts of St. -

A Study on the Gender Imbalance Among Professional Choreographers Working in the Fields of Classical Ballet and Contemporary Dance

Where are the female choreographers? A study on the gender imbalance among professional choreographers working in the fields of classical ballet and contemporary dance. Jessica Teague August 2016 This Dissertation is submitted to City University as part of the requirements for the award of MA Culture, Policy and Management 1 Abstract The dissertation investigates the lack of women working as professional choreographers in both the UK and the wider international dance sector. Although dance as an art form within western cultures is often perceived as ‘the art of women,’ it is predominately men who are conceptualising the works and choreographing the movement. This study focuses on understanding the phenomenon that leads female choreographers to be less likely to produce works for leading dance companies and venues than their male counterparts. The research investigates the current scope of the gender imbalance in the professional choreographic field, the reasons for the imbalance and provides theories as to why the imbalance is more pronounced in the classical ballet sector compared to the contemporary dance field. The research draws together experiences and statistical evidence from two significant branches of the artistic process; the choreographers involved in creating dance and the Gatekeepers and organisations that commission them. Key issues surrounding the problem are identified and assessed through qualitative data drawn from interviews with nine professional female choreographers. A statistical analysis of the repertoire choices of 32 leading international dance companies quantifies and compares the severity of the gender imbalance at the highest professional level. The data indicates that the scope of the phenomenon affects not only the UK but also the majority of the Western world. -

Symphonie Fantastique Was the Catalyst for an Equally Passionate Ballet

Madeleine Eastoe, Robert Curran and Remi Wörtmeyer in Symphonie Fantasique Photography—Jim McFarlane Kirsty Martin and Robert Curran in Symphonie Fantasique Symphonie Photography—Justin Smith Fantastique Described as “the first psychedelic musical trip”, Hector Berlioz’s passionate Symphonie Fantastique was the catalyst for an equally passionate ballet. By Valerie Lawson. In Paris, Hector Berlioz fell in love with his beloved’s death, then is swept up in an The balletic adaptation of Symphonie Both critics and audiences loved the the idea of love. His infatuation led to orgy with a coven of witches and evil spirits. Fantastique had to wait for more than a production which was chosen by public the creation of a revolutionary symphony century, when Massine was experimenting ballot to be part of the programme for that ushered in the Romantic age of the The symphony predicted the bleak end of with the then-controversial idea of using the company’s last performance on that nineteenth century. The symphony was an Berlioz’s eventual life with Smithson. They symphonic music for ballet. That year, tour. Symphonie Fantastique returned to artistic triumph, both in the concert hall and married in 1833 but the couple broke up for Colonel de Basil’s Ballets Russes, he Australia during the Original Ballet Russe much later, at The Royal Opera House in eight years later. A document in the Clare choreographed Les Présages to Tchaikovsky’s tour, with the leading roles danced in 1940 Covent Garden where it came to life visually in County Library in Ireland explains how the Symphony No. -

1 Giselle the Australian Ballet

THE AUSTRALIAN BALLET GISELLE 1 Lifting them higher Telstra is supporting the next generation of rising stars through the Telstra Ballet Dancer Award. Telstra and The Australian Ballet, partners since 1984. 2018 Telstra Ballet Dancer Award Winner, Jade Wood | Photographer: Lester Jones 2 THE AUSTRALIAN BALLET 2019 SEASON Lifting them higher Telstra is supporting the next generation of rising stars through the Telstra Ballet Dancer Award. Telstra and The Australian Ballet, partners since 1984. 1 – 18 MAY 2019 | SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE Government Lead Principal 2018 Telstra Ballet Dancer Award Winner, Jade Wood | Photographer: Lester Jones Partners Partners Partner Cover: Dimity Azoury. Photography Justin Ridler Above: Ako Kondo. Photography Lynette Wills Richard House, Valerie Tereshchenko and Amber Scott. Photography Lynette Wills 4 THE AUSTRALIAN BALLET 2019 SEASON NOTE FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Giselle has a special place in The Australian Ballet’s history, and has been a constant in our repertoire since the company’s earliest years. The superstars Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev danced it with us in 1964, in a production based on the Borovansky Ballet’s. Our founding artistic director, Peggy van Praagh, created her production in 1965; it premiered in Birmingham on the company’s first international tour, and won a Grand Prix for the best production staged in Paris that year. It went on to become one of the most frequently performed ballets in our repertoire. Peggy’s production came to a tragic end when the scenery was consumed by fire on our 1985 regional tour. The artistic director at the time, Maina Gielgud, created her own production a year later. -

Lithuanian Dance Scene'12

Lithuanian DanceScene 2012 Birutė Banevičiūtė Puzzle 5 Amos Ben-Tal Kill the Victor 5 Rūta Butkus Lost Eyes 7 5g of Hope 7 Loreta Juodkaitė Mirage 9 Inga Kuznecova & Petras Lisauskas And Everything Went Very Well 9 Birutė Letukaitė The Sea 11 Sonus.Lux.Unum 11 Petras Lisauskas YOUME 13 Jérôme Meyer & Isabelle Chaffaud 3 W(o)men 13 s t n Krzysztof Pastor e t n o Tristan and Isolde 15 C Agnija Šeiko No Space at the Parking Lot 15 Juliets 17 Marija Simona Šimulynaitė Sunstroke 17 Brigita Urbietytė Tango Salon 19 Austėja Vilkaitytė Dear Lithuania 19 Festivals & Projects 20 Organizations & Companies 24 Contacts 30 PUZZLE © DIMITRIJ MATVEJEV Puzzle Kill the Victor DANSEMA DANCE THEATRE, Vilnius AURA DANCE THEATRE, Kaunas KORZO PRODUCTIONS, The Hague Choreography Birutė Banevičiūtė | Dance Giedrė Subotinaitė, Indrė Bacevičiūtė, Choreography, music & text Amos Ben-Tal | Mantas Stabačinskas | Music Rasa Dikčienė | Dance Gotautė Kalmatavičiūtė, Marius Pinigis, Light design Aurelijus Davidavičius | Lana Coporda (Ema Nedobežkina, understudy) | Consultation Ingrida Gerbutavičiūtė Costumes Amos Ben-Tal | Light design Amos Ben-Tal, Peter Lemmens Duration 35' | Première 2012 Duration 15' | Première 2012 Puzzle is the first contemporary dance per- formance in Lithuania for 0-3 years old chil- 64 square-meters, a box in a box, dren. Knowing that children can concen- 2 females, 1 male, glistening skin, shiny ė t trate their attention just for few minutes, metal, a pulse, a voice, a word. Now what? ū i č there is alternated watching to the action i v e and movement during the performance. An AURA Dance Theatre commissioned the Is- n A B especially composed music offers simple raeli choreographer Amos Ben-Tal to create ė t u and high sound combinations suitable for a short piece for the company. -

Dance Brochure

Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Limited Dance 2006 Edition Also see www.boosey.com/downloads/dance06icolour.pdf Figure drawings for a relief mural by Ivor Abrahams (courtesy Bernard Jacobson Gallery) The Boosey & Hawkes catalogue contains many of the most significant and popular scores in the dance repertoire, including original ballets (see below) and concert works which have received highly successful choreographies (see page 9). To hear some of the music, a free CD sampler is available upon request. Works written as ballets composer work, duration and scoring background details Andriessen Odyssey 75’ Collaboration between Beppie Blankert and Louis Andriessen 4 female singers—kbd sampler based on Homer’s Odyssey and James Joyce’s Ulysses. Inspired by a fascination with sensuality and detachment, the ballet brings together the ancient, the old and the new. Original choreography performed with four singers, three dancers and one actress. Argento The Resurrection of Don Juan 45’ Ballet in one act to a scenario by Richard Hart, premiered in 1955. 2(II=picc).2.2.2—4.2.2.1—timp.perc:cyms/tgl/BD/SD/tamb— harp—strings Bernstein The Dybbuk 50’ First choreographed by Jerome Robbins for New York City Ballet 3.3.4.3—4.3.3.1—timp.perc(3)—harp—pft—strings—baritone in 1974. It is a ritualistic dancework drawing upon Shul Ansky’s and bass soli famous play, Jewish folk traditions in general and the mystical symbolism of the kabbalah. The Robbins Dybbuk invites revival, but new choreographies may be created using a different title. Bernstein Facsimile 19’ A ‘choreographic essay’ dedicated to Jerome Robbins and 2(II=picc).2.2(=Ebcl).2—4.2.crt.2.1—timp.perc(2)— first staged at the Broadway Theatre in New York in 1946.