Entrepreneurship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Manufacturing Affiliates in Europe and Turkey

06-ORD 70H-002AA 7 Japanese Manufacturing Affiliates in Europe and Turkey - 2005 Survey - September 2006 Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) Preface The survey on “Japanese manufacturing affiliates in Europe and Turkey” has been conducted 22 times since the first survey in 1983*. The latest survey, carried out from January 2006 to February 2006 targeting 16 countries in Western Europe, 8 countries in Central and Eastern Europe, and Turkey, focused on business trends and future prospects in each country, procurement of materials, production, sales, and management problems, effects of EU environmental regulations, etc. The survey revealed that as of the end of 2005 there were a total of 1,008 Japanese manufacturing affiliates operating in the surveyed region --- 818 in Western Europe, 174 in Central and Eastern Europe, and 16 in Turkey. Of this total, 291 affiliates --- 284 in Western Europe, 6 in Central and Eastern Europe, and 1 in Turkey --- also operate R & D or design centers. Also, the number of Japanese affiliates who operate only R & D or design centers in the surveyed region (no manufacturing operations) totaled 129 affiliates --- 125 in Western Europe and 4 in Central and Eastern Europe. In this survey we put emphasis on the effects of EU environmental regulations on Japanese manufacturing affiliates. We would like to express our great appreciation to the affiliates concerned for their kind cooperation, which have enabled us over the years to constantly improve the survey and report on the results. We hope that the affiliates and those who are interested in business development in Europe and/or Turkey will find this report useful. -

FTSE Japan ESG Low Carbon Select

2 FTSE Russell Publications 19 August 2021 FTSE Japan ESG Low Carbon Select Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 30 June 2021 Constituent Index weight (%) Country Constituent Index weight (%) Country Constituent Index weight (%) Country ABC-Mart 0.01 JAPAN Ebara 0.17 JAPAN JFE Holdings 0.04 JAPAN Acom 0.02 JAPAN Eisai 1.03 JAPAN JGC Corp 0.02 JAPAN Activia Properties 0.01 JAPAN Eneos Holdings 0.05 JAPAN JSR Corp 0.11 JAPAN Advance Residence Investment 0.01 JAPAN Ezaki Glico 0.01 JAPAN JTEKT 0.07 JAPAN Advantest Corp 0.53 JAPAN Fancl Corp 0.03 JAPAN Justsystems 0.01 JAPAN Aeon 0.61 JAPAN Fanuc 0.87 JAPAN Kagome 0.02 JAPAN AEON Financial Service 0.01 JAPAN Fast Retailing 3.13 JAPAN Kajima Corp 0.1 JAPAN Aeon Mall 0.01 JAPAN FP Corporation 0.04 JAPAN Kakaku.com Inc. 0.05 JAPAN AGC 0.06 JAPAN Fuji Electric 0.18 JAPAN Kaken Pharmaceutical 0.01 JAPAN Aica Kogyo 0.07 JAPAN Fuji Oil Holdings 0.01 JAPAN Kamigumi 0.01 JAPAN Ain Pharmaciez <0.005 JAPAN FUJIFILM Holdings 1.05 JAPAN Kaneka Corp 0.01 JAPAN Air Water 0.01 JAPAN Fujitsu 2.04 JAPAN Kansai Paint 0.05 JAPAN Aisin Seiki Co 0.31 JAPAN Fujitsu General 0.01 JAPAN Kao 1.38 JAPAN Ajinomoto Co 0.27 JAPAN Fukuoka Financial Group 0.01 JAPAN KDDI Corp 2.22 JAPAN Alfresa Holdings 0.01 JAPAN Fukuyama Transporting 0.01 JAPAN Keihan Holdings 0.02 JAPAN Alps Alpine 0.04 JAPAN Furukawa Electric 0.03 JAPAN Keikyu Corporation 0.02 JAPAN Amada 0.01 JAPAN Fuyo General Lease 0.08 JAPAN Keio Corp 0.04 JAPAN Amano Corp 0.01 JAPAN GLP J-REIT 0.02 JAPAN Keisei Electric Railway 0.03 JAPAN ANA Holdings 0.02 JAPAN GMO Internet 0.01 JAPAN Kenedix Office Investment Corporation 0.01 JAPAN Anritsu 0.15 JAPAN GMO Payment Gateway 0.01 JAPAN KEWPIE Corporation 0.03 JAPAN Aozora Bank 0.02 JAPAN Goldwin 0.01 JAPAN Keyence Corp 0.42 JAPAN As One 0.01 JAPAN GS Yuasa Corp 0.03 JAPAN Kikkoman 0.25 JAPAN Asahi Group Holdings 0.5 JAPAN GungHo Online Entertainment 0.01 JAPAN Kinden <0.005 JAPAN Asahi Intecc 0.01 JAPAN Gunma Bank 0.01 JAPAN Kintetsu 0.03 JAPAN Asahi Kasei Corporation 0.26 JAPAN H.U. -

Gamewith / 6552

GameWith / 6552 COVERAGE INITIATED ON: 2019.09.27 LAST UPDATE: 2021.04.19 Shared Research Inc. has produced this report by request from the company discussed in the report. The aim is to provide an “owner’s manual” to investors. We at Shared Research Inc. make every effort to provide an accurate, objective, and neutral analysis. In order to highlight any biases, we clearly attribute our data and findings. We will always present opinions from company management as such. Our views are ours where stated. We do not try to convince or influence, only inform. We appreciate your suggestions and feedback. Write to us at [email protected] or find us on Bloomberg. Research Coverage Report by Shared Research Inc. GameWith / 6552 RCoverage LAST UPDATE: 2021.04.19 Research Coverage Report by Shared Research Inc. | https://sharedresearch.jp INDEX How to read a Shared Research report: This report begins with the trends and outlook section, which discusses the company’s most recent earnings. First-time readers should start at the business section later in the report. Executive summary ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Key financial data ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 Recent updates ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 Highlights ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ -

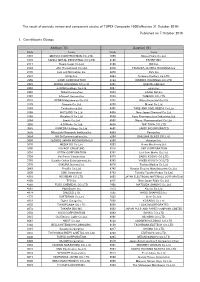

Published on 7 October 2016 1. Constituents Change the Result Of

The result of periodic review and component stocks of TOPIX Composite 1500(effective 31 October 2016) Published on 7 October 2016 1. Constituents Change Addition( 70 ) Deletion( 60 ) Code Issue Code Issue 1810 MATSUI CONSTRUCTION CO.,LTD. 1868 Mitsui Home Co.,Ltd. 1972 SANKO METAL INDUSTRIAL CO.,LTD. 2196 ESCRIT INC. 2117 Nissin Sugar Co.,Ltd. 2198 IKK Inc. 2124 JAC Recruitment Co.,Ltd. 2418 TSUKADA GLOBAL HOLDINGS Inc. 2170 Link and Motivation Inc. 3079 DVx Inc. 2337 Ichigo Inc. 3093 Treasure Factory Co.,LTD. 2359 CORE CORPORATION 3194 KIRINDO HOLDINGS CO.,LTD. 2429 WORLD HOLDINGS CO.,LTD. 3205 DAIDOH LIMITED 2462 J-COM Holdings Co.,Ltd. 3667 enish,inc. 2485 TEAR Corporation 3834 ASAHI Net,Inc. 2492 Infomart Corporation 3946 TOMOKU CO.,LTD. 2915 KENKO Mayonnaise Co.,Ltd. 4221 Okura Industrial Co.,Ltd. 3179 Syuppin Co.,Ltd. 4238 Miraial Co.,Ltd. 3193 Torikizoku co.,ltd. 4331 TAKE AND GIVE. NEEDS Co.,Ltd. 3196 HOTLAND Co.,Ltd. 4406 New Japan Chemical Co.,Ltd. 3199 Watahan & Co.,Ltd. 4538 Fuso Pharmaceutical Industries,Ltd. 3244 Samty Co.,Ltd. 4550 Nissui Pharmaceutical Co.,Ltd. 3250 A.D.Works Co.,Ltd. 4636 T&K TOKA CO.,LTD. 3543 KOMEDA Holdings Co.,Ltd. 4651 SANIX INCORPORATED 3636 Mitsubishi Research Institute,Inc. 4809 Paraca Inc. 3654 HITO-Communications,Inc. 5204 ISHIZUKA GLASS CO.,LTD. 3666 TECNOS JAPAN INCORPORATED 5998 Advanex Inc. 3678 MEDIA DO Co.,Ltd. 6203 Howa Machinery,Ltd. 3688 VOYAGE GROUP,INC. 6319 SNT CORPORATION 3694 OPTiM CORPORATION 6362 Ishii Iron Works Co.,Ltd. 3724 VeriServe Corporation 6373 DAIDO KOGYO CO.,LTD. 3765 GungHo Online Entertainment,Inc. -

Proposal of a Data Processing Guideline for Realizing Automatic Measurement Process with General Geometrical Tolerances and Contactless Laser Scanning

Proposal of a data processing guideline for realizing automatic measurement process with general geometrical tolerances and contactless laser scanning 2018/4/4 Atsuto Soma Hiromasa Suzuki Toshiaki Takahashi Copyright (c)2014, Japan Electronics and Information Technology Industries Association, All rights reserved. 1 Contents • Introduction of the Project • Problem Statements • Proposed Solution – Proposal of New General Geometric Tolerance (GGT) – Data Processing Guidelines for point cloud • Next Steps Copyright (c)2014, Japan Electronics and Information Technology Industries Association, All rights reserved. 2 Contents • Introduction of the Project • Problem Statements • Proposed Solution – Proposal of New General Geometric Tolerance (GGT) – Data Processing Guidelines for Point Cloud • Next Steps Copyright (c)2014, Japan Electronics and Information Technology Industries Association, All rights reserved. 3 Introduction of JEITA What is JEITA? The objective of the Japan Electronics and Information Technology Industries Association (JEITA) is to promote healthy manufacturing, international trade and consumption of electronics products and components in order to contribute to the overall development of the electronics and information technology (IT) industries, and thereby to promote further Japan's economic development and cultural prosperity. JEITA’s Policy and Strategy Board > Number of full members: 279> Number of associate members: 117(as of May 13, 2014) - Director companies and chair/subchair companies - Policy director companies (alphabetical) Fujitsu Limited (chairman Masami Yamamoto) Asahi Glass Co., Ltd. Nichicon Corporation Sharp Corporation Azbil Corporation IBM Japan, Ltd. Hitachi, Ltd. Advantest Corporation Nippon Chemi-Con Corporation Panasonic Corporation Ikegami Tsushinki Co., Ltd. Japan Aviation Electronics Industry, Ltd. SMK Corporation Mitsubishi Electric Corporation Nihon Kohden Corporation Omron Corporation NEC Corporation JRC Nihon Musen Kyocera Corporation Sony Corporation Hitachi Metals, Ltd KOA Corporation Fuji Xerox Co., Ltd. -

JASIS 2019 Exhibitors

JASIS 2019 Exhibitors Elemental Scientic, Inc. A Elementar Japan K.K. a priori Inc. ELGA LabWater A&D Company, Limited ELIONIX INC. ACTAC.CO.,LTD Emerging Technologies Corporation. Acumentech Co., Ltd. entex inc. AD Science Inc. Eppendorf Co., Ltd. Advanced Energy Japan K.K. ERECTA International Corporation Advantec Toyo Kaisha, Ltd. ESPEC CORP. ADVANTEST CORPORATION ESPEC MIC CORP. Agilent Technologies Japan,Ltd. ETRI AINEX CO., LTD. Excimer,inc AIRIX Corp. Airtech Corporation AIVS Corporation F Alpha M.O.S. Japan K.K. Filgen, Inc. AMETEK Co, Ltd FLON CHEMICAL INC. AMR, Inc. FLON INDUSTRY CO., LTD. analytica-Messe Muenchen ForDx, Inc. Analytik Jena Japan Co., Ltd. Forum for Innovative Regenerative Medicine(FIRM) ANRITSU METER CO., LTD. FUJIKIN Incorporated Anton Paar Japan K.K. Fujitsu Limited Aomori Prefecture Quantum Science Center FUKUSHIMA INDUSTRIES CORP. APRO Science Institute, Inc. FUSO Co., Ltd. ARAM CORPORATION FUTA-Q,Ltd. AS ONE CORPORATION ASAHI KOHSAN Co.,Ltd Asahi Lab Commerce, Inc. G ASAHI LIFE SCIENCE CO.,LTD GASTEC CORPORATION ASAHI RUBBER INC. GC INSTRUMENTS ASAHI TECHNEION CO., LTD. GE Healthcare Japan Corporation ASCH JAPAN CO.,LTD GERSTEL K.K. ASI-AURORA GL Sciences Inc. ASICON Tokyo Ltd. Glass Expansion Pty. Ltd. Association for structure characterization Global Facility Center,HOKKAIDO UNIVERSITY ASTECH CORPORATION GTR TEC CORPORATION ATAGO CO., LTD. GVS Japan K.K. B H BAS Inc. hagataya.co.ltd BD Consulting L.L.C. Hakuto Co., Ltd. BeatSensing co.,ltd. HAMAMATSU PHOTONICS K.K. Beckman Coulter K.K. Hamilton Company Japan K.K. BEIJING LINGGONG TECHNOLOGY CO.,LTD Hanaichi UltraStructure Research Institute BETHL Co.,Ltd. -

Matsushige, Kazumi Citation IEEE Nanotechnology Magazine (2011)

Title New Research from an Old Capital Author(s) Matsushige, Kazumi Citation IEEE Nanotechnology Magazine (2011), 5(4): 10-14 Issue Date 2011-12 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/152099 c 2011 IEEE. Personal use of this material is permitted. Permission from IEEE must be obtained for all other uses, in any current or future media, including reprinting/republishing this material for advertising or promotional purposes, creating Right new collective works, for resale or redistribution to servers or lists, or reuse of any copyrighted component of this work in other works.; この論文は出版社版でありません。引用の際 には出版社版をご確認ご利用ください。; This is not the published version. Please cite only the published version. Type Journal Article Textversion author Kyoto University Collaborative Promotion of Nanotechnology Researches in Kyoto Area The technology, which can control materials and processes at the nano-scale precision, ”nanotechnology”, has been utilized for a long time in Kyoto, an old capital of Japan. Kyoto is well known not only as a traditional and cultural town but also as one of the most innovative towns in Japan, and has produced many world-wide technology-based start-up (venture) companies, such as Kyocera, Nintendo, Omron, Murata MFG, Rohm, Horiba MFG, Nichicon and more. In these two features of tradition and innovation, there exists potentially a close correlation. Loads or emperor in the capital had gathered the highest level of technologies at their times and created various kinds of artistic works and buildings. Namely, the concentration of high-technology as well as the creation of new technologies are essential to built new industry as well as to keep the activity of the principal towns. -

Kyoto and Keihanna

Knowledge Clusters:TheSecondStage(Active) Knowledge Clusters:TheSecondStage(Active)K n o (Fiscal Year 2008-2012) w Cluster Headquarters Participating Research Organizations (Bold: Core Research Organization) l e ○President……………Masao Horiba (Supreme Counsel of Horiba, Ltd.; Chairman at Innovation Initiative Network Japan) Industry…ALGAN K.K., Ibiden Co., Ltd., Ibidenjushi Co. Ltd., Oike & Co., Ltd., d ○Project Director………Tatsuro Ichihara (Former Director and Executive Vice President of Omron Corporation; Okuno Chemical Industries, Co.,Ltd., Omron Corporation, g e Life Sciences IT Environment Nanotech/Materials Kyoto Environmental Nanotechnology Cluster Former Executive President of Kyoto Sisaku Corporation ) Omron Healthcare Co., Ltd., The Kansai Electric Power Co, Inc., C Kyo-chro Co., Ltd., Kyoto Electronics Manufacturing Co., Ltd., l ○Chief Scientist………Sei-ichi Nishimoto (Professor, Graduate School of Engineering, Kyoto University) u Kyoto Nano Chemical Co., Ltd., KYORIN Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., s ○Deputy Project Director……Junichi Tanaka (Deputy General Manager of Commerce, Industry, Labor and Tourism t Sakigake-Semiconductor Co., Ltd., Samco Inc., Shimadzu Corporation, e Department, Kyoto Prefecture) r JOHNAN Corporation, Shinko MechatroTech Co., Ltd., s : ○Deputy Project Director……Hiroshi Egawa (Chief at the Industry Promotion Section, Industry and Tourism Bureau, City of Kyoto) Suzuki Sangyo Co., Ltd., Sumitomo Electric Industries, Ltd., T ○Deputy Chief Scientist……Kazuyuki Hirao (Professor, Graduate School of Engineering, Kyoto -

Stago 2011 Ed 2.Pub

1 Stago Newsletter Volume 2, Issue 2 August 2011 2 ISTH Internaonal Society on ISTH Kyoto Japan Thrombosis and Haemostasis INSIDE THIS ISSUE: The 23rd International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis met at Kyoto, Japan from July 23 -28, 2011. ISTH XXIII Kyoto 2 Kyoto ( 京都, Ky ōto, "Capital city") is a city in the central part of the is- Data backup options 3 land of Honsh ū, Japan. It has a population close to 1.5 million. Formerly the Training Needs? 3 imperial capital of Japan, it is now the capital of Kyoto Prefecture, as well as a major part of the architecture intact, it is one those bringing such items The CAT 4 Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto of the best preserved cities would be inclined to metropolitan area. in Japan. answer this truthfully? Luckily I had left my cobra Kyoto is renowned for its Kyoto has a humid sub- at home! Dabigatran 5 tropical climate. The abundance of delicious temperature was 32° Japanese foods and The ISTH meeting was “full Celsius (overnight 24°C) cuisine. The special on” with 8am starts for the Technical Information 6 and very humid. circumstances of Kyoto as sub committee meetings on a city away from the sea Saturday and Sunday Although ravaged by and home to many followed by the congress wars, fires, and Buddhist temples resulted program running Monday- Dates to Remember 7 earthquakes during its in the development of a Thursday. There were eleven centuries as the variety of vegetables approximately 500 posters imperial capital, Kyoto peculiar to the Kyoto area . -

CDP Japan Water Security Report 2019

CDP Japan Water Security Report 2019 On behalf of 525 institutional investors with assets of USD 96 trillion CDP Japan Water Security Report 2019 | 2020 March Report writer Contents CDP Foreword 3 Report Writer Foreword 4 Water Security A List 2019 6 Scoring 7 Stories of Change 8 - Kao Corporation - Japan Tobacco Inc. Executive Summary 12 Response to CDP’s Water Security Questionnaire 14 Appendix 22 - CDP Water Security 2019 Japanese companies Please note that the names of companies in the text do not indicate their corporate status. Important Notice The contents of this report may be used by anyone providing acknowledgment is given to CDP. This does not represent a license to repackage or resell any of the data reported to CDP or the contributing authors and presented in this report. If you intend to repackage or resell any of the contents of this report, you need to obtain express permission from CDP before doing so. CDP has prepared the data and analysis in this report based on responses to the CDP 2019 information request. No representation or warranty (express or implied) is given by CDP as to the accuracy or completeness of the information and opinions contained in this report. You should not act upon the information contained in this publication without obtaining specific professional advice. To the extent permitted by law, CDP does not accept or assume any liability, responsibility or duty of care for any consequences of you or anyone else acting, or refraining to act, in reliance on the information contained in this report or for any decision based on it. -

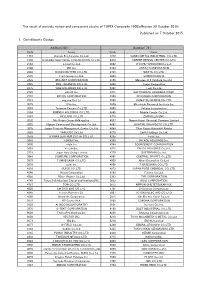

Published on 7 October 2015 1. Constituents Change the Result Of

The result of periodic review and component stocks of TOPIX Composite 1500(effective 30 October 2015) Published on 7 October 2015 1. Constituents Change Addition( 80 ) Deletion( 72 ) Code Issue Code Issue 1712 Daiseki Eco.Solution Co.,Ltd. 1972 SANKO METAL INDUSTRIAL CO.,LTD. 1930 HOKURIKU ELECTRICAL CONSTRUCTION CO.,LTD. 2410 CAREER DESIGN CENTER CO.,LTD. 2183 Linical Co.,Ltd. 2692 ITOCHU-SHOKUHIN Co.,Ltd. 2198 IKK Inc. 2733 ARATA CORPORATION 2266 ROKKO BUTTER CO.,LTD. 2735 WATTS CO.,LTD. 2372 I'rom Group Co.,Ltd. 3004 SHINYEI KAISHA 2428 WELLNET CORPORATION 3159 Maruzen CHI Holdings Co.,Ltd. 2445 SRG TAKAMIYA CO.,LTD. 3204 Toabo Corporation 2475 WDB HOLDINGS CO.,LTD. 3361 Toell Co.,Ltd. 2729 JALUX Inc. 3371 SOFTCREATE HOLDINGS CORP. 2767 FIELDS CORPORATION 3396 FELISSIMO CORPORATION 2931 euglena Co.,Ltd. 3580 KOMATSU SEIREN CO.,LTD. 3079 DVx Inc. 3636 Mitsubishi Research Institute,Inc. 3093 Treasure Factory Co.,LTD. 3639 Voltage Incorporation 3194 KIRINDO HOLDINGS CO.,LTD. 3669 Mobile Create Co.,Ltd. 3197 SKYLARK CO.,LTD 3770 ZAPPALLAS,INC. 3232 Mie Kotsu Group Holdings,Inc. 4007 Nippon Kasei Chemical Company Limited 3252 Nippon Commercial Development Co.,Ltd. 4097 KOATSU GAS KOGYO CO.,LTD. 3276 Japan Property Management Center Co.,Ltd. 4098 Titan Kogyo Kabushiki Kaisha 3385 YAKUODO.Co.,Ltd. 4275 Carlit Holdings Co.,Ltd. 3553 KYOWA LEATHER CLOTH CO.,LTD. 4295 Faith, Inc. 3649 FINDEX Inc. 4326 INTAGE HOLDINGS Inc. 3660 istyle Inc. 4344 SOURCENEXT CORPORATION 3681 V-cube,Inc. 4671 FALCO HOLDINGS Co.,Ltd. 3751 Japan Asia Group Limited 4779 SOFTBRAIN Co.,Ltd. 3844 COMTURE CORPORATION 4801 CENTRAL SPORTS Co.,LTD. -

Ief-I Q3 2020

Units Cost Market Value INTERNATIONAL EQUITY FUND-I International Equities 96.98% International Common Stocks AUSTRALIA ABACUS PROPERTY GROUP 1,012 2,330 2,115 ACCENT GROUP LTD 3,078 2,769 3,636 ADBRI LTD 222,373 489,412 455,535 AFTERPAY LTD 18,738 959,482 1,095,892 AGL ENERGY LTD 3,706 49,589 36,243 ALTIUM LTD 8,294 143,981 216,118 ALUMINA LTD 4,292 6,887 4,283 AMP LTD 15,427 26,616 14,529 ANSELL LTD 484 8,876 12,950 APA GROUP 14,634 114,162 108,585 APPEN LTD 11,282 194,407 276,316 AUB GROUP LTD 224 2,028 2,677 AUSNET SERVICES 9,482 10,386 12,844 AUSTRALIA & NEW ZEALAND BANKIN 19,794 340,672 245,226 AUSTRALIAN PHARMACEUTICAL INDU 4,466 3,770 3,377 BANK OF QUEENSLAND LTD 1,943 13,268 8,008 BEACH ENERGY LTD 3,992 4,280 3,824 BEGA CHEESE LTD 740 2,588 2,684 BENDIGO & ADELAIDE BANK LTD 2,573 19,560 11,180 BHP GROUP LTD 16,897 429,820 435,111 BHP GROUP PLC 83,670 1,755,966 1,787,133 BLUESCOPE STEEL LTD 9,170 73,684 83,770 BORAL LTD 6,095 21,195 19,989 BRAMBLES LTD 135,706 987,557 1,022,317 BRICKWORKS LTD 256 2,997 3,571 BWP TRUST 2,510 6,241 7,282 CENTURIA INDUSTRIAL REIT 1,754 3,538 3,919 CENTURIA OFFICE REIT 154,762 199,550 226,593 CHALLENGER LTD 2,442 13,473 6,728 CHAMPION IRON LTD 1,118 2,075 2,350 CHARTER HALL LONG WALE REIT 2,392 8,444 8,621 CHARTER HALL RETAIL REIT 174,503 464,770 421,358 CHARTER HALL SOCIAL INFRASTRUC 1,209 2,007 2,458 CIMIC GROUP LTD 4,894 73,980 65,249 COCA-COLA AMATIL LTD 2,108 12,258 14,383 COCHLEAR LTD 1,177 155,370 167,412 COMMONWEALTH BANK OF AUSTRALIA 12,637 659,871 577,971 CORONADO GLOBAL RESOURCES INC 1,327