Dr Andy Williams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gill Morgan, Is Dealing with Whitehall Arrogance

plus… Jeff Jones Labour’s leadership election Nicola Porter Journalism must fight back Barry Morgan Religion and politics Dafydd Wigley Options for the referendum Andrew Shearer Garlic’s secret weapon Gill David Culshaw Decline of the honeybee Gordon James Coal in a warm climate Morgan Katija Dew Beating the crunch Gear change for our civil service Andrew Davies The Kafka Brigade Peter Finch Capturing the soul www.iwa.org.uk Winter 2009 No. 39 | £5 clickonwales ! Coming soon, our new website www. iwa.or g.u k, containing much more up-to-date news and information and with a freshly designed new look. Featuring clickonwales – the IWA’s new online service providing news and analysis about current affairs as it affects our small country. Expert contributors from across the political spectrum will be commissioned daily to provide insights into the unfolding drama of the new 21 st Century Wales – whether it be Labour’s leadership election, constitutional change, the climate change debate, arguments about education, or the ongoing problems, successes and shortcomings of the Welsh economy. There will be more scope, too, for interactive debate, and a special section for IWA members. Plus: Information about the IWA’s branches, events, and publications. This will be the must see and must use Welsh website. clickonwales and see where it takes you. clickonwales and see how far you go. The Institute of Welsh Affairs gratefully acknowledges core funding from the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust , the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation and the Waterloo Foundation . The following organisations are corporate members: Private Sector • Principality Building Society • The Electoral Commission Certified Accountants • Abaca Ltd • Royal Hotel Cardiff • Embassy of Ireland • Autism Cymru • Beaufort Research • Royal Mail Group Wales • Fforwm • Cartrefi Cymunedol / • Biffa Waste Services Ltd • RWE NPower Renewables • The Forestry Commission Community Housing Cymru • British Gas • S. -

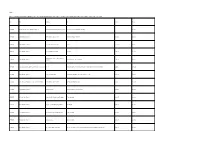

WELSH GOVERNMENT - BERNARD GALTON, DIRECTOR GENERAL, PEOPLE, PLACES & CORPORATE SERVICES Business Expenses: April – June 2011

WELSH GOVERNMENT - BERNARD GALTON, DIRECTOR GENERAL, PEOPLE, PLACES & CORPORATE SERVICES Business Expenses: April – June 2011 DATES DESTINATION PURPOSE TRAVEL OTHER (Including Total Cost Hospitality Given) £ Air Rail Taxi / Hire Car/Own Accommodation / car Meals 11/5/11- London Attend various meetings £126.00 £319.98 £445.98 13/5/11 at Cabinet Office 24/5/11- London Attend various meetings £63.00 £169.00 £232.00 25/5/11 26/5/11 London Attend HR Management £114.10 £114.10 Team at Cabinet Office 21/6/11 London Attend HR Management £164.50 £164.50 Team 27/6/11 Lampeter Open Summer School £81.00 £81.00 TOTAL £1,037.58 Hospitality DATE INVITEE/COMPANY EVENT/GIFT COST 24/5/11 Odgers Berndtson Annual HR Directors’ Dinner £40 TOTAL £40 WELSH GOVERNMENT – Clive Bates, Director General, Sustainable Futures Business Expenses: April – June 2011 DATES DESTINATION PURPOSE TRAVEL OTHER (Including Total Hospitality Given) Cost £ Air Rail Taxi / Car Accommodation / Meals 13.4.11 Gwesty Cymru Hotel, Overnight stay at hotel £104.45 £104.45 Aberystwyth for staff visit on 14 April 13- Travel from Home to Travel expenses in own £99.45 £99.45 14.4.11 Hotel Gwesty for car for visit to overnight stay, then Aberystwyth onto Aberystwyth offices and onto home address. 26.4.11 Return train travel from Visit with Newport £4.20 £4.20 Cardiff to Newport Unlimited 12.5.11 Train ticket between To attend Top 200 event £28.50 + £60.50 Cardiff and London £32.00 19.5.11 Train ticket Cardiff – To attend Climate £4.00 £4.00 Barry Docks return Change & Energy- Member Development & Training for Vale of Glamorgan Council 27.5.11 Return train travel to to attend CBI dinner £7.30 £7.30 Swansea on 7 June (speaking at event) 27.5.11 Return train travel to to attend Climate £66.00 + £88.00 for London Change Forum Private £22.00 travel Dinner on 8.6.11 27.6.11 Wolfscastle Country Intended Overnight stay £78.00 £78.00 Hotel, to attend CCW Annual Wolfscastle, meeting & Dinner, Haverfordwest however cancelled on Pembrokeshire. -

Jane Hutt: Businesses That Have Received Welsh Government Grants During 2011/12

Jane Hutt: Businesses that have received Welsh Government grants during 2011/12 1 STOP FINANCIAL SERVICES 100 PERCENT EFFECTIVE TRAINING 1MTB1 1ST CHOICE TRANSPORT LTD 2 WOODS 30 MINUTE WORKOUT LTD 3D HAIR AND BEAUTY LTD 4A GREENHOUSE COM LTD 4MAT TRAINING 4WARD DEVELOPMENT LTD 5 STAR AUTOS 5C SERVICES LTD 75 POINT 3 LTD A AND R ELECTRICAL WALES LTD A JEFFERY BUILDING CONTRACTOR A & B AIR SYSTEMS LTD A & N MEDIA FINANCE SERVICES LTD A A ELECTRICAL A A INTERNATIONAL LTD A AND E G JONES A AND E THERAPY A AND G SERVICES A AND P VEHICLE SERVICES A AND S MOTOR REPAIRS A AND T JONES A B CARDINAL PACKAGING LTD A BRADLEY & SONS A CUSHLEY HEATING SERVICES A CUT ABOVE A FOULKES & PARTNERS A GIDDINGS A H PLANT HIRE LTD A HARRIES BUILDING SERVICES LTD A HIER PLUMBING AND HEATING A I SUMNER A J ACCESS PLATFORMS LTD A J RENTALS LIMITED A J WALTERS AVIATION LTD A M EVANS A M GWYNNE A MCLAY AND COMPANY LIMITED A P HUGHES LANDSCAPING A P PATEL A PARRY CONSTRUCTION CO LTD A PLUS TRAINING & BUSINES SERVICES A R ELECTRICAL TRAINING CENTRE A R GIBSON PAINTING AND DEC SERVS A R T RHYMNEY LTD A S DISTRIBUTION SERVICES LTD A THOMAS A W JONES BUILDING CONTRACTORS A W RENEWABLES LTD A WILLIAMS A1 CARE SERVICES A1 CEILINGS A1 SAFE & SECURE A19 SKILLS A40 GARAGE A4E LTD AA & MG WOZENCRAFT AAA TRAINING CO LTD AABSOLUTELY LUSH HAIR STUDIO AB INTERNET LTD ABB LTD ABER GLAZIERS LTD ABERAVON ICC ABERDARE FORD ABERGAVENNY FINE FOODS LTD ABINGDON FLOORING LTD ABLE LIFTING GEAR SWANSEA LTD ABLE OFFICE FURNITURE LTD ABLEWORLD UK LTD ABM CATERING FOR LEISURE LTD ABOUT TRAINING -

Equality Issues in Wales: a Research Review

Research report: 11 Equality issues in Wales: a research review Victoria Winckler (editor) The Bevan Foundation Equality issues in Wales: a research review Victoria Winckler (editor) The Bevan Foundation © Equality and Human Rights Commission 2009 First published Spring 2009 ISBN 978 1 84206 089 6 Equality and Human Rights Commission Research Report Series The Equality and Human Rights Commission Research Report Series publishes research carried out for the Commission by commissioned researchers. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Commission. The Commission is publishing the report as a contribution to discussion and debate. Please contact the Research Team for further information about other Equality and Human Rights Commission’s research reports, or visit our website: Research Team Equality and Human Rights Commission Arndale House Arndale Centre Manchester M4 3AQ Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0161 829 8500 Website: www.equalityhumanrights.com You can download a copy of this report as a PDF from our website: www.equalityhumanrights.com/researchreports If you require this publication in an alternative format, please contact the Communications Team to discuss your needs at: [email protected] CONTENTS Page CHAPTER AUTHORS i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY iii 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 This Report 1 1.2 Demography of Wales 2 1.3 Governance of Wales 12 1.4 Devolution and Equality 13 1.5 Conclusion 17 2. POVERTY AND SOCIAL EXCLUSION 18 2.1 Policy Context 18 2.2 Household Income and Poverty 19 2.3 Benefits and Pensions 28 2.4 Savings, Credit and Debt, and Financial Exclusion 31 2.5 Water and Fuel Poverty 35 2.6 Digital Inclusion 37 2.7 Culture, Leisure and Sport 38 2.8 Access to Advice, Support and Justice 42 2.9 Transport 44 2.10 Conclusions and Research Gaps 51 3. -

SKILLSCYMRU 2015 Benefits

The careers and skills events for Wales VENUE CYMRU, LLANDUDNO 7-8 October 2015 MOTORPOINT ARENA, CARDIFF 21-22 October 2015 TARGET AUDIENCE • An audience of 8,000 pupils in South Wales and 3,000 in North. • Students from schools and colleges across Wales. • In addition key influencers, parents and teachers. BENEFITS FOR EXHIBITORS • Actively recruit young people and adults • Promote long-term careers • Network and make valuable contacts in schools, colleges, universities, with other employers and other professional organisations • Develop links with careers professionals who advise and influence students • Increase brand awareness • Launch new services BENEFITS FOR VISITORS • Discover and find more information on a huge range of career areas and job opportunities in one place, at one time • Get help from careers advisers and professionals, other information, advice and guidance • Try out new skills including those that the visitor may not have even thought about • Ask employers, training providers, colleges, questions face to face • Discover actual jobs on offer • Find out about current initiatives • Have a good day out! COSTS FOR STAND SPACE • Cardiff - £285+VAT per m2 • Llandudno - £210+VAT per m2 EXAMPLES OF COSTS: COST STAND SIZE CARDIFF LLANDUDNO 2m x 2m £1140+VAT £840+VAT 3m x 2m £1710+VAT £1260+VAT 4m x 3m £3420+VAT £2520+VAT 5m x 3m £4275+VAT £3150+VAT 4m x 4m £4560+VAT £3360+VAT 6m x 8m £13680+VAT £10080+VAT Discounted rates may be available for some sectors Included in the stand cost: • Shell scheme stand • Name board on each open side of the stand • Stand lighting – two spotlights • Stand carpet Cost of 2 chairs, a table and electricity point is £175+VAT. -

English Is a Welsh Language

ENGLISH IS A WELSH LANGUAGE Television’s crisis in Wales Edited by Geraint Talfan Davies Published in Wales by the Institute of Welsh Affairs. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means without the prior permission of the publishers. © Institute of Welsh Affairs, 2009 ISBN: 978 1 904773 42 9 English is a Welsh language Television’s crisis in Wales Edited by Geraint Talfan Davies The Institute of Welsh Affairs exists to promote quality research and informed debate affecting the cultural, social, political and economic well-being of Wales. IWA is an independent organisation owing no allegiance to any political or economic interest group. Our only interest is in seeing Wales flourish as a country in which to work and live. We are funded by a range of organisations and individuals. For more information about the Institute, its publications, and how to join, either as an individual or corporate supporter, contact: IWA - Institute of Welsh Affairs 4 Cathedral Road Cardiff CF11 9LJ tel 029 2066 0820 fax 029 2023 3741 email [email protected] web www.iwa.org.uk Contents 1 Preface 4 1/ English is a Welsh language, Geraint Talfan Davies 22 2/ Inventing Wales, Patrick Hannan 30 3/ The long goodbye, Kevin Williams 36 4/ Normal service, Dai Smith 44 5/ Small screen, big screen, Peter Edwards 50 6/ The drama of belonging, Catrin Clarke 54 7/ Convergent realities, John Geraint 62 8/ Standing up among the cogwheels, Colin Thomas 68 9/ Once upon a time, Trevor -

Prices Exclusive of VAT Monthly Unique Visitors

2016 MEDIA PACK All prices exclusive of VAT monthly unique visitors reaches over 1 in 2 PEOPLE IN WALES (SOURCE: ETELMAR JICREG NOV 2016, ABC JUNE 2016, COMSCORE) 3.5m WHATEVER YOUR BUSINESS OBJECTIVE OR TARGET AUDIENCE, WE'VE GOT THE SOLUTION 3.5m DIGITAL SOLUTIONS OUR AUDIENCE THE MOST POPULAR REGIONAL WEBSITE FOR WELSH NEWS, SPORT, LIFESTYLE AND ENTERTAINMENT INFORMATION IN THE NATION 24,275,825 3,595,667 30,000 MONTHLY PAGEVIEWS MONTHLY UNIQUE VISITORS MONTHLY APP UNIQUE BROWSERS WalesOnline WalesOnline WalesRugby CardiffOnline WALESONLINE 324K 143K 39K 40K REACHES 49% OF ADULTS IN WALES Likes Followers Followers Followers Source: Comscore unique visitors monthly average Jan-June 2016, App unique browsers ABC June 2016, Penetration in Wales JICREG Nov 2016. Social Media figures as at Nov2016. OUR AUDIENCE BREAKDOWN DESKTOP MOBILE WalesOnline APP 10,441,761 PAGEVIEWS 13,803,491 PAGEVIEWS 4,991,420 MONTHLY PAGE VIEWS 30,000 MONTHLY UNIQUE BROWSERS 1,765,772 UNIQUE BROWSERS 2,791,049 UNIQUE BROWSERS 777,167 UNIQUE VISITORS 2,818,500 UNIQUE VISITORS (This figure is de-duplicated by ComScore) GENDER AGE DEMOGRAPHIC 15-34 35-54 55+ ABC1 C2DE 48% 52% 26% 34% 40% 37% 48% Source: Market share & Demographics JICREG 01/11/2015 Base: Wales. ABC June 2016 DIGITAL PACKAGES STANDARD £10CPM (CPM = COST PER THOUSAND) ENHANCED £15CPM ENGAGE OUR AUDIENCE HOW YOU WANT, WHEN YOU WANT AND WITH MORE CREATIVITY LEADERBOARD MPU BILLBOARD MMA/APP BANNER MOBILE MPU SUPER MPU MOBILE OVERLAY TARGET A SEGMENT OF OUR AUDIENCE - Pick your ad format - Choose a site -

Broadcasting in Wales

House of Commons Welsh Affairs Committee Broadcasting in Wales First Report of Session 2016–17 HC 14 House of Commons Welsh Affairs Committee Broadcasting in Wales First Report of Session 2016–17 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 13 June 2016 HC 14 Published on 16 June 2016 by authority of the House of Commons Welsh Affairs Committee The Welsh Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Office of the Secretary of State for Wales (including relations with the National assembly for Wales.) Current membership David T.C. Davies MP (Conservative, Monmouth) (Chair) Byron Davies MP (Conservative, Gower) Chris Davies MP (Labour, Brecon and Radnorshire) Glyn Davies MP (Conservative, Montgomeryshire) Dr James Davies MP (Conservative, Vale of Clwyd) Carolyn Harris MP (Labour, Swansea East) Gerald Jones MP (Labour, Merthyr Tydfil and Rhymney) Stephen Kinnock MP (Labour, Abervaon) Liz Saville Roberts MP (Plaid Cymru, Dwyfor Meirionnydd) Craig Williams MP (Conservative, Cardiff North) Mr Mark Williams MP (Liberal Democrat, Ceredigion) The following were also members of the Committee during this inquiry Christina Rees MP (Labour, Neath) and Antoinette Sandbach MP (Conservative, Eddisbury) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www. parliament.uk. Publication Committee reports are published on the Committee’s website at www.parliament.uk/welshcom and in print by Order of the House. -

7 Shocking Local News Industry Trends Which Should Terrify You

Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru / National Assembly for Wales Pwyllgor Diwylliant, y Gymraeg a Chyfathrebu / The Culture, Welsh Language and Communications Committee Newyddiaduraeth Newyddion yng Nghymru / News Journalism in Wales CWLC(5) NJW10 Ymateb gan Dr. Andy Williams, Prifysgol Caerdydd / Evidence from Dr. Andy Williams, Cardiff University 7 shocking local news industry trends which should terrify you. The withdrawal of established journalism from Welsh communities and its effects on public interest reporting. In the first of two essays about local news in Wales, I draw on Welsh, UK, and international research, published company accounts, trade press coverage, and first-hand testimony about changes to the economics, journalistic practices, and editorial priorities of established local media. With specific reference to the case study of Media Wales (and its parent company Trinity Mirror) I provide an evidence-based and critical analysis which charts both the steady withdrawal of established local journalism from Welsh communities and the effects of this retreat on the provision of accurate and independent local news in the public interest. A second essay, also submitted as evidence to this committee, explores recent research about the civic and democratic value of a new generation of (mainly online) community news producers. Local newspapers are in serious (and possibly terminal) decline In 1985 Franklin found 1,687 local newspapers in the UK (including Sunday and free titles); by 2005 this had fallen by almost a quarter to 1,286 (Franklin 2006b). By 2015 the figure stood at 1,100, a 35% drop over 30 years, with a quarter of those lost being paid-for newspapers (Ramsay and Moore 2016). -

Note Where Company Not Shown Separately, There

Note Where company not shown separately, there are identified against the 'item' Where a value is not shown, this is due to the nature of the item e.g. 'event' Date Post Company Item Value Status 27/01/2010 Director General Finance & Corproate Services Cardiff Council & Welsh Assembly Government Invitation to attend Holocaust Memorial Day declined 08/04/2010 First Legislative Counsel Welsh Assembly Government Retirement Seminar - Reception Below 20 accepted 12/04/2010 First Legislative Counsel Clwb Cinio Cymraeg Caerdydd Dinner Below 20 accepted 14/04/2010 First Legislative Counsel Clwb Cymrodorion Caerdydd Reception Below 20 accepted Sir Christopher Jenkins - ex Parliamentary 19/04/2010 First Legislative Counsel Lunch at the Bear Hotel, Crickhowell Below 20 accepted Counsel 21/04/2010 Acting Deputy Director, Lifelong Learners & Providers Division CIPFA At Cardiff castle to recognise 125 years of CIPFA and opening of new office in Cardiff £50.00 Accepted 29/04/2010 First Legislative Counsel University of Glamorgan Buffet lunch - followed by Chair of the afternoon session Below 20 accepted 07/05/2010 Deputy Director, Engagement & Student Finance Division Student Finance Officers Wales Lunch provided during meeting £10.00 Accepted 13/05/2010 First Legislative Counsel Swiss Ambassador Reception at Mansion House, Cardiff Below 20 accepted 14/05/2010 First Legislative Counsel Ysgol y Gyfraith, Coleg Prifysgol Caerdydd Cinio canol dydd Below 20 accepted 20/05/2010 First Legislative Counsel Pwyllgor Cyfreithiol Eglwys yng Nghymru Te a bisgedi -

7 April 2020 Helen Mary Jones AM National Assembly for Wales Cardiff Bay CF99 1NA Dear Helen, I Hope You're Keeping Safe and W

7 April 2020 Helen Mary Jones AM National Assembly for Wales Cardiff Bay CF99 1NA Dear Helen , I hope you’re keeping safe and well in these extraordinary times. I wanted to write to brief and reassure you about the cost reduction measures you may have seen announced yesterday by Reach plc, and their impact on our operations here at Media Wales. Across our group, which as I’m sure you know publishes the Mirror, the Express, the Daily Record and regional titles including the Manchester Evening News and Liverpool Echo alongside our Welsh titles, around 20% of the workforce was furloughed yesterday. In addition, all staff were asked to take a pay cut of 10%, with the board and senior team taking 20%. Those on furlough will have their pay topped up by 10% so they are not financially disadvantaged compared to those colleagues who have been able to continue in their roles. Asking hard-working colleagues to step back from the crucial work of keeping the public informed about the coronavirus pandemic in their areas, as well as producing other content allowing for much- needed diversion from the relentlessness of the bleak news agenda, made me desperately sad. At Media Wales, we pride ourselves on the products and audiences that we’ve built. Asking people to leave that work behind, albeit temporarily, was a difficult task for us all. The last few weeks have demonstrated the crucial role regional and local publishers like us play in keeping the public informed about the matters that affect their lives. With many unable to get to shops to buy newspapers, our online traffic - driven largely by our live updates and informational content about the pandemic - has increased by around 70% since the outbreak began. -

Big Pitch Event Programme

Acknowledgements Big Pitch Challenge Chris Mason, Techniquest Sponsors: Enterprising Merthyr Equinox Communications Heads of the Valleys Innovation Programme Supported by: Welsh Assembly Government Project Team: Julian Newberry, Coleg Gwent Lynne Parfitt, Coleg Morgannwg Christine Bissex, Merthyr Tydfil College Lesley Cottrell, The College Ystrad Mynach Elin McCallum, Welsh Assembly Government th Sharon Phillips, Merthyr Tydfil CBC Thursday 25 November 2010 Wendy Locke, Virtual Assistance Phil Burkhard, HOVIP 5pm to 9:30pm Judges: Techniquest Steve Evans, Chairman, Rhymney Brewery Nick Hewer Chris Kelsey, Business in Wales Editor, Media Wales Eryl Jones, MD, Equinox Communications Businesses: Aberfanturning (gift pens for judges), Alison Richards Ceramics (trophy), Anytime Films, CIOTEK Ltd. (training), Helen Murdoch Marketing Ltd. (training) Penderyn Distillery (site visit), Rhymney Brewery (site visit) Rose-Innes Designs (site visit) Welcome Programme We live in challenging times when it is vital to give our young people the skills and opportunities to flourish. What better way to achieve 5:00pm Arrival / Registration this than by igniting their passion and ability to learn in the furnace of the real world? 5:50pm Welcome Address The seeds for tonight were sown a year ago when Merthyr Tydfil College students were invited to present their recommendations on 6:00pm Student Presentations how to market the Welsh International Climbing Centre. As John O’Shea (Dean of Merthyr Tydfil College and FE Collaboration) said: 8:00pm Buffet / Techniquest Display / “The initiative provided an excellent real life opportunity for Judging learners to develop entrepreneurial skills. The Trustees and Parc Taf Bargoed now have a wealth of ideas.” 8:45pm Awards Ceremony The event also created a positive press which was a stepping stone to attracting a major investor to Wales to run what is now the Rock 9:00pm Q&A Session UK Summit Centre.