Uncovering the Truth in Foreign Aviation Disasters and Evaluating the Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uncontrolled Descent and Collision with Terrain, United Airlines 585

PB2001-910401 NTSB/AAR-01/01 DCA91MA023 NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY BOARD WASHINGTON, D.C. 20594 AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT REPORT Uncontrolled Descent and Collision With Terrain United Airlines Flight 585 Boeing 737-200, N999UA 4 Miles South of Colorado Springs Municipal Airport Colorado Springs, Colorado March 3, 1991 5498C Aircraft Accident Report Uncontrolled Descent and Collision With Terrain United Airlines Flight 585 Boeing 737-200, N999UA 4 Miles South of Colorado Springs Municipal Airport Colorado Springs, Colorado March 3, 1991 RAN S P T O L R A T LURIBUS N P UNUM A E O T I I O T N A N S A D FE R NTSB/AAR-01/01 T Y B OA PB2001-910401 National Transportation Safety Board Notation 5498C 490 L’Enfant Plaza, S.W. Adopted March 27, 2001 Washington, D.C. 20594 National Transportation Safety Board. 2001. Uncontrolled Descent and Collision With Terrain, United Airlines Flight 585, Boeing 737-200, N999UA, 4 Miles South of Colorado Springs Municipal Airport, Colorado, Springs, Colorado, March 3, 1991. Aircraft Accident Report NTSB/AAR-01/01. Washington, DC. Abstract: This amended report explains the accident involving United Airlines flight 585, a Boeing 737-200, which entered an uncontrolled descent and impacted terrain 4 miles south of Colorado Springs Municipal Airport, Colorado Springs, Colorado, on March 3, 1991. Safety issues discussed in the report are the potential meterological hazards to airplanes in the area of Colorado Springs; 737 rudder malfunctions, including rudder reversals; and the design of the main rudder power control unit servo valve. The National Transportation Safety Board is an independent Federal agency dedicated to promoting aviation, railroad, highway, marine, pipeline, and hazardous materials safety. -

National Transportation Safety Board Washington, Dc 20594 Aircraft

PB99-910401 ‘I NTSB/AAR-99/01 DCA94MA076 NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY BOARD WASHINGTON, D.C. 20594 AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT REPORT UNCONTROLLED DESCENT AND COLLISION WITH TERRAIN USAIR FLIGHT 427 BOEING 737-300, N513AU NEAR ALIQUIPPA, PENNSYLVANIA SEPTEMBER 8, 1994 6472A Abstract: This report explains the accident involving USAir flight 427, a Boeing 737-300, which entered an uncontrolled descent and impacted terrain near Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, on September 8, 1994. Safety issues in the report focused on Boeing 737 rudder malfunctions, including rudder reversals; the adequacy of the 737 rudder system design; unusual attitude training for air carrier pilots; and flight data recorder parameters. Safety recommendations concerning these issues were addressed to the Federal Aviation Administration. The National Transportation Safety Board is an independent Federal Agency dedicated to promoting aviation, raiload, highway, marine, pipeline, and hazardous materials safety. Established in 1967, the agency is mandated by Congress through the Independent Safety Board Act of 1974 to investigate transportation accidents, study transportation safety issues, and evaluate the safety effectiveness of government agencies involved in transportation. The Safety Board makes public its actions and decisions through accident reports, safety studies, special investigation reports, safety recommendations, and statistical reviews. Recent publications are available in their entirety at http://www.ntsb.gov/. Other information about available publications may also be obtained from the Web site or by contacting: National Transportation Safety Board Public Inquiries Section, RE-51 490 L’Enfant Plaza, East, S.W. Washington, D.C. 20594 Safety Board publications may be purchased, by individual copy or by subscription, from the National Technical Information Service. -

Parker-100-Year-Journey Rev2.Pdf

Parker Hannifin’s 100-Year Journey COPYRIGHT © 2017 Thomas A. Piraino Jr. and Parker Hannifin Corp. All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording or other digital or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the author, except in the cases of fair use as permitted by U.S. and international copyright laws. For permission requests, please submit in writing to the publisher at the address below: Published by: Smart Business Network 835 Sharon Drive, Suite 200 Westlake, OH 44145 Printed in the United States of America Cover and interior design: Stacy Vickroy Cover layout: April Grasso and Stacy Vickroy Interior layout: April Grasso and RJ Pooch Editor: Dustin S. Klein ISBN: 978-1-945389-95-5 (hardcover) ISBN: 978-1-945389-96-2 (e-book) Library of Congress Control Number: 2017941262 “It is doubtful if aeroplanes will ever cross the ocean...The public has...[imagined] that in another generation they will be able to fly over to London in a day. This is manifestly impossible.” —William Pickering, a Harvard astronomer, 1908i “Why shouldn’t I fly from New York to Paris?”ii —Charles A. Lindbergh on the St. Louis-Chicago Airmail run, September 1926 “To claim that...[a rocket could travel to the Moon] is to deny a fundamental law of dynamics.” —An editorial in The New York Times, January 13, 1920 “Houston, Tranquility Base here, the Eagle has landed.” —Neil Armstrong from the Moon, July 20, 1969 CONTENTS Foreword xi IntroductIon xiii PART 1: BUILDING THE FOUNDATION, 1885 TO 1927 Chapter 1: dreams 21 Chapter 2: FluId Power 33 Chapter 3: on the western Front 47 Chapter 4: hard tImes 55 Chapter 5: startIng over 73 Chapter 6: the sPIrIt oF st. -

Usair Flight 427 Boeing 737-300, N513au Near Aliquippa, Pennsylvania September 8, 1994

PB99-910401 ‘I NTSB/AAR-99/01 DCA94MA076 NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY BOARD WASHINGTON, D.C. 20594 AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT REPORT UNCONTROLLED DESCENT AND COLLISION WITH TERRAIN USAIR FLIGHT 427 BOEING 737-300, N513AU NEAR ALIQUIPPA, PENNSYLVANIA SEPTEMBER 8, 1994 6472A Abstract: This report explains the accident involving USAir flight 427, a Boeing 737-300, which entered an uncontrolled descent and impacted terrain near Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, on September 8, 1994. Safety issues in the report focused on Boeing 737 rudder malfunctions, including rudder reversals; the adequacy of the 737 rudder system design; unusual attitude training for air carrier pilots; and flight data recorder parameters. Safety recommendations concerning these issues were addressed to the Federal Aviation Administration. The National Transportation Safety Board is an independent Federal Agency dedicated to promoting aviation, raiload, highway, marine, pipeline, and hazardous materials safety. Established in 1967, the agency is mandated by Congress through the Independent Safety Board Act of 1974 to investigate transportation accidents, study transportation safety issues, and evaluate the safety effectiveness of government agencies involved in transportation. The Safety Board makes public its actions and decisions through accident reports, safety studies, special investigation reports, safety recommendations, and statistical reviews. Recent publications are available in their entirety at http://www.ntsb.gov/. Other information about available publications may also be obtained from the Web site or by contacting: National Transportation Safety Board Public Inquiries Section, RE-51 490 L’Enfant Plaza, East, S.W. Washington, D.C. 20594 Safety Board publications may be purchased, by individual copy or by subscription, from the National Technical Information Service. -

Controlled Flight Into Terrain: a Study of Pilot Perspectives in Alaska

FLIGHT SAFETY FOUNDATION NOVEMBER–DECEMBER 2001 FLIGHT SAFETY DIGEST Controlled Flight Into Terrain: A Study of Pilot Perspectives in Alaska Among U.S. States, Alaska Has Highest Incidence of Accidents in FARs Part 135 Operations SINCE 1947 FLIGHT SAFETY FOUNDATION For Everyone Concerned With the Safety of Flight Flight Safety Digest Officers and Staff Vol. 20 No. 11–12 November–December 2001 Hon. Carl W. Vogt Chairman, Board of Governors In This Issue Stuart Matthews President and CEO Controlled Flight Into Terrain: Robert H. Vandel 1 Executive Vice President A Study of Pilot Perspectives in Alaska James S. Waugh Jr. Survey results indicate that pilots employed by companies Treasurer involved in controlled-flight-into-terrain (CFIT) accidents rated their company’s safety climate and practices significantly lower ADMINISTRATIVE than pilots employed by companies that had not been involved Ellen Plaugher in CFIT accidents. Executive Assistant Linda Crowley Horger Among U.S. States, Alaska Has Manager, Support Services Highest Incidence of Accidents in 43 FINANCIAL FARs Part 135 Operations Crystal N. Phillips Since the early 1980s, about 30 percent of accidents involving Director of Finance and Administration U.S. Federal Aviation Regulations Part 135 operations in the 50 TECHNICAL U.S. states have occurred in Alaska. Results from an informal survey of Alaskan pilots indicate that external pressures to fly James Burin in marginal conditions and inadequate training are among the Director of Technical Programs factors affecting safety. Joanne Anderson Technical Programs Specialist Accident Rates Decrease Louis A. Sorrentino III 63 Managing Director of Internal Evaluation Programs Among U.S. Carriers in 2000 Robert Feeler Preliminary data from the U.S. -

In the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit ______

Case: 17-3006 Document: 003112841851 Page: 1 Date Filed: 02/01/2018 No. 17-3006 In the United States Court of Appeals For the Third Circuit _________________________________________ JILL SIKKELEE, Individually and as Personal Representative of the Estate of David Sikkelee, Deceased, Plaintiff-Appellant, V. PRECISION AIRMOTIVE CORPORATION; PRECISION AIRMOTIVE LLC; BURNS INTERNATIONAL SERVICES CORPORATION; TEXTRON LYCOMING RECIPROCATING ENGINE DIV.; AVCO CORPORATION; KELLY AEROSPACE, INC.; KELLY AEROSPACE Defendants-Appellees. _________________________________________ On Appeal from the United States District Court for the Middle District of Pennsylvania (D.C. No. 4:07-cv-00886) District Judge: Honorable Matthew W. Brann BRIEF OF THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION FOR JUSTICE AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT AND REVERSAL ________________________________________________________________________ Kathleen L. Nastri Jeffrey R. White President American Association for Justice American Association for Justice 777 6th Street NW, Suite 200 777 6th Street NW, Suite 200 Washington, DC 20001 Washington, DC 20001 Phone: (202) 944-2803 Phone: (202) 965-3500 [email protected] Attorneys for Amicus Curiae American Association for Justice Case: 17-3006 Document: 003112841851 Page: 2 Date Filed: 02/01/2018 CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT Pursuant to Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure 26.1, Amicus Curiae hereby provides the following disclosure statement: The American Association for Justice (“AAJ”) is a non-profit voluntary national bar association. There is no parent corporation or publicly owned corporation that owns ten percent or more of this entity’s stock. Respectfully submitted this 1st day of February, 2018. /s/ Jeffrey White Jeffrey R. White Attorney for Amicus Curiae ii Case: 17-3006 Document: 003112841851 Page: 3 Date Filed: 02/01/2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT ................................................. -

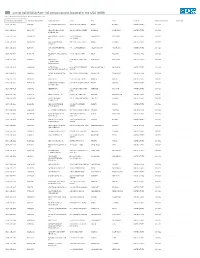

Airbus-Approved-Suppliers-List.Pdf

AIRBUS APPROVAL SUPPLIERS LIST 01 September 2021 AIRBUS APPROVAL SUPPLIERS LIST 01 September 2021 Country CAGE / Company Name code Street City Region Product Group 276086 2MATECH # 19 AVENUE BLAISE PASCAL AUBIERE France AFM-003-4 TEST LAB 305864 3A COMPOSITES GMBH # ALUSINGENPLATZ 1 SINGEN Germany AFM-002-2 MATERIAL PART MANUFACTURING 299679 3D ICOM GMBH & CO KG D3402 GEORG-HEYKEN-STR. 6 HAMBURG Germany AFM-001-2 AEROSTRUCTURE BUILD TO PRINT 309633 3D ICOM GMBH & CO KG # ZUM FLIEGERHORST 11 GROSSENHAIN Germany AFM-001-2 AEROSTRUCTURE BUILD TO PRINT 271379 3M ASD DIVISON PLANT # 801 NO MARQUETTE PRAIRIE DU CHIEN USA AFM-002-2 MATERIAL PART MANUFACTURING 285419 3M CO 8M369 610 N COUNTY RD 19 ABERDEEN USA AFM-002-2 MATERIAL PART MANUFACTURING 133367 3M COMPANY 6A670 3211 EAST CHESTNUT EXPRESS WAY SPRINGFIELD USA AFM-002-2 MATERIAL PART MANUFACTURING 305720 3M COMPANY 68293 2120 E AUSTIN BLVD NEVADA USA AFM-002-2 MATERIAL PART MANUFACTURING 133370 3M DEUTSCHLAND GMBH DL851 DUESSELDORFER STR. 121-125 HILDEN Germany AFM-002-2 MATERIAL PART MANUFACTURING 230295 3M DEUTSCHLAND GMBH D2607 CARL SCHURZ STR. 1 NEUSS Germany AFM-002-1 MATERIAL DISTRIBUTION 133374 3M ESPANA SL 0211B CL JUAN IGNACIO LUCA DE TENA 19-25 MADRID Spain AFM-002-2 MATERIAL PART MANUFACTURING 311744 3M FAIRMONT 5K231 710 N STATE STREET FAIRMONT USA AFM-002-2 MATERIAL PART MANUFACTURING 133379 3M FRANCE F0347 ROUTE DE SANCOURT TILLOY LEZ CAMBRAI France AFM-002-2 MATERIAL PART MANUFACTURING 308272 3M FRANCE # AVENUE BOULE BEAUCHAMP France AFM-003-4 TEST LAB 133376 3M FRANCE SA -

List of Valid EASA Part-145 Organisations Located in the USA (WEB) List of Valid EASA Part-145 Organisations Located in the USA

List of valid EASA Part-145 organisations located in the USA (WEB) List of valid EASA Part-145 organisations located in the USA EASA Approval Number FAA repair Station Nbr. Company name Street City State Country Continuation Date Extension EASA.145.4001 A0YR197L "A" SYSTEM HYDRAULICS, 7885 N.W. 56TH STREET MIAMI FLORIDA UNITED STATES 30/01/23 Inc. EASA.145.4002 RB1R197K VELOCITY AEROSPACE - 2840 N. ONTARIO STREET BURBANK CALIFORNIA UNITED STATES 31/07/22 BURBANK, INC. EASA.145.4003 QW1R441K AAR AIRCRAFT SERVICES, 747 ZECKENDORF GARDEN CITY NEW YORK UNITED STATES 31/07/22 Inc. BOULEVARD EASA.145.4007 VQ4R605M AAR LANDING GEAR 9371 N.W. 100TH STREET MIAMI FLORIDA UNITED STATES 31/07/22 SERVICES EASA.145.4008 JR2R936K AAR AIRCRAFT SERVICES, 6611 SOUTH MERIDIAN OKLAHOMA CITY OKLAHOMA UNITED STATES 31/01/23 Inc. EASA.145.4010 A1LR190N ABLE AEROSPACE SERVICE… 7706 E. VELOCITY WAY MESA ARIZONA UNITED STATES 31/07/23 Inc. EASA.145.4014 Y4AR0390 ACCESSORY 41 MERCEDES WAY, UNIT EDGEWOOD NEW YORK UNITED STATES 31/07/22 TECHNOLOGIES 34 CORPORATION EASA.145.4015 QAPR054K ACE PRECISION W146 N5714 ENTERPRISE MENOMONEE FALLS WISCONSIN UNITED STATES 31/01/23 MACHINING CORPORATION AVENUE EASA.145.4016 A23R362J ADAMS RITE AEROSPACE, 4141 NORTH PALM STREET FULLERTON CALIFORNIA UNITED STATES 31/01/22 Inc. EASA.145.4019 002R064L AMETEK, Inc. 4550 SOUTHEAST BLVD. WICHITA KANSAS UNITED STATES 31/07/22 EASA.145.4020 ZT3R036M TURBINEAERO ENGINES 2015 WEST ALAMEDA DRIVE TEMPE ARIZONA UNITED STATES 31/07/22 TECHNICS, INC. EASA.145.4025 SV2R175L AEE/EMF, INC 102 N.W. -

Staying Focused

STAYING FOCUSED 2008/09 ANNUAL REPORT mission statement SIA Engineering Company is engaged in providing aviation engineering services of the highest quality, at competitive prices for customers and at a profit to the company. company profile As a leading maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO) organisation with a reputation for technical and operational excellence, SIA Engineering Company offers TOTAL SUPPORT solutions to an expanding client base of international air carriers. Coupled with the specialised technical expertise developed over the years, SIA Engineering Company offers its customers a high level of service and commitment, with faster turnaround and better cost efficiencies. The Company also actively seeks alliances and partnerships with industry specialists and original equipment manufacturers to extend the breadth and depth of its services in Singapore and beyond. Certified a “People Developer” by Spring Singapore, SIA Engineering Company places high priority on attracting, developing, motivating and retaining its human capital. The Company holds certifications from more than 25 airworthiness authorities worldwide, including the Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore, the Federal Aviation Administration, the European Aviation Safety Agency and the Japan Civil Aviation Bureau. Table Of Contents 01 Statistical Highlights 02 Chairman’s Statement 04 Staying Focused 06 Integrating Core Competencies with Strategic Collaborations 08 Achieving Excellence Through Our People 10 Board Of Directors 13 Executive Management 14 Operations Review 17 Corporate Data 18 Corporate Governance 38 Financials 125 Corporate Calendar 126 Notice of Annual General Meeting 131 Proxy Form 01 statistical highlights FINANCIAL STATISTICS R1 2008-09 2007-08 % Change Group ($ million) Revenue 1,045.3 1,009.6 +3.5 Expenditure 932.7 906.7 +2.9 R1 SIA Engineering Company’s financial Operating profit 112.6 102.9 +9.4 year is from 1 April to 31 March. -

I N a N E W E

SIA ENGINEERINGCOMPANY FIRSTIN A NEW ERA Annual Report 2005/06 Annual Report2005/06 SIA ENGINEERING COMPANY 31 Airline Road Singapore 819831 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.siaec.com.sg Tel: (65) 6542 3333 Fax: (65) 6546 0679 Company Registration No. 198201025C Contact Persons: Devika Rani Davar Company Secretary/Vice-President Corporate E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (65) 6541 5151 Chia Peck Yong Senior Manager Public Affairs E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (65) 6541 5134 Amidst the usual maintenance buzz in the hangars, a renewed spirit of work dynamism was injected in FY2005/06 as the Company embraced new leading-edge technologies to launch new service offerings – A380, B777-300ER and B747-400 Passenger to Freighter conversion. Indeed, we are taking off into a new era of aviation technology. CONTENTS A Meta Fusion Design Annual Report 2005/06 1 MISSION STATEMENT CORPORATE PROFILE SIA ENGINEERING COMPANY As a leading maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO) company with a reputation for technical and operational IS ENGAGED IN PROVIDING excellence, SIA Engineering Company offers TOTAL SUPPORT solutions to an expanding client base of AVIATION ENGINEERING SERVICES international air carriers. OF THE HIGHEST QUALITY, Coupled with the specialised expertise that it has developed AT COMPETITIVE PRICES FOR over the years, SIA Engineering Company offers its customers a high level of service and commitment, as well as faster CUSTOMERS AND A PROFIT turnaround and better cost efficiencies. TO THE COMPANY. The Company also actively seeks alliances and partnerships with industry specialists and original equipment manufacturers to extend the breadth and depth of its services in Singapore and beyond.