The Third Incident of JP Mercer a Collection of Short Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(NON-FILTER) KS FSC Cigarettes: Premiu

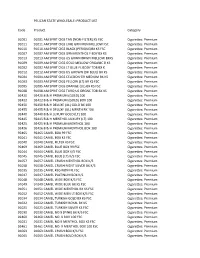

PELICAN STATE WHOLESALE: PRODUCT LIST Code Product Category 91001 91001 AM SPRIT CIGS TAN (NON‐FILTER) KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91011 91011 AM SPRIT CIGS LIME GRN MEN MELLOW FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91010 91010 AM SPRIT CIGS BLACK (PERIQUE)BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91007 91007 AM SPRIT CIGS GRN MENTHOL F BDY BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91013 91013 AM SPRIT CIGS US GRWN BRWN MELLOW BXKS Cigarettes: Premium 91009 91009 AM SPRIT CIGS GOLD MELLOW ORGANIC B KS Cigarettes: Premium 91002 91002 AM SPRIT CIGS LT BLUE FL BODY TOB BX K Cigarettes: Premium 91012 91012 AM SPRIT CIGS US GROWN (DK BLUE) BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91004 91004 AM SPRIT CIGS CELEDON GR MEDIUM BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91003 91003 AM SPRIT CIGS YELLOW (LT) BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91005 91005 AM SPRIT CIGS ORANGE (UL) BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91008 91008 AM SPRIT CIGS TURQ US ORGNC TOB BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 92420 92420 B & H PREMIUM (GOLD) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92422 92422 B & H PREMIUM (GOLD) BOX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92450 92450 B & H DELUXE (UL) GOLD BX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92455 92455 B & H DELUXE (UL) MENTH BX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92440 92440 B & H LUXURY GOLD (LT) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92445 92445 B & H MENTHOL LUXURY (LT) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92425 92425 B & H PREMIUM MENTHOL 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92426 92426 B & H PREMIUM MENTHOL BOX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92465 92465 CAMEL BOX 99 FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91041 91041 CAMEL BOX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91040 91040 CAMEL FILTER KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 92469 92469 CAMEL BLUE BOX -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Art of Eating Icecream Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1db3b9nr Author Chatterjee, Piya Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The Art of Eating Icecream A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing and Writing for the Performing Arts by Piya Chatterjee March 2015 Thesis Committee: Professor Mark Haskell-Smith, Co-Chairperson Professor Andrew Winer, Co-Chairperson Professor Tod Goldberg Copyright by Piya Chatterjee 2015 The Thesis of Piya Chatterjee is approved: ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS The Art of Eating Ice-cream by Piya Chatterjee Master of Fine Arts Graduate Program in Creative Writing and Writing for the Performing Arts University of California, Riverside, March 2015 Professor Mark Haskell-Smith, Co-Chairperson Professor Andrew Winer, Co-Chairperson In the teeming and chaotic Calcutta, Seema, a small time crook and prostitute becomes a surrogate for a gay American couple. About to give birth to a Caucasian child, Seema realizes that the birth fathers, Bill and Dave are not going to show up. Terrified but always resourceful, Seema leaves the child at the door- step of Sunil and Bethie, who have tragically lost their own baby to still birth, and desperately want a family. Bethie, so recently depressed and suicidal, is delighted to have finally found motherhood in India and Sunil swallows his misgivings for the sake of his adored wife. -

Product Catalog

2018 OUR PRODUCT LINE INCLUDES: • Automotive Merchandise • Beverages • Candy • Cigarettes • Cigars • Cleaning Supplies • Dry Groceries • General Merchandise • Health & Beauty Care • Hookah • Medicines • Smoking Accessories • Snacks • Store Supplies • Tobacco Since 1941, James J. Duffy Inc. has been servicing retailers in Eastern Massachusetts with quality candy and tobacco products at a first class level of service you will only find in a family business that has been in business for 4 generations. This past year we have been striving to upgrade our technology to better serve you, our business partners. We have upgraded computers, software, and have added online ordering. Our mission is to provide quality service at an affordable price to all of our customers. Our staff will conduct themselves at all times in a professional manner and assist our retailers where needed. We will strive to expand our product lines to make available the latest items. Our passion to succeed and improve can only be achieved by our customer’s success. TO PLACE AN ORDER OR CONTACT A DUFFY SALESPERSON: CALL 617-242-0094 FAX 617-242-0099 EMAIL [email protected] WEB www.jamesjduffy.com Page 2 • James J. Duffy Inc. • 617-242-0094 • 781-219-0000 • www.jamesjduffy.com INDEX 1. Candy .25 30. Deodorants 1. Novelties 30. Shaving 6. Gum 31. Oral Hygiene 7. Mints 31. Personal Care 7. Count Goods 32. Body Lotion 11. Cough Drops 32. Hair Products 11. Antacids 33. Body Care 11. Changemakers 33. Cleaning Supplies 12. Peg Bags 34. Detergents 13. King Size 35. Plastic Bags 14. Sathers 35. Paper Bags 14. -

Federal Leather Company Is Sold to Textron Corporation

Look M a ; N o Hands Announce Merger O f7 Federal Leather Company Is DeW itt Savings And Sold To Textron Corporation N o rth Belleville G roup Sale Of Local Plant Involves Two Local Savings And Loan Associations Reveal LOCAL DEMOCRATS Proposed Merger Approved By Directors; Special About 000,000; Fusion To Meetings Called For Full Membership Apprival ATTEND NATIONAL The proposed merger of the North Belleville Savings and Take Effect On August 31 Loan Association into the.DeWitt Saving? and Loan Associa PA R T Y CONVENTION tion has been jointly .anüapnced of th e The Federal Leather-Company, whose expanding pro*:; two'jnstitutions. Joseph King, president of the DeWitt Sav Town Chairman Ralph Vara perty and plants in River Road-and East Centre street lie osj ings, and H. Willard Sawyer,, prudent of the North Behe- both sides of the Nutley-BelleVille line, was acquired fora ville Savings, revealed that the merger has already been ap- M b. Mae Mead Mazza, And about $7,000^000, this week, by Textron, Inc., the fusion tp| proved by the Board e'f Directors ef- both ins^ptions.------ Leonard Ronco At Chicago become effective- on AugUst Di. In announcing' th e toaiisaoii The m erger, approved by th e Directors, would become ef tion, Louis M. Plansoen, president of the Federal Leather.! fective October 1, and would ir - Town democratic, chairman Company, said that it will not affect the operation of the subject ' "to ’ the approval of th Ralph Vara; state committee- firm ’s plant which, has now expanded to 800 employees. -

Unilever Annual Report and Accounts 2019 and Is an Exact Copy of the Printed Document Provided to Unilever’S Shareholders

Disclaimer This is a PDF version of the Unilever Annual Report and Accounts 2019 and is an exact copy of the printed document provided to Unilever’s shareholders. Certain sections of the Unilever Annual Report and Accounts 2019 have been audited. These are on pages 87 to 152, and those parts noted as audited within the Directors’ Remuneration Report on pages 66 to 72. The maintenance and integrity of the Unilever website is the responsibility of the Directors; the work carried out by the auditors does not involve consideration of these matters. Accordingly, the auditors accept no responsibility for any changes that may have occurred to the financial statements since they were initially placed on the website. Legislation in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands governing the preparation and dissemination of financial statements may differ from legislation in other jurisdictions. Except where you are a shareholder, this material is provided for information purposes only and is not, in particular, intended to confer any legal rights on you. This Annual Report and Accounts does not constitute an invitation to invest in Unilever shares. Any decisions you make in reliance on this information are solely your responsibility. The information is given as of the dates specified, is not updated, and any forward-looking statements are made subject to the reservations specified in the cautionary statement on the inside back cover of this PDF. Unilever accepts no responsibility for any information on other websites that may be accessed from this site by hyperlinks. Unilever Unilever Annual Report and Accounts 2019 and Accounts Annual Report Unilever Purpose-led, future-fit Unilever Annual Report and Accounts 2019 Unilever Annual Report and In this report Accounts 2019 This document is made up of the Strategic Report, the Governance Strategic Report Report, the Financial Statements and Notes, and Additional How our strategy is delivering value for our stakeholders Information for US Listing Purposes. -

Sankt Moritz: Nuovi Operai Non Facciamo Gli Indiani

L’UNICA FREE PRESS DELLA COMUNICAZIONE (copie scaricate ieri: 63.869) Anno III,IV, numero 112,12, martedì martedì 23 17 gennaio giugno 2008,2007, pag. 1 FROM THE DESK OF P.D. Non facciamo gli indiani Nessuna comparazione coi pellerossa d’America, proverbiali per saper tacere ed aspettare. Ci rife- riamo a quelli asiatici, che qui al Festival portano a casa il Grand Prix del Direct, e danno una gran- de lezione di democrazia e rinnovamento. Perchè l’azione del Times of India che ieri sera è stata premiata al Grand Auditorium rappresenta una dimostrazione di come si cambia un paese: usan- do anche le tecniche di comunicazione. Il grande quotidiano ha lanciato l’anno scorso una campa- gna partecipativa alla ricerca di nuovi candidati politici. Ha saputo smuovere milioni di persone, per poi lasciare che le stesse continuassero il pro- prio percorso autonomamente intorno a quel messaggio. L’India già si era messa in mostra per splendide campagne negli anni passati, basta ri- cordare gli ori per Levi’s. Ma con questo Grand Prix il paese si propone come leader anche nella gestione di discipline relazionali e multipiattaforma. Il ritardo italiano (1 short list) si manifesta anche così, oltre che nella miriade di presidenti ultreset- tantenni nelle nostre istituzioni. Tra i segni che le cose da noi non cambiano mai, ci sono anche le primarie del PD, che hanno prodotto finti nuovi candidati e vocazione alla sconfitta. Piuttosto che l’appparente rinnovamento generazionale dell’- ADC: sta producendo, in forma di rave party, il ritorno allo status quo delle grandi agenzie “pre Congresso di Vienna”. -

Seven Candidates Will Speak

BOX 1678 SI AUGUSTINE FLA The Weather January 15-19, 1966 Hi Lo Rain Sat. 80 62 Sun. 77 55 Mon. 70 46 Tues. 72 48 Wed. noon 72 45 BOCA RATON NEWS •m VOL. 11 NO. 18 Boca Raton, Florida January 20, 1966 30 "Pages PRICE Reorganization 217 'Disfranchised' Ordinances Get Approval Fourteen ordinances almost completely reorganizing the city government went whipping Must Register Again through Tuesday night, all with one grand motion. Not a voice was raised, either from councilmen or from the Notified public, as the definitive ordinances, authored by City Attorney John Quinn and based To Sign Up on the suggestions of City Man- ager L.M. McConnell, were passed. If Jan. 28 Council had already discussed the rules in detail, and Mayor The 217 people who were Sid Brodhead's solemn intoning omitted from city voting lists of "Are there any public com- when the "single registration" ments?" after each title was system started Jan. 1 will be r,et6 was only a matter of form. allowed to cast ballots in the The 14 ordinances gave auth- Feb. .1 primary, but must re- ority for revamping the build- register. ing, engineering, city clerk, City Attorney John J. Quinn budget offices, building inspec- said yesterday that a notice tion, personnel, city manager, would be sent each one of the 217 tax, public works, finance, and notifying them of the action and legal departments. asking them to re-register be- With no dissent from the pub- fore Jan. 28, when the voting lic, an act requiring the regist- lists must be prepared. -

1455189355674.Pdf

THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN Cover by: Peter Bradley LEGAL PAGE: Every effort has been made not to make use of proprietary or copyrighted materi- al. Any mention of actual commercial products in this book does not constitute an endorsement. www.trolllord.com www.chenaultandgraypublishing.com Email:[email protected] Printed in U.S.A © 2013 Chenault & Gray Publishing, LLC. All Rights Reserved. Storyteller’s Thesaurus Trademark of Cheanult & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Chenault & Gray Publishing, Troll Lord Games logos are Trademark of Chenault & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS 1 FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR 1 JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN 1 INTRODUCTION 8 WHAT MAKES THIS BOOK DIFFERENT 8 THE STORYTeller’s RESPONSIBILITY: RESEARCH 9 WHAT THIS BOOK DOES NOT CONTAIN 9 A WHISPER OF ENCOURAGEMENT 10 CHAPTER 1: CHARACTER BUILDING 11 GENDER 11 AGE 11 PHYSICAL AttRIBUTES 11 SIZE AND BODY TYPE 11 FACIAL FEATURES 12 HAIR 13 SPECIES 13 PERSONALITY 14 PHOBIAS 15 OCCUPATIONS 17 ADVENTURERS 17 CIVILIANS 18 ORGANIZATIONS 21 CHAPTER 2: CLOTHING 22 STYLES OF DRESS 22 CLOTHING PIECES 22 CLOTHING CONSTRUCTION 24 CHAPTER 3: ARCHITECTURE AND PROPERTY 25 ARCHITECTURAL STYLES AND ELEMENTS 25 BUILDING MATERIALS 26 PROPERTY TYPES 26 SPECIALTY ANATOMY 29 CHAPTER 4: FURNISHINGS 30 CHAPTER 5: EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 ADVENTurer’S GEAR 31 GENERAL EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 2 THE STORYTeller’s Thesaurus KITCHEN EQUIPMENT 35 LINENS 36 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS -

Financial Trip with a Foreign Language League Schools Group, Presents Mayor Amerigo Petrocci of Rome, Italy, with a Gift of Friendship — a Key to the City of St

Blooclmobile draws recor V Hi**?: WW church Foreign students Moore Seed Farm INSIDE: 243 pints —Page 1-B M&Page A-4 see Clinton — Page 2-B part of tour — Page 11-B —•*-»* .—£«.* m*. (* 112th Year, No. 12 ST. JOHNS, MICHIGAN - THURSDAY, JULY 13, 1967 2 SECTIONS - 32 PAGES 15 Cents WHITE MEETS ROME MAYOR Jeff White of St. Johns, on a European financial trip with a Foreign Language League Schools group, presents Mayor Amerigo Petrocci of Rome, Italy, with a gift of friendship — a key to the city of St. Johns — from Mayor Charles Coletta of St. Johns. White and Mike Galvach of St. Johns are among a group of 11 students taking the European Oh, woe, f\woe is we! trip under the guidance of Mrs Beatrice L. Barnum, St. Johns school teacher. Water rate Post office Cify may have to assess County to borrow $200,000 wants room hike would to expand for street paving affect 4 to meet operational The Post Office Department The city commission Is only wants to buy a 39 x 50 foot a step away from adopting new chunk of city property to pro water rates that would affect vide space for a future expan to complete blacktop plans the four heaviest users of water expenses for balance of '67 sion of the St. Johns Post Office. in St. Johns by an estimated The St. Johns City Commis 20 per cent to the general fund Lincoln and Gibbs; SWEGES be The/request was made to the $19,000 more per year. Clinton County will borrow $200,000 to help tide itself over sion Is considering a special at large. -

Fall Catalog for Web Site

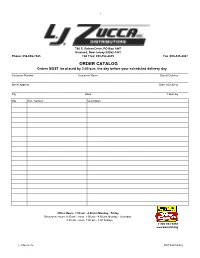

1 760 S. Delsea Drive, PO Box 1447 Vineland, New Jersey 08362-1447 Phone: 856-692-7425 Toll Free: 800-552-2639 Fax :800-443-2067 ORDER CATALOG Orders MUST be placed by 3:00 p.m. the day before your scheduled delivery day Customer Number Customer Name Day of Delivery Street Address Date of Delivery City State Taken by Qty Item number Description Office Hours: 7:00 am - 4:00 pm Monday - Friday Showroom Hours: 8:30 am - noon, 1:00 pm - 4:30 pm Monday - Thursday 8:30 am - noon, 1:00 pm - 3:00 Fridays 1-800-934-3968 www.wecard.org L J Zucca, Inc. 2007 Fall Catalog 2 Table of contents Pages Automotive Air Fresheners, Antifreeze, Gas Cans, Maps, Motor Oil, Starting Fluid, Windshiel 70-71 Beverages 35-39 Bottle water, Carbonated drinks, Sports drinks, Juices, Cigars 9-14 Boxes, Little Cigars, Packs, Premium, Twin Packs Cigarettes 4-8 25's, 100's, 120's, Generic, King's, Non Filter, Premium, Specialty Confections - Candy 22-32 Candy - Concession, Fundraiser, Gum, King Size, Mints, Nostalgic, Novelty, Peg-bags, Regular, Wrapped, Un-wrapped Dairy 84-86 Butter, Cheese, Dinners, Juice, Meats, Puddings Food Service 46-48 Cappuccino Mixes, Coffee Service, Fountain Syrups, Gallon & Bulk Items Frozen 87-89 Bagels, Cakes, Dinners, Juice, Meats, Pizza, Vegetables, Waffles, Grocery 72-84 Baby Needs, Cookies, Coffee. Condiments, Cleaning items, Laundry supplies, Pasta, Pet Food, Rice, Tea, Vegetables General Merchandise 19-21 Batteries, Duct Tape, Phone Cards, Shoe Polish, Super Glue Health & Beauty Care 56-70 Aspirin, Cold & Cough remedies, Eye care, Shampoo, Toiletries Paper 49-55 Aluminum Foil, Cups, Napkins, Plates, Towels, Trash Bags, Toilet Tissues Snacks 42-46 Chips, Cookies, Meat Snacks, Nuts, Popcorn, Pretzels, Tobacco & Tobacco Accessories 14-18 Chewing, Cigarette Papers, Lighters, Matches, Pipe, Plug, Roll-Your-Own, Snuff, Wraps, L J Zucca, Inc. -

ICP Global Core List

International Comparison Program [10.02] ICP Global Core List Global Office 3rd Technical Advisory Group Meeting June 10-11, 2010 Paris, France Basic Heading 1101111 Rice Product 110111101 Long grain rice Number of units.: 1 Unit of measurement.: Kilogram Product Specifications Min.: 0.75 Max.: 1.2 Brand.: Well known Type.: Long grain, white rice (milled rice) Packaging.: Prepacked; paper or plastic bag Quality.: High grade Preparation.: Parboiled Share of broken rice.: Very low (not more than 5%) Other features.: Not enriched, not aromatic (fragrant), not sticky Exclude.: Premium rice e.g. Basmati rice, jasmine rice Basic Heading 1101111 Rice Product 110111102 Long grain rice - Family Pack Number of units.: 5 Unit of measurement.: Kilogram Product Specifications Min.: 4 Max.: 10 Brand.: Well known Type.: Long grain, white rice (milled rice) Packaging.: Prepacked; paper or plastic bag Quality.: High grade Preparation.: Uncooked, non-parboiled Share of broken rice.: Very low (not more than 5%) Exclude.: Premium rice e.g. Basmati rice, jasmine rice Basic Heading 1101111 Rice Product 110111103 jasmine Rice Number of units.: 10 Unit of measurement.: Kilogram Product Specifications Min.: 6 Max.: 15 Brand.: Well known Type.: Long grain, white rice (milled rice); Basmati rice Packaging.: Bulk or Loose Quality.: High grade Preparation.: Uncooked, non-parboiled Milling.: Extra-well-milled Share of broken rice.: Very low (less than 5%) Other features.: Not enriched, aromatic (fragrant), not sticky Comments.: Specify brand ICP Global Office 2 Basic -

Oranges Bacon

PRESS-HERALD DECFMBER 26, To All of Our Wonderful The Very Best To You In 1966 From Customers Your Friends at BETTER FOOD Markets! and Friends I For Entertaining Family and Friends Choose from the very best imported and domestic cheese in th« bin BETTER FOOD Delicatessen Dept. WISCONSIN /MONTEREY jm £^f INDIVIDUALLY WRAPPED/Processed American £^ JACK CHEESE X 49 Sliced Cheese 59 FISHER'S CHEESE ^P^ Bp XLNT/Freshly Made, Finest Flavor Mb ^|k M^ 7 BIG SALE DAYS SNACK PACK X 35 Potato Salad 29 SPECIALS EFFECTIVE MOM., DEC. 27 through SUN., JAN. 2 BETTER FOOD MARKETS WILL BE CHEESE LOAF OPEN NEW YEARS DAY CHEESE Chef's Delite 24 HOURS Favorite Processed j AROUND THE CLOCK Cheddar AT REDONDO BEACH BLVD. & PRARIE American Smooth ID Spread OTHER MARKETS OPEN 9 A.M. TO 8 P.M. & Creamy *"" » A REAL VALUE! SmiNGFIELD/PASTEL COLORS BOX OF CUT-UP. PAN-READY 200 I FACIAL TISSUE SHEETS FRYING t /^fON'S/GREAT FOR SNACK DIPS, TOO ^ Onion Soup Mix CHICKEN U.S.D.A. GOLDEN CREME/FOR HOLIDAY DIPS « DESSERTS Freih or Frozen SOUR CREAM «» Tender, Meaty Young Fryers BONUS PACK/TWO OUNCES EXTRA NESCAFE INSTANT COFFIE FRESH YOUNG SPLIT BROILERS I DOG FOOD/REGULAR or LIVER 15-OZ. TALL Save lie Extra Drumsticks for the Kiddies! > KEN-L RATION CAN Four-Legged Fryers lb YOUNG HONEYSUCKLE/With Giblet Gravy FRYING CHICKEN PARTS CHICKEN FRYER TURKEY SLICES BREASTS 45C WINGS POPPY BRAND/Plump, Young BANANAS LEGS or 45e BACKS >nd » Mf*~ THIGHS BACKS 5 49C DUCKLINGS Firm, Golden Ripe Dublin Brand Lean and lb.