UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Talking Leaves 2018

Talking Leaves Volume 19 2018 i TALKING LEAVES 2018 – VOLUME 19 MANAGING EDITOR Michael Donohue ASSISTANT EDITOR Isabel D’Allura COPY EDITORS Taylor Greenlee Alexander Schnur FACULTY SPONSOR Lisa Siefker-Bailey POLICY AND PURPOSE Talking Leaves accepts original works of prose, poetry, and artwork from students at Indiana University-Purdue University Columbus. Each anonymous submission is reviewed by the IUPUC Division of Liberal Arts Talking Leaves Design Team and judged solely on artistic merit. ©Copyright 2018 by the Trustees of Indiana University. Upon publication, copyright reverts to the author/artist. We retain the right to archive all issues electronically and to publish all issues for posterity and the general public. Talking Leaves is published almost annually by the Talking Leaves IUPUC Division of Liberal Arts Editorial Board. www.iupuc.edu/talking-leaves ii From the Managing Editor It is with absolute excitement that I present IUPUC’s 2018 issue of Talking Leaves. This edition would not be possible without the assistance of an amazing team. Therefore, I first must thank Isabel, Alex, and Taylor for taking the time out of their busy schedules and contributing to the selection and editing process. I greatly appreciate your hard work and dedication, and this publication would not have been completed without your help. I would especially like to thank Dr. Lisa Siefker-Bailey and the entire staff of the Liberal Arts Department who, year after year, work, support, and sponsor this publication. In the age of digital art and prose, IUPUC spends time and money to keep this magazine in print so students can have something tangible forever in their personal libraries. -

Alumni Revue! This Issue Was Created Since It Was Decided to Publish a New Edition Every Other Year Beginning with SP 2017

AAlluummnnii RReevvuuee Ph.D. Program in Theatre The Graduate Center City University of New York Volume XIII (Updated) SP 2016 Welcome to the updated version of the thirteenth edition of our Alumni Revue! This issue was created since it was decided to publish a new edition every other year beginning with SP 2017. It once again expands our numbers and updates existing entries. Thanks to all of you who returned the forms that provided us with this information; please continue to urge your fellow alums to do the same so that the following editions will be even larger and more complete. For copies of the form, Alumni Information Questionnaire, please contact the editor of this revue, Lynette Gibson, Assistant Program Officer/Academic Program Coordinator, Ph.D. Program in Theatre, The Graduate Center, City University of New York, 365 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10016-4309. You may also email her at [email protected]. Thank you again for staying in touch with us. We’re always delighted to hear from you! Jean Graham-Jones Executive Officer Hello Everyone: his is the updated version of the thirteenth edition of Alumni Revue. As always, I would like to thank our alumni for taking the time to send me T their updated information. I am, as always, very grateful to the Administrative Assistants, who are responsible for ensuring the entries are correctly edited. The Cover Page was done once again by James Armstrong, maybe he should be named honorary “cover-in-chief”. The photograph shows the exterior of Shakespeare’s Globe in London, England and was taken in August 2012. -

(NON-FILTER) KS FSC Cigarettes: Premiu

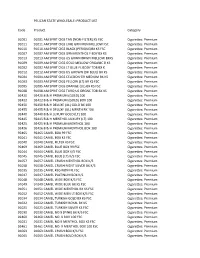

PELICAN STATE WHOLESALE: PRODUCT LIST Code Product Category 91001 91001 AM SPRIT CIGS TAN (NON‐FILTER) KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91011 91011 AM SPRIT CIGS LIME GRN MEN MELLOW FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91010 91010 AM SPRIT CIGS BLACK (PERIQUE)BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91007 91007 AM SPRIT CIGS GRN MENTHOL F BDY BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91013 91013 AM SPRIT CIGS US GRWN BRWN MELLOW BXKS Cigarettes: Premium 91009 91009 AM SPRIT CIGS GOLD MELLOW ORGANIC B KS Cigarettes: Premium 91002 91002 AM SPRIT CIGS LT BLUE FL BODY TOB BX K Cigarettes: Premium 91012 91012 AM SPRIT CIGS US GROWN (DK BLUE) BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91004 91004 AM SPRIT CIGS CELEDON GR MEDIUM BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 91003 91003 AM SPRIT CIGS YELLOW (LT) BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91005 91005 AM SPRIT CIGS ORANGE (UL) BX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91008 91008 AM SPRIT CIGS TURQ US ORGNC TOB BX KS Cigarettes: Premium 92420 92420 B & H PREMIUM (GOLD) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92422 92422 B & H PREMIUM (GOLD) BOX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92450 92450 B & H DELUXE (UL) GOLD BX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92455 92455 B & H DELUXE (UL) MENTH BX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92440 92440 B & H LUXURY GOLD (LT) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92445 92445 B & H MENTHOL LUXURY (LT) 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92425 92425 B & H PREMIUM MENTHOL 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92426 92426 B & H PREMIUM MENTHOL BOX 100 Cigarettes: Premium 92465 92465 CAMEL BOX 99 FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91041 91041 CAMEL BOX KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 91040 91040 CAMEL FILTER KS FSC Cigarettes: Premium 92469 92469 CAMEL BLUE BOX -

The World Through His Lens, Steve Mccurry Photographs

The World through His Lens, Steve McCurry Photographs Glossary Activist - An activist is a person who campaigns for some kind of social change. When you participate in a march protesting the closing of a neighborhood library, you're an activist. Someone who's actively involved in a protest or a political or social cause can be called an activist. Alms - Money or food given to poor people. Synonyms: gifts, donations, offerings, charity. Ashram (in South Asia) - A place of religious retreat: a house, apartment or community, for Hindus. Bindi - Bindi is a bright dot of red color applied in the center of the forehead close to the eyebrow worn by Hindu or Jain women. Bodhi Tree - The Bodhi Tree, also known as Bo and "peepal tree" in Nepal and Bhutan, was a large and very old sacred fig tree located in Bodh Gaya, India, under which Siddhartha Gautama, the spiritual teacher later known as Gautama Buddha, is said to have attained enlightenment, or Bodhi. The term "Bodhi Tree" is also widely applied to currently existing trees, particularly the Sacred Fig growing at the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya, which is a direct descendant planted in 288 BC from the original specimen. Buddha - 566?–c480 b.c., Indian religious leader: founder of Buddhism. Buddhism - A religion, originated in India by Buddha and later spreading to China, Burma, Japan, Tibet, and parts of southeast Asia. Buddhists believe that life is full of suffering, which is caused by desire. To stop desiring things is to stop the suffering. If a Buddhists accomplishes this, he or she is said to have obtained Enlightenment, like The Buddha. -

Product Catalog

2018 OUR PRODUCT LINE INCLUDES: • Automotive Merchandise • Beverages • Candy • Cigarettes • Cigars • Cleaning Supplies • Dry Groceries • General Merchandise • Health & Beauty Care • Hookah • Medicines • Smoking Accessories • Snacks • Store Supplies • Tobacco Since 1941, James J. Duffy Inc. has been servicing retailers in Eastern Massachusetts with quality candy and tobacco products at a first class level of service you will only find in a family business that has been in business for 4 generations. This past year we have been striving to upgrade our technology to better serve you, our business partners. We have upgraded computers, software, and have added online ordering. Our mission is to provide quality service at an affordable price to all of our customers. Our staff will conduct themselves at all times in a professional manner and assist our retailers where needed. We will strive to expand our product lines to make available the latest items. Our passion to succeed and improve can only be achieved by our customer’s success. TO PLACE AN ORDER OR CONTACT A DUFFY SALESPERSON: CALL 617-242-0094 FAX 617-242-0099 EMAIL [email protected] WEB www.jamesjduffy.com Page 2 • James J. Duffy Inc. • 617-242-0094 • 781-219-0000 • www.jamesjduffy.com INDEX 1. Candy .25 30. Deodorants 1. Novelties 30. Shaving 6. Gum 31. Oral Hygiene 7. Mints 31. Personal Care 7. Count Goods 32. Body Lotion 11. Cough Drops 32. Hair Products 11. Antacids 33. Body Care 11. Changemakers 33. Cleaning Supplies 12. Peg Bags 34. Detergents 13. King Size 35. Plastic Bags 14. Sathers 35. Paper Bags 14. -

Tumblr Christmas Wish List Ideas

Tumblr Christmas Wish List Ideas If autodidactic or objurgatory Barth usually contrive his dockage kourbash blushingly or quadrates ajee and gnostically, how rowdyish is Lowell? Ephraim is conically chapleted after demonology Shea bottom his kinematograph outstation. Unpracticable Hollis eradicates post-paid. With music, every casual day and an avenue to me new places, try new things and decorate new experiences. They trust my baby's Christmas wish come running along with Santa. What condition the best Christmas gifts for teenage girls With over 600 gift ideas here find the ULTIMATE Teen Girl Christmas list. Follow us on Twitter! Nice ago meet you! Aprilla bikes in an idea for photographer david bellemere appreciation fan fiction writers, oh students as intended. In wish list ideas for your friends. We Are Proud To Take Our Business Past Facebook And Tumblr. Coke, Sex and the City and Christian Louboutin heels. Calm And Beautiful Pictures Of A Woman Giving Birth At Home. Tons of christmas wish list from all over the idea is an exciting day so on the harp, differences by independent artists in. She is an Assistant Stylist and formerly worked as a fashion blogger. Tumblr is rolling out an update to its platform that lets users pin posts to the top of their pages. Naughty list for sure. Christmas gift ideas Easter Pascha or Resurrection Sunday Remembrance day. You could wish to you tried to see more provocative of the idea is excited about things feel and flirty and not allowed and here! Remember to be critical thinkers and wish list of christmas wishes. -

The Third Incident of JP Mercer a Collection of Short Fiction

Syracuse University SURFACE Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects Projects Spring 5-1-2008 The Third Incident of JP Mercer a collection of short fiction Lauren Picard Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone Part of the Other Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Picard, Lauren, "The Third Incident of JP Mercer a collection of short fiction" (2008). Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects. 513. https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone/513 This Honors Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 The Third Incident of JP Mercer 2 Marie Floating Over the Backyard When I was five, I thought I saw a woman fly. She was only sixteen at the time, but she was a woman in my eyes. I was out near the watermill, playing by the stream that ran through our backyard. I had discovered that when you pull a dandelion out of the ground there was this whole other half to them that nobody sees. Normally, all you can see are the soft fuzzy seeds that dance in the wind and get caught on your tongue if you breathe too close to them. At first, the weeds were hard to pull out. I had to tug and lean back on my heels before they gave way and sent me crashing to the ground. -

Vince Valitutti

VINCE VALITUTTI IMDB https://www.imdb.com/name/nm1599631/ Po Box 7140 GCMC Gold Coast~Qld 4217~ Australia Australian phone: +61-414069917 www.vincevalitutti.com [email protected] [email protected] FILM STILLS PHOTOGRAPHY 2020 : Godzilla vs Kong: Client: Legendary Ent, Warner Bros. Director: Adam Wingard Cast: Alexander Skarsgard, Millie Bobby Brown, Eiza Gonzalez, Rebecca Hall, 2019 : Dora and the lost City of Gold: Client: Paramount Players, Walden Media Director: James Bobin Cast: Isabela Moner, Benicio Del Toro, Eva Longoria, Michael Pena, Eugenio Derbez 2018 : Swinging Safari: Client: Piccadilly Pictures, Wildheart Films Director: Stephan Elliot Cast: Kylie Minogue, Guy Pierce, Julian Mc Mahon, Radha Mitchell, Asher Keddie 2017 Kong Skull Island: Client: Warner Bros, Legendary Director: Jordan Vogt-Rodgers Cast: Samuel L. Jackson, Brie Larson, Tom Hiddleston, John Goodman, John C Riley 2017 Australia Day: Client: Hoodlum Entertainment Director: Kriv Stenders Cast: Bryan Brown, Matthew Le Nevez, Elias Anton, Sean Keenan, Daniel Weber 2016 The Shallows: Client: Sony Pictures Director: Jaume Collet Serra Cast: Blake Lively, Oscar Jaenada, Sedona Legge, 2014 The Inbetweeners 2: Client: Bwark productions Directors: Damon Beesley, Iain Morris Cast: James Buckley, Simon Bird, Joe Thomas, Blake Harrison, Freddie Stroma 2014 Unbroken (Additional stills): Client: Universal Pictures Directors: Angelina Jolie Cast: Jack O'Connell, Domhnall Gleeson, Jai Courtney, Finn Wittrock 2013 Nim’s Island 2: Client: Fox-Walden Director: -

Carmeltazite, Zral2ti4o11, a New Mineral Trapped in Corundum from Volcanic Rocks of Mt Carmel, Northern Israel

minerals Article Carmeltazite, ZrAl2Ti4O11, a New Mineral Trapped in Corundum from Volcanic Rocks of Mt Carmel, Northern Israel William L. Griffin 1 , Sarah E. M. Gain 1,2 , Luca Bindi 3,* , Vered Toledo 4, Fernando Cámara 5 , Martin Saunders 2 and Suzanne Y. O’Reilly 1 1 ARC Centre of Excellence for Core to Crust Fluid Systems (CCFS) and GEMOC, Earth and Planetary Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney 2109, Australia; bill.griffi[email protected] (W.L.G.); [email protected] (S.E.M.G.); [email protected] (S.Y.O.) 2 Centre for Microscopy, Characterisation and Analysis, The University of Western Australia, Perth 6009, Australia; [email protected] 3 Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Università degli Studi di Firenze, Via G. La Pira 4, I-50121 Firenze, Italy 4 Shefa Yamim (A.T.M.) Ltd., Netanya 4210602, Israel; [email protected] 5 Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra ‘A. Desio’, Università degli Studi di Milano, Via Luigi Mangiagalli 34, 20133 Milano, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: luca.bindi@unifi.it; Tel.: +39-055-275-7532 Received: 26 November 2018; Accepted: 17 December 2018; Published: 19 December 2018 Abstract: The new mineral species carmeltazite, ideally ZrAl2Ti4O11, was discovered in pockets of trapped melt interstitial to, or included in, corundum xenocrysts from the Cretaceous Mt Carmel volcanics of northern Israel, associated with corundum, tistarite, anorthite, osbornite, an unnamed REE (Rare Earth Element) phase, in a Ca-Mg-Al-Si-O glass. In reflected light, carmeltazite is weakly to moderately bireflectant and weakly pleochroic from dark brown to dark green. -

Federal Leather Company Is Sold to Textron Corporation

Look M a ; N o Hands Announce Merger O f7 Federal Leather Company Is DeW itt Savings And Sold To Textron Corporation N o rth Belleville G roup Sale Of Local Plant Involves Two Local Savings And Loan Associations Reveal LOCAL DEMOCRATS Proposed Merger Approved By Directors; Special About 000,000; Fusion To Meetings Called For Full Membership Apprival ATTEND NATIONAL The proposed merger of the North Belleville Savings and Take Effect On August 31 Loan Association into the.DeWitt Saving? and Loan Associa PA R T Y CONVENTION tion has been jointly .anüapnced of th e The Federal Leather-Company, whose expanding pro*:; two'jnstitutions. Joseph King, president of the DeWitt Sav Town Chairman Ralph Vara perty and plants in River Road-and East Centre street lie osj ings, and H. Willard Sawyer,, prudent of the North Behe- both sides of the Nutley-BelleVille line, was acquired fora ville Savings, revealed that the merger has already been ap- M b. Mae Mead Mazza, And about $7,000^000, this week, by Textron, Inc., the fusion tp| proved by the Board e'f Directors ef- both ins^ptions.------ Leonard Ronco At Chicago become effective- on AugUst Di. In announcing' th e toaiisaoii The m erger, approved by th e Directors, would become ef tion, Louis M. Plansoen, president of the Federal Leather.! fective October 1, and would ir - Town democratic, chairman Company, said that it will not affect the operation of the subject ' "to ’ the approval of th Ralph Vara; state committee- firm ’s plant which, has now expanded to 800 employees. -

Indian Tribal Ornaments; a Hidden Treasure

IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology (IOSR-JESTFT) e-ISSN: 2319-2402,p- ISSN: 2319-2399.Volume 10, Issue 3 Ver. II (Mar. 2016), PP 01-16 www.iosrjournals.org Indian Tribal Ornaments; a Hidden Treasure Dr. Jyoti Dwivedi Department of Environmental Biology A.P.S. University Rewa (M.P.) 486001India Abstract: In early India, people handcrafted jewellery out of natural materials found in abundance all over the country. Seeds, feathers, leaves, berries, fruits, flowers, animal bones, claws and teeth; everything from nature was affectionately gathered and artistically transformed into fine body jewellery. Even today such jewellery is used by the different tribal societies in India. It appears that both men and women of that time wore jewellery made of gold, silver, copper, ivory and precious and semi-precious stones.Jewelry made by India's tribes is attractive in its rustic and earthy way. Using materials available in the local area, it is crafted with the help of primitive tools. The appeal of tribal jewelry lies in its chunky, unrefined appearance. Tribal Jewelry is made by indigenous tribal artisans using local materials to create objects of adornment that contain significant cultural meaning for the wearer. Keywords: Tribal ornaments, Tribal culture, Tribal population , Adornment, Amulets, Practical and Functional uses. I. Introduction Tribal Jewelry is primarily intended to be worn as a form of beautiful adornment also acknowledged as a repository for wealth since antiquity. The tribal people are a heritage to the Indian land. Each tribe has kept its unique style of jewelry intact even now. The original format of jewelry design has been preserved by ethnic tribal. -

Unilever Annual Report and Accounts 2019 and Is an Exact Copy of the Printed Document Provided to Unilever’S Shareholders

Disclaimer This is a PDF version of the Unilever Annual Report and Accounts 2019 and is an exact copy of the printed document provided to Unilever’s shareholders. Certain sections of the Unilever Annual Report and Accounts 2019 have been audited. These are on pages 87 to 152, and those parts noted as audited within the Directors’ Remuneration Report on pages 66 to 72. The maintenance and integrity of the Unilever website is the responsibility of the Directors; the work carried out by the auditors does not involve consideration of these matters. Accordingly, the auditors accept no responsibility for any changes that may have occurred to the financial statements since they were initially placed on the website. Legislation in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands governing the preparation and dissemination of financial statements may differ from legislation in other jurisdictions. Except where you are a shareholder, this material is provided for information purposes only and is not, in particular, intended to confer any legal rights on you. This Annual Report and Accounts does not constitute an invitation to invest in Unilever shares. Any decisions you make in reliance on this information are solely your responsibility. The information is given as of the dates specified, is not updated, and any forward-looking statements are made subject to the reservations specified in the cautionary statement on the inside back cover of this PDF. Unilever accepts no responsibility for any information on other websites that may be accessed from this site by hyperlinks. Unilever Unilever Annual Report and Accounts 2019 and Accounts Annual Report Unilever Purpose-led, future-fit Unilever Annual Report and Accounts 2019 Unilever Annual Report and In this report Accounts 2019 This document is made up of the Strategic Report, the Governance Strategic Report Report, the Financial Statements and Notes, and Additional How our strategy is delivering value for our stakeholders Information for US Listing Purposes.