1 Efficiency in Local Service Delivery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

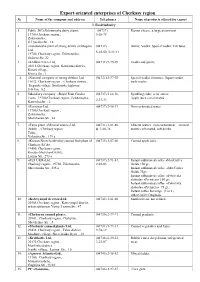

Export-Oriented Enterprises of Cherkasy Region № Name of the Company and Address Telephones Name of Products Offered for Export I

Export-oriented enterprises of Cherkasy region № Name of the company and address Telephones Name of products offered for export I. Food industry 1. Public JSC«Zolotonosha dairy plant», (04737) Rennet cheese, a large assortment 19700,Cherkasy region., 5-26-78 Zolotonosha , G.Lysenko Str., 18 2. «Zolotonosha plant of strong drinks «Zlatogor» (04737) Balms; Vodka; Special vodka; Tinctures. Ltd, 5-23-50, 5-39-41 19700, Cherkasy region, Zolotonosha, Sichova Str, 22 3. «Khlibna Niva» Ltd, (04732) 9-79-69 Vodka and spirits. 20813,Cherkasy region, Kamianka district, Kosari village, Kirova Str., 1 4. «National company of strong drinks» Ltd, (0472) 63-37-70 Special vodka, tinctures, liquers under 19632, Cherkasy region., Cherkasy district , trade marks. Stepanki village, Smilianske highway, 8-th km, б.2 5. Subsidiary company «Royal Fruit Garden (04737) 5-64-26, Sparkling cider, semi-sweet; East», 19700,Cherkasy region, Zolotonosha, Apple juice concentrated 2-27-73 Kanivska Str. , 2 6. «Econiya» Ltd, (04737) 2-16-37 Non-carbonated water. 19700,Cherkasy region , Zolotonosha , Shevchenko Str., 24 7. «Talne plant «Mineral waters»Ltd., (04731) 3-01-88, Mineral waters non-carbonated, mineral 20400, ., Cherkasy region ф. 3-08-36 waters carbonated, soft drinks Talne, Voksalna Str., 139 а 8. «Korsun-Shevchenkivskiy canned fruit plant of (04735) 2-07-60 Canned apple juice Cherkasy RCA», 19400, Cherkasy region., Korsun-Shevchenkivskiy, Lenina Str., 273 а 9. «FES UKR»Ltd, (04737) 2-91-84, Instant sublimated coffee «MacCoffee Cherkasy region., 19700, Zolotonosha, 2-92-03 Gold» 150 gr; Shevchenka Str., 235 а Instant sublimated coffee «MacCoffee Gold» 75gr; Instant sublimated coffee «Petrovska sloboda» «Premiera» 150 gr; Instant sublimated coffee «Petrovska sloboda» «Premiera» 75 gr.; Instant coffee beverage (3 in 1) «MacCoffee Original». -

The Book of Little Changes

THE BOOK OF LITTLE CHANGES . KYIV - 2020 CONTENTS Lviv region 39 Sokal is open. Observe and save your native town 40 Sambir is a loving city 41 SHAFA Happy Families Festival 3 Foreword 42 SVINB (Community of Free and Interested) 43 Clean City 5 What is the school “Agents of Change”? 44 Eco Day in May 6 How is the training going? 45 Smart city 46 Palms of Sincerity 7 Stages of the training 47 Find Yourself 8 Goals of the School 48 Your future 49 Warm-up → switch on 9 Partners 10 Project Team Mykolaiv region 50 STEM unlimited 11 Collection of projects 51 Cosmoport 52 We remember! Vinnytsia region 12 Creativity of Mr. Shevchenko Odesa region 13 Notumars 53 Help Box 14 Vinwriters 15 Happy childhood moment Poltava region 16 Workshop of Good Deeds 54 Dating with book 17 Bellydance 55 Upgrade yourself 18 Shawarma_party 56 YRD: your rights and duties 19 Know how to save a life 57 Iron horse 58 Happy family - strong Ukraine Dnipropetrovsk region 59 Make life brighter! 20 HappyFamilyFest 60 Open-air cinema 21 Bright stars Rivne region Zhytomyr region 61 Varashyk the Lamb is your guide to Varash city 22 Let’s save the environment 62 Crow 23 NBfest 63 Why not? 24 The Nova Borova Oscar 64 Basket of Kindness 25 My city through the camera lens Sumy region Zakarpattia region 65 Creative Workshop in Sad 26 The Camp “Camp Party” 66 Hlukhiv Mural Art 67 Book is life Zaporizhia region 27 FITA Ternopil region 28 To Stars and Mines 68 Music Wave - Reboot 29 Discover your city 69 Live Healthily 30 English Speaking Club “CrowdCloud” 31 Indoor Universe Kharkiv -

Field Trip Guidebook

Geological Survey of Norway Geoinform of Ukraine European integration of mineral raw material data (EIMIDA) joint project under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway Contract UKR-15/0006 FIELD TRIP GUIDEBOOK 1st General Workshop and Field Trip Kyiv – Zhytomyr, Ukraine May 22-27, 2016 CONTENTS Introduction........................................................................................... 3 Principal Types of Precambrian Rock Associations in the Ukrainian Shield .... 5 Sedimentary cover development in the north-west Ukrainian Shield ........... 9 A. Khoroshiv Ornamental and Gemstone Museum ..................................... 11 B. Liznykivske facing-stone granite deposit .............................................. 14 C. Mezhyrichne ilmenite placer deposit .................................................... 18 D. Ocheretyanske facing-stone labradorite deposit .................................... 24 Conclusions ......................................................................................... 30 References .......................................................................................... 31 2 Introduction The previous field trip of NUMIRE Project (May 15-22, 2013) was held in the south-east of Ukraine, Dnipropetrovsk and Zaporizhzhya regions, and in Middle-Dniprean geoblock of Ukrainian Shield (Fig. I-1). That time, the iron-ore (BIF) and manganese-ore (carbonate) deposits as well as Khortytsya granite were visited to get an impression of the area minerals. The given field trip of EIMIDA Project between Geological -

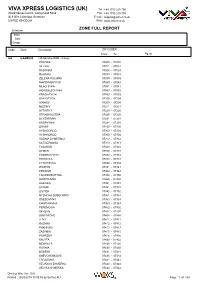

Viva Xpress Logistics (Uk)

VIVA XPRESS LOGISTICS (UK) Tel : +44 1753 210 700 World Xpress Centre, Galleymead Road Fax : +44 1753 210 709 SL3 0EN Colnbrook, Berkshire E-mail : [email protected] UNITED KINGDOM Web : www.vxlnet.co.uk Selection ZONE FULL REPORT Filter : Sort : Group : Code Zone Description ZIP CODES From To Agent UA UAAOD00 UA-Ukraine AOD - 4 days POLISKE 07000 - 07004 VILCHA 07011 - 07012 RADYNKA 07024 - 07024 RAHIVKA 07033 - 07033 ZELENA POLIANA 07035 - 07035 MAKSYMOVYCHI 07040 - 07040 MLACHIVKA 07041 - 07041 HORODESCHYNA 07053 - 07053 KRASIATYCHI 07053 - 07053 SLAVUTYCH 07100 - 07199 IVANKIV 07200 - 07204 MUSIIKY 07211 - 07211 DYTIATKY 07220 - 07220 STRAKHOLISSIA 07225 - 07225 OLYZARIVKA 07231 - 07231 KROPYVNIA 07234 - 07234 ORANE 07250 - 07250 VYSHGOROD 07300 - 07304 VYSHHOROD 07300 - 07304 RUDNIA DYMERSKA 07312 - 07312 KATIUZHANKA 07313 - 07313 TOLOKUN 07323 - 07323 DYMER 07330 - 07331 KOZAROVYCHI 07332 - 07332 HLIBOVKA 07333 - 07333 LYTVYNIVKA 07334 - 07334 ZHUKYN 07341 - 07341 PIRNOVE 07342 - 07342 TARASIVSCHYNA 07350 - 07350 HAVRYLIVKA 07350 - 07350 RAKIVKA 07351 - 07351 SYNIAK 07351 - 07351 LIUTIZH 07352 - 07352 NYZHCHA DUBECHNIA 07361 - 07361 OSESCHYNA 07363 - 07363 KHOTIANIVKA 07363 - 07363 PEREMOGA 07402 - 07402 SKYBYN 07407 - 07407 DIMYTROVE 07408 - 07408 LITKY 07411 - 07411 ROZHNY 07412 - 07412 PUKHIVKA 07413 - 07413 ZAZYMIA 07415 - 07415 POHREBY 07416 - 07416 KALYTA 07420 - 07422 MOKRETS 07425 - 07425 RUDNIA 07430 - 07430 BOBRYK 07431 - 07431 SHEVCHENKOVE 07434 - 07434 TARASIVKA 07441 - 07441 VELIKAYA DYMERKA 07442 - 07442 VELYKA -

Information of the State Property Fund of Ukraine

Information of the State Property Fund of Ukraine on conducting the auction with the terms of sale of the block of shares of the Joint-Stock Company "United Mining and Chemical Company" in the amount of 100.00% of the authorized capital 1. INFORMATION ON THE PRIVATIZATION OBJECT 1.1. Name of the privatization object: a block of shares which is 100% of the authorized capital of the Joint-Stock Company "United Mining and Chemical Company" (JSC "UMCC"). Location of the Joint-Stock Company "United Mining and Chemical Company": legal address: 03035, Kyiv city, 3 Surikova street, postal address: 01033, Kyiv city, 35 Zhylianska Street. Main activity of the Joint-Stock Company "United Mining and Chemical Company" according to NACE: 07.29 Mining of other non-ferrous metal ores; 1.2. YeDRPOU (USREOU) code: 36716128 1.3. Amount of the authorized capital of the company is: 1,944,000,000.00 UAH (one billion nine hundred forty-four million hryvnias) The nominal value of the share is 1.00 UAH. Offered for sale: state block of shares of the Joint-Stock Company "United Mining and Chemical Company" in the amount of 1,944,000,000 shares which is 100.00 % of the authorized capital of the Company. 1.4. Average staff number of the Joint-Stock Company "United Mining and Chemical Company": 5,415 persons (as of 01.05.2021). 1.5. Volume and basic product (works, services) range: 2018 2020 Name 2019 І quarter of 2021 Sales volume 329,153 297,992 95,256 including exports, thousand 307,279 242,213,687 309,711 76,107 tons Sales volume (rutile 38,860 38,367 12,139 concentrate), thousand tons 48,818 34,482 30,956 Including exports, thousand 46,406 11,554 tons Sales volume 20,438 17,910 12,480 9,794 Including exports, thousand 18,216 10,369 16,716 9,668 tons 2 1.6. -

Luftwaffe Airfields 1935-45 Russia (Incl

Luftwaffe Airfields 1935-45 Russia (incl. Ukraine, Belarus & Bessarabia) By Henry L. deZeng IV Kharkov-Rogan I Photo credit: U.S. National Archives, Photographic and Cartographic Division.; taken 14 Sept. 1941. Kharkov-Rogan I was built in 1930 for use as a military flight school. It had 8 medium and large aircraft hangars and 1 very large repair hangar, approx. 40 permanent barrack buildings, 3 workshops, admin buildings and storage structures, an oval athletic track and other facilities all grouped along the W boundary and SW corner of the landing area. There were about 10 additional structures along the S boundary that may have been for aircraft servicing and stores. Additionally, there were 22 blast bays for twin-engine and single-engine aircraft spaced along the W and S boundaries of the landing area. A separate supply dump with its own rail spur was approx. 1 km S of the airfield. Nearly all of these buildings had been destroyed or badly damaged by 1944, the majority of them blown up by the retreating Germans. Edition: February 2020 Airfields Russia (incl. Ukraine, Belarus & Bessarabia) Introduction Conventions 1. For the purpose of this reference work, “Russia” generally means the territory belonging to the country in September 1939, the month of the German attack on Poland and the generally accepted beginning of World War II, including that part of eastern Poland (i.e., Belarus, Belorussia, Weissruthenien) and western Ukraine annexed by the Soviet Union on 29 September 1939 following the USSR’s invasion of Poland on 17 September 1939. Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina were seized by the USSR between 26 June and 3 July 1940. -

Of the Public Purchasing Announcernº31 (105) July 31, 2012

Bulletin ISSN: 2078–5178 of the public purchasing AnnouncerNº31 (105) July 31, 2012 Announcements of conducting procurement procedures � � � � � � � � � 2 Announcements of procurement procedures results � � � � � � � � � � � � 44 Urgently for publication � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 103 Bulletin No�31 (105) July 31, 2012 Annoucements of conducting 16638 State JSC “NJSC “Ukragroleasing” procurement procedures 16–A Mechnykova St., 01601 Kyiv Kotenko Viacheslav Hryhorovych, Pavlovska Kristina Mykhailivna tel./fax: (044) 253–93–78; e–mail: [email protected] 16631 State JSC “NJSC “Ukragroleasing” Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: 16–A Mechnykova St., 01601 Kyiv www.tender.me.gov.ua Kotenko Viacheslav Hryhorovych, Pavlovska Kristina Mykhailivna Website which contains additional information on procurement: tel./fax: (044) 253–93–78; www.ukragroleasing.com.ua e–mail: [email protected] Procurement subject: code 29.32.6 – other agricultural machines (set Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: of equipment for maintenance of dairy cattle ОДС – 120 units) www.tender.me.gov.ua Supply/execution: on EXW terms, according to Incoterms, ex mill OJSC “Bratslav”, Website which contains additional information on procurement: 124 Lenina St., 22870 Bratslav Urban Settlement, Nemyrivskyi Rayon, www.ukragroleasing.com.ua Vinnytsia Oblast; August – December 2012 Procurement subject: code 29.31.2 – agricultural and forestry -

Training Needs Analysis of Local Self-Government Authorities of Ukraine

COUNCIL OF EUROPE PROGRAMME “DECENTRALISATION AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT REFORM IN UKRAINE” TRAINING NEEDS ANALYSIS OF LOCAL SELF-GOVERNMENT AUTHORITIES OF UKRAINE ANALYTICAL REPORT Nataliia Baldych Nataliya Hnydiuk Cezary Trutkowski April 2019 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of abbreviations ....................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary........................................................................................................................ 5 About this report ......................................................................................................................... 5 Key findings ............................................................................................................................... 5 Recommendations .....................................................................................................................10 1. Introduction ...............................................................................................................................12 1.1. Purpose and objective of the research ..................................................................................12 1.2. Methodology.......................................................................................................................12 2. Legal and institutional framework for amalgamated communities ..............................................15 2.1. Establishment of amalgamated territorial communities........................................................15 -

Of the Public Purchasing Announcernº38(112) September 18, 2012

Bulletin ISSN: 2078–5178 of the public purchasing AnnouncerNº38(112) September 18, 2012 Announcements of conducting procurement procedures � � � � � � � � � 2 Announcements of procurement procedures results � � � � � � � � � � � � 30 Urgently for publication � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 72 Bulletin No�38(112) September 18, 2012 19215 Annoucements of conducting Lviv Municipal Enterprise “Lvivelektrotrans” 2 Sakharova St., 79012 Lviv procurement procedures Chykh Yevhen Yuriiovych tel./fax: (032) 237–77–79; 19212 e–mail: [email protected] Regional Municipal Enterprise Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: “Base of Special Medical Supply” www.tender.me.gov.ua 83/2 Kirova Ave., 49054 Dnipropetrovsk Website which contains additional information on procurement: Babchenko Kateryna Ihorivna, Kartavtsev Rostyslav Leonidovych www.city–adm.lviv.ua tel.: (056) 749–68–84; Procurement subject: code 34.10.3 – buses and trolleybuses (trolleybus tel./fax: (056) 749–66–51; “Skoda” 14 Tr or analog (used)), 20 lots e–mail: bazasmp–[email protected] Supply/execution: 1 Troleibusna St., 79053 Lviv, Trolleybus depot, Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: December 2012 – December 2013 www.tender.me.gov.ua Procurement procedure: open tender Procurement subject: code 24.42.1 – medications, 5 dnms. Obtaining of competitive bidding documents: at the customer’s address, office 17 Supply/execution: health care establishments of Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, 2012 Submission: at the customer’s address, office 17 Procurement procedure: open tender 19.10.2012 10:00 Obtaining of competitive bidding documents: at the customer’s address, office 309 Opening of tenders: at the customer’s address, office 14 Submission: at the customer’s address, office 309 19.10.2012 11:30 26.09.2012 09:00 Tender security: not required Opening of tenders: at the customer’s address, office 309 Additional information: For additional information, please, call at tel./fax: 26.09.2012 10:00 (032) 237–77–79. -

Населення України Population of Ukraine

Державна служба статистики України State Statistics Service of Ukraine ЧИСЕЛЬНІСТЬ НАЯВНОГО НАСЕЛЕННЯ УКРАЇНИ на 1 січня 2020 року NUMBER OF EXISTING POPULATION OF UKRAINE as of January 1, 2020 СТАТИСТИЧНИЙ ЗБІРНИК STATISTICAL PUBLICATION Київ Кyiv 2020 Державна служба статистики України State Statistics Service of Ukraine За редакцією Марії ТІМОНІНОЇ Edited by Mariia TIMONINA Відповідальний за випуск Олена ВИШНЕВСЬКА Responsible for edition is Olena VYSHNEVSKA У збірнику наведені статистичні дані щодо чисельності наявного населення в Україні та регіонах, містах, районах, селищах міського типу на 1 січня 2018–2020 років, кількість адміністративно-територіальних одиниць.Методологія розрахунку показників відповідає міжнародним та європейським стандартам, що забезпечує можливість їх порівняння з іншими країнами. Розрахований на широке коло користувачів. The compilation provides statistics on the number of existing population in Ukraine and regions, cities, districts, urban settlements as of January 1, 2018–2020, number of administrative and territorial units. The methodology for indicators compilation meets international and European standards, this ensures the possibility to compare them with other countries. Designed for a wide range of users. Державна служба статистики України State Statistics Service of Ukraine • адреса: вул. Шота Руставелі, 3, м. Київ, 01601, Україна address: 3, Shota Rustaveli str., Kyiv, 01601, Ukraine • телефони: (044) 284-31-28 telephone: (044) 284-31-28 • факс: (044) 235-37-39 fax: (044) 235-37-39 • електронна пошта: -

Zmiany Polskich Nazw Zawartych W „Urzędowym Wykazie Polskich Nazw Geograficznych Świata”

Zmiany polskich nazw zawartych w „Urzędowym wykazie polskich nazw geograficznych świata” opracował na podstawie protokołów z posiedzeń Komisji Standaryzacji Nazw Geograficznych poza Granicami Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej Maciej Zych Stan na 20 listopada 2019 roku Wykaz obejmuje zmiany w polskich nazwach obiektów geograficznych położonych poza granicami Polski względem nazewnictwa uwzględnionego w publikacji „Urzędowy wykaz polskich nazw geograficznych świata”, wydanej w grudniu 2013 roku http://ksng.gugik.gov.pl/pliki/urzedowy_wykaz_polskich_nazw_geograficznych_2013.pdf . Zmiany te zostały uchwalone przez Komisję Standaryzacji Nazw Geograficznych poza Granicami Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej na posiedzeniach od lutego 2014 roku. 1 Posiedzenia Komisji Standaryzacji Nazw Geograficznych poza Granicami Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej [83] posiedzenie odbyło się 26 lutego 2014 roku [84] posiedzenie odbyło się 23 kwietnia 2014 roku [85] posiedzenie odbyło się 24 września 2014 roku [86] posiedzenie odbyło się 19 listopada 2014 roku [87] posiedzenie odbyło się 4 marca 2015 roku [88] posiedzenie odbyło się 27 maja 2015 roku [89] posiedzenie odbyło się 23 września 2015 roku [90] posiedzenie odbyło się 4 listopada 2015 roku [91] posiedzenie odbyło się 2 grudnia 2015 roku [92] posiedzenie odbyło się 24 lutego 2016 roku [93] posiedzenie odbyło się 29 czerwca 2016 roku [94] posiedzenie odbyło się 19 października 2016 roku [95] posiedzenie odbyło się 23 listopada 2016 roku [96] posiedzenie odbyło się 1 lutego 2017 roku [97] posiedzenie odbyło się 29 marca 2017 roku -

ОГОЛОШЕННЯ Про Проведення Відкритих Торгів UA-2020-09-10-005344-C

ОГОЛОШЕННЯ про проведення відкритих торгів UA-2020-09-10-005344-c Найменування замовника: КОМУНАЛЬНЕ НЕКОМЕРЦІЙНЕ ПІДПРИЄМСТВО "ЦЕНТР ЕКСТРЕНОЇ МЕДИЧНОЇ ДОПОМОГИ ТА МЕДИЦИНИ КАТАСТРОФ" ЖИТОМИРСЬКОЇ ОБЛАСНОЇ РАДИ Purchasing body: KOMUNALNE NEKOMERTsIINE PIDPRIYeMSTVO "TsENTR EKSTRENOYi MEDIChNOYi DOPOMOGI TA MEDITsINI KATASTROF" ZhITOMIRSKOYi OBLASNOYi RADI Категорія замовника: Юридична особа, яка забезпечує потреби держави або територіальної громади Kind: Legal person providing the needs of the state or territorial community Ідентифікаційний код замовника в 38500095 ЄДР: National ID: 38500095 Місцезнаходження замовника: ВУЛИЦЯ ПОКРОВСЬКА, БУДИНОК 98-В, Житомир, Житомирська область, 10031, Україна Контактна особа замовника, Микитенко Ганна Михайлівна, уповноважена здійснювати зв’язок з [email protected], 380989720049 учасниками: Contact point: [email protected], 380989720049, Mykytenko Ganna Mykhaylivna Вид предмета закупівлі: Товари Main procurement category: goods Назва предмета закупівлі: код ДК 021:2015: 09130000-9 Нафта і дистиляти (Бензин А-92) Title of the subject of purchase: CPV 09130000-9 Petroleum and distillates (Petrol A-92) Код за Єдиним закупівельним ДК 021:2015:09130000-9: Нафта і дистиляти словником: CPV: DK 021:2015:09130000-9: Petroleum and distillates ЛОТ 1 — ЛОТ №1: код ДК 021:2015: 09130000-9 Нафта і дистиляти (Бензин А-92 для -пункту постійного базування бригад екстреної медичної допомоги Чуднівського району КНП «Центр екстреної медичної допомоги та медицини катастроф» Житомирської обласної ради; -пункту