Notes on the Giant Coot (Fulica Gigantea)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fulica Cornuta Bonaparte 1853 Nombre Común: Tagua Cornuda; Polla De Agua; Pato Negro; Gallina; Soca; Horned Coot (Inglés), Wari (Kunza)

FICHA DE ANTECEDENTES DE ESPECIE Id especie: Nombre Científico: Fulica cornuta Bonaparte 1853 Nombre Común: tagua cornuda; polla de agua; pato negro; gallina; soca; Horned Coot (inglés), Wari (kunza) Reino: Animalia Orden: Gruiformes Phyllum/Divis ión: Chordata Familia: Rallidae Clase: Aves Género: Fulica Sinonimia: Sin sinonimia Nota Taxonómica: Antecedentes Generales: ASPECTOS MORFOLÓGICOS: La tagua cornuda tiene el cuerpo rechoncho, de color uniformemente negruzco en ambos sexos, con la cabeza, cuello y hasta la espalda algo más oscura, y más gris apizarrada en la cara ventral del cuerpo. Los juveniles son en general más claros, sin negro en la cabeza y presentan una mancha blanca en el mentón y garganta. En el adulto el pico es fuerte y de color amarillo anaranjado, con una mancha negra en el culmen; en tanto que en los juveniles, el pico es negro verdoso con ligero tinte café. Las piernas en adultos y juveniles son de color verdoso, tirando al café con tinte gris oscuro a nivel de las articulaciones. Los dedos lobulados y provistos de poderosas uñas, son de gran tamaño, llegando a medir entre 20 y 30 cm de largo el dedo mayor. Los pies de los machos son apreciablemente más grandes que las de las hembras (Goodall et al. 1964, Araya et al. 1998, Martínez & González 2004, Jaramillo 2005). En los polluelos las piernas son negras, pero el pico es rosado con punta negra y amarilla y el cuerpo cubierto de un plumón fino y completamente negro, a excepción de una pequeña zona de plumillas blanquecinas en el mentón. El iris en el polluelo y en el ave juvenil es de color café, cambiando progresivamente mientras avanza a la adultez, hasta adquirir el característico color café anaranjado (Goodall et al. -

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

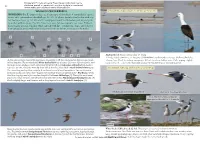

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

Neotropical News Neotropical News

COTINGA 1 Neotropical News Neotropical News Brazilian Merganser in Argentina: If the survey’s results reflect the true going, going … status of Mergus octosetaceus in Argentina then there is grave cause for concern — local An expedition (Pato Serrucho ’93) aimed extinction, as in neighbouring Paraguay, at discovering the current status of the seems inevitable. Brazilian Merganser Mergus octosetaceus in Misiones Province, northern Argentina, During the expedition a number of sub has just returned to the U.K. Mergus tropical forest sites were surveyed for birds octosetaceus is one of the world’s rarest — other threatened species recorded during species of wildfowl, with a population now this period included: Black-fronted Piping- estimated to be less than 250 individuals guan Pipile jacutinga, Vinaceous Amazon occurring in just three populations, one in Amazona vinacea, Helmeted Woodpecker northern Argentina, the other two in south- Dryocopus galeatus, White-bearded central Brazil. Antshrike Biata s nigropectus, and São Paulo Tyrannulet Phylloscartes paulistus. Three conservation biologists from the U.K. and three South American counter PHIL BENSTEAD parts surveyed c.450 km of white-water riv Beaver House, Norwich Road, Reepham, ers and streams using an inflatable boat. Norwich, NR10 4JN, U.K. Despite exhaustive searching only one bird was located in an area peripheral to the species’s historical stronghold. Former core Black-breasted Puffleg found: extant areas (and incidently those with the most but seriously threatened. protection) for this species appear to have been adversely affected by the the Urugua- The Black-breasted Puffleg Eriocnemis í dam, which in 1989 flooded c.80 km of the nigrivestis has been recorded from just two Río Urugua-í. -

Argentina and Chile, 2010

TRIP TO ARGENTINA & CHILE: 16/10 – 19/11/2010 From middle October till middle November 2010 we travelled in Argentina and Chile. Being two biologists, one of the goals of this travel was to enjoy nature. We have already looked a bit for mammals, mainly in Europe. During our trip, we kept an extra eye open for mammals and we tried to visit some good places to see some nice species. Hopefully this trip report can be useful for mammal watchers who want to visit the same areas in the future. Tim and Stefi This report includes 1. List of sightings for each location + pictures 2. Extra information on the locations 3. A note on transportation 4. Other animal sightings (birds, amphibians and reptiles) List of locations and mammal sightings A : NP Iguazu B : Esteros del Ibera C : Salta D : NP El Rey E : NP Calilegua F : Quebrada de Humahuaca G : NP Los Cardones + Cafayate H : Atacama I : Chiloé J : Peninsula Valdes Locations and English Names Info A Iguazu National Park Dates: 18 – 19 - 20 - 21 /10 1 Azara’s Agouti We saw two from the bus in the park on the Brazilian side, one close to the first viewpoint on the Brazilian side, two Dasyprocta azarae crossing the path on the Mapuco trail on the Argentinean side, one in the bushes near the Sheraton Hotel on the Argentinean side and one during the day crossing the road 101 at around 15pm on a cloudy day. 2 Coati We saw several on the Brazilian side while walking along the waterfall sightseeing path and several on the Nasua nasua Argentinean side as well on the waterfall circuits. -

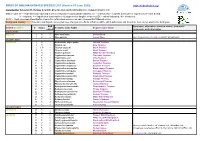

BIRDS of BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) Compiled By: Sebastian K

BIRDS OF BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) https://birdsofbolivia.org/ Compiled by: Sebastian K. Herzog, Scientific Director, Asociación Armonía ([email protected]) Status codes: R = residents known/expected to breed in Bolivia (includes partial migrants); (e) = endemic; NB = migrants not known or expected to breed in Bolivia; V = vagrants; H = hypothetical (observations not supported by tangible evidence); EX = extinct/extirpated; IN = introduced SACC = South American Classification Committee (http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm) Background shading = Scientific and English names that have changed since Birds of Bolivia (2016, 2019) publication and thus differ from names used in the field guide BoB Synonyms, alternative common names, taxonomic ORDER / FAMILY # Status Scientific name SACC English name SACC plate # comments, and other notes RHEIFORMES RHEIDAE 1 R 5 Rhea americana Greater Rhea 2 R 5 Rhea pennata Lesser Rhea Rhea tarapacensis , Puna Rhea (BirdLife International) TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE 3 R 1 Nothocercus nigrocapillus Hooded Tinamou 4 R 1 Tinamus tao Gray Tinamou 5 H, R 1 Tinamus osgoodi Black Tinamou 6 R 1 Tinamus major Great Tinamou 7 R 1 Tinamus guttatus White-throated Tinamou 8 R 1 Crypturellus cinereus Cinereous Tinamou 9 R 2 Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou 10 R 2 Crypturellus obsoletus Brown Tinamou 11 R 1 Crypturellus undulatus Undulated Tinamou 12 R 2 Crypturellus strigulosus Brazilian Tinamou 13 R 1 Crypturellus atrocapillus Black-capped Tinamou 14 R 2 Crypturellus variegatus -

Mobility, Subsistence, and Technological Strategies of Early Holocene Hunter-Gatherers in the Bolivian Altiplano

Quaternary International xxx (2017) 1e16 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint Mobility, subsistence, and technological strategies of early Holocene hunter-gatherers in the Bolivian Altiplano * Jose M. Capriles a, , Juan Albarracin-Jordan b, Douglas W. Bird a, Steven T. Goldstein c, Gabriela M. Jarpa d, Sergio Calla Maldonado e, Calogero M. Santoro f a Department of Anthropology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA b Instituto de Investigaciones Antropologicas y Arqueologicas, Universidad Mayor de San Andres, La Paz, Bolivia c Department of Archaeology, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Jena, Germany d Departamento de Antropología, Universidad de Tarapaca, Arica, Chile e Carrera de Arqueología, Universidad Mayor de San Andres, La Paz, Bolivia f Instituto de Alta Investigacion, Universidad de Tarapaca, Arica, Chile article info abstract Article history: The Altiplano constitutes the most extensive, high-elevation terrain in South America. Most archaeo- Received 15 January 2017 logical research on the earliest human occupation of this region in the Bolivian Andes derives from sites Received in revised form such as Viscachani where the emphasis has been on typological comparisons of projectile points, rather 20 August 2017 than on complete and radiometrically dated assemblages. In this paper, we present survey and exca- Accepted 30 August 2017 vation data from the Iroco region in the Central Altiplano of Bolivia to address questions related to the Available online xxx adaptive strategies engaged by Archaic Period highland foragers. Specifically, we focus on the nature of mobility, subsistence, and technological strategies, stemmed from principles in human behavioral Keywords: Andean Altiplano ecology. -

Argentina & Chili

ARGENTINA & CHILI 18 February – 30 March 2007 Raoul Beunen & Marije Louwsma www.avg-w.com Argentina The Northwest, San Pedro de Atacama in Chili & Esteros del Iberá In February and March 2007 we made a trip through north Argentina. We visited the sierras near Córdoba, Mendoza, the north-western part of Argentina, the adjacent Atacama Desert in Chilli, and Esteros del Iberá in the north-eastern part of Argentina. In Salta we hired a car for 12 days. All other travel was done by public transport. Travelling around in Argentina is very easy since there are many long-distance (overnight) busses between the different cities. Getting to national parks and other good places for bird watching might require some extra effort. Visiting San Pedro de Atacama is very easy since there are several busses a week from Salta to San Pedro. The bus ride across the high Andes (the highest pass is about 5200 m.) is really beautiful. Around San Pedro it is fairly easy to add some good species, like Giant & Horned Coot and Red-backed Sierra-finch to your list. The altiplano around San Pedro de Atacama, with the desert, Salinas, Valle de Luna, the high altitude lakes, and the world famous Tatio Geysers are definitely worth a visit. The weather February and March are not the best months to visit north-western Argentina. It is the end of the rainy season and usually very hot. We were lucky and had only little rain on the first day in Calilegua and mist at Cumbres del Obispo. In the lower parts the temperature was often high and bird activity was really low after 9 o’clock. -

North West Argentina Jujuy Birding Route 6 Days/ 5 Nights Tour, August 12Th to 17Th (+ Optional Tour Complement, August 18Th to 23Rd )

Rufous-throated Dipper - © Jorge La Grotteria Post “Ornithological Congress of the Americas 2017” Tour North West Argentina Jujuy birding route 6 days/ 5 nights tour, August 12th to 17th (+ optional tour complement, August 18th to 23rd ) WWW.BIRDINGBUENOSAIRES.COM Austral Yungas forest in Jujuy - © Marcelo Gavensky INTRODUCTION North-west Argentina is famous for its diversity of landscapes, wildlife and cultures. In a relatively small area it is possible to travel from the subtropical warm plains of the eastern lowlands to the high altitude cold Andean peaks, with a wide array of habitats and landscapes in between. This produces a very high bird diversity that goes from toucans and trogons to flamingoes and condors, just to mention a few iconic species. This trip comprises all major habitats of north-west Argentina, in a fairly new birding route that has been designed by us to take the best advantage of a relatively short period of time. The tour is divided in two stages: ● STAGE ONE: The Chaco lowlands and Austral Yungas forest (August 12th to 17th) Main targets: Andean Condor, King Vulture, Torrent Duck, White-rumped Hawk, Black-and-chestnut Eagle, Orange-breasted Falcon, Red-faced Guan, Black-legged Seriema, Red-legged Seriema, Golden- collared Macaw, Tucuman Parrot, Yungas Pygmy-Owl, Lyre-tailed Nightjar, Red-tailed Comet, Chaco Puffbird, Cream-backed Woodpecker, Crested Hornero, Spot-breasted Thornbird, Giant Antshrike, Stripe- backed Antbird, White-throated Antpitta, Olive-crowned Crescentchest, White-browed Tapaculo, Yungas Manakin, Rufous-throated Dipper, Many-colored Chaco-Finch, Rusty-browed Warbling-Finch, Yellow- striped Brush-Finch, Fulvous-headed Brush-Finch, Black-backed Grosbeak and more. -

Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World

Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World EUGENE M. McCARTHY OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World This page intentionally left blank Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World EUGENE M. MC CARTHY 3 2006 3 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugual Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2006 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data McCarthy, Eugene M. Handbook of avian hybrids of the world/Eugene M. McCarthy. p. cm. ISBN-13 978-0-19-518323-8 ISBN 0-19-518323-1 1. Birds—Hybridization. 2. Birds—Hybridization—Bibliography. I. Title. QL696.5.M33 2005 598′.01′2—dc22 2005010653 987654321 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper For Rebecca, Clara, and Margaret This page intentionally left blank For he who is acquainted with the paths of nature, will more readily observe her deviations; and vice versa, he who has learnt her deviations, will be able more accurately to describe her paths. -

Page 1 of 72 File://J:\BSP\LAC\Freshwater\06-15-99 Freshwater Pdf.Html 6/15/99 FRESHWATER BIODIVERSITY: Report of a Workshop On

Page 1 of 72 FRESHWATER BIODIVERSITY: Report of a workshop on the Conservation of Freshwater Biodiversity in Latin America and the Caribbean held in Santa Cruz, Bolivia, September 27-30, 1998 Implementers: World Wildlife Fund and Wetlands International Supported by: Biodiversity Support Program Editors: David Olson, Eric Dinerstein, Pablo Canevari, Ian Davidson, Gonzolo Castro, Virginia Morisset, Robin Abell, and Erick Toled WORLD WILDLIFE FUND (WWF), the largest privately-supported international conservation organization in the world, is dedicated to protecting the world's wildlife and wildlands. WWF directs its conservation efforts toward protecting and saving endangered species and addressing global threats. A conservation leader for more than 36 years, WWF has sponsored more than 2,000 projects in 116 countries and has more than one million members in the U.S. alone. The comprehensive global assessment of biological diversity recently completed by WWF scientists has identified more than 200 outstanding terrestrial, freshwater, and marine habitats. This new framework, called the Global 200, is helping to determine where conservation efforts are most needed, and, in the process, shaping the way governments, multilateral financial institutions, corporations, and conservation groups do their work. WETLANDS INTERNATIONAL (WI), created in 1995 through the integration of International Waterfowl and Wetlands Research Bureau, the Asian Wetland Bureau, and Wetlands for the Americas, is a world leader in conserving wetlands and wetland dependent species. WI's mission is to sustain and restore wetlands, their resources, and biodiversity for future generations through research, information exchange, and conservation activities worldwide. Programs are supported by a global network of more than 120 government agencies, national NGOs, foundations, development agencies, and private-sector groups. -

Northwest Argentina: Yungas, Chaco and High Andes Birding Tour

NORTHWEST ARGENTINA: YUNGAS, CHACO AND HIGH ANDES BIRDING TOUR 16 SEPTEMBER - 02 OCTOBER 2022 16 SEPTEMBER - 02 OCTOBER 2023 Rufous-throated Dipper is one of the most-wanted targets of the trip. Argentina is the second-largest country in South America and this birding trip offers the opportunity to travel across the northwestern section of this vast and picturesque land. We will go from lowland wetlands of Buenos Aires, through the dry Chaco shrublands and into the lush www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | ITINERARY Northwest Argentina Yungas cloudforest, before we climb in elevation through the dry Andean valleys and puna mountains to the high Andes in the Altiplano where we seemingly reach the roof of Argentina at 13,000 feet (3,900 meters). Our northwest Argentina trip can be considered one of the best birding trips in southern South America as it provides a unique set of birds found only in this part of the world which can be enjoyed by the most serious birder to those only setting foot on the continent for the first time. During this spectacular 17-day birding trip you may feast your eyes on some of the region’s most-wanted species such as Rufous-throated Dipper, Horned Coot, Diademed Sandpiper- Plover, Sandy Gallito, Red-faced Guan, Tucuman Mountain Finch, Moreno’s Ground Dove, Red-tailed Comet, Wedge-tailed Hillstar, the attractive Burrowing Parrot, White- throated Antpitta, Tucumán Amazon, Lyre-tailed Nightjar, Giant Antshrike, Black- legged Seriema and Black-bodied Woodpecker. Other more widespread yet classic neotropical species will include Andean Condor, Andean Goose, Torrent Duck and Southern Screamer, highly prized for those visiting South America for the first time. -

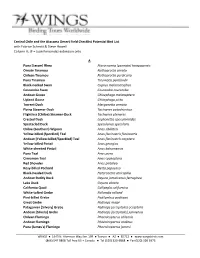

Central Chile and the Atacama Desert Field Checklist Potential Bird List with Fabrice Schmitt & Steve Howell Column A: JF = Juan Fernandez Extension Only

Central Chile and the Atacama Desert Field Checklist Potential Bird List with Fabrice Schmitt & Steve Howell Column A: JF = Juan Fernandez extension only A Puna [Lesser] Rhea Pterocnemia [pennata] tarapacensis Ornate Tinamou Nothoprocta ornata Chilean Tinamou Nothoprocta perdicaria Puna Tinamou Tinamotis pentlandii Black-necked Swan Cygnus melancoryphus Coscoroba Swan Coscoroba coscoroba Andean Goose Chloephaga melanoptera Upland Goose Chloephaga picta Torrent Duck Merganetta armata Flying Steamer-Duck Tachyeres patachonicus Flightless (Chiloe) Steamer-Duck Tachyeres pteneres Crested Duck Lophonetta specularioides Spectacled Duck Speculanus specularis Chiloe (Southern) Wigeon Anas sibilatrix Yellow-billed (Speckled) Teal Anas flavirostris flavirostris Andean [Yellow-billed/Speckled] Teal Anas flavirostris oxyptera Yellow-billed Pintail Anas georgica White-cheeked Pintail Anas bahamensis Puna Teal Anas puna Cinnamon Teal Anas cyanoptera Red Shoveler Anas platalea Rosy-billed Pochard Netta peposaca Black-headed Duck Heteronetta atricapilla Andean Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis ferruginea Lake Duck Oxyura vittata California Quail Callipepla californica White-tufted Grebe Rollandia rolland Pied-billed Grebe Podilymbus podiceps Great Grebe Podiceps major Patagonian [Silvery] Grebe Podiceps [occipitalis] occipitalis Andean [Silvery] Grebe Podiceps ]occipitalis] juninensis Chilean Flamingo Phoenicopterus chilensis Andean Flamingo Phoenicoparrus andinus Puna (James's) Flamingo Phoenicoparrus jamesi ________________________________________________________________________