Can 250+ Fusions Per Muon Be Achieved?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Controlled Nuclear Fusion

Controlled Nuclear Fusion HANNAH SILVER, SPENCER LUKE, PETER TING, ADAM BARRETT, TORY TILTON, GABE KARP, TIMOTHY BERWIND Nuclear Fusion Thermonuclear fusion is the process by which nuclei of low atomic weight such as hydrogen combine to form nuclei of higher atomic weight such as helium. two isotopes of hydrogen, deuterium (composed of a hydrogen nucleus containing one neutrons and one proton) and tritium (a hydrogen nucleus containing two neutrons and one proton), provide the most energetically favorable fusion reactants. in the fusion process, some of the mass of the original nuclei is lost and transformed to energy in the form of high-energy particles. energy from fusion reactions is the most basic form of energy in the universe; our sun and all other stars produce energy through thermonuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear Fusion Overview Two nuclei fuse together to form one larger nucleus Fusion occurs in the sun, supernovae explosion, and right after the big bang Occurs in the stars Initially, research failed Nuclear weapon research renewed interest The Science of Nuclear Fusion Fusion in stars is mostly of hydrogen (H1 & H2) Electrically charged hydrogen atoms repel each other. The heat from stars speeds up hydrogen atoms Nuclei move so fast, they push through the repulsive electric force Reaction creates radiant & thermal energy Controlled Fusion uses two main elements Deuterium is found in sea water and can be extracted using sea water Tritium can be made from lithium When the thermal energy output exceeds input, the equation is self-sustaining and called a thermonuclear reaction 1929 1939 1954 1976 1988 1993 2003 Prediction Quantitativ ZETA JET Project Japanese Princeton ITER using e=mc2, e theory Tokomak Generates that energy explaining 10 from fusion is fusion. -

Thermonuclear AB-Reactors for Aerospace

1 Article Micro Thermonuclear Reactor after Ct 9 18 06 AIAA-2006-8104 Micro -Thermonuclear AB-Reactors for Aerospace* Alexander Bolonkin C&R, 1310 Avenue R, #F-6, Brooklyn, NY 11229, USA T/F 718-339-4563, [email protected], [email protected], http://Bolonkin.narod.ru Abstract About fifty years ago, scientists conducted R&D of a thermonuclear reactor that promises a true revolution in the energy industry and, especially, in aerospace. Using such a reactor, aircraft could undertake flights of very long distance and for extended periods and that, of course, decreases a significant cost of aerial transportation, allowing the saving of ever-more expensive imported oil-based fuels. (As of mid-2006, the USA’s DoD has a program to make aircraft fuel from domestic natural gas sources.) The temperature and pressure required for any particular fuel to fuse is known as the Lawson criterion L. Lawson criterion relates to plasma production temperature, plasma density and time. The thermonuclear reaction is realised when L > 1014. There are two main methods of nuclear fusion: inertial confinement fusion (ICF) and magnetic confinement fusion (MCF). Existing thermonuclear reactors are very complex, expensive, large, and heavy. They cannot achieve the Lawson criterion. The author offers several innovations that he first suggested publicly early in 1983 for the AB multi- reflex engine, space propulsion, getting energy from plasma, etc. (see: A. Bolonkin, Non-Rocket Space Launch and Flight, Elsevier, London, 2006, Chapters 12, 3A). It is the micro-thermonuclear AB- Reactors. That is new micro-thermonuclear reactor with very small fuel pellet that uses plasma confinement generated by multi-reflection of laser beam or its own magnetic field. -

The Stellarator Program J. L, Johnson, Plasma Physics Laboratory, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey

The Stellarator Program J. L, Johnson, Plasma Physics Laboratory, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, U.S.A. (On loan from Westlnghouse Research and Development Center) G. Grieger, Max Planck Institut fur Plasmaphyslk, Garching bel Mun<:hen, West Germany D. J. Lees, U.K.A.E.A. Culham Laboratory, Abingdon, Oxfordshire, England M. S. Rablnovich, P. N. Lebedev Physics Institute, U.S.3.R. Academy of Sciences, Moscow, U.S.S.R. J. L. Shohet, Torsatron-Stellarator Laboratory, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin, U.S.A. and X. Uo, Plasma Physics Laboratory Kyoto University, Gokasho, Uj', Japan Abstract The woHlwide development of stellnrator research is reviewed briefly and informally. I OISCLAIWCH _— . vi'Tli^liW r.'r -?- A stellarator is a closed steady-state toroidal device for cer.flning a hot plasma In a magnetic field where the rotational transform Is produced externally, from torsion or colls outside the plasma. This concept was one of the first approaches proposed for obtaining a controlled thsrtnonuclear device. It was suggested and developed at Princeton in the 1950*s. Worldwide efforts were undertaken in the 1960's. The United States stellarator commitment became very small In the 19/0's, but recent progress, especially at Carchlng ;ind Kyoto, loeethar with «ome new insights for attacking hotii theoretics] Issues and engineering concerns have led to a renewed optimism and interest a:; we enter the lQRO's. The stellarator concept was borr In 1951. Legend has it that Lyman Spiczer, Professor of Astronomy at Princeton, read reports of a successful demonstration of controlled thermonuclear fusion by R. -

1 Looking Back at Half a Century of Fusion Research Association Euratom-CEA, Centre De

Looking Back at Half a Century of Fusion Research P. STOTT Association Euratom-CEA, Centre de Cadarache, 13108 Saint Paul lez Durance, France. This article gives a short overview of the origins of nuclear fusion and of its development as a potential source of terrestrial energy. 1 Introduction A hundred years ago, at the dawn of the twentieth century, physicists did not understand the source of the Sun‘s energy. Although classical physics had made major advances during the nineteenth century and many people thought that there was little of the physical sciences left to be discovered, they could not explain how the Sun could continue to radiate energy, apparently indefinitely. The law of energy conservation required that there must be an internal energy source equal to that radiated from the Sun‘s surface but the only substantial sources of energy known at that time were wood or coal. The mass of the Sun and the rate at which it radiated energy were known and it was easy to show that if the Sun had started off as a solid lump of coal it would have burnt out in a few thousand years. It was clear that this was much too shortœœthe Sun had to be older than the Earth and, although there was much controversy about the age of the Earth, it was clear that it had to be older than a few thousand years. The realization that the source of energy in the Sun and stars is due to nuclear fusion followed three main steps in the development of science. -

Eindhoven University of Technology BACHELOR the Effect of The

Eindhoven University of Technology BACHELOR The effect of the cathode radius on the neutron production in an IEC fusion device Wijnen, M. Award date: 2014 Link to publication Disclaimer This document contains a student thesis (bachelor's or master's), as authored by a student at Eindhoven University of Technology. Student theses are made available in the TU/e repository upon obtaining the required degree. The grade received is not published on the document as presented in the repository. The required complexity or quality of research of student theses may vary by program, and the required minimum study period may vary in duration. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain Bachelor Thesis The effect of the cathode radius on the neutron production in an IEC fusion device M.Wijnen Eindhoven University of Technology June 2014 Abstract While magnetic confinement fusion is reaching the next level with the develop- ment of ITER, many other methods to achieve fusion are studied in parallel. One of these methods is inertial electrostatic confinement (IEC) which utilizes electrostatic fields to create fusion. The Eindhoven University of Technology operates the TU/e Fusor, modelled after a Hirsch-Farnsworth fusor. -

Plasma Physics and Controlled Fusion Research During Half a Century Bo Lehnert

SE0100262 TRITA-A Report ISSN 1102-2051 VETENSKAP OCH ISRN KTH/ALF/--01/4--SE IONST KTH Plasma Physics and Controlled Fusion Research During Half a Century Bo Lehnert Research and Training programme on CONTROLLED THERMONUCLEAR FUSION AND PLASMA PHYSICS (Association EURATOM/NFR) FUSION PLASMA PHYSICS ALFV N LABORATORY ROYAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SE-100 44 STOCKHOLM SWEDEN PLEASE BE AWARE THAT ALL OF THE MISSING PAGES IN THIS DOCUMENT WERE ORIGINALLY BLANK TRITA-ALF-2001-04 ISRN KTH/ALF/--01/4--SE Plasma Physics and Controlled Fusion Research During Half a Century Bo Lehnert VETENSKAP OCH KONST Stockholm, June 2001 The Alfven Laboratory Division of Fusion Plasma Physics Royal Institute of Technology SE-100 44 Stockholm, Sweden (Association EURATOM/NFR) Printed by Alfven Laboratory Fusion Plasma Physics Division Royal Institute of Technology SE-100 44 Stockholm PLASMA PHYSICS AND CONTROLLED FUSION RESEARCH DURING HALF A CENTURY Bo Lehnert Alfven Laboratory, Royal Institute of Technology S-100 44 Stockholm, Sweden ABSTRACT A review is given on the historical development of research on plasma physics and controlled fusion. The potentialities are outlined for fusion of light atomic nuclei, with respect to the available energy resources and the environmental properties. Various approaches in the research on controlled fusion are further described, as well as the present state of investigation and future perspectives, being based on the use of a hot plasma in a fusion reactor. Special reference is given to the part of this work which has been conducted in Sweden, merely to identify its place within the general historical development. Considerable progress has been made in fusion research during the last decades. -

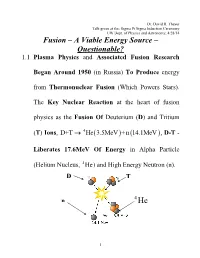

Fusion – a Viable Energy Source – Questionable? 1.1 Plasma Physics and Associated Fusion Research

Dr. David R. Thayer Talk given at the: Sigma Pi Sigma Induction Ceremony UW Dept. of Physics and Astronomy, 4/28/14 Fusion – A Viable Energy Source – Questionable? 1.1 Plasma Physics and Associated Fusion Research Began Around 1950 (in Russia) To Produce energy from Thermonuclear Fusion (Which Powers Stars). The Key Nuclear Reaction at the heart of fusion physics as the Fusion Of Deuterium (D) and Tritium (T) Ions, D+T 4 He 3.5MeV +n 14.1MeV , D-T - Liberates 17.6MeV Of Energy in Alpha Particle (Helium Nucleus, 4 He) and High Energy Neutron (n). D T n 1 1.2 Typical Conditions which produce fusion reaction Incorporate Plasma (High Temperature Gas of Electrons & Ions) Nuclear Ingredients at conditions: Density of n 1020 m 3, Temperature of T 10keV Objective: Overcome D-T Electrostatic Repulsion: D T Ignition (fusion sustained) Metric-Lawson Criteria: Density (ne )*Energy Confinement Time ( E ) = ne E Lawson Criteria 20 3 nme 10 E 1s 20 3 ne E 10 m s For D-T Fusion Te 10 keV or Approx. 100M degree C 2 1.3 Fusion Reactions Occur Naturally In Stars, due to tremendous Gravitation Forces, Fg m , which Radially Confine Plasma - Allow Sustained Fusion. However, Laboratory Fusion Plasmas must utilize Electromagnetic Forces, Fq E v B, typically Achieved Using: 1) Toroidal Magnetic Field Devices – Tokamak – Large Confining B Fields; or 2) Inertial Confinement Fusion – ICF – Devices numerous large Lasers Provide Implosion Pressure. 1) ITER – International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor 2) NIF – National Ignition Facility Lasers Hohlraum Contains -

Chapter 2: the Structure of The

SOLAR PHYSICS AND TERRESTRIAL EFFECTS 2+ Chapter 2 4= Chapter 2 The Structure of the Sun Astrophysicists classify the Sun as a star of average size, temperature, and brightness—a typical dwarf star just past middle age. It has a power output of about 1026 watts and is expected to continue producing energy at that rate for another 5 billion years. The Sun is said to have a diameter of 1.4 million kilometers, about 109 times the diameter of Earth, but this is a slightly misleading statement because the Sun has no true “surface.” There is nothing hard, or definite, about the solar disk that we see; in fact, the matter that makes up the apparent surface is so rarified that we would consider it to be a vacuum here on Earth. It is more accurate to think of the Sun’s boundary as extending far out into the solar system, well beyond Earth. In studying the structure of the Sun, solar physicists divide it into four domains: the interior, the surface atmospheres, the inner corona, and the outer corona. Section 1.—The Interior The Sun’s interior domain includes the core, the radiative layer, and the convective layer (Figure 2–1). The core is the source of the Sun’s energy, the site of thermonuclear fusion. At a temperature of about 15,000,000 K, matter is in the state known as a plasma: atomic nuclei (principally protons) and electrons moving at very high speeds. Under these conditions two protons can collide, overcome their electrical repulsion, and become cemented together by the strong nuclear force. -

Compact Fusion Reactors

Compact fusion reactors Tomas Lind´en Helsinki Institute of Physics 26.03.2015 Fusion research is currently to a large extent focused on tokamak (ITER) and inertial confinement (NIF) research. In addition to these large international or national efforts there are private companies performing fusion research using much smaller devices than ITER or NIF. The attempt to achieve fusion energy production through relatively small and compact devices compared to tokamaks decreases the costs and building time of the reactors and this has allowed some private companies to enter the field, like EMC2, General Fusion, Helion Energy, Lockheed Martin and LPP Fusion. Some of these companies are trying to demonstrate net energy production within the next few years. If they are successful their next step is to attempt to commercialize their technology. In this presentation an overview of compact fusion reactor concepts is given. CERN Colloquium 26th of March 2015 Tomas Lind´en (HIP) Compact fusion reactors 26.03.2015 1 / 37 Contents Contents 1 Introduction 2 Funding of fusion research 3 Basics of fusion 4 The Polywell reactor 5 Lockheed Martin CFR 6 Dense plasma focus 7 MTF 8 Other fusion concepts or companies 9 Summary Tomas Lind´en (HIP) Compact fusion reactors 26.03.2015 2 / 37 Introduction Introduction Climate disruption ! ! Pollution ! ! ! Extinctions Ecosystem Transformation Population growth and consumption There is no silver bullet to solve these issues, but energy production is "#$%&'$($#!)*&+%&+,+!*&!! central to many of these issues. -.$&'.$&$&/!0,1.&$'23+! Economically practical fusion power 4$(%!",55*6'!"2+'%1+!$&! could contribute significantly to meet +' '7%!89 !)%&',62! the future increased energy :&(*61.'$*&!(*6!;*<$#2!-.=%6+! production demands in a sustainable way. -

Extreme CPA Laser Pulses for Igniting Nuclear Fusion of Hydrogen with Boron-11 by Non-Thermal Pressures for Avoiding Ultrahigh Temperatures

Journal of Energy and Power Engineering 14 (2020) 156-177 doi: 10.17265/1934-8975/2020.05.003 D DAVID PUBLISHING Extreme CPA Laser Pulses for Igniting Nuclear Fusion of Hydrogen with Boron-11 by Non-thermal Pressures for Avoiding Ultrahigh Temperatures Heinrich Hora1, 2 1. Department of Theoretical Physics, University of New South Wales, Sydney 2052, Australia 2. HB11 Energy Holding Pty/Ltd, Freshwater 2096, Australia Abstract: Ten million times more compact energy than from burning carbon can be obtained from nuclear fusion reactions corresponding to equilibrium temperature reactions in the range above 100 million degrees. Following the energy gain in stars, one has to gain nuclear energy from slamming very light nuclei where however the extremely high temperatures above 100 million degrees are needed for the sufficient pressures at thermal equilibrium ignition. A radically new option works with non-thermal pressures of picosecond laser pulses at ultrahigh optical powers by nonlinear forces of ponderomotion. The nuclear fusion of hydrogen with the isotope 11 of boron produces primarily harmless helium and has no problems with dangerous radioactive waste and excludes any catastrophic melt-down as fission reactors, it has the potential to be of low costs and can supply the Earth for more than 10,000 years with electricity. Key words: Laser boron fusion, non-thermal ignition, plasma block acceleration, CPA pulses. 1. Introduction Lord Rutherford and Otto Hahn, to focus on nuclear energy for generators of electricity, based on the Nuclear fusion reactions are one possible option to milion times higher energy per reaction than chemical substitute burning carbon as energy source for energy from burning carbon. -

(TFR-1) Thermonuclear Fusion Reactor: Theoretical Construction and Application

(TFR-1) Thermonuclear Fusion Reactor: Theoretical Construction and Application Item Type Poster Authors Reyes-Mora, Joe Download date 05/10/2021 22:28:12 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/1986 (TFR-1) Thermonuclear Fusion Reactor: Theoretical Construction and Application Reyes - Mora, J. Mentor: Dr. Chawdhury, A. • The other way in which nuclear fusion has been achieved on the earth is in the device commonly Because of the increased height of the Coulomb energy barrier with increasing atomic number, it is generally Introduction TFR-1: Application of Theory Possible Results known as the hydrogen bomb. At the high temperatures produced in a fission reaction, nuclei of true that, at a given temperature, reactions involving the nuclei of hydrogen isotopes take place more readily isotopes of hydrogen undergo fusion with the liberation of energy. In these circumstances, the The TFR-1 would integrate a new system and theory to produce thermonuclear reactions which are based on The possible outcome estimated with the consulted information projects a possibility of a future completion • A Brief History Of Fusion: than do analogous reactions with heavier nuclei. In view of the great abundance of the lightest isotope of nuclear reactions are propagated so rapidly that the energy is released in an uncontrolled (or hydrogen, with mass number 1, it is natural to see if nuclear fusion reactions involving this isotope could be thermonuclear fusion explosive devices, originally created for defense purposes. The increment of yield and and mass production of the project. There are many calculations yet to make, but the theory points in a positive explosive) manner. -

The World's Simplest Fusion Reactor, and How to Make It Work

Revision Date: 1/05/2007 The World's Simplest Fusion Reactor, And How to Make It Work by Tom Ligon This article originally appeared in the December 1998 edition of Analog Science Fiction and Fact. Although edited slightly for reprints in Infinite Energy and for posting on fusor.net, it was intended for a fairly broad audience, especially high school science students. Fusor.net has my permission to post this article. Anyone else wishing to post it, ask my permission! This material is copyrighted. Tom Ligon A really distressing trend has been developing for some time among scientifically knowledgeable people I've met. A lot of you are growing quite pessimistic about the prospects for practical fusion power in general, and fusion-powered space travel in particular. The roots of this disillusionment are not hard to find. Fusion, for those of you who slept through high-school physics, is the process of squashing two atomic nuclei together to produce a new element. Many light-weight nuclei give off copious energy when this happens. In the Sun, hydrogen nuclei fuse (we pretend we know the mechanisms) to form helium. A tiny fraction of the original mass is converted to energy according to E = mc2. The process occurs deep in the Sun's core, at mind-boggling temperatures that cause the nuclei to move rapidly, where similarly mind-boggling pressure keeps the nuclei in close proximity, and sheer bulk prevents rapid heat escape. The physics community often calls these "thermonuclear reactions" 1 The World's Simplest Fusion Reactor because of the high temperatures driving them in the Sun, or triggering them in "hydrogen" bombs.