Rarnsar Convention DEE ESTUARY UNITED KINGDOM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessment of Childcare Sufficiency Flintshire County Council

Flintshire Childcare Sufficiency Assessment 2014 Assessment of Childcare Sufficiency Flintshire County Council Flintshire Childcare Sufficiency Assessment 2014 Contents INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................3 Statutory Duty 3 Methodology 4 CHILDREN AND FAMILIES IN FLINTSHIRE .......................................6 WORK AND FAMILY INCOMES ........................................................8 CHILDCARE: SUPPLY .................................................................. 10 CHILDCARE: DEMAND................................................................. 15 MARKET ANALYSIS ..................................................................... 21 Geographical Gaps 21 Type Gaps 24 Income Gaps 24 Specific Needs Gaps 26 Time Gaps 27 Language Gaps 27 Age Gaps 27 RECOMMENDATIONS .................................................................. 30 Page 2 Flintshire Childcare Sufficiency Assessment 2014 Introduction Statutory Duty The Childcare Act 2006 underpins the Welsh Assembly Government’s childcare strategy “Childcare is for Children” and enshrines in law: • Parents legitimate expectation of accessible high quality childcare for children and their families; and • Local Authorities responsibilities for providing information to parents and prospective parents to support their parenting role. The Childcare Act will achieve these aims through statutory duties that will build on Local Authorities’ existing roles and responsibilities. In Wales it will: • Place a duty giving Local Authorities -

Inspectors Report

The Planning Inspecto rate Report to the Secretary of Temple Quay House 2 The Square Temple Quay State for Transport Bristol BS1 6PN GTN 1371 8000 by A MEAD BSc(Hons) MRTPI MIQ an Inspector appointed by the Secretary of State for Transport Date: 28 March 2006 HARBOURS ACT 1964 Harbour Revision Orders Promoted by (A) Environment Agency (Wales) at the Dee Estuary & (B) Mostyn Docks Ltd at Mostyn Harbour Inquiry held on 29th – 30th November; 1st ,6th , 8th December 2005 File Ref: DPI/17/32 /LI A6835 2 Order A File Ref: DPI/17/32 /LI A6835 The Dee Estuary The Order would be made under Section 14 of the Harbours Act 1964 The promoter is the Environment Agency (EA) The Order would facilitate the implementation of the Port Marine Safety Code, modernise the Agency’s conservancy functions and enable ships dues to be collected [see paras 5.53 – 5.61 below]. The number of objectors at the close of the inquiry was four. Summary of Recommendation: To confirm subject to amendments as proposed by the EA. Order B File Ref: DPI/17/32 /LI A6835 Mostyn Harbour, Flintshire The Order would be made under Section 14 of the Harbours Act 1964 The promoter is Mostyn Docks Limited (Mostyn) The Order would facilitate the implementation of the Port Marine Safety Code and extend the powers of Mostyn in respect of Aids to Navigation, wreck removal and pilotage jurisdiction. The number of objectors at the close of the inquiry was six. Summary of Recommendation: To confirm, but only so far as pilotage is concerned. -

Pharmacies Providing Patient Sharps Boxes Exchange Service - As at April 2015

Pharmacies Providing Patient Sharps Boxes Exchange Service - as at April 2015 WEST Pharmacy Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 County Post Code S B Carr Ltd London Road Valley Anglesey LL65 3DP Rowlands Amlwch Primary Care Centre Parys Road Amlwch Anglesey LL68 9AB Rowlands 17 Castle Street Beumaris Anglesey LL58 8AP Rowlands Tyn-Y-Gongl Benllech Bay Anglesey LL74 8TG Rowlands Medical Hall Cemaes Bay Anglesey LL67 0HH Rowlands 62 Market Street Holyhead Anglesey LL65 1UN Rowlands Holyhead Road Llanfair PG Anglesey LL61 5UJ Rowlands 1 High Street Llangefni Anglesey LL77 7LT Rowlands Gormer Builders Yard Coronation Road Menai Bridge Anglesey LL59 5BD Boots Queens Square Dolgellau Gwynedd LL40 1AL Boots 277 - 279 High Street Bangor Gwynedd LL57 1PA Boots Ye Hen Orsaf Medical Centre Station Road Bethesda Gwynedd LL57 3NE Boots 1 - 3 Pool Lane Caernarfon Gwynedd LL55 2AL Penygroes Pharamcy 37 Water Street Penygroes Gwynedd LL54 6LR Mr Andrew Martin D Powys Davies 26 High Street Blaenau Ffestiniog Gwynedd LL41 3AA Rowlands High Street Abersoch Gwynedd LL53 7DY Rowlands 42 High Street Bala Gwynedd LL23 7AB Rowlands Bron Derw Glynne Road Bangor Gwynedd LL57 1AH Rowlands 29 Holyhead Road Bangor Gwynedd LL57 2EU Rowlands Cors Y Gedol high Street Barmouth Gwynedd LL42 1DP Rowlands 3 Eldon Row Dolgellau Gwynedd LL40 1PS Rowlands Medical Hall Harlech Gwynedd LL46 2YA Rowlands Compton House Llanberis Gwynedd LL55 4EU Rowlands Castle Street Penrhyndeudraeth Gwynedd LL48 6AL Rowlands 127 High Street Porthmadog Gwynedd LL49 9HA Rowlands The Old Post Office -

Order Details Site Details Flood

Flood Map - Slice A Order Details Order Number: 230192360_1_1 Customer Ref: 203021 National Grid Reference: 321290, 376070 Slice: A Site Area (Ha): 0.01 Search Buffer (m): 1000 Site Details Roadrunner Waste, Dee Bank Industrial Estate, BAGILLT, CH6 6HJ Tel: 0844 844 9952 Fax: 0844 844 9951 Web: www.envirocheck.co.uk A Landmark Information Group Service v50.0 10-Jan-2020 Page 3 of 5 For Borehole information please refer to the Borehole .csv file which accompanied this slice. A copy of the BGS Borehole Ordering Form is available to download from the Support section of www.envirocheck.co.uk. Borehole Map - Slice A Order Details Order Number: 230192360_1_1 Customer Ref: 203021 National Grid Reference: 321290, 376070 Slice: A Site Area (Ha): 0.01 Search Buffer (m): 1000 Site Details Roadrunner Waste, Dee Bank Industrial Estate, BAGILLT, CH6 6HJ Tel: 0844 844 9952 Fax: 0844 844 9951 Web: www.envirocheck.co.uk A Landmark Information Group Service v50.0 10-Jan-2020 Page 4 of 5 OS Water Network Map - Slice A Order Details Order Number: 230192360_1_1 Customer Ref: 203021 National Grid Reference: 321290, 376070 Slice: A Site Area (Ha): 0.01 Search Buffer (m): 1000 Site Details Roadrunner Waste, Dee Bank Industrial Estate, BAGILLT, CH6 6HJ Tel: 0844 844 9952 Fax: 0844 844 9951 Web: www.envirocheck.co.uk A Landmark Information Group Service v50.0 10-Jan-2020 Page 5 of 5 Envirocheck ® Report: Datasheet Order Details: Order Number: 230192360_1_1 Customer Reference: 203021 National Grid Reference: 321290, 376070 Slice: A Site Area (Ha): 0.01 Search Buffer -

BAGILLT COMMUNITY NEWSLETTER Chairman's

BAGILLT COMMUNITY NEWSLETTER Issue Number 3 July 2008 Chairman's Comments Welcome to the third Bagillt Community newsletter, which is the first since I was elected Chairman in May 2008, a position I will hold for 12 months. I hope you will enjoy reading the content. This is my second term as Chairman of the Council having been a Councillor since 1990. I was born in Bagillt and have always lived in the community. I work locally in Flint and have for a number of years served as a governor of Ysgol Merllyn. Following positive feedback from local residents, the Community Council has decided to continue producing a further edition. We will continue to share information on services, other organisations and update contacts following the recent County and Community Council elections. In this edition we will also welcome our new Community Policeman, Chris Byron and update you on his work within the community as well as informing the public about summer play schemes and the arrangements for the Community Caretaker. Since the last newsletter a new notice board has been provided at the Community Centre in the High Street. Organisations wishing to use this facility or either of the other two notice boards at the car park, High Street and Riverbank, can contact the key holders listed on the respective boards. Unfortunately the Council have had to discontinue the provision of hanging baskets in the High Street for 2008, as it has not been possible to arrange appropriate watering arrangements. It is intended to re- introduce this facility in 2009 with the purchase of a water bowser and hopefully recruit volunteers from the village to undertake the regular watering needed in the summer months. -

INDEX to LEAD MINING RECORDS at FLINTSHIRE RECORD OFFICE This Index Is Not Comprehensive but Will Act As a Guide to Our Holdings

INDEX TO LEAD MINING RECORDS AT FLINTSHIRE RECORD OFFICE This index is not comprehensive but will act as a guide to our holdings. The records can only be viewed at Flintshire Record Office. Please make a note of all reference numbers. LOCATION DESCRIPTION DATE REF. NO. Aberduna Lease. 1872 D/KK/1016 Aberduna Report. 1884 D/DM/448/59 Aberdune Share certificates. 1840 D/KK/1553 Abergele Leases. 1771-1790 D/PG/6-7 Abergele Lease. 1738 D/HE/229 Abergele See also Tyddyn Morgan. Afon Goch Mine Lease. 1819 D/DM/1206/1 Anglesey Leases of lead & copper mines in Llandonna & Llanwenllwyfo. 1759-1788 D/PG/1-2 Anglesey Lease & agreement for mines in Llanwenllwyfo. 1763-1764 D/KK/326-7 Ash Tree Work Agreement. 1765 D/PG/11 Ash Tree Work Agreement. 1755 D/MT/105 Barber's Work Takenote. 1729 D/MT/99 Belgrave Plan & sections of Bryn-yr-orsedd, Belgrave & Craig gochmines 19th c D/HM/297-9 Belgrave Section. 1986 D/HM/51 Belgrave Mine, Llanarmon License to assign lease & notice req. performance of lease conditions. 1877-1887 D/GR/393-394 Billins Mine, Halkyn Demand for arrears of royalties & sale poster re plant. 1866 D/GR/578-579 Black Mountain Memo re lease of Black Mountain mine. 19th c D/M/5221 Blaen-y-Nant Mine Co Plan of ground at Pwlle'r Neuad, Llanarmon. 1843 D/GR/1752 Blaen-y-Nant, Llanarmon Letter re takenote. 1871 D/GR/441 Bodelwyddan Abandonment plans of Bodelwyddan lead mine. 1857 AB/44-5 Bodelwyddan Letter re progress of work. -

LDP-KPD-HRA2 Dep HRA Screen Rep Oct 2020

LDP-KPD-HRA2 HABITATS REGULATIONS ASSESSMENT Flintshire Local Development Plan Screening Report OCTOBER 2020 CONTACTS ALEX ELLIS Arcadis. Arcadis Cymru House, St. Mellons Business Park, Fortran Road, Cardiff, CF3 0EY Arcadis Consulting (UK) Limited is a private limited company registered in England & Wales (registered number 02212959). Registered Office at Arcadis House, 34 York Way, London, N1 9AB, UK. Part of the Arcadis Group of Companies along with other entities in the UK. Copyright © 2015 Arcadis. All rights reserved. arcadis.com Error! No text of specified style in document. Screening Report Liz Turley Author Joseph Evans Checker David Hourd Approver Report No 10010431-ARC-XX-XX-RP-TC-0005-01 Date OCTOBER 2020 VERSION CONTROL Version Date Author Changes September 01 LT First issue 2019 25 September 02 LT Final issue 2019 27 October 03 AE Amended to incorporate changes to the LDP 2020 This report dated 27 October 2020 has been prepared for Flintshire County Council (the “Client”) in accordance with the terms and conditions of appointment dated 07 June 2017(the “Appointment”) between the Client and Arcadis Consulting (UK) Limited (“Arcadis”) for the purposes specified in the Appointment. For avoidance of doubt, no other person(s) may use or rely upon this report or its contents, and Arcadis accepts no responsibility for any such use or reliance thereon by any other third party. CONTENTS VERSION CONTROL ............................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... -

Wirral Landscape Character Assessment 2019 A

Wirral Metropolitan Borough Council Wirral Landscape Character Assessment Final report Prepared by LUC October 2019 Wirral Metropolitan Borough Council Wirral Landscape Character Assessment Version Status Prepared Checked Approved Date 1. Draft Final Report A Knight K Davies K Davies 07.10.2019 K Davies 2. Final Report A Knight K Davies K Davies 30.10.2019 Bristol Land Use Consultants Ltd Landscape Design Edinburgh Registered in England Strategic Planning & Assessment Glasgow Registered number 2549296 Development Planning Lancaster Registered office: Urban Design & Masterplanning London 250 Waterloo Road Environmental Impact Assessment Manchester London SE1 8RD Landscape Planning & Assessment Landscape Management landuse.co.uk 100% recycled paper Ecology Historic Environment GIS & Visualisation Contents Wirral Landscape Character Assessment October 2019 Contents 1c: Eastham Estuarine Edge 60 Chapter 1 Introduction and Landscape Context 4 Chapter 7 Structure of this report 4 LCT 2: River Floodplains 67 Background and purpose of the Landscape Character Assessment 4 2a: The Birket River Floodplain 68 The role of Landscape Character Assessment 5 Wirral in context 5 2b: The Fender River Floodplain 75 Policy context 6 Relationship to published landscape studies 9 Chapter 8 LCT 3: Sandstone Hills 82 Chapter 2 Methodology for the Landscape 3a: Bidston Sandstone Hills 83 Character Assessment 13 3b: Thurstaston and Greasby Sandstone Hills 90 3c: Irby and Pensby Sandstone Hills 98 Approach 13 3d: Heswall Dales Sandstone Hills 105 Process of assessment -

New Park Road, Aston Park, Deeside. CH5 1XD £190,000 MS9964

New Park Road, Aston Park, Deeside. CH5 1XD £190,000 MS9964 DESCRIPTION: A bright and airy detached bungalow with a beautifully sunny garden. The property has been improved by the present owner and unusually has a garage large enough for two cars. The accommodation briefly comprises:- entrance hall, lounge with feature fire place, spacious fitted kitchen/breakfast room, conservatory, two bedrooms, utility room/ third bedroom and wet room. Gas heating and double glazing. Paved driveway for parking. The garage has light and power connected and electrically operated door. Lovely gardens which are established. VIEWING RECOMMENDED ANGELA WHITFIELD FNAEA – RES IDENT PARTNER Viewing by arrangement through Shotton Office 33 Chester Road West, Shotton, Deeside, Flintshire, CH5 1BY Tel: 01244 814182 Opening hours 9.00am-5.30pm Monday – Friday 9.00am – 4.00pm Saturday DIRECTIONS: Turn right out of the Shotton office and proceed under the railway bridge to the traffic lights and turn right into Shotton lane and proceed until the lane narrows and bear left into the one way system and continue until turning right into Courtland Drive and turn first left into Summerdale and first right into New Park Road where the property will be seen on the right hand side. LOCATION: Situated in a popular residential area and convenient for the A55 expressway allowing access to Chester, Liverpool and the North Wales Coast. HEATING: Gas heating with radiators. ENTRANCE HALL: Radiator, laminate floor and built in cloaks cupboard. LOUNGE: 16' x 11' 9" (4.88m x 3.58m) Radiator and double glazed window. Living flame gas fire in attractive fire surround. -

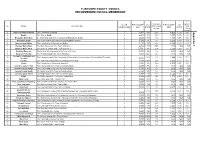

Appendix 2 of Draft Proposals

FLINTSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL RECOMMENDED COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP % % variance variance No. OF ELECTORATE 2018 ELECTORATE 2023 No. NAME DESCRIPTION from County from COUNCILLORS 2018 RATIO 2023 RATIO average County average 1 Argoed and New Brighton The Community of Argoed 2 4,564 2,282 26% 4,856 2,428 29% 3 Appendix 2 Bagillt The Town of Bagillt 2 3,201 1,601 -12% 3,269 1,635 -13% 3 Broughton North East the North East ward of the Community of Broughton & Bretton 1 1,693 1,693 -6% 1,706 1,706 -10% 4 Broughton South The South ward of the Community of Broughton & Bretton 2 3,350 1,675 -7% 3,359 1,680 -11% 5 Brynford and Halkyn The Communities of Brynford and Halkyn 2 3,173 1,587 -12% 3,239 1,620 -14% 6 Buckley: Bistre East The Bistre East ward of the Town of Buckley 2 3,262 1,631 -10% N/A N/A N/A 7 Buckley: Bistre West The Bistre West ward of the Town of Buckley 2 3,230 1,615 -11% 3,566 1,783 -5% 8 Buckley: Mountain The Buckley Mountain ward of the Town of Buckley 1 2,049 2,049 13% N/A N/A N/A 9 Buckley: Pentrobin The Pentrobin ward of the Town of Buckley 2 4,063 2,032 12% N/A N/A N/A Caergwrle, Llanfynydd and 10 The Caergwrle ward of the Community of Hope and the Communities of Llanfynydd and Treuddyn 2,028 12% 4,180 2,090 11% Treuddyn 2 4,055 11 Caerwys The Town of Caerwys and the Community of Ysceifiog 1 2,018 2,018 12% 2,176 2,176 15% 12 Cilcain The Commuities of Cilcain and Nannerch 1 1,526 1,526 -16% 1,547 1,547 -18% 13 Connah's Quay Central The Central ward of the Town of Connah's Quay 2 3,509 1,755 -3% N/A N/A N/A 14 Connah's Quay: Golftyn -

Gronant Street a Development of 2 and 3 Bedroom Affordable Homes, Available to Buy Through Homebuy

Opening Doors – Enhancing Lives Gronant Street A development of 2 and 3 bedroom affordable homes, available to buy through Homebuy. Contemporary homes designed for modern, busy lifestyles. 0800 183 5757 www.clwydalyn.co.uk Gronant Street Specification A development of two and three bedroom homes for sale All properties are built to Code for Sustainable Homes level 3+. The Code aims to protect the environment by providing through Homebuy. guidance on the construction of high performance homes built with sustainability in mind. Benefits to our customers include energy and water efficiency which is achieved via the specification of the homes. Gronant Street is a development of affordable two and three bedroom homes available to buy under the Homebuy Scheme (funded by the Welsh Government, these homes are offered for disposal on Homebuy Exterior Heating Car Parking terms under their tenure neutral scheme). Ideally suited for couples • Traditional construction • PVC double glazed window’s throughout • Designated car parking space and families, the new contemporary homes have been built to a high • External brick and rear canopy • Energy efficient gas central heating quality standard and complete with environmental design features; • Front and rear gardens landscaped system with radiators, thermostatic valves General providing you with the benefits of an energy-efficient home, with • Divisional timber fencing included and programmer Quality chrome furniture fitted to affordable running costs. • Pathways and small patio area as standard • Insulated lofts to ensure high heat retention • panelled white doors • Rotary dryer and rainwater storage butt • Cavity wall insulation to add thermal and Architrave and skirting The new development is owned by Clwyd Alyn Housing Association, sound insulation • fitted throughout part of the Pennaf Housing Group and is supported by Denbighshire Electrical • Mechanically vented bathroom and kitchen County Council and the Welsh Government. -

Ice Skating and Learning to Skate at Deeside Leisure Centre Sunday

Learn to Skate Sunday Tel: 01352 704200 Skate UK Saturday Grade 7 - 9am - 9.30am Skate UK Grade 8 - 9am - 9.30am Grade 7 - 9am - 9.30am Bronze - 9am - 9.30am Grade 8 - 9am - 9.30am Silver - 9am - 9.30am Bronze - 9am - 9.30am Dance Bronze, Silver & Gold - 9am - 9.30am Silver - 9am - 9.30am Adults - 9am - 9.30am Grade 1 - 9.30am - 10am Mini’s - 9am - 9.30am Grade 2 - 9.30am - 10am (7 & Under) Grade 3 - 9.30am - 10am Grade 1 - 8.30am - 9am Grade 4 - 9.30am - 10am for our next two courses only, Grade 5 - 9.30am - 10am 16/03/19 - 20/04/19 and Grade 6 - 9.30am - 10am 27/04/19 - 01/06/19 Public Skate 10am - 12pm included Grade 2 - 9.30am - 10am FREE Grade 3 - 9.30am - 10am Grade 4 - 9.30am - 10am Ice Skating and Grade 5 - 9.30am - 10am Learning to Skate at Grade 6 - 9.30am - 10am Deeside Leisure Centre Public Skate 10am - 12pm included FREE Ice Skating Class start dates lessons over ® Buckley Leisure Centre Deeside Leisure Centre Jade Jones Mold Leisure Centre (6 week classes) Mill Lane, Buckley, Chester Road West, Pavilion Flint Wrexham Road, Mold, a 6 week course Our 6 week Week Commencing Flintshire, CH7 3HB Queensferry, Deeside, Earl Street, Flint, Flintshire, CH7 1HT is just £41.40 11/03/19 & 22/04/19. learn to skate course 01352 704290 Flintshire, CH5 1SA Flintshire, CH6 5ER 01352 704330 is just £41.40 01352 704200 01352 704301 Check website for any changes to schedule Bookings office 01352 704200 Bookings office 01352 704200 www.aura.cymru Like Follow us www.aura.wales Ice Rink Price List Ice Rink Time Table Learn to Skate Tel: 01352