Gender Representation of Athletes in Finnish and Swedish Tabloids a Quantitative and Qualitative Content Analysis of Athens 2004 and Turin 2006 Olympics Coverage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doping in Sport, the Rules on “Missed Tests”, “Non- Analytical Finding” Cases and the Legal Implications by Gregory Ioannidis*

Doping in Sport, the Rules on “Missed Tests”, “Non- Analytical Finding” Cases and the Legal Implications by Gregory Ioannidis* Much discussion has been generated with the introduction of a new of one or more anti-doping rule violations”. These anti-doping viola- rule to combat the use of performance enhancing substances and tions may incur in situations where the athlete did not use perform- methods in sport. This discussion has been initiated and subsequent- ance enhancing substances, but simply, where he “missed”, “failed” ly became an integral part of the sporting public opinion, as a result and/or “evaded” the test. For the purposes of analysing these rules, we of the application of this rule on high profile professional athletes, would call these specific cases “non-analytical finding” cases. such as the Greek sprinters Kenteris and Thanou. 1 The reason for the examination of the IAAF’s rule, concentrates on Before, however, an analysis of the application of this rule can be the fact that it is attracting intense criticism, in relation to its applica- produced, it is first of all necessary to explain and define the opera- tion on anti-doping violations. In addition, this regulation in ques- tion of the rule and perhaps attempt to discover the reasons for its cre- tion has been associated with high profile cases, and has also become ation. the source of a unique form of questioning. A series of questions arise The article would concentrate on the IAAF’s [International out of its construction, interpretation and application in practice. Association of Athletics Federations] rule on missed tests and critical- These questions cannot be answered without a further examination ly analyse its definition and application, particularly at the charging of the factual issues that surround the application of this regulation. -

Detailed List of Performances in the Six Selected Events

Detailed list of performances in the six selected events 100 metres women 100 metres men 400 metres women 400 metres men Result Result Result Result Year Athlete Country Year Athlete Country Year Athlete Country Year Athlete Country (sec) (sec) (sec) (sec) 1928 Elizabeth Robinson USA 12.2 1896 Tom Burke USA 12.0 1964 Betty Cuthbert AUS 52.0 1896 Tom Burke USA 54.2 Stanislawa 1900 Frank Jarvis USA 11.0 1968 Colette Besson FRA 52.0 1900 Maxey Long USA 49.4 1932 POL 11.9 Walasiewicz 1904 Archie Hahn USA 11.0 1972 Monika Zehrt GDR 51.08 1904 Harry Hillman USA 49.2 1936 Helen Stephens USA 11.5 1906 Archie Hahn USA 11.2 1976 Irena Szewinska POL 49.29 1908 Wyndham Halswelle GBR 50.0 Fanny Blankers- 1908 Reggie Walker SAF 10.8 1980 Marita Koch GDR 48.88 1912 Charles Reidpath USA 48.2 1948 NED 11.9 Koen 1912 Ralph Craig USA 10.8 Valerie Brisco- 1920 Bevil Rudd SAF 49.6 1984 USA 48.83 1952 Marjorie Jackson AUS 11.5 Hooks 1920 Charles Paddock USA 10.8 1924 Eric Liddell GBR 47.6 1956 Betty Cuthbert AUS 11.5 1988 Olga Bryzgina URS 48.65 1924 Harold Abrahams GBR 10.6 1928 Raymond Barbuti USA 47.8 1960 Wilma Rudolph USA 11.0 1992 Marie-José Pérec FRA 48.83 1928 Percy Williams CAN 10.8 1932 Bill Carr USA 46.2 1964 Wyomia Tyus USA 11.4 1996 Marie-José Pérec FRA 48.25 1932 Eddie Tolan USA 10.3 1936 Archie Williams USA 46.5 1968 Wyomia Tyus USA 11.0 2000 Cathy Freeman AUS 49.11 1936 Jesse Owens USA 10.3 1948 Arthur Wint JAM 46.2 1972 Renate Stecher GDR 11.07 Tonique Williams- 1948 Harrison Dillard USA 10.3 1952 George Rhoden JAM 45.9 2004 BAH 49.41 1976 -

Olympic Quiz

Eurosport. All sports. All emotions. OLYMPIC QUIZ Are you a Games expert? Test your friends with this bumper set of questions from Gavin Fuller Our quizmaster Gavin Fuller has compiled all the tools you need for a huge Olympics quiz to test the knowledge of family and friends. So gather everyone around — at home, at your workplace or in the pub. In this pack you will find complete question lists spread out over 20 categories, team answer sheets and solutions. It’s the perfect way to whet everyone’s appetite for the Games. When the Games start, Eurosport will be covering its 12th edition of the Olympics, with more than 100 hours in 3D on Sky 3D and Virgin Media. British Eurosport is available in HD on Sky 410 and Virgin Media 522, and online or on your mobile via eurosportplayer.co.uk. If you love athletics, cycling, swimming and tennis, there’s no better place to watch than Eurosport. £ British Eurosport is the home of cycling with more coverage than any other channel, including all three Grand Tours, major Spring Classics and the road and track World Championships. £ Eurosport recently showcased its commitment to athletics with coverage of the European and World Junior Championships. £ British Eurosport will show more than 1,200 hours of blockbuster tennis in 2012, including the Australian, French and US Open championships and the Davis Cup. Quiz sheet 1 Eurosport. All sports. All emotions. Olympic history (1) Famous Olympians 1 Who was president of the IOC from 1896 to 1925, and 1 Which current Premier League footballer was top scorer -

2018 World Indoor Championships Statistics – Women’S 60M - by K Ken Nakamura Summary Page

2018 World Indoor Championships Statistics – Women’s 60m - by K Ken Nakamura Summary Page: All time performance list at the World Indoor Championships Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 6.95 Gail Devers USA 1 Toronto 1993 2 2 6.96 Katerina Thanou GRE 1 Maebashi 1999 3 3 6.97 Irina Privalova RUS 2 Toronto 1993 3 3 6.97 Merlene Ottey JAM 1 Barcelona 1995 5 6.99 Katerina Thanou 1sf1 Maebashi 1999 Slowest winning time: 7.08 by Nelli Cooman (NED) in 1987 & Gail Devers (USA) in 2004; Silke Gladisch won the 1985 World Indoor Games in even slower time of 7.20 Margin of Victory (in final) Difference Winning Time Name Nat Venue Year Max 0.13 6.97 Merlene Ottey JAM Barcelona 1995 Min 0.001 7.008 Me’Lisa Barber USA Moskva 2006 Fastest time in each round at World Indoor Championships Round Time Name Nat Heat/Semi Venue Year Final 6.95 Gail Devers USA 1 Toronto 1993 Semi -final 6.99 Katerina Thanou GRE 1sf1 Maebashi 1999 First round 7.01 Katerina Thanou GRE 1h1 Maebashi 1999 Fastest non-qualifier for the final Time Position Name Nat Venue Year 7.12 4sf2 Liliana Allen MEX Maebashi 1999 Best Marks for Places in the World Indoor Championships Pos Time Name Nat Venue Year 1 6.95 Gail Devers USA Toronto 1993 2 6.97 Irina Privalova RUS Toronto 1993 3 7.07 Gail Devers USA Maebashi (semi 1) 1999 Philomina Mensah CAN Maebashi 1999 Multiple Gold Medalists: Veronica Campbell-Brown (JAM): 2010, 2012 Gail Devers (USA): 1993, 1997, 2004 Nelli Cooman (NED): 1987, 1989 GBR All-Comer’s List Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue DMY 1 1 6.98 -

2018 European Championships Statistics – Women’S 100M by K Ken Nakamura

2018 European Championships Statistics – Women’s 100m by K Ken Nakamura Summary Page All time performance list at the European Championships Performance Performer Time Wind Name Nat Pos Venue Yea 1 1 10.73 2.0 Christine Arron FRA 1 Budape st 1998 2 10.81 1.3 Christine Arron 1sf1 Budapest 1998 3 2 10.83 2.0 Irina Privalova RUS 2 Budapest 1998 4 3 10.87 2.0 Ekaterini Thanou GRE 3 Budapest 1998 5 4 10.89 1.8 Katrin Krabbe GDR 1 Split 1990 6 5 10.90 -0.2 Dafne Schippers NED 1 Amsterdam 2016 7 6 10.91 0.8 Marlies Göhr GDR 1 Stuttgart 1986 Margin of Victory Difference Winning time Wind Name (winner) Nat Venue Year Max 0.30 10.90 -0.2 Dafne Schippers NED Amsterdam 2016 Min 0.01 11.10 0.6 Verena Sailer GER Barcelona 2010 Best Marks for Places in the European Championships Pos Time Wind Name Nat Venue Year 1 10.73 2.0 Christine Arron FRA Budapest 1998 2 10.83 2.0 Irina Privalova RUS Budapest 1998 3 10.87 2.0 Ekaterini Thanou GRE Budapest 1998 4 10.92 2.0 Zhanna Pintusevich-Block UKR Budapest 1998 Fastest non-qualifier for the final Time Wind Position Name Nat Venue Year 11.21 1.3 5sf1 Oksana Ekk RUS Budapest 1998 Multiple Gold Medalists: Marlies Göhr (GDR): 1978, 1982, 1986 Dafne Schippers (NED) 2014, 2016 Multiple Medals by athletes from a single nation Nation Year Gold Silver Bronze FRA 2010 Veronique Mang Myriam Soumare RUS 2006 Yekaterina Grigoryeva Irina Khabarova GDR 1990 Katrin Krabbe Silke Gladisch-Möller Kerstin Behrendt GDR 1982 Marlies Göhr Barbel Wöckel FRG 1971 Ingrid Mickler-Becker Elfgard Schittenhelm POL 1966 Klobukowska Irena Szewinska -

2014 European Championships Statistics – Women's 100M

2014 European Championships Statistics – Women’s 100m by K Ken Nakamura All time performance list at the European Championships Performance Performer Time Wind Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 10.73 2.0 Christine Arron FRA 1 Budapest 1998 2 10.81 1.3 Christine Arron 1sf1 Budapest 1998 3 2 10.83 2.0 Irina Privalova RUS 2 Budapest 1998 4 3 10.87 2.0 Ekaterini Thanou GRE 3 Budapest 1998 5 4 10.89 1.8 Katrin Krabbe GDR 1 Split 1990 6 5 10.91 0.8 Marlies Göhr GDR 1 Stuttgart 1986 7 10.92 0.9 Ekaterini Thanou 1sf2 Budapest 1998 7 6 10.92 2.0 Zhanna Pintusevich -Block UKR 4 Budapest 1998 9 10.98 1.2 Marlies Göhr 1sf2 Stuttgart 1986 10 11.00 1.3 Zhanna Pintusevich -Block 2sf1 Budapest 1998 11 11.01 -0.5 Marlies Göhr 1 Athinai 1982 11 11.01 0.9 Zhanna Pintusevich -Block 1h2 Helsinki 1994 13 11.02 0.6 Irina Privalova 1 Helsinki 1994 13 11.02 0.9 Irina Privalova 2sf2 Budapest 1998 15 7 11.04 0.8 Anelia Nuneva BUL 2 Stuttgart 1986 15 11.04 0.6 Ekaterini Thanou 1h4 Budapest 1998 17 8 11.05 1.2 Silke Gladisch -Möller GDR 2sf2 Stuttgart 1986 17 11.05 0.3 Ekaterini Thanou 1sf2 München 2002 19 11.06 -0.1 Marlies Göhr 1h2 Stuttgart 1986 19 11.06 -0.8 Zhanna Pintusevich -Block 1h1 Budapest 1998 19 9 11.06 1.8 Kim Gevaert BEL 1 Göteborg 2006 22 10 11.06 1.7 Ivet Lalova BUL 1h2 Helsinki 2012 22 11.07 0.0 Katrin Krabbe 1h1 Split 1990 22 11 11.07 2.0 Melanie Paschke GER 5 Budapest 1998 25 11.07 0.3 Ekaterini Thanou 1h4 München 2002 25 11.08 1.2 Anelia Nuneva 3sf2 Stuttga rt 1986 27 12 11.08 0.8 Nelli Cooman NED 3 Stuttgart 1986 28 11.09 0.8 Silke Gladisch -Möller -

2013 World Championships Statistics

2013 World Championships Statistics - Women’s 100m by K Ken Nakamura The records to look for in Moskva: 1) Can Belssing Okagbare become the first African to win a world championships medal at W100m? 2) Can Shelly Ann Fraser-Pryce or Carmelita Jeter join Marion Jones as a two-time winner? 3) The fastest W100m on Russian soil (10.82) as well as in Moskva (10.82) are likely to be broken. All time performance list at the World Championships Performance Performer Time Wind Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 10.70 -0.1 Marion Jones USA 1 Sevilla 1999 2 2 10.73 0.1 Shelly-Ann Fraser JAM 1 Berlin 2009 3 3 10.75 0.1 Kerron Stewart JAM 2 Berlin 2009 4 10.76 0.3 Marion Jones 1qf4 Sevilla 1999 5 4 10.79 -0.1 Inger Miller USA 2 Sevilla 1999 5 10.79 -0.1 Shelly-Ann Fraser 1sf1 Berlin 2009 7 10.81 0.1 Inger Miller 1sf1 Sevilla 1999 8 5 10.811 0.3 Gail Devers USA 1 Stuttgart 1993 8 5 10.812 0.3 Marlene Ottey JAM 2 Stuttgart 1993 8 5 10.82 0.3 Zhanna Pintusevich UKR 1 Edmonton 2001 11 10.83 0.4 Marion Jones 1 Athinai 1997 11 8 10.83 0.1 Katerina Thanou GRE 2sf1 Sevilla 1999 11 10.83 -0.1 Marion Jones 1sf2 Sevilla 1999 11 8 10.83 -0.1 Carmelina Jeter USA 1sf2 Berlin 2009 15 10 10.84 1.4 Gwen Torrence 1sf1 Göteborg 1995 15 10.84 -0.1 Katerina Thanou GRE 3 Sevilla 1999 15 10.84 -0.1 Kerron Stewart 2sf1 Berlin 2009 18 10.85 1.4 Marlene Ottey 2sf1 Göteborg 1995 18 10.85 0.9 Gwen Torrence USA 1 Göteborg 1995 18 10.85 0.4 Zhanna Pintusevich 2 Athinai 1997 21 10.86 -0.3 Katerina Thanou 1qf1 Sevilla 1999 21 10.86 0.7 Inger Miller 1qf2 Sevilla 1999 23 10.87 -0.3 Marlene -

Results 100 Metres Women Final Heats

Organiser: Under The Auspices: Filothei Sports Club Filothei (GRE) - Mon, 14 June 2021 Results Municipal Stadium "Stelios Kiriakidis" 100 Metres Women Final Heats Start time : 18:30 Records Perf Wind Competitor Yob Nat Venue Date world 10.49 +0.0 Florence GRIFFITH-JOYNER 1959 USA Indianapolis (University Stadium), IN 16.07.1988 Area - Europe 10.73 +2.0 Christine ARRON 1973 FRA Budapest (Népstadion) 19.08.1998 World Leading 2021 10.63 +1.3 Shelly-Ann FRASER-PRYCE 1986 JAM Kingston (JAM) 05.06.2021 Meeting Record 11.18 +1.9 Natalia POHREBNIAK 1988 UKR Filothei (GRE) 08.06.2016 National Record (GRE) 10.83 +0.1 Ekaterini THANOU 1975 GRE Sevilla (ESP) 22.08.1999 Pos Athlete Year of Birth Nat / Team Mark Wind HPL Notes Score 1 SPANOUDAKI-CHATZIRIGA, RAFALIA 1994 GRE / Greece 11.59 -0.9 3 (1) 2 TSIMANOUSKAYA, KRYSTSINA 1996 BLR / Belarus 11.79 -0.9 3 (2) 3 PAPAIOANNOU, RAMONA-ANNA 1989 CYP / Cyprus 11.80 -0.9 3 (3) 4 GATOU, MARIA 1989 GRE / Greece 11.82 -0.9 3 (4) 5 DALAKA, KATERINA 1992 GRE / Greece 11.90 -1.3 2 (1) 6 ANASTASIOU, ARTEMIS-MELINA 2000 GRE / Greece 11.94 -1.3 2 (2) 7 TIRNANIC, MILANA 1994 SRB / Serbia 11.96 -0.9 3 (5) 8 MICHAILIDOU, STYLIANI-ALEXANDRA 1999 GRE / Greece 12.09 -1.3 2 (3) 9 PODHORODETSKA, YEVA 2001 UKR / Ukraine 12.18 -1.3 2 (4) 10 ROUMELIOTI, FOTINI 2001 GRE / Greece 12.42 -1.3 2 (5) 11 MPAIRAMI, EFTHIMIA-KONSTANTINA 1998 GRE / Greece 12.50 -1.0 1 (1) 12 KRIMITSA, LYDIA 2002 GRE / Greece 12.56 -1.0 1 (2) 13 KOLOVOU, VASILIKI-ARISTEA 2004 GRE / Greece 12.73 -1.0 1 (3) 14 VASILOPOULOU, PINELOPI 2002 GRE / Greece 12.87 -

2009 Outdoor Handbook

IAAF Outdoor Handbook 2009 IAAF 2009 OUTDOOR HANDBOOK International Association of Athletics Federations 17 rue Princesse Florestine Postal: BP 359 - MC 98007 Monaco Cedex Tel: +377 93 10 88 88 Fax: +377 93 15 95 15 Internet: http://www.iaaf.org Printed in Monaco by Multiprint Copyright IAAF 2009 IAAF Outdoor Handbook 2009 CONTENTS / SOMMAIRE IAAF PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE/ Message du Président de l'IAAF............................. IV IAAF COUNCIL / Conseil de l'IAAF ............................................................................... VI IAAF COMPETITION COMMISSION / Commission des Compétitions de l'IAAF...... 1 2009 OUTDOOR CALENDAR / Calendrier 2009 en plein air....................................... 2 WORLD ATHLETICS TOUR MEETINGS RULES 2009.................................................. 9 GOLDEN LEAGUE RULES 2009 .................................................................................... 20 IAAF WORLD ATHLETICS FINAL RULES 2009............................................................ 22 CODES OF CONDUCT IN INTERNATIONAL PERMIT MEETINGS............................... 25 RÈGLEMENTS DES MEETINGS DU TOUR MONDIAL DE L’ATHLÉTISME IAAF 2009.. 32 RÈGLEMENTS DE LA GOLDEN LEAGUE 2009 ........................................................... 44 FINALE MONDIALE D’ATHLÉTISME DE L’IAAF 2009.................................................. 46 CODE DE CONDUITE POUR LES MEETINGS INTERNATIONAUX À PERMIS .......... 49 IAAF GOLDEN LEAGUE & SUPER GRAND PRIX / Golden League & Super Grand Prix de l'IAAF Schedule / Calendrier.................................................................................................... -

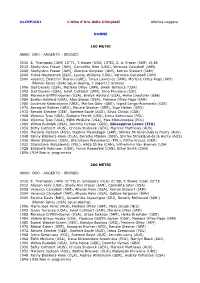

Argento - Bronzo

OLIMPIADI L'Albo d'Oro delle Olimpiadi Atletica Leggera DONNE 100 METRI ANNO ORO - ARGENTO - BRONZO 2016 E. Thompson (JAM) 10”71, T. Bowie (USA) 10”83, S. A. Fraser (JAM) 10,86 2012 Shelly-Ann Fraser (JAM), Carmelita Jeter (USA), Veronica Campbell (JAM) 2008 Shelly-Ann Fraser (JAM), Sherone Simpson (JAM), Kerron Stewart (JAM) 2004 Yuliva Nesterenko (BLR), Lauryn Williams (USA), Veronica Campbell (JAM) 2000 vacante, Ekaterini Thanou (GRE), Tanya Lawrence (JAM), Merlene Ottey-Page (JAM) (Marion Jones (USA) squal.doping, 2 argenti 1 bronzo) 1996 Gail Devers (USA), Merlene Ottey (JAM), Gwen Torrence (USA) 1992 Gail Devers (USA), Juliet Cuthbert (JAM), Irina Privalova (CSI) 1988 Florence Griffith-Joyner (USA), Evelyn Ashford (USA), Heike Drechsler (GEE) 1984 Evelyn Ashford (USA), Alice Brown (USA), Merlene Ottey-Page (JAM) 1980 Lyudmila Kondratyeva (URS), Marlies Göhr (GEE), Ingrid Lange-Auerswald (GEE) 1976 Annegret Richter (GEO), Renate Stecher (GEE), Inge Helten (GEO) 1972 Renate Stecher (GEE), Raelene Boyle (AUS), Silvia Chivás (CUB) 1968 Wyomia Tyus (USA), Barbara Ferrell (USA), Irena Szewinska (POL) 1964 Wyomia Tyus (USA), Edith McGuire (USA), Ewa Klobukowska (POL) 1960 Wilma Rudolph (USA), Dorothy Hyman (GBR), Giuseppina Leone (ITA) 1956 Betty Cuthbert (AUS), Christa Stubnick (GER), Marlene Matthews (AUS) 1952 Marjorie Jackson (AUS), Daphne Hasenjäger (SAF), Shirley Strickland-de la Hunty (AUS) 1948 Fanny Blankers-Koen (OLA), Dorothy Manley (GBR), Shirley Strickland-de la Hunty (AUS) 1936 Helen Stephens (USA), Stanislawa Walasiewicz (POL), Käthe Krauss (GER) 1932 Stanislawa Walasiewicz (POL), Hilda Strike (CAN), Wilhelmina Van Bremen (USA 1928 Elizabeth Robinson (USA), Fanny Rosenfeld (CAN), Ethel Smith (CAN) 1896-1924 Non in programma 200 METRI ANNO ORO - ARGENTO - BRONZO 2016 E. -

![[Physics.Pop-Ph] 3 Oct 1997](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2755/physics-pop-ph-3-oct-1997-5402755.webp)

[Physics.Pop-Ph] 3 Oct 1997

It’s a Wrap! Reviewing the 1997 Outdoor Season J. R. Mureika Department of Computer Science University of Southern California Los Angeles, CA 90089-2520 Throughout the summer, I’ve written articles highlighting this year’s 100m performances, and ranking them according to their wind-corrected values. Now that the fall months draw to a close, and the temperature drops to a nippy 15 celsius at night (well, for some of us), it seems only natural to wrap up the year with a rundown of the 1997 rankings. Of course, it wouldn’t be exciting to just give the official rankings, so I will also present the wind-corrected rankings, and will offer comparison to the adjusted value of the athlete’s best 100m performance of 1996. Mind you, this won’t necessarily be the best wind-corrected performance, but it can offer an insight into how an athlete has progressed over the course of a year. As a quick refresher, a 100m time tw assisted by a wind w (the wind speed) can be corrected to an equivalent time t0 as run with no wind (w = 0 m/s), 2 w × tw t0 ≈ 1.03 − 0.03 × 1 − × tw . (1) 100 " # This comes about because approximately 3% of the athlete’s effort is spent fighting atmospheric drag. A tail-wind implicitly boosts a race time, hile a head-wind can take away a sprinter’s chance at a possible World Record. (as an interesting aside: this also says that it takes more energy to run into a head-wind than you get from a tail-wind assistance. -

Newsletter B10/N.26 1 June 2010

Newsletter B10/n.26 1 June 2010 1 26 July - 1 August Barcelona 2010 thrills with cinema commercial bcn2010.org Manolo Martinez (left), Naroa Agirre and Jackson Quiñonez (below) star in the Barcelona 2010 commercial On 19 May, from dawn to dusk, seven of the main Spanish athletes participated in a commercial for the European Athletics Championships Barcelona 2010. The Montjuïc Olympic Stadium was the stage for this long day, which had more to do with cinema than athletics. In the commercial, designed by the agency Villarosàs (the successful bidder in the tender organised), Naroa Agirre, Concha Montaner, Jackson Quiñónez, Reyes Estévez, Juan Carlos Higuero, Ángel David Rodríguez and Manolo Martínez illustrate, with carefully composed shots, that what seems easy from a distance is not when viewed close up. This is the commercial’s message. Athletics is not an easy sport and not everyone dares to Pole Vault or Shot Put. More than 150 volunteers participated in the shooting as extras. For a few hours the Olympic Stadium became a film set, and the popular band “Love of Lesbian” played the commercial’s soundtrack, called “Incondicional”. The commercial will be broadcast on several TV channels during the month prior to the start of the European Athletics Championships Barcelona 2010, from 21 June. The commercial will be the main feature of the final Barcelona 2010 promotional campaign. This television promotion campaign will be added to the more traditional campaigns used previously, in order to reach as many fans as possible. Buy your event pass now! Visit servicaixa.com For more information consult our website: www.bcn2010.org Newsletter B10/n.26 1 June 2010 2 26 July - 1 August 76-year-old Championships bcn2010.org As we do not have a poster of the men´s European Athletics Championships of 1938 (that was the only event where men and women competed separately), in this historical section we present the available graphical elements that were used to promote the previous 19 championships to date.