8 August 2007 P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Echo of Delphi: the Pythian Games Ancient and Modern Steven Armstrong, F.R.C., M.A

An Echo of Delphi: The Pythian Games Ancient and Modern Steven Armstrong, F.R.C., M.A. erhaps less well known than today’s to Northern India, and from Rus’ to Egypt, Olympics, the Pythian Games at was that of kaloi k’agathoi, the Beautiful and PDelphi, named after the slain Python the Good, certainly part of the tradition of Delphi and the Prophetesses, were a mani of Apollo. festation of the “the beautiful and the good,” a Essentially, since the Gods loved that hallmark of the Hellenistic spirituality which which was Good—and for the Athenians comes from the Mystery Schools. in particular, what was good was beautiful The Olympic Games, now held every —this maxim summed up Hellenic piety. It two years in alternating summer and winter was no great leap then to wish to present to versions, were the first and the best known the Gods every four years the best of what of the ancient Greek religious and cultural human beings could offer—in the arts, festivals known as the Pan-Hellenic Games. and in athletics. When these were coupled In all, there were four major celebrations, together with their religious rites, the three which followed one another in succession. lifted up the human body, soul, and spirit, That is the reason for the four year cycle of and through the microcosm of humanity, the Olympics, observed since the restoration the whole cosmos, to be Divinized. The of the Olympics in 1859. teachings of the Mystery Schools were played out on the fields and in the theaters of the games. -

2004 Olympic Trials Results

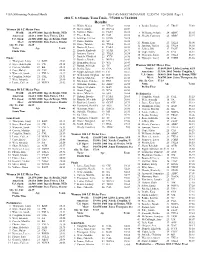

USA Swimming-National Meets Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 12:55 PM 1/26/2005 Page 1 2004 U. S. Olympic Team Trials - 7/7/2004 to 7/14/2004 Results 13 Walsh, Mason 19 VTAC 26.08 8 Benko, Lindsay 27 TROJ 55.69 Women 50 LC Meter Free 15 Silver, Emily 18 NOVA 26.09 World: 24.13W 2000 Inge de Bruijn, NED 16 Vollmer, Dana 16 FAST 26.12 9 Williams, Stefanie 24 ABSC 55.95 American: 24.63A 2000 Dara Torres, USA 17 Price, Keiko 25 CAL 26.16 10 Shealy, Courtney 26 ABSC 55.97 18 Jennings, Emilee 15 KING 26.18 U.S. Open: 24.50O 2000 Inge de Bruijn, NED 19 Radke, Katrina 33 SC 26.22 Meet: 24.90M 2000 Dara Torres, Stanfor 11 Phenix, Erin 23 TXLA 56.00 20 Stone, Tammie 28 TXLA 26.23 Oly. Tr. Cut: 26.39 12 Jamison, Tanica 22 TXLA 56.02 21 Boutwell, Lacey 21 PASA 26.29 Name Age Team 13 Jeffrey, Rhi 17 FAST 56.09 22 Harada, Kimberly 23 STAR 26.33 Finals Time 14 Cope, Haley 25 CAJ 56.11 23 Jamison, Tanica 22 TXLA 26.34 15 Wanezek, Sarah 21 TXLA 56.19 24 Daniels, Elizabeth 22 JCCS 26.36 Finals 16 Nymeyer, Lacey 18 FORD 56.56 25 Boncher, Brooke 21 NOVA 26.42 1 Thompson, Jenny 31 BAD 25.02 26 Hernandez, Sarah 19 WA 26.43 2 Joyce, Kara Lynn 18 CW 25.11 27 Bastak, Ashleigh 22 TC 26.47 Women 100 LC Meter Free 3 Correia, Maritza 22 BA 25.15 28 Denby, Kara 18 CSA 26.50 World: 53.66W 2004 Libby Lenton, AUS 4 Cope, Haley 25 CAJ 25.22 29 Ripple Johnston, Shell 23 ES 26.51 American: 53.99A 2002 Natalie Coughlin, U 5 Wanezek, Sarah 21 TXLA 25.27 29 Medendorp, Meghan 22 IST 26.51 U.S. -

U10 Activities - Dribbling for Possession Objective: to Improve Dribbling and Shielding Technique

U10 Activities - Dribbling for Possession Objective: To improve dribbling and shielding technique Technical Warm up Organization Coaching Pts. Technical Box: Keep the ball close All players dribbling in a defined space. Use all surfaces of the foot Players should use all surfaces of their feet. o Inside/outside Coach: Prompt players to work on change of o Sole direction, scissors, fake left/go right, step over o Laces and turn, pull back, half-turn, sole of the foot Keep your head up and use rolls when he claps, “change”, “turn”, etc. peripheral vision Version 2: Walk around and put pressure on Change of direction and burst the players. of speed Version 3: Players will try to knock each Be creative – try something other’s soccer balls out of the grid while new maintaining possession of their own. Time: 15 minutes Small Sided Game Organization Coaching Pts. Steal-Shield: Body sideways on to opponent Pair up the players with one ball. One Use arm to protect and know player starts with the ball and at coach’s where defender is going command, his/her partner tries to steal the Knees bent ball away. The player that ends with the Turn as defender attacks or ball gets a point. If the ball goes out of reaches for the ball bounds, one of the players must get it back in play very quickly. Coach: Show proper shielding technique during the demonstration. Fix technical shielding errors throughout the activity to assure that the group is doing it properly. Time: 15 minutes Exp. Small Sided Game Organization Coaching Pts. -

Douglas Sanders's Article

5th Asian Law Institute Conference National University of Singapore, May 22 and 23, 2008 377 - and the unnatural afterlife of British colonialism Professor Douglas Sanders Chulalongkorn University, Mahidol University sanders_gwb @ yahoo.ca, May 6, 2008 Article 377 of the Indian Penal Code of 1860 made “carnal intercourse against the order of nature” an offence. This provision, or something very close to it, is presently in force in all former British colonies in Asia with the exception of Hong Kong. Even the article number, 377, is repeated in the current laws in force in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei - as if it were a special brand name, all of its own. Sri Lanka, Seychelles and Papua New Guinea have the key wording from article 377, but different section numbers. Parallel wording appears in the criminal laws of many of the former colonies in Africa. Surprisingly, viewing the matter from Asia, the 377 wording was never part of the criminal law in Britain. 377 is an amazingly successful law – if we judge it by its geographical spread and its longevity. Soon it will be 150 years old. How was it formulated? How did it come to apply in Asia? What is its role today? 2 First, we have to look back to the reign of Henry VIII and the break of the English church from Rome. I BACK TO BUGGERY British criminal laws covering homosexual acts began in 1534. Legislation in the reign of Henry VIII, prohibited …the detestable and abominable Vice of Buggery committed with mankind or beast. -

Impact Report 2018-2019 Nysi Impact Report 2018-2019

IMPACT REPORT 2018-2019 NYSI IMPACT REPORT 2018-2019 Building multiple pathways SSI Optimising talent pool National Team Linear NSA Age University (Pure Ascent) Groups International & Overseas Schools JC, Poly, ITE Clubs SSP DSA Mainstream ActiveSG Secondary & Private Schools Academies Learn to Primary JSA Play Schools Non-Linear (Mixed Descent, Ascent) In its third year of existence, NYSI continued to seamless youth athlete and coach development focus resources on targeted sports and youth pathways. athletes for better national outcomes. In view of our small talent pool, NYSI strove to To provide better support for youth athletes support, identify and transfer high-performing outside of SSP and improve the youth sports youth athletes to reduce attrition and optimise ecosystem, NYSI plugged gaps by building talent. NYSI IMPACT REPORT 2018-2019 NYSI IMPACT BY NUMBERS 3,064 NSAs Sessions 1,575 253 1,236 Sessions Sessions Sessions 6,348 Youth Athletes 266 5,582 500 Youth Athletes Youth Athletes Youth Athletes 548 164 211 300 10 Coaches 164 industry 211 coaches attended NYSI tested over 300 NYSI Sport Science staff professionals attended the 3rd Youth Coaching youth athletes for the TOP have published 10 papers the 3rd Youth Athlete Conference Athlete Programme since 2016 150 Development Conference Parents NYSI IMPACT REPORT 2018-2019 Singapore Sport NYSI IMPACT ON Institute ECOSYSTEM National Team NSA Age Groups University TALENT OPTIMISATION JC, Poly, ITE DSA Mainstream Secondary Schools ActiveSG & CAMPAIGN SUPPORT TALENT IDENTIFICATION Private Academies Junior Sports Academy Learn to Primary Play Schools ATHLETE DEVELOPMENT PATHWAYS NYSI IMPACT REPORT 2018-2019 CAMPAIGN SUPPORT Campaigns NYSI has SUPPORTED NYSI has supported the Singapore National Olympic Council, National Sports Associations, the Ministry of Education, and the Singapore University Sports Council in their overseas campaigns. -

2020-08-19-XI-Physical Education-1.Pdf

PHYSICAL EDUCATION CLASS 11 Chapter 2: Olympic Value Education P. 34-36 A. Objective Questions/ Multiple-Choice Questions 1 mark I. Give one word answers. 1. State the Olympic motto in three Latin words. Ans. Citius, Altius, Fortius 2. Name the place where the first Modern Olympics was organised. Ans. Athens in Greece 3. Name the tradition originated from ancient Greece Olympics to ensure the safe travel of the players and spectators in the games. Ans. Olympic Truce 4. Who designed the Olympic Symbol? Ans. Pierre de Coubertin 5. Name the first president of the International Olympic Committee. Ans. Demetrios Vikelas 6. Name the country which hosted the Olympics in 2016. Ans. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 7. Who was the first President of the Indian Olympic Association? Ans. Sir Dorabji Tata 8. Name the place where the first Winter Olympics was organised. Ans. Chamonix, France II. Fill in the blanks. 1. The International Olympic Committee, the governing authority of the Modern Olympic Games is based in ____________. Ans. Laussane, Switzerland 2. The first Summer Youth Olympics were hosted by __________in 2010. Ans. Singapore 3. The Olympic flag was first hoisted in 1920 at _________. Ans. Antwerp Games, Belgium 4. Three runners called ________ travelled to all Greek city-states to spread the message of Olympic truce during the Ancient Olympic Games. Ans. Spondophoroi 5. The Olympic games were abolished in 394 CE by Roman emperor ________. Ans. Theodosius I 6. ___________ are the parallel games to the Olympics. Ans. Paralympics 7. ________ was an African–American athlete whose honour was refused by Adolf Hitler. -

The Date of the First Pythiad-Again Alden A

MOSSHAMMER, ALDEN A., The Date of the First Pythiad - Again , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 23:1 (1982:Spring) p.15 The Date of the First Pythiad-Again Alden A. Mosshammer OST HISTORIANS have long agreed that the first in the regular M series of Pythian festivals celebrated every four years at Del phi took place in 58211. Now H. C. Bennett and more re cently S. G. Miller have argued that we should instead follow Pausa nias in dating the first Pythiad to 586/5, because the Pindaric scho liasts, they maintain, reckon Pythiads from that year. 1 The debate is an old one, but it has important implications for our understanding of the sequence of events at the time of the First Sacred War. Bennett and Miller have rightly criticized the excessive claims that have been made for some of the evidence; and Miller, in particular, has offered some important new insights into the problem. The argument in favor of 58211 nevertheless remains the stronger case. It needs to be presented once again, both to take these new objections into account and to elucidate the tradition that has given rise to the debate. I. The Problem According to the Parian Marble, our earliest evidence (264/3), the Amphictyons celebrated a victory against Cirrha by dedicating a por tion of the spoils as prizes for a chrematitic festival celebrated in 59110, and again the games became stephani tic in 582/1. 2 Pausanias 1 H. C. BENNETT, "On the Systemization of Scholia Dates for Pindar's Pythian Odes," HSCP 62 (1957) 61-78; STEPHEN G. -

How Well Do You Know the Olympic Games?

HOW WELL DO YOU KNOW THE OLYMPIC GAMES? This manual, which is intended for the general public, provides an introduction to the Olympic Movement and the Olympic HOW WELL DO YOU KNOW Games. The brochure is made up of 15 sections, each one introduced THE OLYMPIC by a question. Each section provides basic information and some additional GAMES? details about the topics that it covers. WHERE DID THE OLYMPIC GAMES BEGIN? The Olympic Games The Ancient Greeks held athletic collectively as the Panhellenic Games. began in Greece. competitions in Olympia in the Peloponnese. The first existing The ancient Olympic Games lasted for more than 1000 written records of these events years! Over this long period, the programme evolved date back to 776 BC. and the sports included in it varied considerably. After enjoying significant popularity, the Games gradually What was special about these Games? They took began to lose their prestige. place every four years, and were dedicated to Zeus, the king of the gods. Their deathblow was dealt by the Roman emperor Theodosius I. A convert to Christianity, he would not They were open only to free men of Greek citizen- tolerate pagan events within his empire, and abolished ship, which meant that men from other countries, them in 393 AD. women and slaves were unable to take part. Married women were not allowed to watch the Games, Information about the ancient Games can be discovered although the spectators did include girls. by examining a training scene painted on a vase, the sculpture of an athlete, or a few verses composed to A few months before the competitions began, a sacred the glory of an athletic winner. -

The Legacy of the Games of the New Emerging Forces' and Indonesia's

The International Journal of the History of Sport ISSN: 0952-3367 (Print) 1743-9035 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fhsp20 The Legacy of the Games of the New Emerging Forces and Indonesia’s Relationship with the International Olympic Committee Friederike Trotier To cite this article: Friederike Trotier (2017): The Legacy of the Games of the New Emerging Forces and Indonesia’s Relationship with the International Olympic Committee, The International Journal of the History of Sport, DOI: 10.1080/09523367.2017.1281801 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2017.1281801 Published online: 22 Feb 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fhsp20 Download by: [93.198.244.140] Date: 22 February 2017, At: 10:11 THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY OF SPORT, 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2017.1281801 The Legacy of the Games of the New Emerging Forces and Indonesia’s Relationship with the International Olympic Committee Friederike Trotier Department of Southeast Asian Studies, Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The Games of the New Emerging Forces (GANEFO) often serve as Indonesia; GANEFO; Asian an example of the entanglement of sport, Cold War politics and the games; Southeast Asian Non-Aligned Movement in the 1960s. Indonesia as the initiator plays games; International a salient role in the research on this challenge for the International Olympic Committee (IOC) Olympic Committee (IOC). The legacy of GANEFO and Indonesia’s further relationship with the IOC, however, has not yet drawn proper academic attention. -

CAPSTONE 20-1 SWA Field Study Trip Book Part II

CAPSTONE 20-1 SWA Field Study Trip Book Part II Subject Page Afghanistan ................................................................ CIA Summary ......................................................... 2 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 3 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 24 Culture Gram .......................................................... 30 Kazakhstan ................................................................ CIA Summary ......................................................... 39 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 40 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 58 Culture Gram .......................................................... 62 Uzbekistan ................................................................. CIA Summary ......................................................... 67 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 68 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 86 Culture Gram .......................................................... 89 Tajikistan .................................................................... CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 99 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 117 Culture Gram .......................................................... 121 AFGHANISTAN GOVERNMENT ECONOMY Chief of State Economic Overview President of the Islamic Republic of recovering -

Code De Conduite Pour Le Water Polo

HistoFINA SWIMMING MEDALLISTS AND STATISTICS AT OLYMPIC GAMES Last updated in November, 2016 (After the Rio 2016 Olympic Games) Fédération Internationale de Natation Ch. De Bellevue 24a/24b – 1005 Lausanne – Switzerland TEL: (41-21) 310 47 10 – FAX: (41-21) 312 66 10 – E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.fina.org Copyright FINA, Lausanne 2013 In memory of Jean-Louis Meuret CONTENTS OLYMPIC GAMES Swimming – 1896-2012 Introduction 3 Olympic Games dates, sites, number of victories by National Federations (NF) and on the podiums 4 1896 – 2016 – From Athens to Rio 6 Olympic Gold Medals & Olympic Champions by Country 21 MEN’S EVENTS – Podiums and statistics 22 WOMEN’S EVENTS – Podiums and statistics 82 FINA Members and Country Codes 136 2 Introduction In the following study you will find the statistics of the swimming events at the Olympic Games held since 1896 (under the umbrella of FINA since 1912) as well as the podiums and number of medals obtained by National Federation. You will also find the standings of the first three places in all events for men and women at the Olympic Games followed by several classifications which are listed either by the number of titles or medals by swimmer or National Federation. It should be noted that these standings only have an historical aim but no sport signification because the comparison between the achievements of swimmers of different generations is always unfair for several reasons: 1. The period of time. The Olympic Games were not organised in 1916, 1940 and 1944 2. The evolution of the programme. -

EL PATO: DE JUEGO SOCIAL a DEPORTE DE ELITE Mer

Recorde: Revista de História do Esporte Artigo volume 1, número 1, junho de 2008 Stela Ferrarese EL PATO: DE JUEGO SOCIAL A DEPORTE DE ELITE Mer. Stela Maris Ferrarese Capettini Universidad Nacional del Comahue Neuquen, Argentina [email protected] Recebido em 28 de janeiro de 2008 Aprovado em 13de março de 2008 Resumen El pato es un juego ancestral argentino practicado con caballos y un pato. El mismo fue incorporado por los gauchos y rechazado por la oligarquía. Actualmente luego de ser convertido en deporte por Rosas, prohibido y recuperado por Perón como deporte nacional esa misma oligarquía se lo apropió y practica como deporte de competición. En otros lugares del país, alejados de la “industria del deporte” se sigue enseñando y practicando entre la “otra parte de la sociedad nacional”. Palabras claves: juego ancestral; deporte; antropologia lúdica. Resumo O pato: de jogo social a um esporte de elite O Pato é um jogo ancestral argentino praticado com cavalos e um pato. O mesmo foi incorporado pelos gaúchos e rejeitado pela oligarquia. Atualmente, após ser convertido em esporte por Rosas, proibido e recuperado por Perón como esporte nacional, essa mesma oligarquia se apropriou dele e o pratica como esporte de competição. Em outros lugares do país, desprovidos da “indústria do esporte”, continua sendo treinado e praticado entre a “outra parte da sociedade nacional”. Palavras-chave: jogo ancestral; esporte; antropologia lúdica. Abstract El pato: from a social game to an elite sport The pato is an ancestral Argentinean game practiced with horses and a duck. The same one which was incorporated by the gauchos and rejected by the oligarchy.