Basic Music Handbook Macworld 2002.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

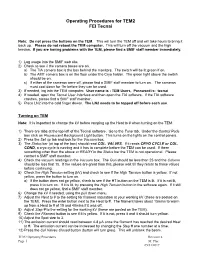

Operating Procedures for TEM2 FEI Tecnai

Operating Procedures for TEM2 FEI Tecnai Note: Do not press the buttons on the TEM. This will turn the TEM off and will take hours to bring it back up. Please do not reboot the TEM computer. This will turn off the vacuum and the high tension. If you are having problems with the TEM, please find a SMIF staff member immediately. 1) Log usage into the SMIF web site. 2) Check to see if the camera boxes are on. a) The TIA camera box is the box behind the monitors. The switch will be lit green if on. b) The AMT camera box is on the floor under the Cryo holder. The green light above the switch should be on. c) If either of the cameras were off, please find a SMIF staff member to turn on. The cameras must cool down for 1hr before they can be used. 3) If needed, log into the TEM computer. User name is : TEM Users, Password is: tecnai 4) If needed, open the Tecnai User Interface and then open the TIA software. If the TIA software crashes, please find a SMIF staff member. 5) Place LN2 into the cold finger dewar. The LN2 needs to be topped off before each use. Turning on TEM Note: It is important to change the kV before ramping up the Heat to # when turning on the TEM. 1) There are tabs at the top left of the Tecnai software. Go to the Tune tab. Under the Control Pads box click on Fluorescent Background Light button. This turns on the lights on the control panels. -

Software User Guide

Cycle Host User's Guide This guide is an evolving document. If you find sections that are unclear, or missing information, please let us know ([email protected]). Please check our website (www.wetlabs.com) periodically for updates. WET Labs, Inc. PO Box 518 Philomath, OR 97370 541-929-5650 fax: 541-929-5277 www.wetlabs.com 28 January 2010 Cycle Host User's Guide Revision 1.04 1/59 Cycle Host Installation The following sub-sections detail the steps necessary to install and run the Cycle Host program (also referred to as "the host") for the first time on a new computer. System Requirements Below are the recommended minimum requirements for a computer to be used to run the host program. Although Windows is currently the only supported operating system, future releases are planned to support Linux and MAC OS as well. Please let us know of your interest in these platforms via [email protected]. Feature Requirements Operating System Windows XP/Vista/2000/2003 (32 and 64 bit versions) Memory 128 Megabytes Disk Space 125 Megabytes (excludes data file storage) Data Port Serial port or USB to Serial adapter supporting 19200 baud Input Devices Keyboard (minimum) Mouse or other pointing device (recommended) Monitor Color, 1024 x 768 (minimum recommended) Table 1: Host Computer System Requirements The Java Runtime Environment The Cycle Host program is written in the JavaTM language developed by Sun Microsystems Inc. For this reason, execution of the host requires the installation of the Java Runtime Environment, or JRE. At the time of this release the current JRE is Version 6 Update 16. -

User Guide 8.2.4

User Guide 8.2.4 Copyright Manual Copyright © 2000-2017 AB Software Consulting Ltd. All rights reserved. AB Software Consulting Ltd. reserves the right to revise this document and to make changes from time to time in the content hereof without obligation to notify any person or persons of such revisions or changes. The software described in this document is supplied under a licence agreement and is protected by UK and international copyright laws. Any implied warranties including any warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose are limited to the terms of the express warranties set out in the licence agreement. Software Copyright © 2000-2017 AB Software Consulting Ltd. All rights reserved. Trademarks AB Tutor is the registered trademark of AB Software Consulting Ltd. Windows, Windows 7/8/10/2003/2008/2012 are trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. Other products, trademarks or registered trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Contents Using AB Tutor Introduction The AB Tutor interface What is AB Tutor? The list view Basic ABT setup The thumbnail view Advanced setup options Commands Introduction to passwords Power commands Startup passwords Connecting to clients Connection password Screen sharing Startup switches Chat (text and audio) Installation Screen Capture Installation on Windows File transfers Installation on Mac OS Key Sequences Installation on iPad Admin commands Activating AB Tutor Launch Push out updates Policies Uninstallation Block printer Remote Deployment Utility Block external drive Site -

Angel® Concentrated Platelet Rich Plasma (Cprp) System - Operator’S Manual

Angel® Concentrated Platelet Rich Plasma (cPRP) System - Operator’s Manual Software Version 1.20 DFU-0263-5 Revision 0 05/2020 This page intentionally left blank Table of Contents Before You Get Started Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. vii Indications for Use ................................................................................................................................... vii Contraindications for Use ......................................................................................................................... vii Warnings .................................................................................................................................................. vii Precautions ............................................................................................................................................... x Additional Information .............................................................................................................................. xii Symbols .................................................................................................................................................. xiii Requirements for the disposal of waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) ........................... xiv Service Information ................................................................................................................................ -

User Manual ( Wins Version 5.26.99 )

Wins Scoring System User Manual ( Wins version 5.26.99 ) Srl STELTRONIC via Artigianale 34 • 25082 Botticino Sera (BS) – ITALY Tel. +39 030 2190811 • Fax + 39 030 2190798 http://www.steltronic.com STELTRONIC S.r.l. via Artigianale Botticino Sera (BS) ITALY - User manual [Wins ver 5.26] 2 Tel. +39 030 2190811 Fax +39 030 2190798 http://www.steltronic.com Thank you for choosing Steltronic. This user manual has been written for Wins version 5.26.99, it is also available in pdf format so that it can installed onto a computer. In order to make it easy to consult, the manual has been divided into chapters each covering different subjects: GENERAL Brief Hardware and Scoring System Architecture description. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ INITIAL USE OF WINDOWS, TURNING THE SYSTEM ON AND OFF Fast guide for ‘first time users’ of the PC and computer system. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ SETUP OF THE WINS PROGRAM Contains all the information relative to the program settings from selecting time zones to changing animations. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ USING THE SYSTEMS FUCTIONS Description of how to use the lane rental, time game, bar and other programs. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ -

Visual Language Features Supporting Human-Human and Human-Computer Communication

Visual Language Features Supporting Human-Human and Human-Computer Communication Jason E. Robbins1, David J. Morley2, David F. Redmiles1, Vadim Filatov3, Dima Kononov3 1 University of California, Irvine 2 Rockwell International 3RR-Gateway, AO Abstract relationships and then try to model them as closely as pos- sible while abstracting details that distract attention from Fundamental to the design of visual languages are the our main concerns. goals of facilitating communication between people and Currently, OBPE exists as a research prototype serving computers, and between people and other people. The to explore the concepts and features that are needed to Object Block Programming Environment (OBPE) is a visual design, programming, and simulation tool which allow effective visual programming in our domain. OBPE emphasizes support for both human-human and human- programs are composed of object blocks, ports, and arcs. computer communication. OBPE provides several features Object blocks use ports as their interface points to the rest to support effective communication: (1) multiple, of the system. Arcs are message passageways between coordinated views and aspects, (2) customizable graphics, ports. Object blocks (or simply, blocks) are visual abstract (3) the “machines with push-buttons” metaphor, and (4) data types [1] which encapsulate state, behavior, visualiza- the host/transient pattern. OBPE uses a diagram-based, tion of state and behavior, and user interface event process- visual object-oriented language that is intended for quickly ing. Furthermore, blocks are first class objects because they designing and programming visual simulations of are instances of normal Smalltalk classes.1 factories. Users interact with OBPE through browsers that allow direct manipulation of blocks and visualization of their 1. -

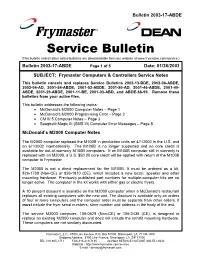

Service Bulletin (This Bulletin and All Other Active Bulletins Are Downloadable from Our Website At

Bulletin 2003-17-ABDE Service Bulletin (This bulletin and all other active bulletins are downloadable from our website at www.frymaster.com/service.) Bulletin 2003-17-ABDE Page 1 of 5 Date: 01/30/2003 SUBJECT: Frymaster Computers & Controllers Service Notes This bulletin cancels and replaces Service Bulletins 2002-13-BDE, 2002-06-ABDE, 2002-04-AD, 2001-54-ABDE, 2001-52-ABDE, 2001-50-AD, 2001-46-ABDE, 2001-40- ABDE, 2001-29-ABDE, 2001-11-BE, 2001-03-ABD, and ABDE-66-99. Remove these bulletins from your active files. This bulletin addresses the following topics: • McDonald’s M2000 Computer Notes – Page 1 • McDonald’s M2000 Programming Error – Page 2 • CM III.5 Computer Notes – Page 3 • Spaghetti Magic III (SMS III) Computer Error Messages – Page 5 McDonald’s M2000 Computer Notes The M2000 computer replaced the M100B in production units on 4/1/2002 in the U.S. and on 6/1/2002 internationally. The M100B is no longer supported and no core credit is available for out-of-warranty M100B computers. If an M100B computer still in warranty is replaced with an M2000, a U.S. $50.00 core credit will be applied with return of the M100B computer to Frymaster. The M2000 is not a direct replacement for the M100B. It must be ordered as a kit, 826-1739 (Non-CE) or 826-1810 (CE), which includes a new bezel, speaker and other mounting hardware. Previously published part numbers for multiple-computer kits are no longer active. The computer in the kit works with either gas or electric fryers. -

V9 User Manual (PDF)

This section of the manual gives a basic introduction to AB Tutor, and describes some of the concepts, such as network layout and passwords. AB Tutor manual Introduction What is AB Tutor? Basic ABT setup Advanced setup options Introduction to passwords Startup passwords Connection password Startup switches Introduction What is AB Tutor? AB Tutor is a networked classroom, instruction, monitoring and teaching tool that lets you train students in a networked classroom or lab, simply, effectively, at a very affordable price. Teachers, trainers and administrators can use the software to easily control, manage, monitor and support their students. This is a list of the key features of AB Tutor Cross platform Windows central server Windows and Mac tutor applications Windows and Mac client applications Computer Monitoring Real-time remote screen watch Simultaneous watch by multiple tutors Network efficient sizeable thumbnail views, with changeable refresh times Create different thumbnail arrangements for each group Monitor running applications and files Identify what site/file the student is working on Monitor and log student activity (applications, printing, websites and keystrokes) Take time and name-stamped snapshots of student activity Record and play back student screen activity Live search for users/computers Monitor multiple class groups simultaneously Keyword Notification Inform tutor when specific keywords are typed Automatically take snapshots of violations Trigger remote screen recording upon violation View and export all violations -

Tutorial Iii: One-Parameter Bifurcation Analysis of Limit Cycles with Matcont Yu.A

tutorial iii: One-parameter bifurcation analysis of limit cycles with matcont Yu.A. Kuznetsov Department of Mathematics Utrecht University Budapestlaan 6 3508 TA, Utrecht N. Neirynck Department of Applied Mathematics, Computer Science and Statistics Ghent University Krijgslaan 281, S9 B-9000, Ghent October 26, 2020 1 This session was tested on MatCont7.0 with MATLAB2018b. It is devoted to the numerical initialization and continuation of limit cycles in systems of autonomous ODEs depending on one parameter n x_ = f(x; α); x 2 R ; α 2 R; and detection of their bifurcations. We will also show how to start the continuation of a limit cycle from the Hopf bifurcation and a doubled cycle from the period-doubling bifurcation. 1 Cycle initialization from a converging orbit We consider again the R¨osslersystem that was introduced in TUTORIAL I: 8 < x_ = −y − z y_ = x + Ay (1) : z_ = Bx − Cz + xz; where (x; y; z) are the phase variables, and (A; B; C) are the parameters. Input system (1) in MatCont, generating the derivatives of order 1, 2 and 3 symbolically. We start with computing by time integration an orbit, using the Starter and Integrator windows presented in Figure 1. Figure 1: The Starter and Integrator windows for the initial time integration. The computed orbit is presented in the 3D-plot in Figure 2 in (x; y; z) - space within the region −9 ≤ x ≤ 9; −9 ≤ y ≤ 9; −2 ≤ z ≤ 11: It is visually clear that the orbit has converged to a (presumably stable) limit cycle. We select the last point of the orbit using SelectjInitial PointjLast PointjSelect Point and clear the Plot3D window. -

User Guide Controls

USER GUIDE CONTROLS DOT MDA 125 UR 5002 Z2 BAINULTRA 956, chemin Olivier, Saint.Nicolas (Quebec) G7A 2N1 Canada Tel.: (418) 831-7701 1 800 463-2187 Fax: (418) 831-6623 1 800 382-8587 [email protected] • www.bainultra.com Printed in Canada. Copyright © May 2005 BainUltra Inc. All rights reserved. 45220000. Some products, specifications, and services in this manual are described in pending patent applications or are protected by patents. USER GUIDE - CONTROLS INDEX I N THIS M ANUAL DOT . .page 5 MDA 125 . .page 7 UR 5002 GENERAL OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS . .page 9 DETAILED INSTRUCTIONS MAIN FUNCTIONS . .pages 10-12 ADVANCED FUNCTIONS . .pages 13-14 Z2 GENERAL OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS . .pages 15-16 MAIN FUNCTIONS LANGUAGE . .page 17 START/ STOP . .page 18 TIME . .page 19 INTENSITY . .page 20 HEAT . .page 21-22 AIR FLOW . .page 23 CHROMATHERAPY . .page 24 CONTACT US . .page 25 ADVANCED FUNCTIONS INVERTING THE SCREEN . .page 26 CONTRAST OF SCREEN . .page 27 DRYING CYCLE ( AUTOMATIC) . .page 28 DRYING CYCLE ( PROGRAMMABLE) . .page 29 Printed in Canada. Copyright © May 2005 BainUltra Inc. All rights reserved. 45220000. www.bainultra.com 3 USER GUIDE - CONTROLS DOT - GENERAL OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS DOT This basic one-touch control lets you adjust massage intensity and activates the automatic drying cycle. START / STOP • Press on the center of the control to start the system. • The system will start at its maximum power and the timer will begin automatically at 20 minutes. • Press once again on the center of the control to stop the system. INTENSITY • Press down on the center of the control and maintain a constant pressure to adjust the intensity of the massage.The power of the air jets will slowly decrease to its lowest speed and if you maintain pressure on the control, it will slowly increase to its highest speed. -

New POWER User Manual

2019 New POWER User Manual v2.1 New POWER User Manual Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 About the project ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Software dependencies .............................................................................................................................. 4 Names and Definitions ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Cycle ................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Limits ............................................................................................................................................................... 6 Configuration Files............................................................................................................................................ 7 Configuration file types ............................................................................................................................... 7 Default configuration path .......................................................................................................................... 7 Basic Configuration ......................................................................................................................................... -

Database of Visual and Source Code Components

Conclusion Initially, taking into consideration available resources, we attempt to build a polarity lexicon for Ukrainian language. In this paper we tried to tackle this problem employing graph polarity propagation algorithm. Since this pilot experiment was encouraging, this allows us in future work to generate the lexicon for Ukrainian language. It should be stressed that the present research is aimed at laying a foundation for further researches in the field of sentiment analysis in Ukraine. 1. Agerri, R. Q-WordNet: Extracting polarity from WordNet senses / R. Agerri, A. Garcia-Serrano // Seventh Conference on International Language Resources and Evaluation, Malta, 2010. 2. Baccianella S. SentiWordNet 3.0: An enhanced lexical resource for sentiment analysis and opinion mining / S. Baccianella et al.// Proceedings of the 7th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC'10). Valletta, 2010. Р. 2200–2204, 3. Esuli A. SentiWordNet: A publicly available lexical resource for opinion. – mining/ A. Esuli, F. Sebastiani // In Proceedings of the 5th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC'06). Citeseer, Genova, 2006. – Р. 417. 4. Hatzivassiloglou V. Predicting the semantic orientation of adjectives / Vasileios Hatzivassiloglou and Kathleen McKeown // In Proc. of the 35th ACL/8th EACL. – Р. 174–181, 1997. 5. Hu M. Mining and Summarizing Customer Reviews / M. Hu, and B. Liu // In KDD, 2004. 6. Liu B. Sentiment Analysis and Subjectivity / B. Liu // Handbook of Natural Language Processing, Second Edition, 2010. 7. Miller, G. WordNet: A lexical database for English /G. Miller // Communications of the ACM. – 1995. 11. – Р. 38. 8. Santos A. P. Determining the Polarity of Words through a Common Online Dictionary / A.