Object Model of Relationships Between Children and Adults

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mr. Ms. First Name FAMILY NAME Section Or Unit/Title/Position/Rank

Mr. First Name FAMILY NAME Section or Unit/Title/Position/Rank Ms. DELEGATIONS ALBANIA Albania Mr. Alqiviadhi PULI Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Albania Mr. Spiro KOÇI Ambassador, Permanent Representative Albania Ms. Ravesa LLESHI Advisor Albania Mr. Glevin DERVISHI Advisor Albania Mr. Xhodi SAKIQI Counsellor GERMANY Germany Dr. Guido WESTERWELLE Minister Germany Mr. Rüdiger LÜDEKING Ambassador, Head of Permanent Mission to the OSCE Germany Mr. Juergen SCHULZ Deputy Political Director Germany Mr. Thomas OSSOWSKI Deputy Head of Minister’s Office Germany Mr. Martin SCHÄFER Deputy Federale Foreign Office Spokesperson Germany Mr. Thomas Eberhard SCHULTZE Head of OSCE Division Germany Ms. Christine WEIL Deputy Head of Permanent Mission to the OSCE Germany Mr. Hans-Henning PRADEL Senior Military Adviser Germany Mr. Steffen FEIGL Bagage Master Germany Mr. Bernd PFAFFENBACH Military Adviser Germany Ms. Heike JANTSCH Counsellor Germany Mr. Detlef HEMPEL Military Adviser Germany Mr. Holger LEUKERT Desk Officer Ministry of Defence Germany Ms. Anne DR. WAGNER-MITCHELL Counsellor Germany Mr. Jean P. FROEHLY Counsellor Germany Mr. Julian LÜBBERT First Secretary Germany Ms. Annette PÖLKING First Secretary Germany Mr. Anna SCHRÖDER First Secretary Germany Mr. Stephan FAGO Second Secretary Germany Ms. Anna-Elisabeth VOLLERT Assistant Attacheé Germany Mr. Sören HEINE Assistent Senior Military Adviser Germany Mr. Joerg Emil GAUDIAN Protocol desk officer Germany Mr. Bruno WOBBE Communication Germany Mr. Thomas KÖHLER Official Fotograph Germany Mr. Christof WEIL Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Germany Ms. Anka FELDHUSEN Minister Counsellor and Deputy Head of Mission Germany Ms. Daniela BERGELT First Secretary Germany Mr. Christopher FUCHS First Secretary Germany Ms. Tanja BEYER First Secretary Germany Mr. -

Religious Studies 1.800.405.1619/Yalebooks.Com

2019 RELIGIOUS STUDIES 1.800.405.1619/yalebooks.com Radical Sacrifice Restless Secularism TERRY EAGLETON Modernism and the Religious Inheritance Terry Eagleton pursues the concept of MATTHEW MUTTER sacrifice through the history of human Through a study of Wallace Stevens, thought, from antiquity to modernity, in Virginia Woolf, and other major writers, religion, politics, and literature. He sheds this thoughtful and provocative survey skewed perceptions of the idea, honing in of modernist literature explores how on a radical structural reconception that modernism understood the far-reaching relates the ancient world to our own in consequences of secularism for key fields terms of civilization and violence. of experience: language, aesthetics, Hardcover 2018 216 pp. emotion, and material life. 978-0-300-23335-3 $25.00 HC - Paper over Board 2017 336 pp. 978-0-300-22173-2 $85.00 & The New Cosmic Story Inside Our Awakening Universe & Before Religion JOHN F. HAUGHT A History of a Modern Concept In this inviting and thought-provoking BRENT NONGBRI book a foremost thinker on the intersec- Examining a wide array of ancient tion of science and religion argues that writings, Nongbri demonstrates that in an adequate understanding of cosmic antiquity, there was no conceptual arena history cannot be based on science that could be designated as “religious” alone. It must also take into account as opposed to “secular.” Surveying the implications of the awakening of representative episodes from a two- interiority and religious awareness. thousand-year period, Nongbri offers Hardcover 2017 240 pp. a concise and readable account of the 978-0-300-21703-2 $25.00 emergence of the concept of religion. -

Nation Making in Russia's Jewish Autonomous Oblast: Initial Goals

Nation Making in Russia’s Jewish Autonomous Oblast: Initial Goals and Surprising Results WILLIAM R. SIEGEL oday in Russia’s Jewish Autonomous Oblast (Yevreiskaya Avtonomnaya TOblast, or EAO), the nontitular, predominately Russian political leadership has embraced the specifically national aspects of their oblast’s history. In fact, the EAO is undergoing a rebirth of national consciousness and culture in the name of a titular group that has mostly disappeared. According to the 1989 Soviet cen- sus, Jews compose only 4 percent (8,887/214,085) of the EAO’s population; a figure that is decreasing as emigration continues.1 In seeking to uncover the reasons for this phenomenon, I argue that the pres- ence of economic and political incentives has motivated the political leadership of the EAO to employ cultural symbols and to construct a history in its effort to legitimize and thus preserve its designation as an autonomous subject of the Rus- sian Federation. As long as the EAO maintains its status as one of eighty-nine federation subjects, the political power of the current elites will be maintained and the region will be in a more beneficial position from which to achieve eco- nomic recovery. The founding in 1928 of the Birobidzhan Jewish National Raion (as the terri- tory was called until the creation of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast in 1934) was an outgrowth of Lenin’s general policy toward the non-Russian nationalities. In the aftermath of the October Revolution, the Bolsheviks faced the difficult task of consolidating their power in the midst of civil war. In order to attract the support of non-Russians, Lenin oversaw the construction of a federal system designed to ease the fears of—and thus appease—non-Russians and to serve as an example of Soviet tolerance toward colonized peoples throughout the world. -

PRISM Vol. 2 No 4

PRISM❖ Vol. 2, no. 4 09/2011 PRISM Vol. 2, no. 4 2, no. Vol. ❖ 09/2011 www.ndu.edu A JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR COMPLEX OPERATIONS TITLE FEATURES 3 Transforming the Conflict in Afghanistan by Joseph A. L’Etoile 17 State-building: Job Creation, Investment Promotion, and the Provision of Basic Services by Paul Collier 31 Operationalizing Anticipatory Governance ndupress.ndu.edu by Leon Fuerth www.ndu.edu/press 47 Colombia: Updating the Mission? by Carlos Alberto Ospina Ovalle 63 Reflections on the Human Terrain System During the First 4 Years by Montgomery McFate and Steve Fondacaro 83 Patronage versus Professionalism in New Security Institutions by Kimberly Marten 99 Regional Engagement in Africa: Closing the Gap Between Strategic Ends and Ways by Laura R. Varhola and Christopher H. Varhola 111 NATO Countering the Hybrid Threat by Michael Aaronson, Sverre Diessen, Yves de Kermabon, Mary Beth Long, and Michael Miklaucic FROM THE FIELD 125 COIN in Peace-building: Case Study of the 2009 Malakand Operation by Nadeem Ahmed LESSONS LEARNED 139 The Premature Debate on CERP Effectiveness by Michael Fischerkeller INTERVIEW 151 An Interview with Richard B. Myers BOOK REVIEW 160 The Future of Power Reviewed by John W. Coffey PRISM wants your feedback. Take a short survey online at: www.ccoportal.org/prism-feedback-survey PRISMPRISM 2, no. 4 FEATURES | 1 AUTHOR Afghan and U.S. commandos reinforce Afghan government presence in remote villages along Afghanistan-Pakistan border U.S. Army (Justin P. Morelli) U.S. Army (Justin P. Transforming the Conflict in Afghanistan BY JOSEPH A. L’ETOILE any have characterized the war in Afghanistan as a violent political argument between the government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (with its coalition partners) and Mthe Taliban, with the population watching and waiting to decide whom to join, and when. -

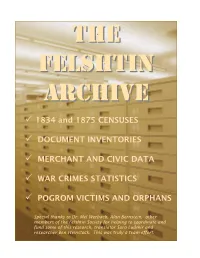

1834 and 1875 CENSUSES DOCUMENT INVENTORIES

THETHE FELSHTINFELSHTIN ARCHIVEARCHIVE 3 1834 and 1875 CENSUSES 3 DOCUMENT INVENTORIES 3 MERCHANT AND CIVIC DATA 3 WAR CRIMES STATISTICS 3 POGROM VICTIMS AND ORPHANS Special thanks to Dr. Mel Werbach, Alan Bernstein, other members of the Felshtin Society for helping to coordinate and fund some of this research, translator1 Sora Ludmir and researcher Ben Weinstock. This was truly a team effort. Chronological List of Archival Documents That Include Information About Felshtin 1765-1914 Last Updated 6/08 Note: data from some of the following documents and from the Felshtin yizkor book were compiled in the Felshtin Who’s Who that appears in www.felshtin.org. Note that the Kamenets-Podolsk Archive was closed after the fire in April 2003 and merged with the Archival department of municipal authority. All fonds were transferred to the State Archives of Khmelnytskyi Oblast. 1765, 1775, Arkhiv Jugo-Zapadnoj Rossii, part 1840, List of Recruits, Jews of Podolskiy V, Vol. 2. Researched by Adam Kazmierczyk, Gubernia, Fond 226, inventory 79, file 4863, Warsaw Poland. Lists a few notable Felshtin Jews Kamenets-Podolsk Archive. in 1765 and 1775. 1841, Lists of bourgeoise of all Uezds of 1796-1867, Army records, Fond 29, inventory Podolskiy Gubernia, Fond 226, inventory 79, file 1, Kamenets-Podolsk Archive 4885, Kamenets-Podolsk Archive. 1796-1867, census, Fond 29, inventory 1 1841, Reviskie Skazky of all Uezds of Podolskiy 1796-1867, Kahal/Jewish community, Fiond 29, Gubernia, Fond 226, inventory 79, files 4889 and inventory 1, Kamenets-Podolsk Archive. 4990, Kamenets-Podolsk Archive. 1816, Revision Registers of Proskurov District, 1844, Additional Reviskie Skazky of Jews of Kamenets-Podolsk Archive, Borough of Felshtin, Podolskiy Gubernia, Fond 226, inventory 80, file Fond 226, Podolia State Treasury. -

Annual Review 2014–2015 PB | 01 Contents

Annual Review 2014– 2015 DR PATRICK PRENDERGAST PROVOST & PRESIDENT Annual Review 2014–2015 PB | 01 Contents 01 01.0 Provost’s Introduction 02 02 02.0 Trinity at a Glance 06 03 03.0 Research Case Studies 14 03.1 Yuri Volkov 16 03.2 Poul Holm 18 03.3 Roja Fazaeli 20 03.4 Anne-Marie Healy 22 03.5 Darryl Jones 24 03.6 Samson Shatashvili 26 03.7 Luke O’Neill 28 03.8 Linda Hogan 30 03.9 Brian O’Connell 32 03.10 Paul Delaney 34 03.11 Valeria Nicolosi 36 03.12 Linda Doyle 38 04 04.0 Innovation 40 05 05.0 Public Engagement 44 06 06.0 The Student Experience 48 07 0 7. 0 Trinity’s Online Education 52 08 08.0 New Professor Interviews 56 08.1 Jane Alden 58 08.2 Mark Bell 61 08.3 Orla Hardiman 64 08.4 Douglas Leith 67 08.5 Richard Layte 69 08.6 Andrew Burke 72 08.7 Seamas Donnelly 75 08.8 Eleanor Molloy 78 08.9 Cathal Moran 81 09 09.0 Trinity Growing Globally 84 10 10.0 Philanthropy and Alumni Engagement 88 11 11.0 Trinity’s Visitors 92 12 12.0 A Sporting Year to Remember 96 13 13.0 Financial Elements 100 Trinity College Dublin — The University of Dublin Annual Review 2014–2015 02 | 01 01 Introduction from the Provost The academic year began with the launch of our Neurology and Orthopaedics & Sports Medicine — are newly new Strategic Plan in October 2014, laying out our priorities created full-time professorships, firsts for Trinity and for Ireland. -

Southeastern Regional Taxonomic Center South Carolina Department of Natural Resources

Southeastern Regional Taxonomic Center South Carolina Department of Natural Resources http://www.dnr.sc.gov/marine/sertc/ Southeastern Regional Taxonomic Center Invertebrate Literature Library (updated 9 May 2012, 4056 entries) (1958-1959). Proceedings of the salt marsh conference held at the Marine Institute of the University of Georgia, Apollo Island, Georgia March 25-28, 1958. Salt Marsh Conference, The Marine Institute, University of Georgia, Sapelo Island, Georgia, Marine Institute of the University of Georgia. (1975). Phylum Arthropoda: Crustacea, Amphipoda: Caprellidea. Light's Manual: Intertidal Invertebrates of the Central California Coast. R. I. Smith and J. T. Carlton, University of California Press. (1975). Phylum Arthropoda: Crustacea, Amphipoda: Gammaridea. Light's Manual: Intertidal Invertebrates of the Central California Coast. R. I. Smith and J. T. Carlton, University of California Press. (1981). Stomatopods. FAO species identification sheets for fishery purposes. Eastern Central Atlantic; fishing areas 34,47 (in part).Canada Funds-in Trust. Ottawa, Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, by arrangement with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, vols. 1-7. W. Fischer, G. Bianchi and W. B. Scott. (1984). Taxonomic guide to the polychaetes of the northern Gulf of Mexico. Volume II. Final report to the Minerals Management Service. J. M. Uebelacker and P. G. Johnson. Mobile, AL, Barry A. Vittor & Associates, Inc. (1984). Taxonomic guide to the polychaetes of the northern Gulf of Mexico. Volume III. Final report to the Minerals Management Service. J. M. Uebelacker and P. G. Johnson. Mobile, AL, Barry A. Vittor & Associates, Inc. (1984). Taxonomic guide to the polychaetes of the northern Gulf of Mexico. -

Minutes General Assembly, 10Th October 2009, Continued

INTERNATIONAL MOUNTAINEERING AND CLIMBING FEDERATION UNION INTERNATIONALE DES ASSOCIATIONS D’ALPINISME M I N U T E S UIAA GENERAL ASSEMBLY Porto, Portugal 10th October 2009, 08:30 – 18:00 Members present or represented by proxy (Bold = full voting rights) Belgium CMBEL Climbing & Mountaineering Belgium Paul Verzele Canada ACC Alpine Club of Canada Cameron Roe China CMA Chinese Mountaineering Association Yongfeng Wang Chinese Taipei CTAA Chinese Taipei Alpine Association Chang-Hsien Hsieh Chinese Taipei CTMA Chinese Taipei Mountaineering Association Hank Hwang Denmark DB Dansk Bjergklub / Danish Mountain Club Jan Elleby Denmark DCF Danish Climbing Federation Jan Elleby Fédération Française des Clubs Alpins et de France FFCAM Georges Elziere Montagne Great Britain TAC The Alpine Club Martin Scott Great Britain BMC British Mountaineering Council Doug Scott Greece EOOA Hellenic Federation of Mountaineering and Climbing Dimitris Georgoulis Hong Kong, China HKMU Hong Kong Mountaineering Union Frederick Yu I.R. Iran Mountaineering and Sport Climbing Iran IRIMSCF Mahmoud Shoaei Federation Italy CAI Club Alpino Italiano Stefano Tirinzoni Japan JMA Japan Mountaineering Association Fumio Tanaka Korea KAF Korean Alpine Federation Christine Pae Nepal NMA Nepal Mountaineering Association Zimba Zangbu Sherpa Netherlands NKBV Royal Dutch Mountaineering and Climbing Club Frits Vrijlandt New Zealand NZAC New Zealand Alpine Club John Nankervis Norway NTK Norsk Tindeklub / Norwegian Alpine Club Ragnhild Amundsen Poland PZA Polish Mountaineering Association -

The Region and the World: the Case of Nizhnii Novgorod

Eidgenössische “Regionalization of Russian Foreign and Security Policy” Technische Hochschule Zürich Project organized by The Russian Study Group at the Center for Security Studies and Conflict Research Andreas Wenger, Jeronim Perovic,´ Andrei Makarychev, Oleg Alexandrov WORKING PAPER NO.6 MAY 2001 The Region and the World: The Case of Nizhnii Novgorod DESIGN : SUSANA PERROTTET RIOS This paper gives a thorough account of the factors that foster or inhibit Nizhnii By Andrei S. Makarychev Novgorod’s efforts to become a player in the national and international arenas. The author of this study sees opportunities and hurdles for the region’s integration into international economic (but also political and social) structures. This process, which started in the early 1990s, was much more lengthy and time consuming than was ini- tially expected. There have been objective reasons for this development (the general crisis of the Russian economy, lack of a globally oriented sector of the regional mar- ket) as well as subjective ones (foreign policy misperceptions of local elites, admin- istrative inertia and lack of well-trained managers). The author argues that the region’s economic and financial projects might in the future realistically be integrated into a wider international geopolitical and geoeconomic framework. Thanks to a rel- atively liberal leadership, experiences in the field of international cooperation and the strong presence of foreign economic actors in the region, business professionals and policy-makers from Nizhnii Novgorod are gradually adapting to the basic norms and rules of the international business and political community and understand the necessity to improve the quality standards of domestic production. -

College of Wooster Miscellaneous Materials: a Finding Tool

College of Wooster Miscellaneous Materials: A Finding Tool Denise Monbarren August 2021 Box 1 #GIVING TUESDAY Correspondence [about] #GIVINGWOODAY X-Refs. Correspondence [about] Flyers, Pamphlets See also Oversized location #J20 Flyers, Pamphlets #METOO X-Refs. #ONEWOO X-Refs #SCHOLARSTRIKE Correspondence [about] #WAYNECOUNTYFAIRFORALL Clippings [about] #WOOGIVING DAY X-Refs. #WOOSTERHOMEFORALL Correspondence [about] #WOOTALKS X-Refs. Flyers, Pamphlets See Oversized location A. H. GOULD COLLECTION OF NAVAJO WEAVINGS X-Refs. A. L. I. C. E. (ALERT LOCKDOWN INFORM COUNTER EVACUATE) X-Refs. Correspondence [about] ABATE, GREG X-Refs. Flyers, Pamphlets See Oversized location ABBEY, PAUL X-Refs. ABDO, JIM X-Refs. ABDUL-JABBAR, KAREEM X-Refs. Clippings [about] Correspondence [about] Flyers, Pamphlets See Oversized location Press Releases ABHIRAMI See KUMAR, DIVYA ABLE/ESOL X-Refs. ABLOVATSKI, ELIZA X-Refs. ABM INDUSTRIES X-Refs. ABOLITIONISTS X-Refs. ABORTION X-Refs. ABRAHAM LINCOLN MEMORIAL SCHOLARSHIP See also: TRUSTEES—Kendall, Paul X-Refs. Photographs (Proof sheets) [of] ABRAHAM, NEAL B. X-Refs. ABRAHAM, SPENCER X-Refs. Clippings [about] Correspondence [about] Flyers, Pamphlets ABRAHAMSON, EDWIN W. X-Refs. ABSMATERIALS X-Refs. Clippings [about] Press Releases Web Pages ABU AWWAD, SHADI X-Refs. Clippings [about] Correspondence [about] ABU-JAMAL, MUMIA X-Refs. Flyers, Pamphlets ABUSROUR, ABDELKATTAH Flyers, Pamphlets ACADEMIC AFFAIRS COMMITTEE X-Refs. ACADEMIC FREEDOM AND TENURE X-Refs. Statements ACADEMIC PROGRAMMING PLANNING COMMITTEE X-Refs. Correspondence [about] ACADEMIC STANDARDS COMMITTEE X-Refs. ACADEMIC STANDING X-Refs. ACADEMY OF AMERICAN POETRY PRIZE X-Refs. ACADEMY SINGERS X-Refs. ACCESS MEMORY Flyers, Pamphlets ACEY, TAALAM X-Refs. Flyers, Pamphlets ACKLEY, MARTY Flyers, Pamphlets ACLU Flyers, Pamphlets Web Pages ACRES, HENRY Clippings [about] ACT NOW TO STOP WAR AND END RACISM X-Refs. -

The Unraveling of Russia's Far Eastern Power by Felix K

The Unraveling of Russia's Far Eastern Power by Felix K. Chang n the early hours of September 1, 1983, a Soviet Su-15 fighter intercepted and shot down a Korean Airlines Boeing 747 after it had flown over the I Kamchatka Peninsula. All 269 passengers and crew perished. While the United Statescondemned the act as evident villainyand the Soviet Union upheld the act as frontier defense, the act itselfunderscored the militarystrength Moscow had assembled in its Far Eastern provinces. Even on the remote fringes of its empire, strong and responsive militaryforces stood ready. As has been the case for much of the twentieth century, East Asia respected the Soviet Union and Russialargely because of their militarymight-with the economics and politics of the Russian Far East (RFE) playing important but secondary roles. Hence, the precipitous decline in Russia's Far Eastern forces during the 1990s dealt a serious blow to the country's power and influence in East Asia. At the same time, the regional economy's abilityto support itsmilitaryinfrastructure dwindled. The strikes, blockades, and general lawlessness that have coursed through the RFE caused its foreign and domestic trade to plummet. Even natural resource extraction, still thought to be the region's potential savior, fell victim to bureaucratic, financial, and political obstacles. Worse still, food, heat, and electricityhave become scarce. In the midst of this economic winter, the soldiers and sailors of Russia's once-formidable Far East contingent now languish in their barracks and ports, members of a frozen force.1 Political Disaggregation Since the fall of the Soviet Union, the RFE's political landscape has been littered with crippling conflicts between the center and the regions, among the 1 For the purposes of this article, the area considered to be the Russian Far East will encompass not only the administrative district traditionally known as the Far East, but also those of Eastern Siberia and Western Siberia. -

American Association of Teachers of Slavic and Fast Orthographic

DOCUKENT RFSUME ED 046 259 FL 001 420 AUTHOR Benson, Morton TITLE 'the stress of Fussian Surnames. TNSTITUTION American Association of Teachers of Slavic and Fast European Languages. PUB DATE 64 NOTE 12n. JOURNAL CIT Slavic and Fast European Journal; vF n1 n42-.? Stir 1064 ?DRS PRICE EDRS Price HC -T3.29 DFSCRIPTORS Applied Linguistics, Corm Classes (Languaces), Intonation, *1,anguage Patterns, *Norinals, Orthographic Symbols, *Phonology, *7ussian, Languages, Spelling, Suprasegmentals ABSTRACT An investigation of Fussian surnames reveals a system in which pronunciation is largtly determined by two sets of factors. The author co:Isiders in detail the relationship between the stress in a surname anl the stress in a word from which the name is derived and also the relationship betAeen the stress in surnames and their "endings" as they are written in traditional orthography. Tt is demonstrated that, while most Russial. surnames are systematically derived, many exceptions and individual pronunciations do exist. (RT) raLebra. r US DEPARTMENT OF HEWN. EDUCATION 0 WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS COPYRIGHTED TOTEM HAS BEEN GRANTED MS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVEDFROMTHE 0_044 PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECISSARLLY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION 10 ERIC AND OR 1111,1110S OPERATING POSITION OR POLICY. UNDER AGREEMENTS WITH THE U.S. OFFICE OF EDUCATION. FURTHER REPRODUCTION OUTSIDE THE ERIC SYSTEM REOUIRES PERMISSION OF THE COPYRIGHT OWNER." The Stress of Rusbian Surnames By Morton Benson CD University of Pennsylvania Ci u-/ To the non-native speaker of Russian, the stress of Russiansur- names often seems hopeler sly complex.' One investigator cites, for example, an unnamed American student of Russian who laments: "If there are threesyllablesin a Soviet surname,my first two choices will be wrong ones.