Fourth Amendment Motion to Suppress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durrenberger V. Texas Department of Criminal Justice

Case 4:09-cv-00786 Document 51 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 1 of 5 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS HOUSTON DIVISION JEREMY JOSEPH DURRENBERGER, § Plaintiff, § § v. § CIVIL ACTION NO. 4:09-CV-00786 § TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF § CRIMINAL JUSTICE, § Defendant. § TDCJ’S MOTION FOR RECONSIDERATION OF THE COURT’S ORDER GRANTING DURRENBERGER’S MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT TO UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE SIM LAKE: Pursuant to Rule 60 of the FEDERAL RULES OF CIVIL PROCEDURE, TDCJ, by counsel, the Texas Attorney General, submits this Motion requesting the Court reconsider Its Order granting Durrenberger’s Motion for Summary Judgment. NATURE AND STAGE OF PROCEEDINGS Durrenberger filed suit claiming disability discrimination under the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Rehabilitation Act. Durrenberger complained his hearing loss prevented him from participation in visitation with an inmate. The Court has determined Durrenberger is hearing impaired and that TDCJ discriminated against Durrenberger by failing to accommodate Durrenberger’s disability with an auxiliary hearing device or an attorney-client booth visit. TDCJ seeks reconsideration of the Court’s ruling because: 1) Durrenberger’s admission that he has not used or carried an auxiliary device set against his claim he is entitled to an auxiliary aid at TDCJ presents a factual issue for the jury as to whether he has a disability and whether TDCJ reasonably accommodated any disability and 2) a factual dispute remains regarding the Rehabilitation Act Case 4:09-cv-00786 Document 51 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 2 of 5 causation factor necessary to a determination of intentional discrimination. -

Editor's Note

Published by the Bolch Judicial Institute at Duke Law. Reprinted with permission. © 2021 Duke University School of Law. All rights reserved. JUDICATURE.DUKE.EDU 2 JUDICATURE VOL. 101 NO. 1 EDITOR IN CHIEF CHIEF JUSTICE JOHN ROBERTS CREATED A STIR IN 2011 FOR SUGGESTING THAT MUCH LEGAL “Pick up a copy of any law review,” ribbed DON WILLETT SCHOLARSHIP OFFERS SCANT PRACTICAL INSIGHT. Justice, Supreme Court of Texas the Chief Justice, “and the first article is likely to be . the influence of Immanuel Kant on evidentiary approaches in 18th Century Bulgaria.” BOARD OF EDITORS The Chief Justice, who frequently cites relevant scholarship, was lightheartedly noting DINAH ARCHAMBEAULT what others have long lamented: the disjunction between legal academia and the bread-and- Judge, Twelfth Judicial Circuit Court, Illinois butter work of lawyers and judges. FREDERIC BLOCKX Judicature, for its part, need never fret over its usefulness. Our BRIEFS Judge, Commerical Court, Belgium unfussy aim — to be relentlessly relevant — rarely misses the bull’s-eye. MARK DAVIS This edition’s “cover story” showcases a hot-off-the-press report from Judge, North Carolina Court of Appeals the Conference of Chief Justices, an urgent call for civil justice improve- ments to ensure that state courts remain “affordable for all, efficient MEMBERS OF THE BOARD for all, and fair for all.” The article, co-authored by Oregon Chief JENNIFER BAILEY Justice Thomas Balmer and Judge Gregory Mize, discusses the CCJ’s Judge, 11th Judicial Circuit Court, Florida far-reaching reform proposals to meet 21st-century needs. These are CHERI BEASLEY concrete reforms, not rhetorical meringue, and rooted in a simple, yet Justice, Supreme Court often overlooked, truth: Courts exist to serve real people facing real of North Carolina challenges in the real world. -

View Procedures

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS HOUSTON DIVISION JUDGE KENNETH M. HOYT THE ATTACHED COVER PAGE MUST BE SERVED WITH THE SUMMONS AND COMPLAINT OR NOTICE OF REMOVAL Presented are Court Procedures and attachments that are applicable to cases assigned to Judge Kenneth M. Hoyt. The plaintiff must serve this cover page and the Order for Conference along with the summons and complaint on all defendants. A party removing a case to this Court has the same obligation as a plaintiff filing an Original Complaint. Proof of service of these materials must be filed with the Clerk. A form certificate for use in removed cases is attached to these materials. Additionally, the parties may, at their election, proceed with their case before a U.S. Magistrate Judge. A consent form and related instructions may be obtained on the District Court’s website at www.txs.uscourts.gov. The accompanying procedures are to be used in conjunction with the Local Rules for the Southern District of Texas and not as a substitute for them. The Local Rules as well as this Court’s procedures may also be obtained at www.txs.uscourts.gov. The Court requires strict compliance with the Local Rules and its procedures. Revised: March 2013 THE HONORABLE KENNETH M. HOYT UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE United States Courthouse Courtroom No. 11A 515 Rusk, 11th Floor, Room 11-144 Telephone: (713) 250 - 5613 Facsimile: (713) 250 - 5368 CYNTHIA HORACE Case Manager for Judge Kenneth M. Hoyt P. O. Box 61010 Houston, Texas 77208 Telephone: (713) 250 - 5515 Email: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Contact with Court Personnel. -

Texas Law Judicial Clerks List

Texas Law Judicial Clerks List This list includes Texas Law alumni who reported their clerkships to the Judicial Clerkship Program – or whose names were published in the Judicial Yellow Book or Martindale Hubbell – and includes those who clerked during the recent past for judges who are currently active. There are some judges and courts for which few Texas Law alumni have clerked – in these cases we have listed alumni who clerked further back or who clerked for judges who are no longer active. Dates following a law clerk or judge’s name indicate year of graduation from the University of Texas School of Law. Retired or deceased judges, or those who has been appointed to another court, are listed at the end of each court section and denoted (*). Those who wish to use the information on this list will need to independently verify the information being used. Federal Courts U.S. Supreme Court ............................................................................................................. 2 U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeals ............................................................................................. 3 First Circuit Second Circuit Third Circuit Fourth Circuit Fifth Circuit Sixth Circuit Seventh Circuit Eighth Circuit Ninth Circuit Tenth Circuit Eleventh Circuit Federal Circuit District of Columbia Circuit U.S. Courts of Limited Jurisdiction ...................................................................................... 9 Executive Office for Immigration Review U.S. Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces U.S. Court of Appeals for Veteran Claims U.S. Court of Federal Claims U.S. Court of International Trade U.S. Tax Court U.S. District Courts (listed alphabetically by state) ............................................................ 10 State Courts State Appellate Courts (listed alphabetically by state) ........................................................ 25 State District & County Courts (listed alphabetically by state) .......................................... -

Legal Powerhouse

BRIEFCASE SIX ALUMNI REACH GREAT HEIGHTS LEGAL POWERHOUSE 2016 BRIEFCASE Volume 34 SIX ALUMNI REACH GREAT HEIGHTS Number 1 Cover design: Elena Hawthorne BRIEFCASE LEGAL POWERHOUSE University of Houston Law Center - Please direct correspondence to: Carrie Anna Criado Institutes, Centers, and Select Programs Briefcase Editor University of Houston A.A. White Dispute Resolution Institute Law Center Director, Ben Sheppard 4604 Calhoun Road Houston, TX 77204-6060 Blakely Advocacy Institute [email protected] Director, Jim Lawrence ’07 713.743.2184 Center for Biotechnology & Law 713.743.2122 (fax) Director, Barbara J. Evans, George Butler Research Professor of Law Writers John T. Brannen, Carrie Anna Criado, Kenneth M. Fountain, John T. Kling, Center for Children, Law & Policy Glenda Reyes, Laura Tolley Director, Ellen Marrus, George Butler Research Professor of Law Photographer Elena Hawthorne, Stephen B. Jablonski Design Seleste Bautista, Eric Dowding, Center for Consumer Law Elena Hawthorne Director, Richard M. Alderman, Professor Emeritus Printing UH Printing Services Center for U.S. and Mexican Law UH Law Center Administration Director, Stephen Zamora, Professor Emeritus Dean and Professor of Law Criminal Justice Institute Leonard M. Baynes Director, Sandra Guerra Thompson, Alumnae College Professor of Law Associate Dean and Associate Professor of Law Marcilynn A. Burke Environment, Energy & Natural Resources Center Director, O’Quinn Law Library and Associate Professor of Law Director, Bret Wells, Associate Professor of Law Spencer L. Simons Health Law & Policy Institute Associate Dean for Student Affairs Director, Jessica L. Roberts, Associate Professor of Law Sondra Tennessee Co-director, Jessica L. Mantel, Assistant Professor of Law Associate Dean of External Affairs Russ Gibbs Institute for Higher Education Law and Governance Assistant Dean for Information Technology Director, Michael A. -

United States District Court Southern District of Texas

Case 4:12-cv-01833 Document 16 Filed in TXSD on 11/15/12 Page 1 of 3 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS TEXAS AGGIE CONSERVATIVES, a recognized student organization at Texas A&M University, Plaintiff, v. R. BOWEN LOFTIN, individually and in his official capacity as President of Texas A&M University; Lt. Gen. JOSEPH WEBER, individually and in his official capacity as Vice President of Student Affairs at Texas A&M University; WILLIAM B. STACKMAN, individually and in his official capacity as Case No. 4:12-cv-1833 Director of Student Activities at Texas A&M University; ROSEMARY SCHOENFELD, Hon. Sim Lake JOHN T. SWEENEY, CYNTHIA A. OLVERA, LAURA A. SIGLE, SOMBRA NOTICE OF SETTLEMENT AND DAVIS, KATHRYN G. KING, TONYA VOLUNTARY DISMISSAL DRIVER, MELISSA R. SHEHANE, LINDA D. LEWIS, and TRACIE A. LOWE, all individually and in their official capacities as Texas A&M University employee members of the Student Organization Advisory Board; SAMANTHA L. ALVIS, CHAO HUANG, ROBERT C. SCOGGINS, STEPHEN N. BARNES, HOA T. NGUYEN, KELSEY HANES, and EMILY E. SCHARNBERG, all in their official capacities as Texas A&M University student members of the Student Organization Advisory Board, Defendants. Plaintiff Texas Aggie Conservatives, by and through counsel, and pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 41(a)(1)(A)(i), hereby states as follows: Plaintiff filed a verified complaint on June 19, 2012. On October 9, 2012, the Court extended the deadline for service to December 17, 2012. Case 4:12-cv-01833 Document 16 Filed in TXSD on 11/15/12 Page 2 of 3 Pursuant to Fed. -

List of Contact Information About the Members of the Judicial Conference of the United States (The Highest Policy-Making Body of the Federal Judiciary, 28 U.S.C

List of Contact Information About the Members of the Judicial Conference of the United States (the highest policy-making body of the Federal Judiciary, 28 U.S.C. §331) For the list of members as of the last January 2008, go to http://www.uscourts.gov/judconf/members/2008.html For further information about any member, find the respective court through http://www.uscourts.gov/courtlinks/ by Dr. Richard Cordero, Esq. [email protected] Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr. Chief Judge William K. Sessions, III Presiding Officer U.S. District Court, DVT Judicial Conference of the U.S. Post Office Box 928 c/o Supreme Court of the United States Burlington, VT 05402-0928; tel. (802)951-6350 1 First Street, N.E Chief Judge Anthony J. Scirica Washington, D.C. 20543 rd Public Information Office: (202)479-3211 U.S. Court of Appeals, 3 Cir. Clerk's Office: (202)479-3011 U.S. Courthouse 601 Market Street Mr. Jeffrey P. Minear Philadelphia, PA 19106; tel. (215)597-2399 Administrative Assistant to the Chief Justice Supreme Court of the United States Chief Judge Garrett E. Brown 1 First Street, N.E U.S. District Court, DNJ Washington, D.C. 20543 402 East State St., Rm 2020 Trenton, NJ 08608; tels. (609)989-2009 Mr. James C. Duff Chief Judge Karen J. Williams Conference Secretary and AO Director th Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts U.S. Court of Appeals, 4 Cir. One Columbus Circle, NE 1100 E. Main St., Annex, Ste. 501 Washington, D.C. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents 1 Harris County Courts at Law — Civil 1-1 Court Directory 1-2 Local Rules 1-3:1 Harris County Civil Court at Law No. 2, Hon. Jim F. Kovach 1-3:2 Harris County Civil Court at Law No. 3, Hon. LaShawn A. Williams 1-3:3 Harris County Civil Court at Law No. 4, Hon. William “Bill” McLeod 2 Harris County Courts at Law — Criminal 2-1 Court Directory 2-2 Local Rules 2-3:1 Harris County Criminal Court at Law No. 16, Hon. Darrell Jordan 3 Harris County District Court — Civil 3-1 Court Directory 3-2 Local Rules 3-3:1 Harris County 11th Civil District Court, Hon. Kristen Brauchle Hawkins 3-3:2 Harris County 55th Civil District Court, Hon. Latosha Lewis Payne 3-3:3 Harris County 127th Civil District Court, Hon. R. K. Sandill 3-3:4 Harris County 129th Civil District Court, Hon. Michael Gomez 3-3:5 Harris County 133rd Civil District Court, Hon. Jaclanel Moore McFarland 3-3:6 Harris County 151st Civil District Court (Electronic Court), Hon. Mike Engelhart 3-3:7 Harris County 152nd Civil District Court, Hon. Robert K. Schaffer 3-3:8 Harris County 190th Civil District Court, Hon. Beau A. Miller 3-3:9 Harris County 270th Civil District Court, Hon. Dedra Davis 4 Harris County District Courts — Criminal 4-1 Court Directory 4-2 Local Rules 4-3:1 Harris County 208th Criminal District Court, Hon. Greg Glass 4-3:2 Harris County 337th Criminal District Court, Hon. Herb Ritchie 4-3:3 Harris County 351st Criminal District Court, Hon. -

Dennis Dale Gerami, Et Al. V. Hyperdynamics Corporation, Et Al

US District Court Civil Docket as of September 16, 2015 Retrieved from the court on September 16, 2015 U.S. District Court SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS (Houston) CIVIL DOCKET FOR CASE #: 4:14-cv-00641 Gerami v. Hyperdynamics Corporation et al Date Filed: 03/13/2014 Assigned to: Judge Sim Lake Date Terminated: 09/16/2015 Cause: 28:1331 Fed. Question: Securities Violation Jury Demand: Plaintiff Nature of Suit: 850 Securities/Commodities Jurisdiction: Federal Question Plaintiff Dennis Dale Gerami represented by Francis P McConville Labaton Sucharow LLP 140 Broadway New York, NY 10005 (212) 907-0650 Fax: (212) 883-7550 Email: [email protected] TERMINATED: 04/22/2015 LEAD ATTORNEY ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED Sammy Ford , IV Abraham Watkins Nichols Sorrels Agosto & Friend 800 Commerce St Houston, TX 77002 713-222-7211 Email: [email protected] ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED V. Defendant Hyperdynamics Corporation represented by Samuel Wollin Cooper Paul Hastings LLP 600 Travis Street 58th Floor Houston, TX 77002 713-860-7305 Fax: 713-353-2322 Email: [email protected] LEAD ATTORNEY ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED Christie Ann Mathis Paul Hastings LLP 600 Travis Street 58th Floor Houston, TX 77002 713-860-7348 Fax: 713-353-2349 Email: [email protected] ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED Edward Han Paul Hastings LLP 1117 S. California Ave Palo Alto, CA 94304 650-320-1800 Email: [email protected] PRO HAC VICE ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED Ryan Fawaz Paul Hastings LLP 695 Town Center Drive, 17th Floor Costa Mesa, CA 92626 714-668-6200 Email: [email protected] PRO HAC VICE ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED Defendant Ray Leonard represented by Samuel Wollin Cooper (See above for address) LEAD ATTORNEY ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED Christie Ann Mathis (See above for address) ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED Edward Han (See above for address) PRO HAC VICE ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED Ryan Fawaz (See above for address) PRO HAC VICE ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED Defendant Paul C. -

CIRCUIT COURT of APPEALS Criminal Justice Section Program

SIGNIFICANT DECISIONS OF THE U.S. SUPREME COURT & THE 5TH CIRCUIT COURT OF APPEALS Criminal Justice Section Program Buck Files Bain, Files, Jarrett, Bain & Harrison, P.C. 109 West Ferguson Street Tyler, Texas 75702-7203 (903) 595-3573 Friday, June 11, 2010 3:30 p.m. – 4:00 p.m. F. R. (Buck) Files, Jr. is a shareholder in the firm of Bain, Files, Jarrett, Bain and Harrison, P.C., in Tyler, Texas. He holds board certifications in criminal law from the Texas Board of Legal Specialization and in criminal trial advocacy from the National Board of Trial Advocacy. Buck is a charter member and former director of the Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association. In 2007, he was honored by a resolution of TCDLA’s board of directors for having had more than 100 of his columns – “The Federal Corner” – published in the VOICE for the Defense. Buck is currently serving as a member of the Texas Board of Legal Specialization and as Chair of the State Bar’s Continuing Legal Education Committee. He is a former member of the State Bar’s board of directors and was named “Outstanding Third Year Director” in 2007. He also received a State Bar Presidential Citation for his work as Co-Chair of the State Bar’s Task Force on the Qualifications of Habeas Counsel in Capital Cases. In 2004, he was named the Defense Lawyer of the Year by the Criminal Justice Section of the State Bar. Buck received his B.A. degree from Austin College (1960) and his M.L.A. -

Texas Courthouse Guide 2020

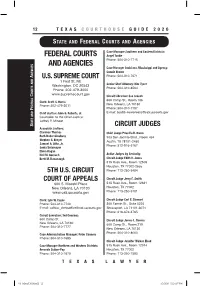

12 TEXAS COURTHOUSE GUIDE 2020 STATE AND FEDERAL COURTS AND AGENCIES Case Manager Southern and Eastern Districts: FEDERAL COURTS Angel Tardie Phone: 504-310-7715 S AND AGENCIES IE Case Manager Louisiana, Mississippi and Agency: C Connie Brown GEN A Phone: 504-310-7671 U.S. SUPREME COURT 1 First St. NE AND Senior Staff Attorney: Kim Tycer S Washington, DC 20543 Phone: 504-310-8504 Phone: 202-479-3000 OURT www.supremecourt.gov C Circuit Librarian: Sue Creech 600 Camp St., Room 106 Clerk: Scott S. Harris Phone: 202-479-3011 New Orleans, LA 70130 EDERAL Phone: 504-310-7797 F Chief Justice: John G. Roberts, Jr. E-mail: [email protected] AND Counselor to the Chief Justice: Jeffrey P. Minear TATE S CIRCUIT JUDGES Associate Justices: Clarence Thomas Chief Judge Priscilla R. Owen Ruth Bader Ginsburg 903 San Jacinto Blvd., Room 434 Stephen G. Breyer Austin, TX 78701-2450 Samuel A. Alito, Jr. Phone: 512-916-5167 Sonia Sotomayor Elena Kagan Neil M. Gorsuch Active Judges by Seniority: Brett M. Kavanaugh Circuit Judge Edith H. Jones 515 Rusk Ave., Room 12505 Houston, TX 77002-2655 5TH U.S. CIRCUIT Phone: 713-250-5484 COURT OF APPEALS Circuit Judge Jerry E. Smith 600 S. Maestri Place 515 Rusk Ave., Room 12621 New Orleans, LA 70130 Houston, TX 77002 www.ca5.uscourts.gov Phone: 713-250-5101 Clerk: Lyle W. Cayce Circuit Judge Carl E. Stewart Phone: 504-310-7700 300 Fannin St., Suite 5226 E-mail: [email protected] Shreveport, LA 71101-3074 Phone: 318-676-3765 Circuit Executive: Ted Cominos 600 Camp St. -

NARRATIVES of the ENRON SCANDAL in 2000S POLITICAL CULTURE

BIG BUSINESS, DEMOCRACY, AND THE AMERICAN WAY: NARRATIVES OF THE ENRON SCANDAL IN 2000s POLITICAL CULTURE Rosalie Genova A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History Chapel Hill 2010 Approved by: Dr. John Kasson Dr. Michael Hunt Dr. Peter Coclanis Dr. Lawrence Grossberg Dr. Benjamin Waterhouse © 2010 Rosalie Genova ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT ROSALIE GENOVA: Big Business, Democracy, and the American Way: Narratives of The Enron Scandal in 2000s Political Culture (Under the Direction of Dr. John Kasson) This study examines narratives of the Enron bankruptcy and their political, cultural and legal ramifications. People’s understandings and renderings of Enron have affected American politics and culture much more than have the company’s actual errors, blunders and lies. Accordingly, this analysis argues that narratives about Enron were, are, and will continue to be more important than any associated “facts.” Central themes of analysis include the legitimacy and accountability of leadership (both governmental and in business); contestation over who does or does not “understand” business, economics, or the law, and the implications thereof; and conceptions of the American way, the American dream, and American civic culture. The study also demonstrates how Enron narratives fit in to longer patterns of American commentary on big business. iii Dedicated to the memory of my father Paul, 1954-2008 the only “Doctor Genova” I have ever known iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To a certain extent, the colleagues who have been making fun of me ever since I developed my dissertation topic are right: this research process has been different, shall we say, from that of most historians.