Baumgartner V. First Church of Christ, Scientist: Religious Healers' Exemption from Liability Rebecca Carlins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Iowa City, Iowa), 1943-08-06

Ration CalenCiar is Slightly Cooler .1\00£,1£0 "(pOPS .tamp. N .•• a •• Q •• ,1,. A. ••• 'I MIAT .I.mp U ••,1 ... A.,. ali ••OCIS8EP 1'0001 .I.... p. _, 8 .na T npl.. 8.pl. lit; GASOLINE A IOWA; Lleht Sbowel'll in west ••• ,. ••••• plr. 11.,1. ~ I i PUIlL OIL p.r. 5 ••• , •••• 'fI- U, •• ,Ire 8e,&. SU; 8UO" ••,_ ._,. III .D. 18, ..... porUon today. SI~hUy eooler ••••1 ... .upl •• 0.1. I I: 8HAIIS lla.. , .1 ..,1 ... 0.1. In extreme liOutbe~ II; 'VaL OIL ,.r. 1 •• U ~ ••', '".''', •• plr. I ••• f,. Iowa City's Morning Newspaper In -FlVECENTS TBI A180ClATID ••1111 IOWA CITY. IOW~~lDAY. AUGUST 6. 1943 TBI AJlSOCIATID P.III VOLUME XlJll NUMBER 267 I Windl~ Ih OfU, Great Allied Victories Around the World ch fotrs IraYell~ ulliver, to send a 1.eh\, ~rn her armed lately:' Ing O.k. I nick, un 're du, IUS(! it e add, d Mrs and ~ lat the Il1pl at Soviets Take C'rel, Be . lg()r~d; Catania Falls 'n M.rs. letter -------------------------------- .--------------~----------~~~-- \Vas of CRACKS APPEAR IMMINENT IN 'FESTUNG EUROPE' In the latters ~Iali~ , ' s 'roops. Allies Surging ' Peace Not. Menti~ned Hall 01 Munda Airdrome Take"; Ie sun: lrward . ' • As,~adogho Cabinet E" : G" which mOUnt. NATtOHI ..HOtI ..._ .. ,. .T~wa,d ,Vital Holds Long.Meeting nllre Jap arrlson Trapped Jcore Greatest IMM"'Nf ~o.... COUA,.. ica tion spiclon Of nALY 41 NATtOHI ANt 'H"'OO' .""" ATJI,JEO ITEADQ ARTER,'] Tnl~ 01 TJJWE,"P PA ~vestl_ AUG _.Y .. '"10 tY I'OeCI Report Conference 01 UNITt. -

L5i1 UNIVERSITY of MINNESOTA UNIVERSITY of MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT of WOMEN's INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS Directory

~ , I l5i1 UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF WOMEN'S INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS Directory Administrative and Support Staff Director Vivian Barfield 373-2253 Fundraising Coordinator Barbara Stowe 373-2481 Sports Information Director Carol Van Dyke 376-5259 Assistant Sports Information Director Tom Byrd 376-5259 Athletic Trainer Leah Wollen burg 376-5039 Assistant Athletic Trainer Dusty Rippelmeyer 376-5039 Event Coordinator Barb Kalvik 376-2566 Business Manager Nancy Adams 373-2255 Administrative Assistant Kathy Surridge 373-2255 Administrative Intern Marlys Schmidt 373-2255 Secretary To The Director Deb Walker 373-2253 Department Secretaries Sharon Blizen 373-2255 Betty Anderson 373-2255 Coaching Staff Tennis Ellie Peden 376-5378 Softball Linda Wells 376-5287 Field Hockey Ruth Christianson 373-5145 Gymnastics Katalin and Gabor Deli 376-3490 Cross Country Mike Lawless 376-5288 Swimming Jean Freeman 373-5145 Diving Frank Oman 373-5145 Golf Bob Kieber 376-5378 Volleyball Linda Wells 376-5287 Basketball Ellen Mosher 376-5435 Track and Field Mike Lawless 376-5288 Central Office Group for the University of Minnesota C. Peter Magrath, President Donald Brown, Vice President for Finance Robert Stein, Vice President for Administration and Planning Frank Wilderson, Vice President for Student Affairs AI Link, Acting Vice President for Academic Affairs Lyle French, Vice President for Health Sciences Stanley Kegler, Vice President for Institutional Relations Board of Regents Charles Casey Charles McGuiggan William Dosland Wenda Moore, Chair Erwin Goldfine Lloyd Peterson Lauris Krenik Mary Schertler Robert Latz Neil Sherburne David Lebedoff Michael Unger Contents Our Message To You ............ .... .. .. ..... ... .... .. .. Page 4 Vivian Barfield-Director .......... ........ .... ....... ................ 5 C. -

The Ann Arbor Register. Vol

THE ANN ARBOR REGISTER. VOL. XVII. NO. 9. ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 26, 1891. WHOLE NO. 844. his love of nature and the natural bent RESULT OF MAYOR'S BALLOT. THE LAST SAD RITES. ami grasp of his mind all irresistibly PUBLIC OPINION OUR 25 CENT COLUMN. turned him. With a reverent but master [Hereafter no signature will be required hand he endeavored to lift the veil of EXPRESSES ITSELF OX SEVERAL on the ballots. Thus the identity of the voter Adveitisements, such as To Rent, For Sale FUNERAL. SERVICES AND RESO- will not be known to any one. Every one LUTIONS. the past, to follow the sleps of creation, MATTERS. ' and Wants, not exceeding three lines, can be ascertain its laws and follow its evolu- may vote anonymously if he so desires.] inserted three weeks for 23 cents. tion. These were the problems to Have We a free Hail Delivery?—Some- The total vote up to Wednesday The University Senate Drafts an Ap- which he delighted to devote himself. evening was as follows: WANTF.K. His other studies were only incidental thing Farther about the Saloons— propriate Memorial Rehearsing the A Correspondent Indulsres lu a "Non E. F. Mills 80 Virtues and Achievements of Prof- to these or to the duties of instruction. J. T. Jacobs 27 A JTTED—Nurse Girl, and to help with house It was under the inspiration of these Seqnitur Argument on the Tariff. Wm. Biggs 14 Wwork. Apply at 35 E. Ann St. 46 LAST CALL! Winchell. grand problems that his most influential A number—in fact a large proportion 8. -

ANNUAL REPORT EDITION N 2011–2012 in Review N Class Notes N Donor Honor Roll a Message from the Chief Administrator

Family TimesF A L L 2 0 1 2 ANNUAL REPORT EDITION n 2011–2012 in Review n Class Notes n Donor Honor Roll A Message From the Chief Administrator Driven By Our Vision Greetings from Holy Family Catholic Schools! Holy Family Catholic Schools As I reflect on my first year as chief administrator, I’m pleased to look back at a year 2011–2012 filled with major accomplishments for our system. I invite you to take a few minutes to review this annual report, a compilation of our 2011–2012 highlights and Carol Trueg Chief Administrator a reflection of the hard work and generosity of our staff, students, parents and Catholic community. Board of Education While I’m very proud of all of our accomplishments, I’m not satisfied. My mother’s Arnie Honkamp St. Columbkille Parish constant refrain as we were growing up was, “Whatever is worth doing is worth doing Board President well,” and that statement continues to drive me to find ways we can better deliver an Tom Flogel outstanding Catholic education to the students who walk through our doors each day. St. Joseph Key West Parish Board Vice President Julie Neebel To that end, we are now one year into the ambitious goal I set at the start of the At-Large | St. Joseph the Worker Parish 2011–2012 school year: make Holy Family the top academic system in the state of Board Secretary Carol Gebhart Iowa within five years, while ensuring that the Catholic faith is at the center of all Holy Spirit Pastorate that we do. -

A Mother's Perspective

ccaquarterly newsletter of the children’snetwork craniofacial association Cher — honorary chairperson spring 2011 inside cca kid camryn berry . 2 cca adult beth wenger . 3 cca supersib caleb berry . .4 rick’s raffle . 5 calendar of events . 6 craniofacial acceptance message month . .6 from the financial assistance . .6 henry’s march . .7 chairman fresh start . .8 t is an honor to write this testimonial . .12 ias the newly elected chair of the Children’s Craniofacial donors in the spotlight . .12 a mother’s Association Board of good news . .13 perspective Directors . If you’re reading a cca mugshot . 13 CCA newsletter for the first By Lisa Moore links of love . .13 time, my hope is that you will e moved to Tampa when I was 8 months pregnant want to seek a relationship fundraising news . 5,7 & 13 wwith Katie . I was polyhydric (extra amniotic fluid), with CCA and become a part prosthetic devices . 14-15 and they were concerned that her head was measuring of our wonderful family . If charitable ira rollover . .16 larger than her age . At the follow-up ultrasound they you’re a regular reader and also took note of her feet and toes . I knew in my heart already a part of the CCA donor lists . 16-19 something was wrong . Without knowing what we would family, thank you for your 3 cheers for volunteers . .20 be facing at her birth, Tom and I were blessed with an 8 lb continued involvement and 9oz baby girl with Pfeiffer’s syndrome . support . I hope your needs We thought we were very fortunate there was a doctor are being met and that you coming out of the OR who noticed Katie immediately and are motivated to remain a told my husband that she had a craniofacial syndrome . -

The Power of Societal Reimaging and Advertising in the All American Girls Professional Baseball League

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2017 Creating a Female Athlete: The oP wer of Societal Reimaging and Advertising in the All American Girls Professional Baseball League Kaitlyn M. Haines [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons, Sports Studies Commons, United States History Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Haines, Kaitlyn M., "Creating a Female Athlete: The oP wer of Societal Reimaging and Advertising in the All American Girls Professional Baseball League" (2017). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. 1089. http://mds.marshall.edu/etd/1089 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. CREATING A FEMALE ATHLETE: THE POWER OF SOCIETAL REIMAGING AND ADVERTISING IN THE ALL AMERICAN GIRLS PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL LEAGUE A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History by Kaitlyn M. Haines Approved by Dr. Kathie D. Williams, Committee Chairperson Dr. Margaret Rensenbrink Dr. Montserrat Miller Marshall University July 2017 ii © 2017 Kaitlyn Michelle Haines ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii DEDICATION To my baseball family, who taught me to believe in my future. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express sincere appreciation to the faculty of the Department of History for their wonderful support. -

Sport & Celebr T & Celebr T & Celebr T

SporSportt && CelebrCelebrityity MemorMemorabiliaabilia inventory listing ** WE MAINLY JUST COLLECT & BUY ** BUT WILL ENTERTAIN OFFERS FOR ITEMS YOU’RE INTERESTED IN Please call or write: PO Box 494314 Port Charlotte, FL 33949 (941) 624-2254 As of: Aug 11, 2014 Cord Coslor :: private collection Index and directory of catalog contents PHOTOS 3 actors 72 signed Archive News magazines 3 authors 72 baseball players 3 cartoonists/artists 74 minor-league baseball 10 astronaughts 74 football players 11 boxers 74 basketball players 13 hockey players 74 sports officials & referrees 15 musicians 37 fighters: boxers, MMA, etc. 15 professional wrestlers 37 golf 15 track stars 37 auto racing 15 golfers 37 track & field 15 politicians 37 tennis 15 others 37 volleyball 15 “cut” signatures: from envelopes... 37 hockey 15 CARDS 76 soccer 16 gymnastics & other Olympics 16 minor league baseball cards 76 music 16 major league baseball cards 82 actors & models 19 basketball cards 97 other notable personalities 20 football cards 97 astronaughts 21 women’s pro baseball 98 politician’s photos 21 track, volleyball, etc., cards 99 signed artwork 24 racing cards 99 signed business cards 25 pro ‘rasslers’ 99 signed books, comics, etc. 25 golfers 99 other signed items 26 boxers 99 cancelled checks 27 hockey cards 99 baseball lineup cards 28 politicians 100 newspaper articles 28 musicians/singers 100 cachet envelopes 29 actors/actresses 100 computer-related items 29 others 100 other items- unsigned 29 LETTERS 102 uniforms & jerseys, etc. 30 major league baseball 102 PLATTERS MUSIC GROUP (ALL ITEMS) 31 minor league baseball 104 MULTIPLE SIGNATURES, 36 umpires 105 BALLS, PROGRAMS, ETC. -

Cumulative Lifetime Giving

Marla Troughton* Farm Bureau Insurance Red Roof Inn Carl & Judy Barton TV 49 David & Rebecca Farris* Richard & Valerie Ribeiro Richard & Alice Batson Ubiquitel Inc. Melanie Files Jim & Patricia Richardson Batson Development Company Inc. Wal-Mart Marie H. Flood* Jim & Sharon Ridenhour* Baxter International Foundation James L. Walker Estate Gannett Foundation Inc. Sal & Patricia Rinella William & Katherine Beach Robert & Mary Emma Welch David Gibbs Riner Wholesale Bellsouth Telecommunications Lorraine Wilson Wendell & Jean Gilbert Mitch & Jenny Robinson* Eric & Elaine Berg* James & Glema Withrow* Tony Gilmore* James Roe* Best Western Plus Gish Sherwood and Friends Inc. Ann Ross Beta Sigma Phi The Austin Peay Society Associates Anne Glass* John & Janet Rudolph* Michael Betts ($25,000 to $49,999) Golden Eagle Jewelry Rare Coins Rufus Johnson Associates of Margaret Bibb Active Screen Graphics LLC and Metals Clarksville Inc. Bikers Who Care Inc. CUMULATIVE LIFETIME GIVING Ajax Distributing Company Graftech International James Russell William & Lisa Blair George Albright Estate Mark & Camie Green* Len & Melessa Rye* Bojangles The Austin Peay Society Heritage Chattanooga Avo & James Woodall Taylor Estate HAM Broadcasting Company Inc. Altra Federal Credit Union Lee Greenwood Bryce & Jody Sanders* Charles & Carol Bond* ($1,000,000 or more) The Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee Orthopaedic Alliance Richard D. Hardwick Revocable Trust America's Best LLC Ed Groves Jim Schacht Inc. Roy N. Bordes Anonymous Tennessee Tennova Healthcare Amelia Lay Hodges Estate James Amos, Jr. Matthew & Kelley Guth* Scientific-Atlanta Inc. Demetra Boyd* Larry & Vivian Carroll James & Betty Corlew, Sr. Joseph & Marjorie Trahern, Jr.* James G. & Christa Holleman* Jim & Jo Amos Sears & Paula Hallett* Gary & Becky Scott* Lillian Bradley Clarksville-Montgomery County R N Crum Estate Trane Foundation J.D. -

Donor Insert Fall 2010

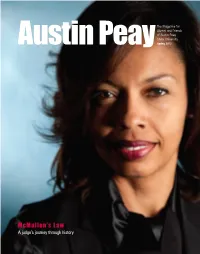

The Magazine for Alumni and Friends of Austin Peay State University Austin Peay Spring 2012 McMullen’s Law A judge’s journey through history FEATURES McMullen’s Law Camille Reese McMullen’s (‘93) journey from APSU to South Africa to being named Tennessee’s first African- American female appellate court judge. Page 10 Albert’s Man Meet Todd Perry (‘86), the man in charge of baseball great Albert Pujols’ charitable foundation. Page 20 The New APSU Recent and upcoming building projects give the campus a new look. Page 30 Sections APSU Headlines ..................................... .2 Alumni News and Events ...................16 Faculty Accomplishments ................. 18 Sports News ......................................... 26 Class Notes ............................................ 36 Cover Tennessee appellate court Judge Camille Reese McMullen (‘93). Photo by Beth Liggett Inside Photo Austin Peay State University unveiled its new military coin in December 2011 during a ceremony honoring active duty and military veteran graduates. For more about the coin, please see the story on Page 36. Photo by Beth Liggett AUSTIN PEAY Reader’s Guide Austin Peay is published biannually—fall and spring— by the Office of Public Relations and Marketing. Press run for this issue is 40,000. Bill Persinger (’91) Editor Melony Shemberger (’06), Ed.D. Assistant Editor Charles Booth (‘10) Feature Writer Kim Balevre (’08) Graphic Designer Rollow Welch (’86) Graphic Designer Beth Liggett Photographer Michele Tyndall (’06, ’09) Production Manager Nikki Peterson -

Tar 1984 CE TRAL OFFICE HOME-Pi Beta Phi's New Official Resi Dence Occupies Much of the Second Roor of This New Office Building in St

tar 1984 CE TRAL OFFICE HOME-Pi Beta Phi's new official resI dence occupies much of the second Roor of this new office building in St. Louis. Pi Phi quarters cover approximately 2,200 square feet. The new offices and work areas contained in that area were set up to meet the fraternity's needs as the build ing was being completed. Actually the building is located in Clayton, a St. Louis suburb. Pi Beta Phi members in the area or those passing through are invited to visit the new facility. Tit. Cover-CHEEI WOI the hollmaric of Ihi. happy qrxnt.t through the foil in 51 . Loui • . Th.ir Imil ••• how they were full of it and thei, p.p k'pl fan readion rollin, at both Washington Univ.nity ortd St. louis Cardinal foot ball gomel. MiIJouri •• to Ili Phi, all, th.y aN Juli. W... el , Susan SIHhr, Nancy "aton and Kim Monch.l. THE Arrow OF PI BETA PHI VOLUME 81 WINTER 1964 NUMBER 2 OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE PI BETA PHI FRATERNITY 1867 O{jiu 0/ Pllbliralion: 112 S. Hanley Rd., St. Louis, Mo. 631O~ ARROW Editorial , ....... ". , .... 2 STAFF Off Ihe ARROW Hook ............ , ... Whal Central Office Does for You. ,.... 4 The George Starr Lasher Living Legacy , , 9 A,.,oul Editor: DoROTHY DAVIS STUCK (Mrs. Howard c., Jr.), Box 490, Marked Tree, Their Honors Honor Pi Beta Phi, ,., . .. 10 Ark. 7236) News From Little Pigeon .. , ....... , . , . 20 From Pi Phi Pens ............... ,.... 21 Alunm~ CINb Edilor: ADELE ALFORD HEINK, 3434 Jewell St., San Diego, Calif. 92109 Feature Section .. -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1943-05-02

, III -. .... Ration Calendar Cooler OAS ·'A" ,.aupon~ n aspire .... , Ih eor FEE tuu,HJll 29 ex-Jjtre Atll)' 8UI 8LOAB euupOD J2 t::r.,.lru May Iii: JOWA: Cooler Ihls dlenlOon: Red 'E meal .. tamps expire ay !U. fresh to stronr 0, n. and J IIlJmp.. ex-plte May :11: THE DAILY IOWAN 8110£8 eOllpoo J'2 explrel JuneU. winds, Iowa Cit y '. s M 0 r n i n? New s p a per FIVE CENTS THE ASSOCIATID ral811 IOWA em, IOWA SUNDAY, MAY 2, 1943 TBI A SOClATED rltllSS VOLVME XIJn NUMBER 186 STRIKING COAL MINERS PASS TIME ayonet ttac • • .. Two trategic XIS I S 48-Hour Steel Second ·Bond Drive RAF Pounds Government Begins , , Will Top U.S. Quota Allied Airmen Strike War~s f Operation of Nation's Week Ordered Total Will Amount Essen, Harbor Strike-Bound Mines Most Deadly ·Blow at Shipping To 4 Billion More WASHINGTON (AP) - Man- LONDON (AP)-Roya I Air R' C I . N ""'rce pounded the Ger- 00 By EDWARD KENNEDY po\yer CommiSSIoner Me utt de- Than Amount Set r u bombe~.~ estnctions on ~ man indlJstrial city M Essen F'rl- Consumption, Travel .A LLJED IIE.\DQ ARTER IN NORTH AFRICA (AP) creed tonight that steel · mills WASHINGTON (AP) _ Wit h day night and Berlin said Ameri- American Roldil'I'R in theil' first lal'gl'·scale bayonet attack of the working less than 48 hours a week sales fOI' two of the [inal three Can four-engined heavyweights By Railway Expected 'l'unisian campaign ha'" lllbbcd into the fl'in~e of the fan·. -

Baumgartner Gives Graduates “Four Keys to Success” Sonia Rosado

DULLETIN (UPC VOL. 11, NO. 4 WILLIAM PATERSON COLLEGE FEBRUARY 17, 1997 Baumgartner Gives Graduates “ Four Sonia Rosado Keys to Success” Named Trustee Ice and piercing cold failed to graduates, their families, and his Sonia Rosado, who came to the interfere with the joy and excitement mother Lois Baumgartner, who has United States from of the 649 undergraduates and 81 worked at WPC since 1967, “was Puerto Rico when graduate students who received their carrying the flag in Atlanta in 1996.” she was 12 years degrees at the college’s second winter He urged the graduates to feel pride in old, and became a commencement on January 19. their accomplishment as well. leader in Paterson More than 4,000 parents and Anne Li, president of the Class of educational and visitors jammed the bleachers in the 1997, thanked the faculty for their political circles, Rec Center to cheer, take pictures and dedication to the students, the has been appointed shed tears of happiness as the gradu— Blanchard families for their support and to the Board of B|ll ates walked to the stage to receive unconditonal love for their respective Trustees. Sonia Rosado their diplomas when their names were graduates, and the graduates for their Confirmed by the New Jersey State announced over the loudspeakers. “perseverance, desire, excellence, Senate, she was selected for a six—year Responding to the celebratory intelligence and pride which you will term by Governor Christine Todd atmosphere, Olympic gold medal need to achieve and succeed in today’s Whitman. (Continued on page 3) winner Bruce Baumgartner told the society.” graduates that “success is doing the President Arnold Speert reflected best you can do.” The four keys, he n “this rite of passage, this gradua~ Roland Watts Takes Over said, are “to set your goals high, to tion ceremony, (which) marks the Student Development surround yourself with good people, finishing of all degree requirements Roland Watts has been named acting take care of your body, and work hard.