ADMINISTRATIVE JUSTICE in EUROPE INTRODUCTION (History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Code of Administrative Justice

Code of Administrative Justice Legislative Part Preliminary Title Article L1 This code applies to the Council of State and to administrative tribunals and administrative courts of appeal. Article L2 Judgments are rendered in the name of the French people. Article L3 Judgments are rendered by judges acting as a collegial body, unless the law provides otherwise. Article L4 Applications do not cause proceedings to be suspended, unless the court orders otherwise, or unless there are special statutory provisions. Article L5 Both parties are represented in the preparation of the case. Certain requirements flow from the fact that both parties are represented; if the case is urgent, these former requirements will be adapted to those of the urgent situation. Article L6 Hearings are held in open court. Article L7 A member of the court, appointed to act as consultant judge, presents his or her opinion, in public and with total independence, on the issues that must be decided by the court, that arise from the applications or appeals, and on the possible solutions. Article L8 Text last revised 3 October 2013 - Document generated 11 November 2013 - The judges' deliberations are secret. Article L9 The judges must give reasons for their judgments. Article L10 Judgments are rendered in public. Judgments must mention the names of the judges by whom they were rendered. Article L11 Judgments are enforceable. Text last revised 3 October 2013 - Document generated 11 November 2013 - Legislative Part Book I: The Council of State Title I – Powers Chapter I: Powers in contentious matters Article L111-1 The Council of State is the highest administrative court. -

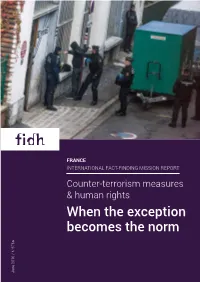

Counter-Terrorism Measures and Human Rights: When the Exception

FRANCE INTERNATIONAL FACT-FINDING MISSION REPORT Counter-terrorism measures & human rights When the exception becomes the norm June 2016 / N°676a TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 I. THE STATE OF EMERGENCY UNDER SCRUTINY 6 A. Factual background 6 1. Measures implemented under the state of emergency 7 2. Searches and house arrests: facts and figures 8 3. Parliamentary oversight 10 4. Judicial oversight 11 B. Analysis of consequences and assessment of oversight mechanisms 16 1. The consequences of state of emergency measures 16 2. Questioning the efficacy of state of emergency measures 19 3. What kind of safeguards are in place? 22 II. WHEN THE EXCEPTION BECOMES THE NORM: THE SHARP INCREASE IN COUNTER-TERRORISM LEGISLATION 27 1. The Law of 24 July 2015: intelligence 28 2. Draft reforms to French criminal procedure, another reason for concern 29 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 33 ANNEX 1 : INSTITUTIONS AND PERSONS INTERVIEWED 40 ANNEX 2 : LETTER FROM THE INTERIOR MINISTER BERNARD CAZENEUVE, IN RESPONSE TO MEETING REQUEST BY THE FIDH DELEGATION 41 En couverture : Fouille intervenue dans le cadre d’une opération de police effectuée le 27 novembre 2015 au matin dans un squat au Pré Saint Gervais, occupé par des personnes suspectées de « trouble à l’ordre public pendant la COP21 », selon des sources policières. © AFP PHOTO / LAURENT EMMANUEL 2 FIDH – France - Counter-terrorism measures & human rights FIDH – France - Counter-terrorism measures & human rights 3 INTRODUCTION In the weeks following the attacks, the government also presented to Parliament draft legislation seeking to modify French criminal procedure, adapting it to address such exceptional situations. -

Criminal Proceedings and Defence Rights in France

CRIMINAL PROCEEDINGS AND DEFENCE RIGHTS IN FRANCE This leaflet covers: Information about FTI Definitions of key legal terms Criminal proceedings and defence rights in France Useful links This booklet was last updated in February 2013 About Fair Trials International Since 1992 Fair Trial International has worked for the better protection of fair trial rights and defended the rights of people facing criminal charges in a country other than their own. Our vision is a world where every person’s right to a fair trial is respected, whatever their nationality, wherever they are accused. Fair Trials International was established to help people arrested outside their own country to defend their right to a fair trial. Every year we help hundreds of people and their families to navigate a foreign legal system by offering practical advice, including contacts of local lawyers; guidance on key issues encountered by people arrested abroad; and basic information on different legal systems and local sources of support. As a charity, we do not charge for any of the assistance that we provide. We believe that respect for fundamental rights and the rule of law are the hallmarks of a just society and that the right to a fair trial is at the heart of this. Sadly too many shocking cases of injustice demonstrate how, time and again, this most basic human right is being abused. We fight against injustice by lobbying for the legal reforms needed to ensure that the right to a fair trial is respected in practice. Working with our clients and international networks, we also campaign for changes to criminal justice laws which are being abused and overused. -

1997 Human Rights Report: France Page 1 of 12

1997 Human Rights Report: France Page 1 of 12 The State Department web site below is a permanent electro information released prior to January 20, 2001. Please see w material released since President George W. Bush took offic This site is not updated so external links may no longer func us with any questions about finding information. NOTE: External links to other Internet sites should not be co endorsement of the views contained therein. U.S. Department of State France Report on Human Rights Practices for 1997 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, January 30, 1998. FRANCE France is a constitutional democracy with a directly elected president and National Assembly and an independent judiciary. The law enforcement and internal security apparatus consists of the Gendarmerie, the national police, and municipal police forces in major cities, all of which are under effective civilian control. The highly developed, diversified, and primarily market-based economy provides residents with a high standard of living. The Government respected the human rights of its citizens, and the law and judiciary provide a means of dealing with individual instances of abuse. Long delays in bringing cases to trial and lengthy pretrial detention are problems. Racially motivated attacks by extremists declined sharply from 480 in 1995 to 195 in 1996. The Government has taken important steps to deal with violence against women and children. Women continue to face wage discrimination. Although no killings occurred in Corsica during the year, there were over 200 bombings, many of which were politically motivated RESPECT FOR HUMAN RIGHTS Section 1 Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom From: http://www.state.gov/www/global/human_rights/1997_hrp_report/france.html 1/13/03 1997 Human Rights Report: France Page 2 of 12 a. -

France 2020 Human Rights Report

FRANCE 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY France is a multiparty constitutional democracy. Voters directly elect the president of the republic to a five-year term. President Emmanuel Macron was elected in 2017. An electoral college elects members of the bicameral parliament’s upper house (Senate), and voters directly elect members of the lower house (National Assembly). Observers considered the 2017 presidential and separate National Assembly elections to have been free and fair. Under the direction of the Ministry of the Interior, a civilian national police force and gendarmerie units maintain internal security. In conjunction with specific gendarmerie units used for military operations, the army is responsible for external security under the Ministry of Defense. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security forces. Members of the security forces committed some abuses. Significant human rights issues included: violence against journalists; criminal defamation laws; and societal acts of violence and threats of violence against Jews, migrants and members of ethnic minorities, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex persons. The government took steps to investigate, prosecute, and punish officials who committed human rights abuses. Impunity was not widespread. Note: The country includes 11 overseas administrative divisions covered in this report. Five overseas territories, in French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Mayotte, and La Reunion, have the same political status as the 13 regions and 96 departments on the mainland. Five divisions are overseas “collectivities”: French Polynesia, Saint-Barthelemy, Saint-Martin, Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, and Wallis and Futuna. New Caledonia is a special overseas collectivity with a unique, semiautonomous status between that of an independent country and an overseas department. -

France's Constitution of 1958 with Amendments Through 2008

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:28 constituteproject.org France's Constitution of 1958 with Amendments through 2008 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:28 Table of contents Preamble . 3 Title I: ON SOVEREIGNTY . 3 Title II: THE PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC . 4 Title III: THE GOVERNMENT . 8 Title IV: PARLIAMENT . 9 Title V: ON RELATIONS BETWEEN PARLIAMENT AND THE GOVERNMENT . 11 Title VI: ON TREATIES AND INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS . 17 Title VII: THE CONSTITUTIONAL COUNCIL . 19 Title VIII: ON JUDICIAL AUTHORITY . 20 Title IX: THE HIGH COURT . 22 Title X: ON THE CRIMINAL LIABILITY OF THE GOVERNMENT . 22 Title XI: THE ECONOMIC, SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL COUNCIL . 23 Title XI-A: THE DEFENDER OF RIGHTS . 24 Title XII: ON TERRITORIAL COMMUNITIES . 24 Title XIII: TRANSITIONAL PROVISIONS PERTAINING TO NEW CALEDONIA . 28 Title XIV: ON THE FRENCH-SPEAKING WORLD AND ON ASSOCIATION AGREEMENTS . 29 Title XV: ON THE EUROPEAN UNION . 29 Title XVI: ON AMENDMENTS TO THE CONSTITUTION . 31 Title XVII . 31 DECLARATION OF HUMAN AND CIVIC RIGHTS OF 26 AUGUST 1789 . 31 PREAMBLE TO THE CONSTITUTION OF 27 OCTOBER 1946 . 34 CHARTER FOR THE ENVIRONMENT . 35 France 1958 (rev. 2008) Page 2 constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:28 Preamble The French people solemnly proclaim their attachment to the Rights of Man and the principles of national sovereignty as defined by the Declaration of 1789, confirmed and complemented by the Preamble to the Constitution of 1946, and to the rights and duties as defined in the Charter for the Environment of 2004. -

Penal Code Penal Code

PENAL CODE PENAL CODE With the participation of John Rason SPENCER QC Professor of Law, University of Cambridge Fellow of Selwyn College FIRST PART ENACTED PARTS Articles 111-1 to 727-2 BOOK I GENERAL PROVISIONS Articles 111-1 to 133-1 TITLE I THE CRIMINAL LAW Articles 111-1 to 113-1 CHAPTER I GENERAL PRINCIPLES Articles 111-1 to 111-5 ARTICLE 111-1 Criminal offences are categorised as according to their seriousness as felonies, misdemeanours or petty offences. ARTICLE 111-2 Statute defines felonies and misdemeanours and determines the penalties applicable to their perpetrators. Regulations define petty offences and determine the penalties applicable to those who commit them, within the limits and according to the distinctions established by law. ARTICLE 111-3 No one may be punished for a felony or for a misdemeanour whose ingredients are not defined by statute, nor for a petty offence whose ingredients are not defined by a regulation. No one may be punished by a penalty which is not provided for by the statute, if the offence is a felony or a misdemeanour, or by a regulation, if the offence is a petty offence. ARTICLE 111-4 Criminal legislation is to be construed strictly. ARTICLE 111-5 Criminal courts have jurisdiction to interpret administrative decisions of a regulatory or individual nature, and to appreciate their legality where the solution to the criminal case they are handling depends upon such examination. CHAPTER II OF THE OPERATIVE PERIOD OF A CRIMINAL LAW Articles 112-1 to 112-4 ARTICLE 112-1 Conduct is punishable only where it constituted a criminal offence at the time when it took place. -

Decree Implementing Act Relating to the Election of The

DECREE IMPLEMENTING ACT 62-1292 OF 6 NOVEMBER 1962 RELATING TO THE ELECTION OF THE PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC BY UNIVERSAL SUFFRAGE Decree 2001-213 of 8 March 2001 (As amended by Decree 2002-243 of 21 February 2002) Section I All French nationals registered on one of the electoral rolls of the Metropolis, the Overseas Departments, French Polynesia, the Wallis and Futuna Islands, New Caledonia, Mayotte or Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon shall take part in the election of the President of the Republic. TITLE I DECLARATIONS AND CANDIDATURES Section 2 Nominations for the election of the President of the Republic shall be presented to the Constitutional Council following the publication of the Decree announcing the election and must reach it no later than midnight on the nineteenth day preceding the first ballot. However, nominations may be presented within the same time-limit: 1. – In the overseas departments, French Polynesia, the Wallis and Futuna Islands, New Caledonia, Mayotte and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, to the Represen- tative of the State; 2. – By elected members of the Higher Council of French Citizens Residing Abroad, to the Head of the Diplomatic or Consular Representation responsible for the consular district where the author of the nomination resides. The Representative of the State or the Head of the Diplomatic or Consular Representation shall ensure that the Constitutional Council is notified of nominations by the most rapid means possible after they have received them. Section 3 Nominations shall be made on forms printed by the administration in accordance with the model adopted by the Constitutional Council. -

Paul De Deckker and Jean-Yves Faberon (Editors)

a th Paul de Deckker and Jean-Yves Faberon (editors) Asia Pacific Press at The Australian National University © Asia Pacific Press 2001 Published by Asia Pacific Press at the Australian National University. This work is copyright. Apart from those uses which may be permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 as amended, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publishers. The views expressed in this book are those of the authors and not necessarily of the publishers. Asia Pacific Press Asia Pacific School of Economics and Management The Australian National Unversity Canberra ACT 0200 Ph: 61-2-6249 4700 Fax: 61-2-6257 2886 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.asiapacificpress.com National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry ISBN 0 7315 3661 4 1. Customary law -Australasia. 2. Customary law - Oceania. I. Faberon, Jean-Yves. II. de Deckker, Paul. 305.8994 Translation by Tim Curtis of the original French publication: Coutume Autochtone et Evolution du Droit dans le Pacifique Sud, Universite franc,;aise,(Editions) L'Harmattan, Paris, 1995 (ISBN 2 7384 3469 X) Production: Asia Pacific Press (Matthew May, Tracey Hansen) Cover design: Annie di Nallo Design Cover photo: Peter Hendrie, Pacific Journeys, Melbourne Printed in Australia by Southwood Press Contents Contributors vii Abbreviations viii Preface ix Custom and the law Norbert Rau/and Part One The position of indigenous custom in the rules applying to the French Overseas Territories 2 Legal adaptations to local sociological -

The Constitutional and Judicial Organization of France and Germany and Some Comparisons of the Civil Law and Common Law Systems

Indiana Law Journal Volume 37 Issue 1 Article 1 Fall 1961 The Constitutional and Judicial Organization of France and Germany and Some Comparisons of the Civil Law and Common Law Systems Joseph Dainow Louisiana State University Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Civil Law Commons, Common Law Commons, and the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation Dainow, Joseph (1961) "The Constitutional and Judicial Organization of France and Germany and Some Comparisons of the Civil Law and Common Law Systems," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 37 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol37/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INDIANA LAW JOURNAL Volume 37 FALL 1961 Number I THE CONSTITUTIONAL AND JUDICIAL ORGANIZATION OF FRANCE AND GERMANY AND SOME COMPARISONS OF THE CIVIL LAW AND COMMON LAW SYSTEMS* JOSEPH DAINoWt In the civil law group of the so-called Romanist legal systems, two of the most significant are the French and German. Although the con- stitutional and judicial organization of these two countries may not be immediately characterized as typically civilian for comparative law studies, an understanding of their composition and function is in some measure an essential part of the background that gives meaning to the civil law in contrast with the common law. -

Phase 3 Report on Implementing the Oecd Anti-Bribery Convention in France

PHASE 3 REPORT ON IMPLEMENTING THE OECD ANTI-BRIBERY CONVENTION IN FRANCE October 2012 This Phase 3 Report on France by the OECD Working Group on Bribery evaluates and makes recommendations on France’s implementation of the OECD Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions and the 2009 Recommendation of the Council for Further Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions. It was adopted by the Working Group on 12 October 2012. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................. 5 A. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 7 1. The on-site visit .................................................................................................................................... 7 2. Outline of the report.............................................................................................................................. 8 3. Progress since the on-site visit .............................................................................................................. 8 4. Economic situation .............................................................................................................................. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 24 March 2015 English Original: French

United Nations A/AC.109/2015/16 General Assembly Distr.: General 24 March 2015 English Original: French Special Committee on the Situation with regard to the Implementation of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples French Polynesia Working paper prepared by the Secretariat Contents Page The Territory at a glance ......................................................... 3 I. Constitutional, political and legal issues ............................................ 5 II. Economic conditions ............................................................ 8 A. General ................................................................... 8 B. Agriculture, fisheries, aquaculture and pearl farming ............................. 8 C. Industry .................................................................. 9 D. Transport and communications ............................................... 9 E. Tourism .................................................................. 10 F. Environment .............................................................. 10 III. Social conditions ............................................................... 11 A. General ................................................................... 11 B. Employment .............................................................. 11 C. Education ................................................................. 12 D. Health care ................................................................ 13 Note: The information contained in the present working