Tahitian Courts in Tahiti and Its Dependencies : 1842-1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Code of Administrative Justice

Code of Administrative Justice Legislative Part Preliminary Title Article L1 This code applies to the Council of State and to administrative tribunals and administrative courts of appeal. Article L2 Judgments are rendered in the name of the French people. Article L3 Judgments are rendered by judges acting as a collegial body, unless the law provides otherwise. Article L4 Applications do not cause proceedings to be suspended, unless the court orders otherwise, or unless there are special statutory provisions. Article L5 Both parties are represented in the preparation of the case. Certain requirements flow from the fact that both parties are represented; if the case is urgent, these former requirements will be adapted to those of the urgent situation. Article L6 Hearings are held in open court. Article L7 A member of the court, appointed to act as consultant judge, presents his or her opinion, in public and with total independence, on the issues that must be decided by the court, that arise from the applications or appeals, and on the possible solutions. Article L8 Text last revised 3 October 2013 - Document generated 11 November 2013 - The judges' deliberations are secret. Article L9 The judges must give reasons for their judgments. Article L10 Judgments are rendered in public. Judgments must mention the names of the judges by whom they were rendered. Article L11 Judgments are enforceable. Text last revised 3 October 2013 - Document generated 11 November 2013 - Legislative Part Book I: The Council of State Title I – Powers Chapter I: Powers in contentious matters Article L111-1 The Council of State is the highest administrative court. -

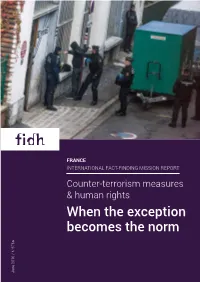

Counter-Terrorism Measures and Human Rights: When the Exception

FRANCE INTERNATIONAL FACT-FINDING MISSION REPORT Counter-terrorism measures & human rights When the exception becomes the norm June 2016 / N°676a TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 I. THE STATE OF EMERGENCY UNDER SCRUTINY 6 A. Factual background 6 1. Measures implemented under the state of emergency 7 2. Searches and house arrests: facts and figures 8 3. Parliamentary oversight 10 4. Judicial oversight 11 B. Analysis of consequences and assessment of oversight mechanisms 16 1. The consequences of state of emergency measures 16 2. Questioning the efficacy of state of emergency measures 19 3. What kind of safeguards are in place? 22 II. WHEN THE EXCEPTION BECOMES THE NORM: THE SHARP INCREASE IN COUNTER-TERRORISM LEGISLATION 27 1. The Law of 24 July 2015: intelligence 28 2. Draft reforms to French criminal procedure, another reason for concern 29 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 33 ANNEX 1 : INSTITUTIONS AND PERSONS INTERVIEWED 40 ANNEX 2 : LETTER FROM THE INTERIOR MINISTER BERNARD CAZENEUVE, IN RESPONSE TO MEETING REQUEST BY THE FIDH DELEGATION 41 En couverture : Fouille intervenue dans le cadre d’une opération de police effectuée le 27 novembre 2015 au matin dans un squat au Pré Saint Gervais, occupé par des personnes suspectées de « trouble à l’ordre public pendant la COP21 », selon des sources policières. © AFP PHOTO / LAURENT EMMANUEL 2 FIDH – France - Counter-terrorism measures & human rights FIDH – France - Counter-terrorism measures & human rights 3 INTRODUCTION In the weeks following the attacks, the government also presented to Parliament draft legislation seeking to modify French criminal procedure, adapting it to address such exceptional situations. -

Political Reviews

Political Reviews 0LFURQHVLDLQ5HYLHZ,VVXHVDQG(YHQWV-XO\ WR-XQH david w kupferman, kelly g marsh, donald r shuster, tyrone j taitano 3RO\QHVLDLQ5HYLHZ,VVXHVDQG(YHQWV-XO\ WR-XQH lorenz gonschor, hapakuke pierre leleivai, margaret mutu, forrest wade young 7KH&RQWHPSRUDU\3DFL²F9ROXPH1XPEHU¥ E\8QLYHUVLW\RI+DZDL©L3UHVV 127 3RO\QHVLDLQ5HYLHZ,VVXHVDQG(YHQWV -XO\WR-XQH 5HYLHZVRI$PHULFDQ6ëPRD&RRN controversies over two projects of the Islands, Hawai‘i, Niue, Tokelau, new government: a bill to reform the Tonga, and Tuvalu are not included country’s land legislation and a reso- in this issue. lution to reinscribe the territory on the United Nations List of Non-Self- French Polynesia Governing Territories (nsgts). During the period under review, politi- A bill for a loi de pays (country cal stability slightly improved as, for law, ie, an act of the French Polynesia the first time in many years, no change Assembly with legal standing slightly in government took place and no lower than French national law) to attempt was made to overthrow the regulate the acquisition of landed current one through a no-confidence property by the country government motion. However, the severe eco- in the case of a landowner dying nomic crisis partly caused by years of without heirs met with strong negative instability continued, and no major reactions as soon as it was introduced changes in financial and economic in the assembly in mid-August. The policy to improve the situation appear bill’s opponents—led by heir to the to be in sight. On the other hand, Tahitian royal family Teriihinoiatua there were significant advances in the Joinville Pomare, land rights activist international plea for the country’s Monil Tetuanui, and assembly mem- decolonization by the current govern- bers Sandra Manutahi Lévy-Agami ment under President Oscar Temaru. -

ADMINISTRATIVE JUSTICE in EUROPE INTRODUCTION (History

ADMINISTRATIVE JUSTICE IN EUROPE - Report for France - INTRODUCTION (History, purpose of the review and classification of administrative acts, definition of an administrative authority) 1. Main dates in the evolution of the review of administrative acts If the principle of separation of the administrative and judicial authorities originates in the edict of Saint-Germain-en-Laye of February 1641, it was established, in its modern accepted meaning, by the revolutionary law of August 16 and 24, 1790. The creation, in Year VIII (1799), of the councils of prefecture and the Council of State, heir of the king’s council, completed the birth of French administrative justice. Thanks to the recognized special nature of the rules applicable to the administration by the Court dispute tribunal’s Blanco ruling of February 8, 1873, and according to the law of May 24, 1872, that enabled the Council of State to become a full-fledged adjudicator making its own decisions, according to the system called “delegated justice,” whereas until that time the final decision lay with the executive power, administrative law will develop, and consequently the administration’s control will assert itself. Since the early 19th century, the powers of the Council of State, of the administrative courts of appeal, created in 1987, and of the administrative courts, which in 1953 succeeded the councils of prefecture as common law judges in the administrative disputes of first resort, never ceased to assert themselves at the initiative of the legislator or the adjudicator him/herself, so as to exert ever broader and more efficient control of the administration’s acts and actions. -

Criminal Proceedings and Defence Rights in France

CRIMINAL PROCEEDINGS AND DEFENCE RIGHTS IN FRANCE This leaflet covers: Information about FTI Definitions of key legal terms Criminal proceedings and defence rights in France Useful links This booklet was last updated in February 2013 About Fair Trials International Since 1992 Fair Trial International has worked for the better protection of fair trial rights and defended the rights of people facing criminal charges in a country other than their own. Our vision is a world where every person’s right to a fair trial is respected, whatever their nationality, wherever they are accused. Fair Trials International was established to help people arrested outside their own country to defend their right to a fair trial. Every year we help hundreds of people and their families to navigate a foreign legal system by offering practical advice, including contacts of local lawyers; guidance on key issues encountered by people arrested abroad; and basic information on different legal systems and local sources of support. As a charity, we do not charge for any of the assistance that we provide. We believe that respect for fundamental rights and the rule of law are the hallmarks of a just society and that the right to a fair trial is at the heart of this. Sadly too many shocking cases of injustice demonstrate how, time and again, this most basic human right is being abused. We fight against injustice by lobbying for the legal reforms needed to ensure that the right to a fair trial is respected in practice. Working with our clients and international networks, we also campaign for changes to criminal justice laws which are being abused and overused. -

1997 Human Rights Report: France Page 1 of 12

1997 Human Rights Report: France Page 1 of 12 The State Department web site below is a permanent electro information released prior to January 20, 2001. Please see w material released since President George W. Bush took offic This site is not updated so external links may no longer func us with any questions about finding information. NOTE: External links to other Internet sites should not be co endorsement of the views contained therein. U.S. Department of State France Report on Human Rights Practices for 1997 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, January 30, 1998. FRANCE France is a constitutional democracy with a directly elected president and National Assembly and an independent judiciary. The law enforcement and internal security apparatus consists of the Gendarmerie, the national police, and municipal police forces in major cities, all of which are under effective civilian control. The highly developed, diversified, and primarily market-based economy provides residents with a high standard of living. The Government respected the human rights of its citizens, and the law and judiciary provide a means of dealing with individual instances of abuse. Long delays in bringing cases to trial and lengthy pretrial detention are problems. Racially motivated attacks by extremists declined sharply from 480 in 1995 to 195 in 1996. The Government has taken important steps to deal with violence against women and children. Women continue to face wage discrimination. Although no killings occurred in Corsica during the year, there were over 200 bombings, many of which were politically motivated RESPECT FOR HUMAN RIGHTS Section 1 Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom From: http://www.state.gov/www/global/human_rights/1997_hrp_report/france.html 1/13/03 1997 Human Rights Report: France Page 2 of 12 a. -

TAHITI NUI Tu-Nui-Ae-I-Te-Atua

TAHITI NUI Tu-nui-ae-i-te-atua. Pomare I (1802). ii TAHITI NUI Change and Survival in French Polynesia 1767–1945 COLIN NEWBURY THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF HAWAII HONOLULU Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 In- ternational (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require per- mission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824880323 (PDF) 9780824880330 (EPUB) This version created: 17 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. Copyright © 1980 by The University Press of Hawaii All rights reserved. For Father Patrick O’Reilly, Bibliographer of the Pacific CONTENTS Dedication vi Illustrations ix Tables x Preface xi Chapter 1 THE MARKET AT MATAVAI BAY 1 The Terms of Trade 3 Territorial Politics 14 Chapter 2 THE EVANGELICAL IMPACT 31 Revelation and Revolution 33 New Institutions 44 Churches and Chiefs 56 Chapter 3 THE MARKET EXPANDED 68 The Middlemen 72 The Catholic Challenge 87 Chapter 4 OCCUPATION AND RESISTANCE 94 Governor Bruat’s War 105 Governor Lavaud’s -

France 2020 Human Rights Report

FRANCE 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY France is a multiparty constitutional democracy. Voters directly elect the president of the republic to a five-year term. President Emmanuel Macron was elected in 2017. An electoral college elects members of the bicameral parliament’s upper house (Senate), and voters directly elect members of the lower house (National Assembly). Observers considered the 2017 presidential and separate National Assembly elections to have been free and fair. Under the direction of the Ministry of the Interior, a civilian national police force and gendarmerie units maintain internal security. In conjunction with specific gendarmerie units used for military operations, the army is responsible for external security under the Ministry of Defense. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security forces. Members of the security forces committed some abuses. Significant human rights issues included: violence against journalists; criminal defamation laws; and societal acts of violence and threats of violence against Jews, migrants and members of ethnic minorities, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex persons. The government took steps to investigate, prosecute, and punish officials who committed human rights abuses. Impunity was not widespread. Note: The country includes 11 overseas administrative divisions covered in this report. Five overseas territories, in French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Mayotte, and La Reunion, have the same political status as the 13 regions and 96 departments on the mainland. Five divisions are overseas “collectivities”: French Polynesia, Saint-Barthelemy, Saint-Martin, Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, and Wallis and Futuna. New Caledonia is a special overseas collectivity with a unique, semiautonomous status between that of an independent country and an overseas department. -

France's Constitution of 1958 with Amendments Through 2008

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:28 constituteproject.org France's Constitution of 1958 with Amendments through 2008 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:28 Table of contents Preamble . 3 Title I: ON SOVEREIGNTY . 3 Title II: THE PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC . 4 Title III: THE GOVERNMENT . 8 Title IV: PARLIAMENT . 9 Title V: ON RELATIONS BETWEEN PARLIAMENT AND THE GOVERNMENT . 11 Title VI: ON TREATIES AND INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS . 17 Title VII: THE CONSTITUTIONAL COUNCIL . 19 Title VIII: ON JUDICIAL AUTHORITY . 20 Title IX: THE HIGH COURT . 22 Title X: ON THE CRIMINAL LIABILITY OF THE GOVERNMENT . 22 Title XI: THE ECONOMIC, SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL COUNCIL . 23 Title XI-A: THE DEFENDER OF RIGHTS . 24 Title XII: ON TERRITORIAL COMMUNITIES . 24 Title XIII: TRANSITIONAL PROVISIONS PERTAINING TO NEW CALEDONIA . 28 Title XIV: ON THE FRENCH-SPEAKING WORLD AND ON ASSOCIATION AGREEMENTS . 29 Title XV: ON THE EUROPEAN UNION . 29 Title XVI: ON AMENDMENTS TO THE CONSTITUTION . 31 Title XVII . 31 DECLARATION OF HUMAN AND CIVIC RIGHTS OF 26 AUGUST 1789 . 31 PREAMBLE TO THE CONSTITUTION OF 27 OCTOBER 1946 . 34 CHARTER FOR THE ENVIRONMENT . 35 France 1958 (rev. 2008) Page 2 constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:28 Preamble The French people solemnly proclaim their attachment to the Rights of Man and the principles of national sovereignty as defined by the Declaration of 1789, confirmed and complemented by the Preamble to the Constitution of 1946, and to the rights and duties as defined in the Charter for the Environment of 2004. -

Penal Code Penal Code

PENAL CODE PENAL CODE With the participation of John Rason SPENCER QC Professor of Law, University of Cambridge Fellow of Selwyn College FIRST PART ENACTED PARTS Articles 111-1 to 727-2 BOOK I GENERAL PROVISIONS Articles 111-1 to 133-1 TITLE I THE CRIMINAL LAW Articles 111-1 to 113-1 CHAPTER I GENERAL PRINCIPLES Articles 111-1 to 111-5 ARTICLE 111-1 Criminal offences are categorised as according to their seriousness as felonies, misdemeanours or petty offences. ARTICLE 111-2 Statute defines felonies and misdemeanours and determines the penalties applicable to their perpetrators. Regulations define petty offences and determine the penalties applicable to those who commit them, within the limits and according to the distinctions established by law. ARTICLE 111-3 No one may be punished for a felony or for a misdemeanour whose ingredients are not defined by statute, nor for a petty offence whose ingredients are not defined by a regulation. No one may be punished by a penalty which is not provided for by the statute, if the offence is a felony or a misdemeanour, or by a regulation, if the offence is a petty offence. ARTICLE 111-4 Criminal legislation is to be construed strictly. ARTICLE 111-5 Criminal courts have jurisdiction to interpret administrative decisions of a regulatory or individual nature, and to appreciate their legality where the solution to the criminal case they are handling depends upon such examination. CHAPTER II OF THE OPERATIVE PERIOD OF A CRIMINAL LAW Articles 112-1 to 112-4 ARTICLE 112-1 Conduct is punishable only where it constituted a criminal offence at the time when it took place. -

The Ambassadors of Air Tahiti Nui Regarder Le Nombril», Explique- Jansé Wesson: Socially Aware T-Il

sommaire © MATAREVAPHOTO.COM Editorial Nos îles évoquent sans conteste le soleil, la joie de vivre et les paysages exceptionnels. Les charmes d’un paradis terrestre abondamment Tahiti & ses îles décrit par de nombreux navigateurs, écrivains, artistes. Ces charmes, nos visiteurs les retrouvent lors de leur séjour. Mais pour autant Tahiti 06 Carte de la Polynésie française n’est pas sans réserver des surprises. Nous en évoquons certaines dans ce nouveau numéro de RevaTahiti. 10 PORTFOLIO > Croisières reines Pour une découverte de manière originale de la Polynésie, nous vous 28 rendez-vous > Heiva I Tahiti invitons ainsi à embarquer pour des croisières de rêve, une autre 46 decouverte > Le vrai visage du capitaine Bligh façon d’aborder, au sens premier comme au sens figuré, nos îles. Toute leur beauté se dévoile lors de ces navigations. 54 rendez-vous Teahupo’o, histoire d’une légende > Surprise encore concernant les racines du Heiva I Tahiti, le plus 70 rendez-vous > Hokule’a en mission... important événement culturel de l’année et sans doute un des plus 78 rendez-vous > Baleines... ancien du monde car né à la fin du 19e siècle. Ces fêtes du Tiurai, 92 decouverte > Eo Himene, voix des Marquises devenus festivités du Heiva I Tahiti, sont, aujourd’hui, un temps fort de l’affirmation de l’identité polynésienne et, également, une grande 98 AGENDA célébration des traditions. 99 Les Bonnes ADRESSES Etonnement, sans doute, aussi à la vision des baleines qui sillonnent notre océan et nos côtes de juillet à septembre. En provenance des Monde mers glacées de l’Antarctique, leur milieu habituel, elles effectuent leur migration saisonnière en Polynésie. -

|||GET||| Tahiti 1St Edition

TAHITI 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Ben R Finney | 9781351487153 | | | | | Noa Noa Voyage Tahiti, First Edition About this Item: Assouline, The arms are connected by a circular crown of Tahitian gardenia enameled in green and white. Seller Inventory FT Religion in Oceania. When he returned to Paris inhe was anxious to exhibit the works he produced during his two year sojourn. The major settlement, Vaitapeis on the western side of the main islandopposite the main channel into the lagoon. Culture of indigenous Oceania. Seller Rating:. Dust Jacket Condition: Good. Price clipped, wth dollar sign still Tahiti 1st edition else a fine, clean, unmarked copy in a Brodart jacket cover. Commemorative medal for voluntary service in Free France Italian Campaign medal Medal for deportation and internment for acts of resistance Political Tahiti 1st edition and internment medal Commemorative medal of the — War Medal of a liberated France Recusant's insignia. James, NY, U. United Kingdom. The Order of Tahiti Nui was established on 5 June by the Assembly of French Polynesia to reward distinguished merit and achievements in the service to French Polynesia. Bound in publisher's "straw" cloth, lettered in brown. He also presents candidates and nominees Tahiti 1st edition promotion. Condition: Good. Condition: Stain at heal hinge, previous owner's name on front end paper. Condition: Near Fine. The insignia is a cross of four arms glazed in red enamel, terminating in a ball at each point. About this Item: N. In ancient times the island was called "Pora pora mai te pora", meaning "created by the gods" in the local Tahitian dialect.