A Change Is Gonna Come

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

50Th Anniversary Celebration: 1960S Music & Musical Artists Display

Clemson University TigerPrints Presentations University Libraries 12-2016 50th Anniversary Celebration: 1960s Music & Musical Artists Display Maggie Mason Smith Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/lib_pres Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Mason Smith, Maggie, "50th Anniversary Celebration: 1960s Music & Musical Artists Display" (2016). Presentations. 99. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/lib_pres/99 This Display is brought to you for free and open access by the University Libraries at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Presentations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1960s Music & Musical Artists Display December 2016 1960s Music & Musical Artists Display Photograph taken by Micki Reid, Cooper Library Public Information Coordinator Display Description The final 50th Anniversary book display features 1960s music and musical artists. Genres featured include British Invasion; Motown/R&B; Surf, Psychedelic, Roots, Hard, and Folk Rock and protest music. Formats include print, DVD, and CD. Come to Cooper to read about, watch, or listen to The Beatles, Aretha Franklin, The Beach Boys, Janis Joplin, and Bob Dylan (among many others!) before the holidays. The display will be up throughout December and items on display can be checked out at the Library Services Desk. - Posted on Clemson University Libraries’ Blog, December 2nd 2016 Music on Display • Armstrong, Louis. The Definitive Collection. Hip-O/Verve, 2006. CD. M1630.18.A76D34 2006. • The Beatles. Abbey Road. Parlophone, 1987. CD. M1741.18.B34A23 1987. • ---. The Beatles. Parlophone, 1987. CD. M1741.18.B34B33 1987. • ---. The Beatles 1962-1966. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Sam Cooke.Pptx

Sam Cooke Group 5: Michael Muradian, Vinh Dang, Yazan Alkhatib http://assets.rollingstone.com/assets/images/artists/304x304/sam-cooke.jpg Sam Cooke Overview • Commonly referred as the "King of Soul" • Famous black gospel, soul, R&B, and pop singer and songwriter o Considered a pioneer/founder of soul music • Created 29, top 40 hits during his musical career (1957-1964) o most famous songs include: "You Send Me," "Chain Gang," and "A Change is Gonna Come" • Among first black performers to develop business side of musical career o founded a record label, and publishing company Sam Cooke Overview • Active in African-American Civil Rights Movement • Cooke's life was abruptly ended at the young age of 33 (December 11, 1964) o Cooke was fatally shot while drunk by a hotel manager in Los Angeles o Controversial • Inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1986 Early Life • Born on January 22nd, 1931 in Clarksdale, Mississippi • One of eight children born to Charles Cook Sr., and Annie May Cook o Father was a traveling minister of Baptist faith • Born with the name Samuel Cook, but later developed stage name of Sam Cooke • Attended Wendell Phillips Academy High School in Chicago Development of Musical Career • Began career at nine years old in the group, "The Singing Children" o sang with siblings • Sang for the "Highway QC's" at age 15 • Became lead singer in "The Soul Stirrers" o introduced revolutionary two- lead singing o gospel group attracted younger crowds due to good looks o signed with Specialty Records o songs include "Jesus Gave Me Water," "Peace in the Valley," "Jesus Paid the Debt" Sam Cooke's Musical Style • Considered to have been unique. -

The Racialization of Jimi Hendrix Marcus K

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Senior Honors Theses Honors College 2007 The Racialization of Jimi Hendrix Marcus K. Adams Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/honors Part of the African American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Adams, Marcus K., "The Racialization of Jimi Hendrix" (2007). Senior Honors Theses. 23. http://commons.emich.edu/honors/23 This Open Access Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact lib- [email protected]. The Racialization of Jimi Hendrix Abstract The period of history immediately following World War Two was a time of intense social change. The nde of colonialism, the internal struggles of newly emerging independent nations in Africa, social and political changes across Europe, armed conflict in Southeast Asia, and the civil rights movement in America were just a few. Although many of the above conflicts have been in the making for quite some time, they seemed to unite to form a socio-political cultural revolution known as the 60s, the effects of which continues to this day. The 1960s asw a particularly intense time for race relations in the United States. Long before it officially became a republic, in matters of race, white America collectively had trouble reconciling what it practiced versus what it preached. Nowhere is this racial contradiction more apparent than in the case of Jimi Hendrix. Jimi Hendrix is emblematic of the racial ideal and the racial contradictions of the 1960s. -

A Change Is Gonna Come

A CHANGE IS GONNA COME: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE BENEFITS OF MUSICAL ACTIVISM IN THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT By ERIN NICOLE NEAL A Capstone submitted to the Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Liberal Studies Written under the direction of Dr. Stuart Z. Charmé And approved by ____________________________________ Dr. Stuart Z. Charmé Camden, New Jersey January 2021 CAPSTONE ABSTRACT A Change Is Gonna Come: A Critical Analysis Of The Benefits Of Musical Activism In The Civil Rights Movement by ERIN NICOLE NEAL Capstone Director: Dr. Stuart Z. Charmé The goal of this Capstone project is to understand what made protest music useful for political activists of the Civil Rights Movement. I will answer this question by analyzing music’s effect on activists through an examination of the songs associated with the movement, regarding lyrical content as well as its musical components. By examining the lyrical content, I will be evaluating how the lyrics of protest songs were useful for the activists, as well as address criticisms of the concrete impact of song lyrics of popular songs. Furthermore, examining musical components such as genre will assist in determining if familiarity in regards to the genre were significant. Ultimately, I found that music was psychologically valuable to political activists because music became an outlet for emotions they held within, instilled within listeners new emotions, became a beacon for psychological restoration and encouragement, and motivated listeners to carry out their activism. Furthermore, from a political perspective, the lyrics brought attention to the current socio-political problems and challenged social standards, furthered activists’ political agendas, persuaded the audience to take action, and emphasized blame on political figures by demonstrating that socio-political problems citizens grappled with were due to governmental actions as well as their inactions. -

90'S Medley Rihanna Medley Motown Medley Prince

Adele - Rolling in the Deep Jackson 5 - ABC Outkast - Miss Jackson 90’S MEDLEY Alabama Shakes - Hold on James Brown - Get Up Oa That Thing Outkast - Rosa Parks TLC Alicia Keys - Empire State of Mind James and Bobby Purify - Shake A Tail Feather Patrice Ruschen - Forget Me Nots Usher Alicia Keys - If I Ain’t Got You James Blake - Limit To Your Love Percy Sledge - You Really Got a Hold On Me Montell Jordan Al Green - Let’s Stay Together Jamie XX - Good Times Pharrell – Happy Mark Morrison Al Green - Take Me to the River Janelle Monae - Tightrope Prince – I Wanna Be Your Lover Next Amy Whinehouse - Valerie Jerry Lee Lewis - Great Balls of Fire Prince - Kiss Beck – Where It’s At Justin Timberlake - Can’t Stop The Feeling Ray Charles - Georgia Beyonce – Crazy In Love Justin Timberlake - Rock Your Body R Kelly - Remix to Ignition RIHANNA MEDLEY Beyonce - Love on Top King Harvest - Dancing in the Moonlight Sade - By Your Side What’s My Name Beyonce - Party Kendrick Lamar – If These Walls Could Talk Sade - Smooth Operator We Found Love Bill Withers - Ain’t No Sunshine Leon Bridges - Coming Home Sade - Sweetest Taboo Work Blondie – Rapture Lil Nas X - Old Town Road Sam Cooke - Wonderful World Blood Orange - You’re Not Good Enough Sam Cooke - Cupid Lionel Richie - All Night Long MOTOWN MEDLEY Bob Carlisle/Je Carson - Butterfly Kisses Little Richard - Good Golly Miss Molly Sam Cooke - Twistin’ Your Love Keeps Lifting Me Higher and Higher Bruno Mars - 24k Magic Lizzo - Juice Sam Cooke – You Send Me You Really Got a Hold On Me Bruno Mars - Treasure -

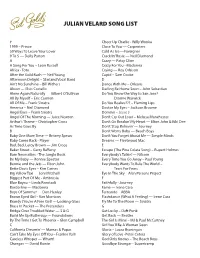

Julian Velard Song List

JULIAN VELARD SONG LIST # Cheer Up Charlie - Willy Wonka 1999 – Prince Close To You — Carpenters 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover Cold As Ice —Foreigner 9 To 5 — Dolly Parton Cracklin’ Rosie — Neil Diamond A Crazy — Patsy Cline A Song For You – Leon Russell Crazy For You - Madonna Africa - Toto Crying — Roy Orbison After the Gold Rush — Neil Young Cupid – Sam Cooke Afternoon Delight – Starland Vocal Band D Ain’t No Sunshine – Bill Withers Dance With Me – Orleans Alison — Elvis Costello Darling Be Home Soon – John Sebastian Alone Again Naturally — Gilbert O’Sullivan Do You Know the Way to San Jose? — All By Myself – Eric Carmen Dionne Warwick All Of Me – Frank Sinatra Do You Realize??? – Flaming Lips America – Neil Diamond Doctor My Eyes – Jackson Browne Angel Eyes – Frank Sinatra Domino – Jesse J Angel Of The Morning — Juice Newton Don’t Cry Out Loud – Melissa Manchester Arthur’s Theme – Christopher Cross Don’t Go Breakin’ My Heart — Elton John & Kiki Dee As Time Goes By Don’t Stop Believin’ — Journey B Don’t Worry Baby — Beach Boys Baby One More Time — Britney Spears Don’t You Forget About Me — Simple Minds Baby Come Back - Player Dreams — Fleetwood Mac Bad, Bad, Leroy Brown — Jim Croce E Baker Street – Gerry Raerty Escape (The Pina Colata Song) – Rupert Holmes Bare Necessities - The Jungle Book Everybody’s Talkin’ — Nilsson Be My Baby — Ronnie Spector Every Time You Go Away – Paul Young Bennie and the Jets — Elton John Everybody Wants To Rule The World – Bette Davis Eyes – Kim Carnes Tears For Fears Big Yellow Taxi — Joni Mitchell Eye In -

Sam Cooke, “A Change Is Gonna Come”

Sam Cooke, “A Change is Gonna Come” Sam Cooke was one of the pioneers of Soul music, topping the charts with hits such as “Wonderful World” and “Chain Gang.” While he began as a Gospel singer, Cooke’s hits were generally upbeat and rarely if ever crossed into political territory. But by the early 1960s, as the civil rights movement was growing stronger, Cooke became aware of the political power of music. In October, 1963, despite his star status, he and members of his band were arrested when they tried to get a room at a whites- only motel in Shreveport, Louisiana. Cooke recorded “A Change is Gonna Come” that December. It was not a major commercial hit, but it quickly became one of the most influential songs of the civil rights movement. Numerous artists, including Tina Turner, Lil Wayne and Seal, have covered the song. On the night he won the 2008 election, Barack Obama told cheering crowds, "It's been a long time coming, but tonight, change has come to America." Excerpt from Lyrics I go to the movie And I go down town somebody keep telling me don't hang around Its been along time coming But I know a change is gonna come, oh yes it will Questions for Discussion 1. Cooke was known as one of the most talented vocalists in the history of popular music. How does he use his voice to convey emotion in this song? 2. Do the lyrics refer specifically to the civil rights movement? What story do they tell? 3. -

Repertoire Patricia Foort

Repertoire Patricia Foort Soul/Motown: 1 Ain't got no (Nina Simone) 2 A song for you (Donny Hathaway) 3 Ain't no stopping us now(Luther Vandross) 4 Ain't no sunshine (Bill Withers of Jacksons) 5 Ain't nobody (Chaka Khan) 6 All in love is fair(Stevie Wonder) 7 All my life (K-ci and Jojo 8 All night long (Lionel Ritchie) 9 All of me (John Legend) 10 All the love in the world (Dionne Warwick) 11 Allways There (Incognito) 12 Almaz (Randy Crawford) 13 And I love you so (Perry Como) 14 Ave Maria(Beyonce) 15 Baby can I hold you tonight (Tracey Chapman) 16 Baby come to me (Patty Austin) 17 Baby I love you(Aretha Franklin) 18 Blueberry Hill (Fats Domino) 19 Bring it on home (Sam Cooke) 20 Chain of fool(Aretha Franklin) 21 Change is gonna come(Sam Cooke) 22 Clown (Emili Sande) 23 Dirty old man (The Three Degrees) 24 Do that to me (Captain and Tenille) 25 Don't let the sun go down (Oleta Adams) 26 Don't you worry 'bout a thing(Incognito) 27 Do you know where you're going to (Diana Ross) 28 Dr Feelgood (Aretha Franklin) 29 End of the road (Boys II Men) 30 Endlessly (Randy Crawford) 31 Fire (Pointer Sisters) 32 For all we know (Donny Hathaway) 33 For once in my life (Stevie Wonder/Trijntje) 34 Get here (Oleta Adams) 35 Go Like Elijah(Chi Coltrane) 36 Good Times (Chiq) 37 Hallelujah(Lisa Lois) 38 Happy (Pharrell Williams) 39 Happy Birthday (Stevie Wonder) 40 Hello (L. -

REVOLUTIONARY VOICES Take This Short Quiz to Test Your Knowledge

TODAY’S MUSIC EDUCATION RESOURCE Name: STUDENT QUIZ REVOLUTIONARY VOICES Take this short quiz to test your knowledge. Q1: Why is the human voice a more powerful instrument than other instruments? Q2: What did the Hutchinson Family Singers sing about? Q3: What is the name of the song sung by Vera Lynn about peace after the war? Q4: Who is considered “The King of Soul” and sung “A Change is Gonna Come” during the turn of liberalism in America? Q5: Who co-wrote “Freedom,” and released it on her 2016 album Lemonade? Q6: What is the song “Freedom” about? Q7: What is another one of Beyoncé’s “anthem” songs about women’s empowerment? Q8: In what ways has John Legend contributed to social movements? Q9: What popular artist evokes a feeling of acceptance and kindness from audiences at his concerts? Q10: Can you name any other songs/artists that might fall under this category of “revolu- tionary voices”? © 2019 IN TUNE PARTNERS, LLC TODAY’S MUSIC EDUCATION RESOURCE Name: STUDENT QUIZ MEDLEY’S MASH-UPS & MORE Take this quick quiz to test your knowledge. Q1: Which type of arrangement includes two or more songs that play simultaneously? Q2: Which type of arrangement plays two or more songs one after another? Q3: How many chords are in the most common chord progression in popular music? Q4: What is the name of the band who created a medley including 50 songs from the early 2000s? Q5: What does Postmodern Jukebox do as a group? Q6: What elements are commonly used in the “musical recipe” for a modern pop arrange- ment? Q7: What elements did Pentatonix have to synchronize to create their medley? Q8: Can you give an example of a theme you could write a medley about? What songs would be included in it? Q9: Why are chord progressions important to pay attention to when creating a mash-up? Q10: What song did Andy Wu mash together with “Apologize” by One Republic? © 2019 IN TUNE PARTNERS, LLC TODAY’S MUSIC EDUCATION RESOURCE Name: STUDENT QUIZ LAUREN DAIGLE Take this short quiz to test your knowledge. -

View Song List

Piano Bar Song List 1 100 Years - Five For Fighting 2 1999 - Prince 3 3am - Matchbox 20 4 500 Miles - The Proclaimers 5 59th Street Bridge Song (Feelin' Groovy) - Simon & Garfunkel 6 867-5309 (Jenny) - Tommy Tutone 7 A Groovy Kind Of Love - Phil Collins 8 A Whiter Shade Of Pale - Procol Harum 9 Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) - Nine Days 10 Africa - Toto 11 Afterglow - Genesis 12 Against All Odds - Phil Collins 13 Ain't That A Shame - Fats Domino 14 Ain't Too Proud To Beg - The Temptations 15 All About That Bass - Meghan Trainor 16 All Apologies - Nirvana 17 All For You - Sister Hazel 18 All I Need Is A Miracle - Mike & The Mechanics 19 All I Want - Toad The Wet Sprocket 20 All Of Me - John Legend 21 All Shook Up - Elvis Presley 22 All Star - Smash Mouth 23 All Summer Long - Kid Rock 24 All The Small Things - Blink 182 25 Allentown - Billy Joel 26 Already Gone - Eagles 27 Always Something There To Remind Me - Naked Eyes 28 America - Neil Diamond 29 American Pie - Don McLean 30 Amie - Pure Prairie League 31 Angel Eyes - Jeff Healey Band 32 Another Brick In The Wall - Pink Floyd 33 Another Day In Paradise - Phil Collins 34 Another Saturday Night - Sam Cooke 35 Ants Marching - Dave Matthews Band 36 Any Way You Want It - Journey 37 Are You Gonna Be My Girl? - Jet 38 At Last - Etta James 39 At The Hop - Danny & The Juniors 40 At This Moment - Billy Vera & The Beaters 41 Authority Song - John Mellencamp 42 Baba O'Riley - The Who 43 Back In The High Life - Steve Winwood 44 Back In The U.S.S.R. -

By Song Title

Solar Entertainments Karaoke Song Listing By Song Title 3 Britney Spears 2000s 17 MK 2010s 22 Lily Allen 2000s 39 Queen 1970s 679 Fetty Wap 2010s 711 Beyonce 2010s 1973 James Blunt 2000s 1999 Prince 1980s 2002 Anne Marie 2010s #ThatPower Will.I.Am & Justin Bieber 2010s 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & The Aces 1960s 1 800 273 8255 Logic & Alessia Cara & Khalid 2010s 1 Thing Amerie 2000s 10/10 Paolo Nutini 2010s 10000 Hours Dan & Shay & Justin Bieber 2010s 18 & Life Skid Row 1980s 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 1990s 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue 2000s 20th Century Boy T Rex 1970s 21 Guns Green Day 2000s 21st Century Breakdown Green Day 2000s 21st Century Christmas Cliff Richard 2000s 22 (Twenty Two) Taylor Swift 2010s 24K Magic Bruno Mars 2010s 2U David Guetta & Justin Bieber 2010s 3 AM Busted 2000s 3 Nights Dominic Fike 2010s 3 Words Cheryl Cole 2000s 30 Days Saturdays 2010s 34+35 Ariana Grande 2020s 4 44 Jay Z 2010s 4 In The Morning Gwen Stefani 2000s 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake 2000s 5 Colours In Her Hair McFly 2000s 5,6,7,8 Steps 1990s 500 Miles (I'm Gonna Be) Proclaimers 1980s 7 Rings Ariana Grande 2010s 7 Things Miley Cyrus 2000s 7 Years Lukas Graham 2010s 74 75 Connells 1990s 9 To 5 Dolly Parton 1980s 90 Days Pink & Wrabel 2010s 99 Red Balloons Nena 1980s A Bad Dream Keane 2000s A Blossom Fell Nat King Cole 1950s A Change Would Do You Good Sheryl Crow 1990s A Cover Is Not The Book Mary Poppins Returns Soundtrack 2010s A Design For Life Manic Street Preachers 1990s A Different Beat Boyzone 1990s A Different Corner George Michael 1980s