Rhodesia - the Propaganda War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sr. Janice Mclaughlin Office: (202) 546-7961 Home: (202) 265-3266

THE AFRICA FUNDm 305 E. 46th St. NewYork, N.Y. 10017m(212)838-5030 HOLD FOR RELEASE IN THE AM MONDAY, MARCH 6, 1978 Contact: Sr. Janice McLaughlin Office: (202) 546-7961 Home: (202) 265-3266 RHODESIA TO BEGIN TRIAL OF CATHOLIC COMMISSION MEMBERS New York, N.Y. March 6, 1978 ----A Catholic Church report documenting the use Of torture, repressioh and propaganda by the white Minority regime of Ian Smith in Rhodesia is being published in the U. S. Its American release coincides with the trial scheduled for March r of three members of the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace in Rhodesia, who are charged with subversion for the pre paration and publication of this report. A fourth member of the Commission, Sister Janice McLaughlin of Pittsburgh, Pa., was arrested for three weeks and deported September 21, 1977 for her role in assembling the controversial document. "Rhodesia: The Propaganda War" helps to illustrate why Smith's internal settlement, which leaves the oppressive army and military forces intact, will not be acceptable to the majority of the population who have suffered at the hands of these forces. The orginal papers comprising the report were circulated within Rhodesia in mimeographed form during July and August, 1977. On August 31 a team of eight police officers searched the Commistion's office, confiscated the files, detained Sr. Janice at Chikurubi prison outside Salisbury and charged three other members with publishing material "likely to cause fear, alarm or despondency," and of violating the Official Secrets Act. The Catholic Institute for International (more) Page 2 Relations in London compiled the papers and published them in booklet form on September 21 after long deliberation between lawyers and church officials whether the publication would further endanger the four Commission members charged with its preparation. -

Religious Jubilarians 21

October 6, 2011 CATHOLIC NEW YORK • Religious Jubilarians 21 Celebrating Our RELIGIOUS JUBILARIANS A CATHOLIC NEW YORK SPECIAL SECTION TEACHER AND STUDENT—Sister Janice McLaughlin, M.M., president of the Maryknoll Sisters, oversees the prog- ress of a seminarian at St. Paul’s Seminary in Juba, South Sudan, who was one of her students in a peace-building workshop over the summer following the independence of the new nation. Sister Janet, who has served as a mission- er in several African countries, made the trip in celebration of her golden jubilee of religious life. Courtesy of Maryknoll Maryknoll Sister’s Jubilee Gift Was Sharing Tools of Peace in South Sudan knoll Sisters, are supporting the venture with per- southern Africa. By JOHN WOODS sonnel and funds. A total of 24 sisters, brothers and Her students were seminarians of St. Paul’s Sem- priests from 14 congregations have begun working inary in Juba; nursing students, including religious aryknoll Sister Janice McLaughlin cel- in the new country. sisters, at a Catholic health training institute; and ebrated her golden jubilee by returning When Sister Janice arrived in South Sudan on employees of Radio Bakhita, a Catholic station. Mto Africa this summer to help the people July 25, the nation had become independent little Lessons utilized various methods of instruction of the continent’s newest nation, the Republic of more than two weeks before. She found a land with including role-playing exercises, journaling, case South Sudan, learn valuable lessons about how to very few paved roads or buildings. Poverty is a fact studies, films and music. -

THE MESSIANIC FEEDING of the MASSES an Analysis of John 6 in the Context of Messianic Leadership in Post-Colonial Zimbabwe

8 BiAS - Bible in Africa Studies THE MESSIANIC FEEDING OF THE MASSES An Analysis of John 6 in the Context of Messianic Leadership in Post-Colonial Zimbabwe Francis Machingura UNIVERSITY OF BAMBERG PRESS Bible in Africa Studies Études sur la Bible en Afrique Bibel-in-Afrika-Studien 8 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung des Deutschen Akademischen Austauschdienstes (DAAD) Bible in Africa Studies Études sur la Bible en Afrique Bibel-in-Afrika-Studien edited by Joachim Kügler, Lovemore Togarasei, Masiiwa R. Gunda, Eric Souga Onomo in cooperation with Ezra Chitando and Nisbert Taringa Volume 8 University of Bamberg Press 2012 The Messianic Feeding of the Masses An Analysis of John 6 in the Context of Messianic Leadership in Post-Colonial Zimbabwe by Francis Machingura University of Bamberg Press 2012 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Informationen sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de/ abrufbar Diese Arbeit wurde von der Fakultät Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaft der Universität Bayreuth als Doktorarbeit unter dem Titel “Messiahship and Feeding of the Masses: An Analysis of John 6 in the Con- text of Messianic Leadership in Post-Colonial Zimbabwe” angenommen. 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Joachim Kügler 2. Gutachter: PD Dr. habil. Ursula Rapp Tag der mündlichen Promotionsprüfung: 06.02.2012 Dieses Werk ist als freie Onlineversion über den Hochschulschriften-Server (OPUS; http://www.opus-bayern.de/uni-bamberg/) der Universitätsbiblio- thek Bamberg erreichbar. Kopien und Ausdrucke dürfen nur zum privaten und sonstigen eigenen Gebrauch angefertigt werden. Herstellung und Druck: Digital Print Group, Nürnberg Umschlagfoto: © http://photos.wfp.org Umschlaggestaltung: Joachim Kügler/Dezernat Kommunikation und Alumni der Otto-Friedrich-Universität Bamberg Text-Formatierung: F. -

BZS Review June 2021

Zimbabwe Review Issue 21/2 June 2021 ISSN 1362-3168 The Journal of the Britain Zimbabwe Society BZS is 40! See page 15 for details of a special 40th anniversary meeting on 12 June 2021 What Kind of In-patient Psychiatry for In this issue ... Africa? Derek Summerfield reports 1 What Kind of In-patient Psychiatry for Africa? page 1 from Zimbabwe 2 Book Review: Blue Remembered Sky page 3 Global mental health is an expanding field. Yet 3 Names in Zimbabwe’s State capture page 4 little or no attention has been paid to evaluating 4 The Impact of COVID-19 on Student Life page 5 the culture of psychiatry prevailing in in-patient 5 Book Review: They Called You Dambudzo: a memoir by Flora Veilt-Wild page 6 services across Africa. 6 Book Review: Then a Wind Blew page 8 In Zimbabwe, in-patient psychiatry has been heavily 7 Remembering Joshua Mahlathini pathologising, with over-reliance on the diagnosis of Mpofu (1939 –2021) page 9 8 Obituary: Sister Janice McLaughlin page 10 schizophrenia and on antipsychotic polypharmacy 9 Zimbabwean gardens in the UK page 11 (using multiple medications simultaneously for one 10 News page 14 person). It is not helpful that the next generation of 11 BZS is 40! (Plans for our anniversary) page 15 African doctors are learning unmediated Western 12 Research Day 2021 (Zimbabwean Migration) page 16 psychiatry, with little credence given to background cultural factors and mentalities shaping presenta - which a person’s muscles contract uncontrollably), tions. Some of the psychiatric and social conse - which are commonly visible on the wards. -

Southern Africa, Vol. 13, No. 2

Southern Africa, Vol. 13, No. 2 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nusa198002 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Southern Africa, Vol. 13, No. 2 Alternative title Southern AfricaSouthern Africa News BulletinRhodesia News Summary Author/Creator Southern Africa Committee Publisher Southern Africa Committee Date 1980-02-00 Resource type Magazines (Periodicals) Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Zimbabwe, United States, Namibia, South Africa, Southern Africa (region) Coverage (temporal) 1980-00-00 Source Northwestern University Libraries Rights By kind permission of the Southern Africa Committee. The article entitled "Overview: Looking to the Future" is used by kind permission of Jennifer Davis. -

Interview with Ted Lockwood

Interview with Ted Lockwood "It was very easy to sort of say, well, the liberation struggle, they're the heroes. They are the good people, and I don't want to hear anything bad about them. The more I stayed with it, the more I felt sympathy for everybody else. How difficult it is, really, to have a peaceful society as well as a just society come out of this." — Ted Lockwood Introduction Lawyer, Episcopal priest, and activist Edgar (Ted) Lockwood is from a comfortably well- off and conventionally conservative New England family background. He went to law school after serving on a Navy destroyer during World War II. After only a few years as a lawyer, he went back to school to study theology in 1957, at the age of 37. From the beginning, he says, his activist theological convictions were tied to the issue of racism. His participation in the Selma-Montgomery march in 1964, as part of a delegation who flew down from Massachusetts in response to the call for support by Martin Luther King Jr., solidified the commitment. But it wasn't until the end of the 1960s that he became involved with international African issues, beginning with an Institute for Policy Studies research project on the policies of church denominations for handling their investments. Lockwood soon became one of the persistent agitators within the Episcopal Church for full economic disengagement from apartheid, working with his close friend Bill Johnston of the Episcopal Churchmen for South Africa.[1] He made his first trip to South Africa in 1971 as an observer when the South African regime placed Gonville ffrench-Beytagh, the Anglican dean of the cathedral in Johannesburg, on trial under the Terrorism Act. -

By Word and Deed, Missioners Speak to People of Love

By word and deed , missioners speak to people of love. Maryknoll Sister Janice McLaughlin helps build a new society in Zimbabwe. If you have moved or your address Is incorrect, please fill out coupon on page 58 A young woman at the Zimbabwe Rusununguko (meaning "Freedom") school to train former refugees. The butterfly Do not presume to tell me, 0 impetuous man, Where I may or may not fly; I am an untamed spirit Veering with the winds of my choosing. Your own civilization has become A narcissistic monster Whose burial ceremonies will remain unsung For lack of mourners. But I am everlasting, For the spirit that is in me Cannot be trammeled in the seines of time and space But will unceasingly mingle with the eternal breezes, Even as you look at my broken wing Or my body, mutilated by your tar-squelching monster of steel, And, in your ignorance, pronounce me dead. And therefore as I flutter-flutter Or dissect the air in geometric designs And light upon these soft petals Or the trunk of a mighty oak, My seeming frailty is my strength. For I, being all Spirit, Am the very essence of freedom And my triumph over your chains Is the triumph of freedom itself. Daniel Kunene South African poet Cover: With good cause, a Zimbabwean boy exults over a bumper harvest, for malnutrition is still the most pressing problem. Since independence, black Zimbabwean farmers have been getting more technical help to grow better crops, a goal the Church has pursued for years. Mqaaneortbc Volume 76, Number 2 Catholic Forci£11 J\lli!M>11 Soa<ly of MnCnCa Publilh<t l...eoJ Somro<t, M.M. -

Geraint Jones

© University of the West of England Do not reproduce or redistribute in part or whole without seeking prior permission from the Rhodesian Forces oral history project coordinators at UWE Geraint Jones Geraint's family is from South Wales, where he was born. He was brought up in Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) where his parents lived until the 1950s. They then returned to Uganda. Started University in South Africa and soon after was recruited into the BSAP in 1974. Moved into Special Branch in 1977. Volunteered for PATU at some stage. Briefly left Rhodesia at the end of his first contract in 1978, however returned shortly afterwards. Left Rhodesia for South Africa in 1980 and joined the SA Police Reserve there at the time. Came to the UK for a working holiday in 1981 and returned again in 1988 to join the RAF in 1989. Left the RAF in 1993 and returned to South Africa, where he joined the SA Police Reserve again. Moved to Spain in 2000 and finally returned to the UK in 2001. Still travels a lot with his work. This is Annie Berry interviewing Geraint Jones on Monday the 29th of June 2009 in Bristol. Thank you very much for travelling all the way to Bristol today. You’re welcome. Perhaps we could just start with you saying how you came to be in Rhodesia initially? My family’s roots, my family is from South Wales but I was brought up in Africa. My first memory in fact is in what’s now Zambia, Northern Rhodesia. My parents lived there in the late fifties and then came back to the UK for a couple of years and went back to Africa to Uganda in the early sixties. -

Ÿþm Icrosoft W

THE AFRICA FUNDm 305 E. 46th St. NewYork, N.Y. 10017m(212)838-5030 THE AFRICA FUNDm 305 E. 46th St. NewYork, N.Y. 10017m(212)838-5030 HOLD FOR RELEASE IN THE AM MONDAY, MARCH 6, 1978 Contact: Sr. Janice McLaughlin Office: (202) 546-7961 Home: (202) 265-3266 RHODESIA TO BEGIN TRIAL OF CATHOLIC COMMISSION MEMBERS New York, N.Y. March 6, 1978 ---- A Catholic Church report documenting the use Of torture, repressioh and propaganda by the white Minority regime of Ian Smith in Rhodesia is being published in the U. S. Its American release coincides with the trial scheduled for March r of three members of the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace in Rhodesia, who are charged with subversion for the preparation and publication of this report. A fourth member of the Commission, Sister Janice McLaughlin of Pittsburgh, Pa., was arrested for three weeks and deported September 21, 1977 for her role in assembling the controversial document. "Rhodesia: The Propaganda War" helps to illustrate why Smith's internal settlement, which leaves the oppressive army and military forces intact, will not be acceptable to the majority of the population who have suffered at the hands of these forces. The orginal papers comprising the report were circulated within Rhodesia in mimeographed form during July and August, 1977. On August 31 a team of eight police officers searched the Commistion's office, confiscated the files, detained Sr. Janice at Chikurubi prison outside Salisbury and charged three other members with publishing material "likely to cause fear, alarm or despondency," and of violating the Official Secrets Act. -

Free at Last? James Roberts and Janice Mclaughlin Consider Zimbabwe’S Uncertain Future

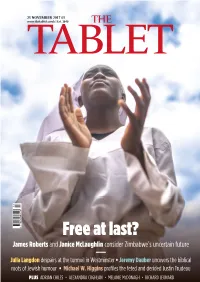

25 November 2017.qxp_Cover 11/21/17 6:59 PM Page 1 25 NOVEMBER 2017 £3 www.thetablet.co.uk | Est. 1840 THE TABLET 47 9 770039 883226 Free at last? James Roberts and Janice McLaughlin consider Zimbabwe’s uncertain future Julia Langdon despairs at the turmoil in Westminster • Jeremy Dauber uncovers the biblical roots of Jewish humour • Michael W. Higgins profiles the feted and derided J ustin Trudeau PLUS ADRIAN CHILES • ALEXANDRA COGHLAN • MELANIE McDONAGH • RICHARD LEONARD 02_Tablet25Nov17 Leaders.qxp_Tablet features spread 11/21/17 6:52 PM Page 2 THE INTERNATIONAL CATHOLIC WEEKLY THE TABLET FOUNDED IN 1840 EUROPEAN he mass exodus of refugees fleeing conflicts in immigrant anti-Muslim right-wing insurgent party, POLITICS the Middle East was the biggest challenge to Alternatives for Germany (AfD), also tells a story. It is the conscience of Europe for a generation. strongest in the East, ironically Mrs Merkel’s own MERKEL’S The one European leader who stood out for heartland. And the cultural history of eastern Tthe quality of her moral leadership in that crisis was Germany is quite different from the rest. After the end BRAVERY IS Angela Merkel, the Chancellor of the Federal Republic of the Second World War, West Germany underwent a of Germany. Now she is fighting for her political life – thorough process of denazification. Extreme German very largely as a result of her vision and courage. She nationalism and anti-Semitism were largely exorcised STILL UK’S knew she was taking a political risk. And millions of from the national soul. But not in the East. -

Newsnotes a Bi-Monthly Newsletter of Information on International Justice and Peace Issues

Maryknoll Office for Global Concerns Peace, Social Justice and Integrity of Creation Maryknoll Office for Global Concerns 200 New York Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20001 NewsNotes A bi-monthly newsletter of information on international justice and peace issues November-December 2019 Vol. 44, No. 6 The Death of Robert Mugabe................................................................3 Chile: Massive Protests Over Inequality................................................4 Bolivian Elections Spark Unrest............................................................5 Climate Change and the Oceans...........................................................6 Calls for Action at the UN General Assembly .......................................7 Hong Kong Cardinal Calls for Nonviolence...........................................8 Bishops Comment on Crisis in Haiti......................................................8 Sudan and South Sudan: History and Future.......................................9 Supreme Court to Decide Fate for Dreamers.....................................10 Go to our website to sign up for a free e-subscription to NewsNotes. Amazon Synod Concludes in Rome....................................................10 Other updates are also available at www.maryknollogc.org What is at Stake in the Amazon.........................................................11 Journey for Justice in El Paso..............................................................12 Paper subscriptions to NewsNotes are available for those who do not have regular -

Rhodesia the Propagandawar

$1.00 Rhodesia The PropagandaWar This latest report from the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace in Rhodesia highlights the extent of the propaganda war being waged by the Rhodesia Front regime. It also illustrates the contradictions of the propaganda campaign-to assuage white fears on the one hand and on the other to terrorise the black popula tion in an attempt to isolate the guerrillas. As support for the nationalist cause has increased, the propaganda has become increasingly strident. It takes several forms-displaying the mutilated corpses of guerrillas and distributing photographs of them accompanied by threats, warning the black population that if they co operate with the guerillas they will be killed. The latest element in the psychological warfare is the mass dis tribution of crude leaflets depicting guerrillas as 'mad dog terrorists', responsible for killing, rape and spread ing venereal disease. At the same time the government has issued regulations which make it an offence to publish or distribute anything which may contribute to the spreading of alarm and despondency. Whilst the regime is thus actively engaged in spreading alarm and despondency among black Rhodesians, it is going to inordinate lengths to prevent white Rhodesians from knowing the truth of their situation. International coverage of the war in Rhodesia is at best mediocre. There is a dearth of foreign correspondents inside the country so that several newspapers have to rely on the same reporter writing under different names. Foreign correspondents have to be careful not to be too critical of the Rhodesian regime. Those who are too critical either have to leave the country or are deported.