PB 14-21: Is China's Property Market Heading Toward Collapse?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China Property – Equity & Bond Weekly Wrap

China Property – Equity & Bond weekly wrap Industry Overview Equity/Fixed Income | China | Real Estate/Property 26 March 2012 Macro factors dominate again Equity research Raymond Ngai, CFA >> +852 2536 3987 Equities slumped 4.9%, bonds yields widened to 13.19% Research Analyst Merrill Lynch (Hong Kong) Chinese developers’ shares fell another -4.9% w/w last week, after a 2.3% [email protected] decline. Overall stock market sentiment was not too good in the past week, with Matthew Chow, CFA >> +852 2161 7877 some soft macro numbers coming out from the US and Europe; and actually the Research Analyst Merrill Lynch (Hong Kong) HSCEI index was also down 5% w/w last week, on concerns of weaker economic [email protected] growth (as well as speculation over possible political tensions within China.) Sunny Tam, CFA >> +852 2536 3446 Chinese developers’ bond yields also widened another 62bps to an average Research Analyst 13.19% vs 12.57% in the week before. In the past week, macro factors seem to Merrill Lynch (Hong Kong) dominate share/bond prices again. However, looking ahead March sales numbers [email protected] for developers to be released in early April may give more indication as to how Liying Du >> +852 2161 7008 Research Analyst realistic developers’ 2012 sales targets are, and could provide more company Merrill Lynch (Hong Kong) specific drivers for the sector. [email protected] Credit Research Proposal for more property tax pilot cities approved Alwyn Pang, CFA +852 2536 3485 Last week, the National Development and Reform Committee's 2012 Economic Research Analyst Reform Proposals were approved by the State Council. -

SOHO CHINA LIMITED SOHO中國有限公司 (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with Limited Liability) 13.51A (Stock Code: 410)

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited 14.58(1) take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to Note 5, 13.52 its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. SOHO CHINA LIMITED SOHO中國有限公司 (incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) 13.51A (Stock Code: 410) DISCLOSEABLE TRANSACTION PROPOSED ACQUISITION OF SHANGHAI TIANSHAN ROAD PROJECT PROPOSED ACQUISITION The Board wishes to announce that on 17 April 2012, the Company and SOHO Shanghai, a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Company, as purchaser entered into the Framework Agreement with Greentown Holdings and the Vendors, as vendors for the acquisition of the entire equity interests in Greentown Plaza Development and all the rights and title to the Loans at an aggregate consideration of RMB2,137,720,000 (subject to adjustments, if any). As at the date of this announcement, the registered capital of Greentown Plaza Development is RMB100,000,000 and is owned as to 70% by Greentown Real Estate and 30% by MaAnShan Development. Greetown Plaza Development is responsible for development of the Tianshan Road Project. The Tianshan Road Project is at the most prime location of the Hongqiao Foreign Trade Center, in Changning District, Shanghai. Being the first business district for foreign enterprises in Shanghai, this area is home to over 4,400 enterprises and organisations with a high concentration of foreign enterprises (over 50% of the companies are foreign invested enterprises including many multinational companies such as Intel, GE, Samsung and Shell). -

International China

International China and an example that firms from other parts of the world can learn from, instead of trying to become one of the top US and UK firms.” Where else in the world have Similar ambitions are evident in The Lawyer’s inter- you seen a law firm growing views with Fangda chair of management committee by 27 per cent year-on-year Jonathan Zhou and Han Kun’s CEO Joyce Li. Han Kun for 15 consecutive years? We emerged as the fastest growing firm in last year’s China Land of report after tripling its annual turnover between 2013 expect to reach the $1bn and 2015. It also more than doubled its revenue per mark in five years” lawyer (RPL) over the same period. In 2016, its revenue Anthony Qiao, Zhong Lun grew again by 40 per cent from RMB320m in 2015 to RMB450m. the bold So why are these three firms striding ahead of the rest of Chinese firms and how can they reach their ambitious goals? Here are the key findings ofThe Lawyer’s research. Three firms from the China Top 30 “We’re not trying to duplicate the models of any suc- cessful global firms, because China is vastly different Dare to change stand out for their stunning growth from the US or the UK market,” says Zhong Lun’s part- All three firms are developing at an extraordinary pace and unshakeable belief that they will ner and CEO Anthony Qiao. “We want to be a global thanks to recent strategic overhauls and some hard Yun Kriegler be challengers to the global elite Chinese firm.” decisions. -

China to Keep Watch on TPP

Table for strangers Hainan helps visitors Memory protection Special police target tourism An app connects amateur chefs industry irregularities in Sanya with willing dining companions Database to be created on > CHINA, PAGE 4 > LIFE, PAGE 9 the Nanjing Massacre > p3 MONDAY, October 12, 2015 chinadailyusa.com $1 COMMERCE China to keep watch on TPP Such trade deals can disrupt non-signatories: offi cial By ZHONG NAN highly unlikely that the TPP would in Beijing lead to the creation of a trade bloc [email protected] that excludes China. “The economic development China will conduct comprehensive mode in China has already changed and systematic assessments of the from low-end product trade to ‘going fallout from the Trans-Pacifi c Part- global’ strategies like setting up or nership, a broad agreement between moving manufacturing facilities and 12 Pacifi c Rim countries, including to more direct investment in over- Japan and the United States, since it seas markets,” said Fan. believes that such deals have disrup- Besides the US, other signatories tive eff ects on non-signatory nations, to the TPP are Australia, Brunei, a top government offi cial said. Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mex- Commerce Minister Gao Hucheng ico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore said China is of the view that changes and Vietnam. in the global trade pattern should be China has to date signed bilateral decided by adjustments in the indus- and multilateral free trade agree- trial structure and through product ments with seven TPP members. competitiveness in global -

Soho China Limited (410 HK)-OW: Decent Progress but Shanghai

Company report FIG Real Estate Equity – China Soho China Limited (410 HK) Overweight OW: Decent progress but Shanghai faces more Target price (HKD) 6.50 competition Share price (HKD) 5.36 Forecast dividend yield (%) 5.8 Decent leasing progress underpinned by favourable office Potential return (%) 27.1 market dynamics in Beijing and Shanghai Note: Potential return equals the percentage difference between the current share price and Net gearing set to increase further, absent an asset sale the target price, plus the forecast dividend yield Dec 2014 a 2015 e 2016 e HSBC EPS 0.34 0.23 0.14 Maintain OW with a new TP of HKD6.50 (vs. HKD6.60) HSBC PE 12.6 18.9 31.3 Performance 1M 3M 12M Absolute (%) -1.7 -7.9 -10.1 Headline miss in FY14 results; other line items were in-line. FY14 core profit of Relative^ (%) -0.9 -8.0 -30.1 RMB1,778m is down 60% y-o-y, 11% and 17% below our and consensus estimates, Note: (V) = volatile (please see disclosure appendix) mainly due to a 9% miss in property development revenue. Core profit margin of 29% was slightly below our forecast of 30%. Final dividend of RMB0.13 and the full year 6 March 2015 dividend of RMB0.25 remain flat y-o-y. The implied dividend yield is 5.8%, consistent Michelle Kwok* with yield levels that SOHO has been paying over the past five years. Analyst The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Some encourage leasing progress, but much work needs to be done in 2015. -

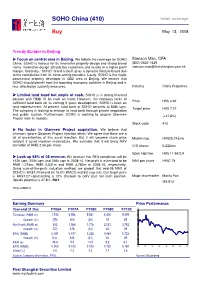

SOHO China (410) Initial Coverage

SOHO China (410) Initial coverage Buy May 13, 2008 Trendy Builder in Beijing Focus on central area in Beijing. We initiate the coverage for SOHO Samson Man, CFA China. SOHO is famous for its innovative property design and strong brand (852)-2532-1539 name. Innovative design attracts the customers and results in a higher profit [email protected] margin. Secondly, “SOHO” brand is built up as a dynamic lifestyle brand due to the contribution from its trend-setting founders. Lastly, SOHO is the major commercial property developer in CBD area in Beijing. We believe that SOHO should benefit from the booming economic activities in Beijing and is less affected by austerity measures. Industry China Properties Limited land band but ample of cash. SOHO is in strong financial position with RMB 15 bn cash on hand. However, the company lacks of Price HK$ 4.92 sufficient land bank for its coming 5 years development. SOHO is keen on land replenishment. At present, land bank of SOHO amounts to 838k sqm. Target price HK$ 7.27 The company is looking to enlarge its land bank through private negotiation and public auction. Furthermore, SOHO is working to acquire Qianmen (+47.8%) Project from its founder. Stock code 410 No factor in Qianmen Project acquisition. We believe that investors ignore Qianmen Project injection effect. We agree that there are a lot of uncertainties of this asset injection. But it will become share price Market cap. HK$25,743mn catalyst if asset injection materializes. We estimate that it will bring NAV accretion of RMB 2.06 per share. -

NBA 6400 Doing Business in China (17540) Class Meetings: Mon & Wed 11:55Am - 1:10Pm (Jan 22 - Mar 12, 2019) Location: Breazzano Family Center 221

NBA 6400 Doing Business in China (17540) Class meetings: Mon & Wed 11:55am - 1:10pm (Jan 22 - Mar 12, 2019) Location: Breazzano Family Center 221 Instructor: Chris Marquis Email: [email protected] Sage Hall 363 Revised February 24, 2019 (subject to change) CLASS OVERVIEW In today’s increasingly globalized economy, understanding the world’s second largest economic superpower is essential for global success. This course is designed for students who are interested in working in and with businesses from China as well as future business leaders who wish to develop a general understanding of Chinese business practices. The course examines the many different types of business—private and public, Chinese and foreign—and the institutions that have and will define China’s economic trajectory and its role in the global economy. These include the state-owned firms that have been the foundation of modern China’s economy that dominating infrastructure and finance industries; the large, new private businesses that have emerged in many industries and are challenging the state sector; and the foreigners, whose ideas about “the China market” have both focused and clouded their vision. The course will also address key elements of the current political and economic situation in China. As China rebalances from an investment-driven and polluting-for-development to a consumption-, innovation-, and sustainability-driven economy, what are the opportunities for entrepreneurs? How do businesses manage the political challenges posed by the state system (the Communist -

Accelerated Scale Expansion to Further Stretch Balance Sheet

September 20, 2016 COMMENT Sunac China Holdings (1918.HK) HK$5.87 Equity Research Accelerated scale expansion to further stretch balance sheet News On Sept 18, Sunac announced a potential transaction with Legend (3396.HK, Sept 19 close HK$20; Neutral; covered by Simon Cheung) to acquire 42 property projects in 16 cities with total unsold GFA of 7.3mn sqm for consideration of Rmb13.8bn, pending approval from shareholders of the companies. The consideration is comprised of Rmb3.6bn equity interest in companies that hold interests in the properties and assumption of Rm10.2bn of external debt, shareholders’ loan and accrued but unpaid interest. It will be paid in cash including Rmb5.5bn in 2016 and the rest in 2017 if the deal completes in early 2017 according to mgmt. Analysis As we highlighted in "Sunac China: Downgrade to Neutral on weak profitability and rising leverage" (Aug 31, 2016), we expect Sunac to continue its aggressive scale expansion at the expense of lower margins and higher leverage, and the proposed transaction comes at an even more accelerated pace than we anticipated. Based on the disclosed details, we note: 1) If completed, Sunac’s attributable landbank size will increase by 18% to GFA36.5mn sqm from 1H16 and geographic coverage will expand by 8 new cities to a total of 35 cities while the share of its attributable land bank in tier- 1/2/3 cities will change to 9%/67%/24% from 10%/75%/15% as of 1H16 (Ex. 1). 2) Stripping out one-off gains, the assets generated c.Rmb0.2bn net profit in 2015 (equivalent to 6% of Sunac's 2015 core profit) due to a deceleration in sales and margin slippage as per Simon Cheung. -

China Property Sector

China / Hong Kong Industry Focus China Property Sector Refer to important disclosures at the end of this report DBS Group Research . Equity 19 Apr 2021 Spotlight on future land supply • Solid sales growth momentum sustained with strong HSI: 28,970 potential to ink another year of record-high sales • Developers poised to meet their 2021 targets ANALYST Jason LAM +852 3668 4179 [email protected] • Future land supply and new starts as keys to watch for Danielle WANG CFA, +852 3668 4176 [email protected] • Sector top picks: Vanke, COLI, CIFI and Logan Ken HE CFA, +86 21 3896 8221 [email protected] Solid performance in 1Q21; strong potential for another year of Ben Wong [email protected] record-high residential sales. Residential sales in Mar rose 63% y-o-y (or 44% vs Mar-19) on the back of a 38% (or 19% vs Mar- Recommendation & valuation 19) increment in residential GFA sold and 19% (or 21% vs Mar- 19) rise in residential ASP, marking another solid month of FY22F physical market performance. We believe the market is well- Target Price Price Rec Mkt Cap PE poised to post another record-high sales value this year – as it HK$ HK$ US$bn x will likely attain 2020’s level even if the market records a 12.5% y- o-y decline for the remaining nine months. China Overseas Developers well on track to achieve their 2021 targets. Presales 20.15 25.70 BUY 28.4 4.0 (688 HK) growth of 30 listed developers we track on a weighted-average China Vanke 'H' 28.25 45.56 BUY 49.9 5.3 basis remained strong at 47% y-o-y (or +33% vs Mar 2019) in (2202 HK) Mar (Feb-21: 144%), as compared to their c.10% weighted Logan Property 12.50 16.44 BUY 8.9 3.5 average presales target for 2021. -

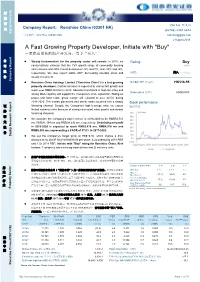

A Fast Growing Property Developer, Initiate with "Buy"

股 票 研 [Table_Title] Van Liu 刘斐凡 Company Report: Ronshine China (03301 HK) 究 (86755) 2397 6672 Equity Research 公司报告: 融信中国 (03301 HK) [email protected] 2 August 2018 A[Table_summary] Fast Growing Property Developer, Initiate with "Buy" 一家快速增长的地产开发商,首予“买入” 公 Steady fundamentals for the property sector will remain. In 2018, we Rating:[Table_Rank] Buy 司 conservatively estimate that the YoY growth range of commodity housing Initial sales amount and GFA should be between -5% and 0%, and -10% and -5%, 报 respectively. We also expect stable ASP, decreasing saleable areas and 评级: 买入 (首次覆盖) 告 steady investment. Company Report Ronshine China Holdings Limited ("Ronshine China") is a fast growing 6[Table_Price]-18m TP 目标价 : HK$16.55 property developer. Contracted sales is expected to extend fast growth and reach over RMB120.0 bn in 2018. Abundant land bank in high-tier cities and Share price 股价: HK$9.000 strong M&A capacity will support the Company's scale expansion. Riding on proper unit land costs, gross margin will rebound to over 22.5% during 告 2018-2020. The shares placement and senior notes issuance hint a steady Stock performance 证 financing channel. Despite the Company's high leverage ratio, we expect 股价表现 报 limited solvency risks because of strong contracted sales growth and steady 券 [Table_QuotePic] 究 financing channels. 研 研 We estimate the Company’s total revenue in 2018-2020 to be RMB58,741 究 mn, RMB81,154 mn and RMB98,033 mn, respectively. Underlying net profit 券 in 2018-2020 is expected to reach RMB3,476 mn, RMB4,976 mn and 报 RMB6,086 mn, representing a CAGR of 67.0% in 2017-2020. -

SOHO China Limited / Annual Report 2015

Stock Code: 410 SOHO China Limited / Annual Report 2015 SOHO CHINA LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2015 SOHO CHINA The board (the “Board”) of directors (the “Directors”) of SOHO China Limited (the “Company”, “We” or “SOHO China”) is pleased to announce the audited consolidated annual results of the Company and its subsidiaries (collectively, the “Group”) for the year ended 31 December 2015 (the “Year” or the “Period”), which had been prepared in accordance with the Hong Kong Financial Reporting Standards issued by Hong Kong Institute ooff CCertifiedertified Public Accountants and the relevant provisions ooff the Rules GGoverningoverning the Listing of SSecuritiesecurities ((thethe ““ListingListing Rules”)Rules”) on The StockStock Exchange ooff Hong Kong Limited (the(the “Stock“Stock Exchange”).Exchange”). The 20120155 audited consolidated annual results ooff the GGrouproup had been reviewed by the audit committee ooff the CCompanyompany (“(“AuditAudit CCommittee”)ommittee”) and approved by the Board on 8 March 20162016.. During the Period, the GroupGroup achieved a turnover ofof approximately RMB995RMB995 million, including RMB1,052RMB1,052 million ffromrom property leasing, representing an increase ooff approximately 1148%48% compared with the same period in 2012014.4. The gross proprofitfit margin ooff the GroupGroup during the year was approximately 7474%.%. Net profitprofit attributable to equity shareholders ooff the CCompanyompany fforor the Period was approximately RMB5RMB53838 million, representing a decrease ooff approximately 887%7% compared to 2012014.4. CCoreore net proprofitfit ((excludingexcluding net valuation gains on investment propertiesproperties)) attributable to equity shareholders ooff the CCompanyompany fforor the Period was approximately RMB4RMB42323 million, which decreased by approximately 776%6% ffromrom 2012014.4. The core net proprofitfit margin during the Period was approximately 442%.2%. -

Wang Jianlin Wanda Group

10 Property.FIN.qxp_Layout 1 13/9/16 5:41 pm Page 113 Week in China China’s Tycoons Property Wang Jianlin Wanda Group the “football mayor” while Dalian Wanda became a household name in China thanks to its all-conquering football team which “My dominated the Chinese league in the 1990s. philosophy is always the Big break same: be close In 1991, Wanda was one of the state entities with the picked to become a ‘pilot’ joint stock firm. government, Wang got the controlling shareholder of and distance Wanda, which then began to expand beyond myself from Liaoning. politics” Wang came up with the idea of the Wanda Plaza: mega residential and commercial complexes. Local governments welcomed these huge projects with land and other incentives By late 2015 Wanda had 133 Wanda Plazas and 84 hotels nationwide with total leasable area of 26 million square metres. Going global At the apex of Chinese politics stands a group In 2012 Bo Xilai was arrested and lost out to Xi of elites known as the hongerdai, or children Jinping, another hongerdai, in the race to or grandchildren of the revolutionary leaders become China’s supreme leader. It didn’t seem who helped the Communist Party to seize to have affected Wang. power in 1949. Wang is among the blue bloods Indeed, it was after 2012 that Wang began to (“red bloods” may be politically more spend aggressively overseas. His trophy buys appropriate): his father had taken part in and include London properties, UK yacht maker survived the Red Army’s Long March.