Blyden's Philosophy and Its Impact on West African Intellectuals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

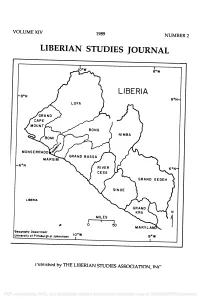

Liberian Studies Journal

VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL r 8 °W LIBERIA -8 °N 8 °N- MONSERRADO MARGIBI MARYLAND Geography Department 10 °W University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown 8oW 1 Published by THE LIBERIAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION, INC. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Cover map: compiled by William Kory, cartography work by Jodie Molnar; Geography Department, University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL Editor D. Elwood Dunn The University of the South Associate Editor Similih M. Cordor Kennesaw College Book Review Editor Dalvan M. Coger Memphis State University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Bertha B. Azango Lawrence B. Breitborde University of Liberia Beloit College Christopher Clapham Warren L. d'Azevedo Lancaster University University of Nevada Reno Henrique F. Tokpa Thomas E. Hayden Cuttington University College Africa Faith and Justice Network Svend E. Holsoe J. Gus Liebenow University of Delaware Indiana University Corann Okorodudu Glassboro State College Edited at the Department of Political Science, The University of the South PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor CONTENTS THE LIBERIAN ECONOMY ON APRIL 1980: SOME REFLECTIONS 1 by Ellen Johnson Sirleaf COGNITIVE ASPECTS OF AGRICULTURE AMONG THE KPELLE: KPELLE FARMING THROUGH KPELLE EYES 23 by John Gay "PACIFICATION" UNDER PRESSURE: A POLITICAL ECONOMY OF LIBERIAN INTERVENTION IN NIMBA 1912 -1918 ............ 44 by Martin Ford BLACK, CHRISTIAN REPUBLICANS: DELEGATES TO THE 1847 LIBERIAN CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION ........................ 64 by Carl Patrick Burrowes TRIBE AND CHIEFDOM ON THE WINDWARD COAST 90 by Warren L. -

The Speculative Fiction of Octavia Butler and Tananarive Due

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Digital Commons@Wayne State University Wayne State University DigitalCommons@WayneState Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2010 An Africentric Reading Protocol: The pS eculative Fiction Of Octavia Butler And Tananarive Due Tonja Lawrence Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Recommended Citation Lawrence, Tonja, "An Africentric Reading Protocol: The peS culative Fiction Of Octavia Butler And Tananarive Due" (2010). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 198. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. AN AFRICENTRIC READING PROTOCOL: THE SPECULATIVE FICTION OF OCTAVIA BUTLER AND TANANARIVE DUE by TONJA LAWRENCE DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2011 MAJOR: COMMUNICATION Approved by: __________________________________________ Advisor Date __________________________________________ __________________________________________ __________________________________________ __________________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY TONJA LAWRENCE 2011 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To my children, Taliesin and Taevon, who have sacrificed so much on my journey of self-discovery. I have learned so much from you; and without that knowledge, I could never have come this far. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply grateful for the direction of my dissertation director, help from my friends, and support from my children and extended family. I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my dissertation director, Dr. Mary Garrett, for exceptional support, care, patience, and an unwavering belief in my ability to complete this rigorous task. -

From Malcolm Little to El Hajj Malik El-Shabazz Quote: I Am All That I Have Been

THE MULTIFARIOUS JIHADS OF MALCOLM X: FROM MALCOLM LITTLE TO EL HAJJ MALIK EL-SHABAZZ QUOTE: I AM ALL THAT I HAVE BEEN. EL HAJJ MALIK EL-SHABAZZ, 1964 A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Professional Studies in Africana Studies by Keisha A. Hicks August 2009 © 2009 Keisha A. Hicks ABSTRACT Malcolm X is one of the most iconoclastic persons in the African American political and intellectual traditions. The challenge in performing the research for this thesis, was to find a way to examine the life of Malcolm X that is different from the scholarly work published to date. I contemplated on what might be the most impactful Islamic concept that has influenced American dominant culture during the past twenty years. The critical lens I chose to utilize is the Islamic cultural practice of Jihad. The attraction for me was juxtaposing various concepts of Jihad, which is most closely aligned with the manifestations of Malcolm’s faith as a Muslim. By using Jihad as my critical lens for analyzing his life and speeches I hope to present an even greater appreciation for Malcolm X as a person of deep faith. The forms of Jihad I will apply for contextual analysis are Jihad bin Nafs {Jihad of the Heart}, Jihad bil Lisan {Jihad of the Tongue}, and Jihad bin Yad {Jihad of Action}. Having read the Autobiography several times at different stages during my academic career I thought I had gained a good understanding of Malcolm X’s life. -

Selected Black Critiques of Western Education 1850-1933

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1985 The politics of knowledge : selected black critiques of western education 1850-1933. P. Oaré Dozier University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Dozier, P. Oaré, "The politics of knowledge : selected black critiques of western education 1850-1933." (1985). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 4155. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/4155 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POLITICS OF KNOWLEDGE: SELECTED BLACK CRITIQUES OF WESTERN EDUCATION 1850-1933 A Dissertation Presented By P. OARE DOZIER Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION February 1985 School of Education P. Oare Dozier All Rights Reserved THE POLITICS OF KNOWLEDGE: SELECTED BLACK CRITIQUES OF WESTERN EDUCATION 1850-1933 A Dissertation Presented By P. OARE DOZIER Approved as to style and content by: cy\ s Dr. Asa Davis, Member Mario D. Fantim Dean School of Education i i i To my pillars of support Cita and Pop-Pop, and my sheltering arms. Kamayu, Tasmia, and Asegun ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A complete dissertation is never the product of any one person. In this case there are many people that I am indebted to. First and foremost, my family gets the singular prize for lovingly supporting me through this. -

DECOLONIZING BLYDEN by ANTAR FIELDS

DECOLONIZING BLYDEN by ANTAR FIELDS (Under the Direction of Diane Batts Morrow) ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to “decolonize” Edward W. Blyden, educator, diplomat, and black nationalist, by isolating three of his most controversial and contradicting ideologies—race, colonization, and religion—within the context of his “multiple consciousness”: the Negro, the American, and the African. Historians criticize Blyden for his disdain for mulattoes, pro-colonization and pro-imperialist stance, and his idealistic praise of Islam. The inaccuracy of these ideologies has received considerable attention by Blyden historians. The objective of this study is not to add to the criticism but to demystify and deconstruct Blyden’s rhetoric by analyzing the substance and intent of his arguments. Concentrating on his model for a West African nation-state allows more insight into the complexities of his thought. Studying the historical environment in which Blyden formulated his ideologies provide a more in-depth analysis into how his multiple consciousness evolved. INDEX WORDS: American Colonization Society, Edward W. Blyden, Colonialism, Colonization Movement, Colorism, Emigration, Liberia, Multiple Consciousness DECOLONIZING BLYDEN by ANTAR FIELDS B.A., Augusta State University, 2003 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2005 © 2005 Antar Fields All Rights Reserved DECOLONIZING BLYDEN by ANTAR FIELDS Major Professor: Diane Batts -

Pan-African History: Political Figures from Africa and The

Pan-African History Pan-Africanism, the perception by people of African origins and descent that they have interests in common, has been an important by-product of colonialism and the enslavement of African peoples by Europeans. Though it has taken a variety of forms over the two centuries of its fight for equality and against economic exploitation, commonality has been a unifying theme for many Black people, resulting for example in the Back-to-Africa movement in the United States but also in nationalist beliefs such as an African ‘supra-nation’. Pan-African History brings together Pan-Africanist thinkers and activists from the Anglophone and Francophone worlds of the past two hundred years. Included are well-known figures such as Malcolm X, W.E.B. Du Bois, Frantz Fanon, Kwame Nkrumah, and Martin Delany, and the authors’ original research on lesser-known figures such as Constance Cummings-John and Dusé Mohamed Ali reveals exciting new aspects of Pan-Africanism. Hakim Adi is Senior Lecturer in African and Black British History at Middlesex University, London. He is a founder member and currently Chair of the Black and Asian Studies Association and is the author of West Africans in Britain 1900–1960: Nationalism, Pan-Africanism and Communism (1998) and (with M. Sherwood) The 1945 Manchester Pan-African Congress Revisited (1995). Marika Sherwood is a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London. She is a founder member and Secretary of the Black and Asian Studies Association; her most recent books are Claudia Jones: A Life in Exile (2000) and Kwame Nkrumah: The Years Abroad 1935–1947 (1996). -

And Others Africa South Of

DOCUMENT RESUME ED C50 000 48 SO 001 213 AUTHOR Duignan, Peter; And Others TITLE Africa South of the Sahara: A Bibliography for Undergraduate Libraries. INSTITUTION National Council of Associations for International Studies, Pittsburgh, Pa.; New York State Education Dept., Albany. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DREW), Washington, D.C. REPORT NO OPUB-12 BUREAU NO BR-5-0931 PUE LATE 71 NCTE 127p. AVAILABLE FROM Foreign Area Materials Center, 11 West 42nd Street, New York, New York ($8.95) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$E.58 DESCRIPTORS African Culture, African History, Area Studies, Bibliographies, Higher Education, *Library Collections, Library Materials, *Library Material Selection, *Social Sciences, *Undergraduate Study IDENTIFIERS *Africa, ESEA Title 4 ABSIRACI Library collections are generally ill equipped tc effectively sin:port foreign area students. This bibliography, one of a series on "neglected" foreign areas, attempts to provide guidelines for libraries in meeting these resources needs. Selection of entries was made according to the following guidelines: 1)few works in languages other than English; 2)emphasis on books published in the last 25 years, except for classica works; 3)few government documents; and, 4)an attempt to balance source books and secondary works, while covering all disciplines. Arrangement of entries is by broad geographic category, with subsections based on type of publication (bibliography, reference bcck, journal, general book) and subject area (history and archaeology, philosophy and religion, art and architecture etc.). Each entry is graded as to its degree of necessity for undergraduate collections, from books that should be purchased whether or not any courses on the area are taught, tc books necessary for an undergraduate area studies program. -

The African Personality Or the Dilemma of the Other and the Self in the Philosophy of Edward W

ASIAN AND AFRICAN STUDIES, 7, 1998, 2, 162175 THE AFRICAN PERSONALITY OR THE DILEMMA OF THE OTHER AND THE SELF IN THE PHILOSOPHY OF EDWARD W. BLYDEN, 18321912* Viera PAWLIKOVÁ-VILHANOVÁ Institute of Oriental and African Studies, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Klemensova 19, 813 64 Bratislava, Slovakia The second stage of Europes contact with Africa beginning in the late eighteenth century and continuing throughout the nineteenth into the twentieth century started the long and difficult problem of the identity of Africa and of the Africans which is vital even today. During this period of Afro-European contact Africans were repeatedly confronted with the questions of change and choice as they tried to come to terms with the new world of an expanding Western civilization which was in process of moulding the world in its image. One man in nineteenth- century Africa who tried to see the problem in its entirety was Edward W. Blyden (1832 1912), a West-Indian of pure African descent who during his active career in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Lagos summed up his political and cultural theories, based on a rich fund of living experience and profound study, in his concept of African personality. European contact with West Africa goes back five centuries, but the influ- ence of Europe over this period has varied enormously. If we skip the first, the longest and in its effects entirely negative span of time which covered three cen- turies of African history and was dominated by the slave trade, it was the second stage of Europes contact with Africa beginning in the late eighteenth century and continuing throughout the nineteenth into the twentieth century, which actu- ally started the problem of the identity of Africa and of the Africans. -

334 Marika Sherwood Henry Sylvester Williams's Was One of The

334 book reviews Marika Sherwood Origins of Pan-Africanism: Henry Sylvester Williams, Africa, and the African Diaspora. London: Routledge, 2010. xvi + 354 pp. (Cloth us$125.00) Henry Sylvester Williams’s was one of the most unlikely and remarkable lives, even for a child of the African diaspora. Born in Barbados in 1867 (not Trinidad in 1869, as previously thought), he accompanied his working-class parents to Trinidad, where he grew up in Arouca with five younger siblings. He barely acquired a secondary education, but in subsequent years became not only a qualified barrister in London, but also the first black man admitted to the bar in Cape Town, one of the first two elected black borough councilors in London, the publisher and editor of a monthly magazine, the author of a booklet, the representative—at the seat of the British Empire—of various Southern and West African political organizations and pressure groups, and the convener of the first Pan-African Conference (London 1900), three years after he had founded the African Association, comprising continental and diaspora Africans. He died in Trinidad in 1911 at age 44, less than three years after returning home from his long sojourn abroad. He was long forgotten and under-appreciated after his death, even in Trini- dad and even by people who should have known better. The self-serving and prolific W.E.B. Du Bois, who attended the 1900 conference, barely mentions Williams. C.L.R. James (Williams’s countryman), “that intellectual prodigy and indefatigable delver into the Caribbean past, … seemed somewhat uncertain exactly what Williams had done before and after July 1900” (Hooker 1975:2). -

The Response of African Americans to the Nigerian Civil War, 1967-1970

‘Black America Cares’: The Response of African Americans to the Nigerian Civil War, 1967-1970 By James Austin Farquharson B.A, M.A (Research) A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Education and Arts Australian Catholic University 7 November 2019 Statement of Originality This thesis contains no material that has been extracted in whole or in part from a thesis that I have submitted towards the award of any other degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgment in the main text of the thesis. ‘Black America Cares’: The response of African Americans to the Nigerian Civil War, 1967-1970 Abstract Far from having only marginal significance and generating a ‘subdued’ response among African Americans, as some historians have argued, the Nigerian Civil War (1967-1970) collided at full velocity with the conflicting discourses and ideas by which black Americans sought to understand their place in the United States and the world in the late 1960s. Black liberal civil rights leaders leapt to offer their service as agents of direct diplomacy during the conflict, seeking to preserve Nigerian unity; grassroots activists from New York to Kansas organised food-drives, concerts and awareness campaigns in support of humanitarian aid for Biafran victims of starvation; while other pro-Biafran black activists warned of links between black ‘genocide’ in Biafra and the US alike. This thesis is the first to recover and analyse at length the extent, complexity and character of such African American responses to the Nigerian Civil War. -

Americo-Liberians and the Transformative Geographies of Race

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--History History 2013 Whiteness in Africa: Americo-Liberians and the Transformative Geographies of Race Robert P. Murray University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Murray, Robert P., "Whiteness in Africa: Americo-Liberians and the Transformative Geographies of Race" (2013). Theses and Dissertations--History. 23. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/23 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--History by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. I retain all other ownership rights to the copyright of my work. -

CONTENTS Part I Africa in the Configurations of Knowledge Part II

Copyrighted material – 9781137495167 CONTENTS List of Illustrations vii Preface ix Introduction 1 One An Emerging Biography 17 Part I Africa in the Configurations of Knowledge Two African-Centered Conceptualization 43 Three Pluralism and Religious Tolerance 59 Four Postulates on the African State 77 Five Axioms of African Migrations and Movements 85 Part II The Yoruba in the Configurations of Knowledge Six A Mouth Sweeter than Salt : A Fractal Analysis 99 Seven Yoruba Gurus and the Idea of Ubuntugogy 121 Eight Pragmatic Linguistic Analysis of Isola 137 Part III The Value of Knowledge: Policies and Politics Nine The Power of African Cultures : A Diegetic Analysis 155 Ten African Peace Paradigms 185 Eleven Pan-African Notions 203 Twelve Using E-clustering to Learn and Teach about Toyin Falola 217 Conclusion: An Interpretative Overview 235 Copyrighted material – 9781137495167 Copyrighted material – 9781137495167 vi Contents Appendix: Notation Conventions 241 List of Works by Toyin Falola 243 Notes 249 Bibliography 277 Index 293 Copyrighted material – 9781137495167 Copyrighted material – 9781137495167 TOYIN FALOLA AND AFRICAN EPISTEMOLOGIES Copyright © Abdul Karim Bangura, 2015. All rights reserved. First published in 2015 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN® in the United States—a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Where this book is distributed in the UK, Europe and the rest of the world, this is by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries.