Soils in Tug Hill, NY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oneida Lake – Lock 22 to Lock 23 NOAA Chart 14788

BookletChart™ Oneida Lake – Lock 22 to Lock 23 NOAA Chart 14788 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Included Area Published by the Lyons, the canal crosses the Genesee River. From the intersection, a 3.2- mile section of the Genesee River has been improved to provide access National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration from the canal to Rochester. A dam on the Genesee River 7 miles National Ocean Service downstream of the canal precludes navigable access to Lake Ontario. Office of Coast Survey The Erie Canal, from Waterford to Tonawanda, has 34 locks. At Waterford, a flight of 5 locks ascends 168.8 feet from the pool above www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov Troy Lock and Dam around Cohoes Falls to the Mohawk River, thence 14 888-990-NOAA locks ascend the Mohawk Valley 236 feet to the summit level near Rome, NY, thence 3 locks descend 57 feet to Three Rivers, NY, at the What are Nautical Charts? junction with Oswego Canal, and thence 12 locks ascend 201 feet to the Niagara River. Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and efficient navigation. Chart carriage is mandatory on the commercial ships that carry America’s commerce. They are also used on every Navy and Coast Guard ship, fishing and passenger vessels, and are widely carried by recreational boaters. What is a BookletChart ? This BookletChart is made to help recreational boaters locate themselves on the water. -

Lake Ontario Maps, Facts and Figures

Lake Ontario maps, facts and figures A project by the FINGER LAKES-LAKE ONTARIO WATERSHED PROTECTION ALLIANCE and NEW YORK SEA GRANT 1. Origins of Lake Ontario Direct Drainage Basin 2. Population by Census Block Groups 3. Detailed Surface Water New York’s Lake Ontario . shown in maps, facts & figures Lake Ontario, the 14th largest lake in the world, is the smallest of the Great 4. Topography Lakes. Bordered to the north by Ontario, Canada, and to the south by New York State, it is the smallest in surface area, fourth among the Great Lakes in maximum depth, but second only to Lake Superior in average depth. The basin land area is largely rural with a significant forested and Lake Ontario at a glance 5. Land Use Types agricultural portion. The Lake is nestled between the mighty Niagara River Lake Ontario is the 14th largest lake in the world. to the west...and the picturesque St. Lawrence River Valley to its east. Length: 193 mi / 311 km Width: 53 mi / 85 km Almost one-third of the land area of New York State drains Published by Finger Lakes-Lake Ontario Watershed Protection Alliance (FLLOWPA) Average depth: 283 ft / 86 m 6. Wastewater Treatment Plants and New York Sea Grant. into Lake Ontario, making the wise use and management of Maximum depth: 802 ft / 244 m All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval natural resources vital to the long-term sustainability of the system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, 3 3 photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. -

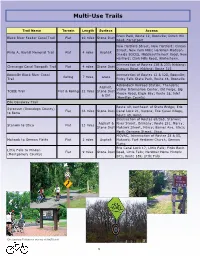

Multi-Use Trails

Multi-Use Trails Trail Name Terrain Length Surface Access Erwin Park, Route 12, Boonville; Dutch Hill Black River Feeder Canal Trail Flat 10 miles Stone Dust Road, Forestport New Hartford Street, New Hartford; Clinton Street, New Y ork Mills; Herkimer- Madison- Philip A. Rayhill Memorial T rail Flat 4 miles Asphalt Oneida BOCES, Middlesettlement Road, New Hartford; Clark Mills Road, Whitestown. Intersection of Routes 12B & 233; Kirkland; Chenango Canal Towpath Trail Flat 4 miles Stone Dust Dugway Road, Kirkland; Route 315, Boonville Blac k River Canal Intersection of Routes 12 & 12D, Boonville; Rolling 7 miles Grass Trail Pixley Falls State Park, Route 46, Boonville Adirondack Railroad Station, Thendara; Asphalt, Visitor Information Center, Old Forge; Big T OBIE T rail Flat & Rolling 12 miles Stone Dust Moose Road, Eagle Bay; Route 28, Inlet & Dirt (Hamilton County) Erie Canalway T rail Route 49, northeast of State Bridge; Erie Syracuse (Onondaga County) Flat 36 miles Stone Dust Canal Lock 21, Verona; Erie Canal Village, to Rome Rout e 49, Rome Intersection of Routes 69/365, Stanwix; Asphalt & River Street, Oriskany; Route 291, Marcy; Stanwix to Utic a Flat 13 miles Stone Dust Mohawk Street, Marcy; Barnes Ave, Utica; North Genesee Street, Utica MOVAC, Intersection of Routes 28 & 5S, Mohawk to German Flatts Flat 2 miles Asphalt Mohawk; Fort Herkimer Churc h, German Flatts Erie Canal Lock 17, Little Falls; Finks Basin Little Falls to Minden Flat 9 miles Stone Dust Road, Little Falls; Herkimer Home Historic (Montgomery County) Site, Route 169, Little Falls Erie Canalway Trail photos courtesy of HOCTS staff 6 Black River Feeder Canal Trail See Maps E and E-1 The approximately 10-mile Black River Feeder Canal trail is part of a New York State Canal Cor- poration improvement project to rehabilitate the towpath that follows the Black River Feeder Ca- nal. -

Chartbook, 2018 Update Growth by Region and Practice, 2013–2018

New York PCMH Chartbook, 2018 Update Growth by Region and Practice, 2013–2018 Introduction This chartbook accompanies a UHF issue brief (Patient-Centered Medical Homes in New York, 2018 Update: Drivers of Growth and Challenges for the Future) reviewing broad trends in the adoption of the Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) model in New York, noting the remarkable growth in the number of PCMH clinicians between 2017 and 2018—and the contribution of Performing Provider Systems (PPSs) participating in the state’s Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) program to that growth. Additionally, the brief describes variation in PCMH adoption by region and type of primary care practice. This chartbook more fully describes that variation. Data Sources The Office of Quality and Patient Safety (OQPS) within the New York State Department of Health (DOH) receives monthly data files from the National Council on Quality Assurance (NCQA) with information on all practices in New York State that have achieved NCQA PCMH recognition, and on the clinical staff (physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician’s assistants) working there. Each year for the past six years, OQPS has shared some of that information with UHF, which then analyzes the adoption of the PCMH model by region and practice type. The Regions As part of a 2015 initiative, the DOH divided the state into 11 regions (see Exhibit 1), funding regional planning agencies (Population Health Improvement Programs, or PHIPs) to develop plans for improving the health of their residents. Before 2015, UHF used New York’s insurance rating regions to analyze PCMH growth; since then we have used the PHIP regions. -

Welcome to The

Welcome to the June 3, 2015 8:00 am — 1:00 pm at the The Hayloft at Moonshine Farm* 6615 Buneo Rd. Port Leyden, NY 13343 Organized and hosted by the Lewis Sponsored by 5 Finger Lakes Lake 1:00 - 5:00 PM and Jefferson County Soil and Water Ontario Watershed Protection Afternoon Field Trip Conservation Districts, NYS Tug Hill Alliance Counties: Lewis, Jefferson, Sponsored by the Commission and the New York State Herkimer, Oneida and Hamilton Department of Environmental Beaver River Advisory Council Conservation Region 6. 8:00 am - 8:20 am Sign in and Refreshments 8:20 am - 8:30 am Welcome and Introduction ~ Nichelle Billhardt, Lewis County Soil and Water Conservation District Morning Session Invasive Species Watercraft Inspection Program ~ Dr. Eric Holmlund, Watershed Stewardship Program 8:30 am - 9:20 am at the ADK Watershed Institute of Paul Smith’s College Project Updates ~ Jennifer Harvill, NYS Tug Hill Commission; Emily Sheridan, NYS DEC; Frank Pace, 9:20 am - 9:50 am Lewis County Eco Dev & Planning; Mike Lumbis, City of Watertown Planning and others Community Resiliency & Green Infrastructure - Green Innovation Grant Program ~ Tana Bigelow, 9:50 am - 10:40 am Green Infrastructure Coordinator, Environmental Facilities Corporation 10:40 am - 10:55 am Break Stormwater MS4 Update ~ Christine Watkins, Jefferson County SWCD & Katie Malinowski, NYS Tug 10:55 am - 11:10 am Hill Commission Nutrient Management 101 ~ Karl Czymmek, Nutrient/CAFO/Environmental Management, Cornell 11:10 am - Noon University Noon Lunch - Soup, Salad, Wraps and Deli -

Oneida Lake, Causing New York to Add the Lake to Its Clean Water Act Section 303(D) List in 1998

Section 319 NONPOINT SOURCE PROGRAM SUCCESS STORY Agricultural Environmental ManagementNew Projects Reduce York Phosphorus in Lake Waterbody Improved Algal blooms and rooted vegetation impaired primary recre- ation and aquatic life beneficial uses of New York’s Oneida Lake, causing New York to add the lake to its Clean Water Act section 303(d) list in 1998. Excess nutrients, specifically phosphorus, from agricultural and urban/suburban runoff caused the growth of algal blooms in the lake. Implementing best management prac- tices (BMPs) such as barnyard runoff management systems, silage leachate control sys- tems, manure storage systems, and nutrient and sediment control systems successfully reduced phosphorus loads to Oneida Lake. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation’s (DEC) has proposed Oneida Lake for delisting in 2008 because data show steady declines in nutrient enrichment (phosphorus levels) and indicate that the lake sup- ports designated uses related to nutrient enrichment. Problem Oneida Lake, while not recognized as one of the Finger Lakes, is sometimes referred to as the “Thumb of the Finger Lakes.” It is the largest lake entirely within New York State. It encompasses 51,000 acres and drains more than 2,300 miles of streams. The Oneida Lake watershed is in the Oswego-Seneca-Oneida Rivers Drainage Basin, which drains to Lake Ontario (Figure 1). It also serves as one of the links in the Erie Canal. The Oneida Lake watershed (approximately 1,364 square miles) contains portions of six counties, 69 municipalities and has a population of 262,000. The lake is approximately 21 miles long, 5 miles wide and 22 feet deep. -

Regional Planning Consortium QUARTER THREE UPDATE JULY 1 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2020 Table of Contents

Regional Planning Consortium QUARTER THREE UPDATE JULY 1 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2020 Table of Contents RPC Mission & Purpose 2020 RPC Areas of Focus ◦ VBP/Managed Care: PC Integration ◦ SDOH/Care Transitions & Co- Occurring Integration ◦ Peer/Behavioral Health Workforce ◦ Children & Families Capital Region Central NY Finger Lakes Long Island Mid-Hudson Mohawk Valley North Country Southern Tier Tug Hill Western NY 2 RPC Mission & Purpose Who We Are: The Regional Planning Consortium (RPC) is a network of 11 regional boards, community stakeholders, and Managed Care Organizations that work closely with our State partners to guide behavioral health policy in the regions to problem-solve and develop lasting solutions to service delivery challenges. RPC Mission Statement: The RPC is where collaboration, problem solving and system improvements for the integration of mental health, addiction treatment services and physical healthcare can occur in a way that is data informed, person and family centered, cost efficient and results in improved overall health for adults and children in our communities. About this Report: The content of this Report targets Quarter 3 (Q3) (July 1 – September 30, 2020) activities conducted by the rest-of-state RPC by Region. Click HERE to return to Table of Contents 3 2020 RPC Areas of Focus In Q3, from a statewide perspective, the RPC continued to develop our four Areas of Focus in 2020. In cooperation with the impactful work occurring within our Boards across the state, common statewide drivers continue to evolve and the RPC -

B) Northeastern Regional Profiles

Oneida County HMP Draft 10/31/2013 1:08 PM Part III.B.3.2: Northeastern Regional Profiles b) Northeastern Regional Profiles The Northeastern Region identified for the Oneida County Hazard Mitigation Plan includes the following municipalities: The Town of Ava The Town and Village of Boonville The Town of Forestport The Town and Village of Remsen The Town of Steuben, and The Town of Western. Northeastern Regional Map A Page 1 of 33 Oneida County HMP Draft 10/31/2013 1:08 PM Part III.B.3.2: Northeastern Regional Profiles Regional Map B: 2013 Land Use in the Northeastern Region Page 2 of 33 Oneida County HMP Draft 10/31/2013 1:08 PM Part III.B.3.2: Northeastern Regional Profiles Regional Map C: New parcels since 2007. These communities tend to be dominated by rural landscapes and large wooded parcels. The region tends to be sparsely populated with an average population density of 36.5 persons per square mile with Ava at the low end of the spectrum at 17.95 and the Town of Boonville at the high end of the spectrum at 63.37. As a portion of the region is located within the Tughill Plateau, heavy rates of snowfall are not uncommon. While these communities tend to be well prepared for a snow storm that may cripple other areas, there is now also an awareness for the potential for severe damages from hurricanes, landslides and ice storms and severe storms. Flooding related to stormwater is an issue of concern in developed areas such as the Village of Remsen where widespread property damage has occurred on multiple occasions. -

The Roads Less Traveled: Minimum Maintenance Roads April 2017

ISSUE PAPER SERIES The Roads Less Traveled: Minimum Maintenance Roads April 2017 NEW YORK STATE TUG HILL COMMISSION DULLES STATE OFFICE BUILDING · 317 WASHINGTON STREET · WATERTOWN, NY 13601 · (315) 785-2380 · WWW.TUGHILL.ORG The Tug Hill Commission Technical and Issue Paper Series are designed to help local officials and citizens in the Tug Hill region and other rural parts of New York State. The Tech- nical Paper Series provides guidance on procedures based on questions frequently received by the Commis- sion. The Issue Paper Series pro- vides background on key issues facing the region without taking advocacy positions. Other papers in each se- ries are available from the Tug Hill Commission. Please call us or vis- it our website for more information. The Roads Less Traveled: Minimum Maintenance Roads Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1 What are minimum maintenance roads? .................................................................................................... 1 What is the legal status of minimum maintenance road designations? .................................................... 2 What does the proposed legislation do?..................................................................................................... 3 What does minimum maintenance mean? ................................................................................................. 3 What is the difference between -

Greater Syracuse Area Waterway Destinations and Services

Waterway Destinations and Services Map Central Square Y¹ `G Area Syracuse Greater 37 C Brewerton International a e m t ic Speedway Bradbury's R ou d R Boatel !/ y Remains of 5 Waterfront nt Bradbury Rd 1841 Lock !!¡ !l Fort Brewerton State Dock ou Caughdenoy Marina C !Z!x !5 Alb County Route 37 a Virginia St ert Palmer Ln bc !x !x !Z Weber Rd !´ zabeth St N River Dr !´ E R North St Eli !£ iver R C a !´ A bc d !º UG !x W Genesee St H Big Bay B D !£ E L ÆJ !´ \ N A ! 5 O C !l Marina !´ ! Y !5 K )§ !x !x !´ ÆJ Mercer x! Candy's Brewerton x! N B a Memorial 5 viga Ç7 Winter Harbor r Y b Landing le hC Boat Yard e ! Cha Park FA w nn e St NCH Charley's Boat Livery

Town of Sandy Creek Comprehensive Plan - September 2013 1 2 Town of Sandy Creek Comprehensive Plan - September 2013 Table of Contents

Town of Sandy Creek Comprehensive Plan - September 2013 1 2 Town of Sandy Creek Comprehensive Plan - September 2013 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction....................................................................7 Federal and State Land Use Policy............................................................9 Comprehensive Planning and Legislative Authority.............................11 Comprehensive Plan for the Town of Sandy Creek ..............................12 Chapter 2: Goals and Recommendations......................................15 Summary Analysis...............................................................................16 Community Vision Statement...........................................................18 Issues of Community Signifi cance.......................................................18 Strengths and Challenges..................................................................19 Community Goals and Recommended Actions.....................................29 Goal 1: Promote Good Governance.................................................30 Goal 2: Economic Development......................................................34 Goal 3: Environment and Natural Resources Protection.................36 Goal 4: Housing and Community Services ...................................39 Goal 5: Recreation and Cultural Development..............................41 Strategic Plan and Catalytic Projects................................................44 Plan Implementation..........................................................................44 -

Hartig Et Al. 2007. Indicator Project

Cover photos: Landsat 7 satellite image of western Lake Erie Basin and Detroit River corridor provided by USGS Landsat Project; Upper left: angler with walleye (Sander vitreus) by Jim Barta; Middle left: lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens) by Glenn Ogilvie; Lower left: Hexagenia by Lynda Corkum; Center: lake whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis) by James Boase/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; Lower right: juvenile peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus) by Craig Koppie/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; Bottom left: bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) by Steve Maslowski/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. STATE OF THE STRAIT STATUS AND TRENDS OF KEY INDICATORS Edited by: John H. Hartig, Michael A. Zarull, Jan J.H. Ciborowski, John E. Gannon, Emily Wilke, Greg Norwood, and Ashlee Vincent 2007 STATE OF THE STRAIT STATUS AND TRENDS OF KEY INDICATORS 2007 Edited by: John H. Hartig, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Michael A. Zarull, Environment Canada Jan J.H. Ciborowski, University of Windsor John E. Gannon, International Joint Commission Emily Wilke, Southwest Michigan Land Conservancy Greg Norwood, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Ashlee Vincent, University of Windsor Based on the Detroit River-Western Lake Erie Indicator Project, a three-year U.S.-Canada effort to compile and summarize long-term trend data, and the 2006 State of the Strait Conference held in Flat Rock, Michigan Suggested citation: Hartig, J.H., M.A. Zarull, J.J.H. Ciborowski, J.E. Gannon, E. Wilke, G. Norwood, and A. Vincent, eds. 2007. State of the Strait: Status and Trends of Key Indicators. Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research, Occasional Publication No.