DISASTERS and MISFORTUNES: the STORY of JOHN and JANE DANIELL by Martin Taylor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P1 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

P1 bus time schedule & line map P1 Frodsham - Priestley College View In Website Mode The P1 bus line (Frodsham - Priestley College) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Frodsham: 4:15 PM (2) Wilderspool: 7:46 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest P1 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next P1 bus arriving. Direction: Frodsham P1 bus Time Schedule 42 stops Frodsham Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 4:15 PM Greenalls Distillery, Wilderspool Tuesday 4:15 PM Loushers Lane, Wilderspool Wilderspool Causeway, Warrington Wednesday 3:30 PM Morrisons, Wilderspool Thursday 4:15 PM Friday 4:15 PM St Thomas' Church, Stockton Heath Saturday Not Operational Mullberry Tree Pub, Stockton Heath Methodist Church, Stockton Heath The Village Terrace, Warrington P1 bus Info Belvoir Road, Walton Direction: Frodsham Stops: 42 Walton Arms, Higher Walton Trip Duration: 54 min Line Summary: Greenalls Distillery, Wilderspool, Hobb Lane, Moore Loushers Lane, Wilderspool, Morrisons, Wilderspool, St Thomas' Church, Stockton Heath, Mullberry Tree Pub, Stockton Heath, Methodist Church, Stockton Ring O Bells, Daresbury Heath, Belvoir Road, Walton, Walton Arms, Higher Walton, Hobb Lane, Moore, Ring O Bells, Daresbury, D D Park Hotel, Daresbury Delph Park Hotel, Daresbury Delph, Chester Road, Preston on the Hill, Post O∆ce, Preston Brook, Chester Road, Chester Road, Preston on the Hill Preston Brook, Travel Inn, Preston Brook, Chester Road, Murdishaw, Post O∆ce, Sutton Weaver, Aston Post O∆ce, Preston -

A Glossary of Words Used in the Dialect of Cheshire

o^v- s^ COLONEL EGERTON LEIGH. A GLOSSARY OF WORDS USED IN THE DIALECT OF CHESHIRE FOUNDED ON A SIMILAR ATTEMPT BY ROGER WILBRAHAM, F.R.S. and F.S.A, Contributed to the Society of Antiquaries in iSiy. BY LIEUT.-COL. EGERTON LEIGH, M.P. II LONDON : HAMILTON, ADAMS, AND CO. CHESTER : MINSHULL AND HUGHES. 1877. LONDON : CLAY, SONS, AND TAYLOR, PRINTERS, » ,•*• EREA2) STH4iaT^JIIJ:-L,; • 'r^UKEN, V?eTO«IVS«"gBI?t- DEDICATION. I DEDICATE this GLOSSARY OF Cheshijie Words to my friends in Mid-Cheshire, and believe, with some pleasure, that these Dialectical Fragments of our old County may now have a chance of not vanishing entirely, amid changes which are rapidly sweeping away the past, and in many cases obliterating words for which there is no substitute, or which are often, with us, better expressed by a single word than elsewhere by a sentence. EGERTON LEIGH. M24873 PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS ATTACHED TO WILBRAHAM'S "CHESHIRE GLOSSARY." Although a Glossary of the Words peculiar to each County of England seems as reasonable an object of curiosity as its History, Antiquities, Climate, and various Productions, yet it has been generally omitted by those persons who have un- dertaken to write the Histories of our different Counties. Now each of these counties has words, if not exclusively peculiar to that county, yet certainly so to that part of the kingdom where it is situated, and some of those words are highly beautiful and of their and expressive ; many phrases, adages, proverbs are well worth recording, and have occupied the attention and engaged the pens of men distinguished for talents and learning, among whom the name of Ray will naturally occur to every Englishman at all conversant with his mother- tongue, his work on Proverbs and on the different Dialects of England being one of the most popular ones in our PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS. -

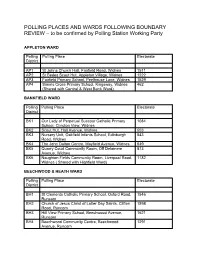

POLLING PLACES and WARDS FOLLOWING BOUNDARY REVIEW – to Be Confirmed by Polling Station Working Party

POLLING PLACES AND WARDS FOLLOWING BOUNDARY REVIEW – to be confirmed by Polling Station Working Party APPLETON WARD Polling Polling Place Electorate District AP1 St Johns Church Hall, Fairfield Road, Widnes 1511 AP2 St Bedes Scout Hut, Appleton Village, Widnes 1222 AP3 Fairfield Primary School, Peelhouse Lane, Widnes 1529 AP4 Simms Cross Primary School, Kingsway, Widnes 462 (Shared with Central & West Bank Ward) BANKFIELD WARD Polling Polling Place Electorate District BK1 Our Lady of Perpetual Succour Catholic Primary 1084 School, Clincton View, Widnes BK2 Scout Hut, Hall Avenue, Widnes 553 BK3 Nursery Unit, Oakfield Infants School, Edinburgh 843 Road, Widnes BK4 The John Dalton Centre, Mayfield Avenue, Widnes 649 BK5 Quarry Court Community Room, Off Delamere 873 Avenue, Widnes BK6 Naughton Fields Community Room, Liverpool Road, 1182 Widnes ( Shared with Highfield Ward) BEECHWOOD & HEATH WARD Polling Polling Place Electorate District BH1 St Clements Catholic Primary School, Oxford Road, 1546 Runcorn BH2 Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, Clifton 1598 Road, Runcorn BH3 Hill View Primary School, Beechwood Avenue, 1621 Runcorn BH4 Beechwood Community Centre, Beechwood 1291 Avenue, Runcorn BIRCHFIELD WARD Polling Polling Place Electorate District BF1 Halton Farnworth Hornets, ARLFC, Wilmere Lane, 1073 Widnes BF2 Marquee Upton Tavern, Upton Lane, Widnes 3291 BF3 Mobile Polling Station, Queensbury Way, Widnes – 1659 **To be re-sited further up Queensbury Way BRIDGEWATER WARD Polling Polling Place Electorate District BW1 Brook Chapel, -

CHRONICLES of THELWALL, CO. CHESTER, with NOTICES of the SUCCESSIVE LORDS of THAT MANOR, THEIR FAMILY DESCENT, &C

379 CHRONICLES OF THELWALL, CO. CHESTER, WITH NOTICES OF THE SUCCESSIVE LORDS OF THAT MANOR, THEIR FAMILY DESCENT, &c. &c. THELWALL is a township situate within the parochial chapelry of Daresbury, and parish of Runcorn, in the East Division of the hundred of Bucklew, and deanery of Frodsham, co. Chester. It is unquestionably a place of very great antiquity, and so meagre an account has been hitherto published a as to its early history and possessors, that an attempt more fully to elucidate the subject, and to concentrate, and thereby preserve, the scat• tered fragments which yet remain as to it, from the general wreck of time, cannot fail, it is anticipated, to prove both accept• able and interesting. The earliest mention that is to be met with of Thelwall appears in the Saxon Chronicle, from which we find that, in the year 923, King Edward the Elder, son of King Alfred, made it a garrison for his soldiers, and surrounded it with fortifications. By most writers it is stated to have been founded by this monarch, but the opinion prevails with some others that it was in existence long before, and was only restored by him. Towards the latter part of the year 923, King Edward is recorded to have visited this place himself, and for some time made it his residence, whilst other portion of his troops were engaged in repairing and manning Manchester. These warlike preparations, it may be observed, were rendered necessary in consequence of Ethelwald, the son of King Ethelbert, disputing the title of Edward. -

![11797 Mersey Gateway Regeneration Map Plus[Proof]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5912/11797-mersey-gateway-regeneration-map-plus-proof-245912.webp)

11797 Mersey Gateway Regeneration Map Plus[Proof]

IMPACT AREAS SUMMARY MERSEY GATEWAY 1 West Runcorn Employment Growth Area 6 Southern Widnes 8 Runcorn Old Town Centre plus Gorsey Point LCR Growth Sector Focus: Advanced Manufacturing LCR Growth Sector Focus: Advanced Manufacturing / LCR Growth Sector Focus: Visitor Economy / Financial & Widnes REGENERATION PLAN / Low Carbon Energy Financial & Professional Services Professional Services Waterfront New & Renewed Employment Land: 82 Hectares New & Renewed Employment Land: 12 Hectares New & Renewed Employment Land: 6.3 Hectares Link Key Sites: New Homes: 215 New Homes: 530 • 22 Ha Port Of Runcorn Expansion Land Key Sites: Key Sites: Everite Road Widnes Gorsey Point • 20 Ha Port Of Weston • 5 Ha Moor Lane Roadside Commercial Frontage • Runcorn Station Quarter, 4Ha Mixed Use Retail Employment Gyratory • 30 Ha+ INOVYN World Class Chemical & Energy • 3 Ha Moor Lane / Victoria Road Housing Opportunity Area & Commercial Development Renewal Area Remodelling Hub - Serviced Plots • 4 Ha Ditton Road East Employment Renewal Area • Runcorn Old Town Centre Retail, Leisure & Connectivity Opportunities: Connectivity Opportunities: Commercial Opportunities Widnes Golf Academy 5 • Weston Point Expressway Reconfiguration • Silver Jubilee Bridge Sustainable Transport • Old Town Catchment Residential Opportunities • Rail Freight Connectivity & Sidings Corridor (Victoria Road section) Connectivity Opportunities: 6 • Moor Lane Street Scene Enhancement • Runcorn Station Multi-Modal Passenger 3MG Phase 3 West Widnes Halton Lea Healthy New Town Transport Hub & Improved -

Draft Recommendations on the New Electoral Arrangements for Halton Borough Council

Draft recommendations on the new electoral arrangements for Halton Borough Council Electoral review December 2018 Translations and other formats: To get this report in another language or in a large-print or Braille version, please contact the Local Government Boundary Commission for England at: Tel: 0330 500 1525 Email: [email protected] Licensing: The mapping in this report is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. Licence Number: GD 100049926 2018 Contents Introduction 1 Who we are and what we do 1 What is an electoral review? 1 Why Halton? 2 Our proposals for Halton 2 How will the recommendations affect you? 2 Have your say 3 Review timetable 3 Analysis and draft recommendations 5 Submissions received 5 Electorate figures 5 Number of councillors 6 Ward boundaries consultation 7 Draft recommendations 8 Runcorn central 10 Runcorn east 12 Runcorn west 15 Widnes east 17 Widnes north 19 Widnes west 21 Conclusions 23 Summary of electoral arrangements 23 Have your say 25 Equalities 27 Appendices 28 Appendix A 28 Draft recommendations for Halton Borough Council 28 Appendix B 30 Outline map 30 Appendix C 31 Submissions received 31 Appendix D 32 Glossary and abbreviations 32 Introduction Who we are and what we do 1 The Local Government Boundary Commission for England (LGBCE) is an independent body set up by Parliament.1 We are not part of government or any political party. We are accountable to Parliament through a committee of MPs chaired by the Speaker of the House of Commons. -

Thelwall Archaeological Assessment 2003

CHESHIRE HISTORIC TOWNS SURVEY Thelwall Archaeological Assessment 2003 CHESHIRE HISTORIC TOWNS SURVEY Thelwall Archaeological Assessment 2003 Environmental Planning Cheshire County Council Backford Hall Backford Chester CH1 6PZ These reports are the copyright of Cheshire County Council and English Heritage. The Ordnance Survey mapping within this document is provided by Cheshire County Council under licence from the Ordnance Survey, in order to fulfil its public function to make available Council held public domain information. The mapping is intended to illustrate the spatial changes that have occurred during the historical development of Cheshire towns. Persons viewing this mapping should contact Ordnance Survey copyright for advice where they wish to licence Ordnance Survey mapping/map data for their own use. The OS web site can be found at www.ordsvy.gov.uk Front cover : John Speed’s Map of Lancashire 1610 Lancashire County Council http://www.lancashire.gov.uk/environment/oldmap/index.asp THELWALL ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT Mike Shaw & Jo Clark 1. SUMMARY Strictly speaking Thelwall does not qualify, and never has qualified, as a town. However, it is included in the survey of Cheshire’s Historic Towns because it was the site of a ‘burh’ ( a defended centre) in the early 10th century. Such sites were often created as, or grew into, trading centres and are therefore important examples of early urbanism in Cheshire. The burh is the focus of this assessment, therefore only brief attention is paid to the medieval and post medieval settlement. 1.1 Topography and Geology Thelwall lies in northern Cheshire at around 15m AOD, on the fringes of Warrington whose centre lies 4km to the west. -

Runcorn History Research 1. Primary Sources A

RUNCORN HISTORY RESEARCH 1. PRIMARY SOURCES A. Parliamentary A. 1 Acts and Orders of Parliament Inclosure Halton or Moor Moss Act 1816 Runcorn Improvement Act 1852 Runcorn Commissioners Act 1893 Local Government Board Provisional Orders (Confirmation No. 8)Act 1895 Cheshire Constabulary 1852 Runcorn, Weston & Halton Waterworks Act 1865 Runcorn, Weston & Halton Waterworks (Capital) Act 1870 Runcorn District Water Board Act 1923 Runcorn & District Water Board Act 1962 Runcorn Gas Act 1847 Runcorn Gas Act 1885 Runcorn & Weston Lighting (draft) Order 1910 Runcorn Urban & Runcorn Rural Electric Light Order 1910 Electric Lighting Orders (Confirmation No. 1) Act 1910 Widnes and Runcorn Bridge Act 1900 Widnes and Runcorn Bridge(Transfer) Act 1911 Ministry of Health Provisional Orders (No.8) 13.5.1921 Provisional Order for Altering Widnes and Runcorn Bridge Act 1900 and Widnes and Runcorn Bridge (Transfer) Act 1911. 1921 Tramways (Temporary Increase of Charges) Act 1920 Cheshire & Lancashire County Councils (Runcorn – Widnes Bridge) Act 1947 Runcorn - Widnes Bridge Act 1955 Chester and Warrington Turnpike Act 1786 Runcorn and Northwich Turnpike Act 1818 Weston Point Light Railway, Order 1920 Upper Mersey Navigation Act 1876 Weaver Navigation Act 1720 Weaver Navigation Act 1760 Weaver Navigation Act 1807 Weaver Navigation Act 1840 Weaver Navigation Act 1866 Weaver Navigation Act 1928 Bridgewater Trust (ref. Weston Canal) Act 1857 The Bridgewater Canal (Waterloo Bridge) (Local Enactments) Order 1973 Manchester Ship Canal Act 1885 Manchester Ship -

Ton//Wa4 4Hs to Let Location / Description / Accommodation / Terms / Contact

HIGH QUALITY MODERN SELF-CONTAINED OFFICE BUILDING 31,250 SQ FT (2,903 SQ M) DARESBURY PARK DARESBURY//WARRINGTON//WA4 4HS TO LET LOCATION / DESCRIPTION / ACCOMMODATION / TERMS / CONTACT Daresbury Park has developed as one of the region's most attractive office locations, sitting right at J11 of the M56, ensuring superb access to Manchester International and John Lennon Airports, the regional motorway network and a high quality labour force. Warrington lies some 5 miles to the north, whilst Manchester can be reached within 30 minutes. Extending to 225 acres (91 ha) approx, the development has attracted technology companies such as Vistorm and Appsense, as well as Virgin Care, BNFL & ABB. Daresbury Park Hotel provides an on site leisure club and conference venue, whilst further development at Daresbury Park will include retail and leisure facilities, along with a creche. CLICK FOR MAPS CLICK FOR AERIAL HIGH QUALITY MODERN SELF-CONTAINED OFFICE BUILDING DARESBURY PARK 31,250 SQ FT (2,903 SQ M) TO LET DARESBURY//WARRINGTON//WA4 4HS L L I M LOCATION DESCRIPTION ACCOMMODATION TERMS CONTACT / / / / MANCHESTER SHIP CANAL 32 A56 M65 3 1 M55 4 A583 A59 8 BURNLEY LYTHAM 7 31 6 ST ANNES ACCRINGTON PRESTON BLACKBURN 30 OSWALDTWISTLE A646 MANCHESTER SHIP CANAL 6 5 5 9/2 3 4 A BACUP LEYLAND 28 D A56 A558 D R DARWEN A6033 A R A565 8 AY RE E M6 W S T SOUTHPORT CHORLEY S B A666 ES U S 1 R R E ROCHDALE P A59 X Y BRIDGEWATER CANAL E E H M61 BOLTON RY C A570 BURY 21 BU XP A5209 2 ES R A565 27 A58 20 R ESS 19 A D 6 D W RADCLIFFE A627(M) E A WIGAN L Y 5 4/18 -

Daresbury Court Evenwood Close Manor Park, R Uncorn WA7 1LZ

MULTI-LET OFFICE PARK INVESTMENT Daresbury Court evenwooD Close Manor Park, r unCorn WA7 1lZ CliCk here to view vi Deo MULTI-LET OFFICE PARK INVESTMENT DARESBURY COURT, EVENWOOD CLOSE, MANOR PARK, RUNCORN, WA7 1LZ 2 investMent summary •• Multi-let•modern•office•park•set•within•a•pleasant•landscaped• •• The•property•currently•produces•£199,127•per•annum•which• environment• equates•to•just•£13.50•psf •• Highly•accessible•location•with•excellent•motorway•and•main• •• Average•weighted•un-expired•term•of•3.14•years•to•expiry•and• road•connectivity•• 1.1•years•to•earliest•determination •• Connectivity•is•to•be•significantly•improved•with•the• •• Opportunity•to•improve•the•existing•income•profile•through• completion•of•The•Mersey•Gateway,•scheduled•for•autumn•2017• lease•re-gears,•removal•of•break•options•and•re-letting•of• improving•accessibility•and•reducing•drive•times•to•the•M62,• vacant•accommodation•within•12•month•guarantee•period Speke•and•Liverpool •• Our•client•is•seeking•offers•in•excess•of•£1,825,000•(subject•to• •• 4-unit•business•park•extending•to•14,752•sq•ft•(2•further•units• contract) sold•off•LLH•for•999•years•at•a•peppercorn) •• A•purchase•at•this•level•reflects•a•Net•Initial•Yield•of•10.27%• •• 100•car•parking•spaces •• Extremely•low•capital•value•of•just•£124 psf •• Freehold A59 A580 23 MULTI-LET OFFICE PARK INVESTMENT DARESBURY COURT, EVENWOOD MANCHESTERCLOSE, MANOR PARK, RUNCORN, WA7 1LZ 3 ST HELENS A58 A5058 M60 A57 10/21A 1 A57 2 M62 A56 9 loCation 1/6 WARRINGTON 21 BIRKENHEAD HOYLAKE Daresbury•is•situated•in•the•North•West•of•England•in•the•county•of•Cheshire,•approximately•9•miles• -

Find out More on Junction 11 M56, Cheshire from 8,000 to 500,000 Sqft

J11 M56 Design & build opportunities from 8,000 to 500,000 sqft Find out more on Junction 11 M56, Cheshire Intro Masterplan Design & build Location Connectivity Amenities Occupiers Gallery Contact Why Daresbury Park? Daresbury Park is a key strategic site for business development and growth with over 5 million people living within 5 million people a 45 minute drive time of the park. within 45 mins Comprising 225 acres (91 hectares) with planning consent for approximately 1.6 million square feet, the park provides an exceptional environment which is already home to numerous international businesses. Daresbury Park benefits from direct access onto the M56 motorway at junction 11 and is equidistant between Planning for Manchester and Liverpool airports (15 miles). 1.6 million sqft The M6 and M62 motorways are both within a 10 minute drive. The park has excellent on-site amenities with Daresbury Park Hotel offering extensive conference facilities, coffee shop, restaurants and leisure facilities including a gymnasium, spa and swimming pool. Manchester & Liverpool airports 20 mins Daresbury Park is owned by Marshall CDP, an established local developer with 100 years of experience, who have delivered over 2 million square feet of commercial space in the last 5 years alone. M6 & M62 motorways 10 mins Intro Masterplan Design & build Location Connectivity Amenities Occupiers Gallery Contact Masterplan Site 3 Site 1 Masterplan Site 1 Site 2 Site 3 Daresbury Park can cater for building sizes ranging from 8,000 to 500,000 sqft and a number of options can be presented on the site to suit an organisation’s preference. -

Cheshire Ancestor Registered Charity: 515168 Society Website

Cheshire AnCestor Registered Charity: 515168 Society website: www.fhsc.org.uk Contents Editorial 2 How to Find New Relatives and get Chairman’s Jottings 3 Hooked on Genealogy in a Year 31 Mobberley Research Centre 5 Spotlight on Parish Chest Membership Issues 10 Settlements and Removals 36 Family History Events 11 Stockport BMDs 38 Family History News 15 DNA and the Grandmother Family History Website News 16 Conundrum 40 Books Worth Reading 19 Certificate Exchange 43 Letters to the Editor 22 Net That Serf (grey pages) 46 Help Wanted or Offered 25 Group Events and Activities 56 Aspects of a Registrar’s Professional New Members (green pages) 66 Life 27 Members’ Interests 71 Cover picture: Over (Winsford), St. Chad. The church is late fifteenth century with a tower added in the early sixteenth century. The chancel was lengthened in 1926. There is a monument to Hugh Starkey who rebuilt the church in 1543. Cheshire AnCestor is published in March, June, September and December (see last page). The opinions expressed in this journal are those of individual authors and do not necessarily represent the views of either the editor or the Society. All advertisements are commercial and not indicative of any endorsement by the Society. No part of this journal may be reproduced in any form whatsoever without the prior written permission of the editor and, where applicable, named authors. The Society accepts no responsibility for any loss suffered directly or indirectly by any reader or purchaser as a result of any advertisement or notice published in this Journal. Please send items for possible publication to the editor: by post or email.