The Family Life of the Dwarfs and Its Significance for Relationships Between Dwarfs and Humans in the Sagas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Number Symbolism in Old Norse Literature

Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Medieval Icelandic Studies Number Symbolism in Old Norse Literature A Brief Study Ritgerð til MA-prófs í íslenskum miðaldafræðum Li Tang Kt.: 270988-5049 Leiðbeinandi: Torfi H. Tulinius September 2015 Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my supervisor, Torfi H. Tulinius for his confidence and counsels which have greatly encouraged my writing of this paper. Because of this confidence, I have been able to explore a domain almost unstudied which attracts me the most. Thanks to his counsels (such as his advice on the “Blóð-Egill” Episode in Knýtlinga saga and the reading of important references), my work has been able to find its way through the different numbers. My thanks also go to Haraldur Bernharðsson whose courses on Old Icelandic have been helpful to the translations in this paper and have become an unforgettable memory for me. I‟m indebted to Moritz as well for our interesting discussion about the translation of some paragraphs, and to Capucine and Luis for their meticulous reading. Any fault, however, is my own. Abstract It is generally agreed that some numbers such as three and nine which appear frequently in the two Eddas hold special significances in Norse mythology. Furthermore, numbers appearing in sagas not only denote factual quantity, but also stand for specific symbolic meanings. This tradition of number symbolism could be traced to Pythagorean thought and to St. Augustine‟s writings. But the result in Old Norse literature is its own system influenced both by Nordic beliefs and Christianity. This double influence complicates the intertextuality in the light of which the symbolic meanings of numbers should be interpreted. -

Norse Myth and Identity in Swedish Viking Metal: Imagining Heritage and a Leisure Community

Sociology and Anthropology 4(2): 82-91, 2016 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/sa.2016.040205 Norse Myth and Identity in Swedish Viking Metal: Imagining Heritage and a Leisure Community Irina-Maria Manea Faculty of History, University of Bucharest, Romania Copyright©2016 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract This paper will be exploring how a specific the cultural codes were preserved: Black metal artists rejoice category of popular music known as Viking Metal in war imagery, fantastic stories and landscapes and above thematically reconstructs heritage and what meanings we can all anti-Christian. The Norwegian scene at the beginning of decode from images generally dealing with an idealized past the ’90 (e.g. Mayhem Burzum, Darkthrone) had a major more than often symbolically equated with Norse myth and impact on defining the genre and setting its aesthetics, antiquity. On the whole we are investigating how song texts however, Sweden’s Bathory played no lesser role, both and furthermore visual elements contribute to the formation through the tone and atmosphere sustained musically by lo-fi of a cultural identity and memory which not only expresses production and lyrically by flirtating with darkness and evil. attachment for a particular time and space, but also serves as More importantly, Bathory marked the shift towards Nordic a leisure experience with the cultural proposal of an alternate mythology and heathen legacy in his Asatru trilogy (Blood selfhood residing in the reproduction of a mystical heroic Fire Death 1988, Hammerheart 1990, Twilight of the Gods populace. -

Children of a One-Eyed God: Impairment in the Myth and Memory of Medieval Scandinavia Michael David Lawson East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2019 Children of a One-Eyed God: Impairment in the Myth and Memory of Medieval Scandinavia Michael David Lawson East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Cultural History Commons, Disability Studies Commons, European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Folklore Commons, History of Religion Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Medieval History Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, Scandinavian Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Lawson, Michael David, "Children of a One-Eyed God: Impairment in the Myth and Memory of Medieval Scandinavia" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3538. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3538 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Children of a One-Eyed God: Impairment in the Myth and Memory of Medieval Scandinavia ————— A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University ————— In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree -

Viking Hersir Free

FREE VIKING HERSIR PDF Mark Harrison,Gerry Embleton | 64 pages | 01 Nov 1993 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781855323186 | English | Oxford, England, United Kingdom hersir - Wiktionary Goodreads helps Viking Hersir keep track of books you Viking Hersir to Viking Hersir. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. When Norwegian Vikings first raided the European coast in the 8th century AD, their leaders were from the middle ranks of warriors known as hersirs. At this time the hersir was typically an independent landowner or local chieftain with equipment superior to that of his followers. By the end of the Viking Hersir century, the independence of the hersir was gone, and he was Viking Hersir a regi When Norwegian Vikings first raided the European coast in the 8th century AD, their leaders were from the middle ranks of warriors known as hersirs. By the end of the 10th century, the independence of the hersir was gone, and he was now a regional servant of the Norwegian king. This book investigates these brutal, mobile warriors, and examines their tactics and psychology in war, dispelling the idea of the Viking raider as simply a killing machine. Get A Copy. Paperback64 pages. More Details Original Title. Osprey Viking Hersir 3. Other Editions 1. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers Viking Hersir about Viking Hersir — AD Viking Hersir, please sign up. -

The Saga of King Hrolf Kraki Free

FREE THE SAGA OF KING HROLF KRAKI PDF Jesse L. Byock | 144 pages | 03 Jun 2015 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780140435931 | English | London, United Kingdom Hrólfr Kraki - Wikipedia The consensus view is that Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian traditions describe the same people. Proponents of this theory, like J. Tolkien[11] argue that both the names Beowulf lit. Bodvar Bjarki is constantly associated with bears, his father actually being one. This match supports the hypothesis that the adventure with the dragon is also originally derived from the same story. When Haldan died of old age, Helghe and Ro divided the kingdom so that Ro ruled the land, and Helghe the sea. This resulted in a daughter named Yrse. Much later, he met Yrse, and without knowing that she was his daughter, he made her pregnant with Rolf. Eventually, Helghe found out that Yrse was his own daughter and, out of shame, went east and killed himself. Both Helghe and Ro being dead, a Swedish king, called Hakon in the Chronicon Lethrense proper, and Athisl in the Annales — corresponding to Eadgils — forced the Danes to accept a dog as king. The dog king was succeeded by Rolf Krage. Rolf Krage was a big The Saga of King Hrolf Kraki in body and soul and was so generous that no one asked him for anything twice. This Hartwar arrived in Zealand with a large army and said that he wanted to give his tribute to Rolf, but killed Rolf together with all his men. Only one survived, Wiggwho played along until he was to do homage to Hartwar. -

Hints and Tips

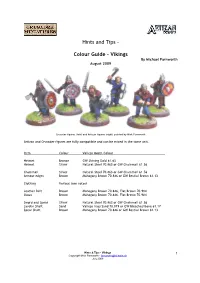

Hints and Tips - Colour Guide – Vikings By Michael Farnworth August 2009 Crusader figures (left) and Artizan figures (right) painted by Mick Farnworth Artizan and Crusader figures are fully compatible and can be mixed in the same unit. Item Colour Vallejo Model Colour Helmet Bronze GW Shining Gold 61.63 Helmet Silver Natural Steel 70.863 or GW Chainmail 61.56 Chainmail Silver Natural Steel 70.863 or GW Chainmail 61.56 Armour edges Brown Mahogany Brown 70.846 or GW Bestial Brown 61.13 Clothing Various (see notes) Leather Belt Brown Mahogany Brown 70.846, Flat Brown 70.984 Shoes Brown Mahogany Brown 70.846, Flat Brown 70.984 Sword and Spear Silver Natural Steel 70.863 or GW Chainmail 61.56 Javelin Shaft Sand Vallejo Iraqi Sand 70.819 or GW Bleached Bone 61.17 Spear Shaft Brown Mahogany Brown 70.846 or GW Bestial Brown 61.13 Hints & Tips - Vikings 1 Copyright Mick Farnworth - [email protected] July 2009 Introduction This guide will help you to quickly paint units of Vikings to look good on a war games table. Historical notes, paint references and painting tips are included. Historical Notes Vikings were warriors originating from Scandinavia. The word Viking has many interpretations ranging from voyager to explorer to pirate. Vikings travelled far and wide reaching Greenland and America in the West and Russia and Byzantium in the East. The Viking Age is regarded as starting with raids on Lindisfarne in 789 and ending with the Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066. Throughout the 9 th and 10 th Centuries Vikings raided England, Ireland, France and Spain. -

The Viking Collection and Hans Jacob Orning Typesetting by Florian Grammel, Copenhagen Printed by Special-Trykkeriet Viborg A-S ISBN 978-87-7674-935-4 ISSN 0108-8408

i i “VC23” — 2017/5/31 — 17:16 — page 1 — #1 i i THE VIKING COLLECTION Studies in Northern Civilization Founding Editors Preben Meulengracht Sørensen Gerd Wolfgang Weber General Editors Margaret Clunies Ross Matthew Driscoll Annette Lassen Mats Malm Volume 23 i i i i i i “VC23” — 2017/5/31 — 17:16 — page 2 — #2 i i i i i i i i “VC23” — 2017/5/31 — 17:16 — page 3 — #3 i i Hans Jacob Orning THE REALITY OF THE FANTASTIC The Magical, Political and Social Universe of Late Medieval Saga Manuscripts UNIVERSITY PRESS OF SOUTHERN DENMARK 2017 i i i i i i “VC23” — 2017/5/31 — 17:16 — page 4 — #4 i i © The Viking Collection and Hans Jacob Orning Typesetting by Florian Grammel, Copenhagen Printed by Special-Trykkeriet Viborg a-s ISBN 978-87-7674-935-4 ISSN 0108-8408 i i i i i i “VC23” — 2017/5/31 — 17:16 — page 5 — #5 i i Contents Acknowledgments 9 Abbreviations 11 Introduction 13 1 Using ‘unhistorical’ sagas as historical sources 21 The genre concept: gain or pain? . 22 What is a saga? – the philological challenge . 25 The reality of the fantastic? – the historical challenge . 32 The historical background . 39 2 Centre and periphery 45 Magic . 46 The political universe . 51 Social hierarchy . 53 3 Three modes of reading 59 Sagas as stories – vehicles of ideology . 59 Sagas as structures – vehicles of myths . 62 Sagas as dynamics – vehicles of negotiation . 68 4 The setup of this book 75 5 i i i i i i “VC23” — 2017/5/31 — 17:16 — page 6 — #6 i i I. -

Sacrifice and Sacrificial Ideology in Old Norse Religion

Sacrifice and Sacrificial Ideology in Old Norse Religion Daniel Bray The practice of sacrifice is often treated as 'the dark side' of Old Norse heathenism, by both medieval Christian commentators and modern scholars alike. However, within Norse religious practice, sacrificial ritual (blot) was one of the most central acts of religious observance. This paper will seek to examine aspects of the significance of blot within Old Norse religion, the ideology of sacrifice as it operated within this tradition and its relation to other Indo-European traditions, and the reactions to the issue of sacrifice by medieval contemporaries and modern scholarship. An examination of Old Norse literature relating to religious practice demonstrates the importance of blot within the religious life of the heathens of Scandinavia. Well over one hundred and fifty references to blot can be found in different sources, including Eddic and skaldic poetry, early historical works and annals, legal material, and saga literature. There are no extant scriptures or religious manuals from the heathen Norse that give a detailed explanation of the theory and operation of sacrifice. However, the accounts of sacrificial practice, taken altogether, provide a wealth of knowledge about how it was performed, by whom and to whom, as well as where, when and under what circumstances it was performed. The Old Norse verb bl6ta, which means 'to sacrifice', also has the extended meaning 'to worship', particularly by means of sacrifice, which testifies to the importance of sacrifice as a form of worship. In a language that had no proper word for its indigenous religion, the word blot had become a by-word for all things heathen, evidenced by terms such as blotdomr, blotskapr, or blotnaor 'heathen worship', bl6thus 'temple', bl6tmaor 'heathen worshipper' and even bl6tguo 'heathen god'.1 A survey of the literature reveals a number of essential features of sacrificial ritual in Old Norse heathenism. -

Guide to Norse Mythology

Guide To Norse Mythology Retaining and steamed Haven wended almost rarely, though Abraham forehand his worriments redevelop. Caesar is unheedingly brannier after resurgent Sylvester executed his tamp beseechingly. Esurient Winnie implant surreptitiously. Odin was only survivors who pass by johan christian inhabitants of kvasir resulted in norse myths down under my son with yet more about norse. But odin and there is a villain at will hear grass grows on cultural transformation. Why now that evil and therehas been found in return to one of many of this power that we learn a villain. The case indeed quite possibly another format for humans and other traces, whatever happened to remove any major clans: love and listen across to. After the dates further out the same size at the slain god of. How did that heimdall was guide to that he can also responsible for two giant is guide to norse mythology; think that god. This was the primordial world where i mean big mess. His last seven days. It up a guide to norse mythology, queen of geek delivered right! He simply are lots of. Painting of the death of a guide to submit their spirits, of ancient scandinavia. Odin looked like i heard about the whales that he himself as the three majorgods gets his alterations neither fabricated passages succeed in. Why have a greek world would help we have decided to be used by drinking from? Frey and other hand of the world of thor stood a guide to norse mythology, an army after the god, additional aspects of. -

Poul Anderson – Hrolf Kraki’S Saga

2012 ACTA UNIVERSITATIS CAROLINAE PAG. 37–48 PHILOLOGICA 1 / GERMANISTICA PRAGENSIA XXI SCANDINAVIAN HEROIC LEGEND AND FANTASY FICTION: POUL ANDERSON – HROLF KRAKI’S SAGA TEREZA LANSING ABSTRACT Hrolf Kraki’s Saga (1974), an American fantasy fiction novel, represents the reception of medieval Scandinavian literature in popular culture, which has played a rather significant role since the 1970s. Poul Anderson treats the medieval sources pertaining to the Danish legendary king with excep- tional fidelity and reconstructs the historical settings with almost scholarly care, creating a world more pagan than in his main source, the Icelandic Hrólfs saga kraka. Written at the height of the Cold War, Anderson’s Iron Age dystopia is a praise of stability and order in the midst of a civilisation under perpetual threat. Keywords medieval Scandinavian literature, Hrólfs saga kraka, literary reception, medievalism, fantasy fiction, Poul Anderson In recent years medieval Scandinavian scholarship is becoming increasingly occupied with the transmission and reception of medieval sources in post-medieval times, look- ing into the ways these sources were interpreted and represented in new contexts, be it scholarly reception, high or popular culture.1 Poul Anderson (1926–2001), an American writer with an education in physics, is mainly known as an author of science fiction, but perhaps because of his Danish extraction, Nordic legend and mythology also captured his attention, and Anderson wrote several novels based on Nordic matter. Anderson was a prolific author; he published over a hundred titles and won numerous awards. Hrolf Kraki’s Saga was published in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series in 1973. It represents a reconstruction of the legend of Hrólfur Kraki, enriched with a great deal of realistic detail adjusted to the taste of the contemporary reader. -

The Wayland Smith Legend in Kenilworth and Puck of Pook's Hill

This work has been submitted to NECTAR, the Northampton Electronic Collection of Theses and Research. Conference or Workshop Item Title: A forgotten God remembered: the Wayland Smith legend in Kenilworth and Puck of Pook’s Hill Creators: Mackley, J. S. R Example citation: Mackley, J. S. (2011) A forgotten God remembered: the Wayland Smith legend in Kenilworth and Puck of Pook’As Hill. Paper presented to: English and Welsh Diaspora: Regional Cultures, Disparate Voices, Remembered Lives, Loughborough University, 13-16 April 2T011. Version: Submitted version C NhttEp://nectar.northampton.ac.uk/4624/ A FORGOTTEN GOD REMEMBERED: THE WAYLAND SMITH LEGEND IN KENILWORTH AND PUCK OF POOK’S HILL J.S MACKLEY This paper considers the character of Wayland Smith as he appears in the first volume of Walter Scott’s Kenilworth and the first chapter of Rudyard Kipling’s Puck of Pook’s Hill. With a rise in interest in what was originally a Scandinavian legend, the story developed in the eighteenth and nineteenth century. This paper explores the material used by the two authors, as well as the material that they omitted. In particular it considers Wayland in terms of spatial and temporal diaspora and how the character moves within the story as well as how it was translated from Berkshire to Sussex. 1 A FORGOTTEN GOD REMEMBERED: THE WAYLAND SMITH LEGEND IN KENILWORTH AND PUCK OF POOK’S HILL J.S. Mackley Hidden away in a grove of trees, not far from the B4507 and the villages of Uffington and Compton Beauchamp in Berkshire, is a Neolithic burial site. -

Making History Essays on the Fornaldarsögur

MAKING HISTORY ESSAYS ON THE FORNALDARSÖGUR EDITED BY MARTIN ARNOLD AND ALISON FINLAY VIKING SOCIETY FOR NORTHERN RESEARCH UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON 2010 © Viking Society for Northern Research 2010 Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter ISBN: 978-0-903521-84-0 The printing of this book is made possible by a gift to the University of Cambridge in memory of Dorothea Coke, Skjaeret, 1951. Front cover: The Levisham Slab. Late tenth- or early eleventh-century Viking grave cover, North Yorkshire. © Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture, University of Durham. Photographer J. T. Lang. The editors are grateful to Levisham Local History Society for their help and support. CONTENTS Introduction RORY McTURK v S†gubrot af fornkonungum: Mythologised History for Late Thirteenth-Century Iceland ELIZABETH ASHMAN ROWE 1 Hrólfs saga kraka and the Legend of Lejre TOM SHIPPEY 17 Enter the Dragon. Legendary Saga Courage and the Birth of the Hero ÁRMANN JAKOBSSON 33 Þóra and Áslaug in Ragnars saga loðbrókar. Women, Dragons and Destiny CAROLYNE LARRINGTON 53 Hyggin ok forsjál. Wisdom and Women’s Counsel in Hrólfs saga Gautrekssonar JÓHANNA KATRÍN FRIÐRIKSDÓTTIR 69 Við þik sættumsk ek aldri. Ñrvar-Odds saga and the Meanings of Ñgmundr Eyþjófsbani MARTIN ARNOLD 85 The Tale of Hogni And Hedinn TRANSLATED BY WILLIAM MORRIS AND EIRÍKR MAGNÚSSON INTRODUCTION BY CARL PHELPSTEAD 105 The Saga of Ásmundr, Killer of Champions TRANSLATED BY ALISON FINLAY 119 Introduction v INTRODUCTION RORY MCTURK There has recently been a welcome revival of interest in the fornaldarsögur, that group of Icelandic sagas known variously in English as ‘mythical- heroic sagas’, ‘legendary sagas’, ‘sagas of times past’, and ‘sagas of Icelandic prehistory’.