Scottish Proverbs, Collected and Arranged

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2004 Crosscut Literary Magazine

Cover Photo: “Rocks” by Kathy Wall wrapped from the front to the back cover. Crosscut literary magazine Husson College Bangor, Maine 2004 Volume Twelve i Crosscut EDITORIAL STAFF Editors Greg Winston Amanda Kitchen Cover Photo “Rocks” Kathy Wall Crosscut website: http://english.husson.edu/crosscut/ First Edition. Press run of 500 copies; no reprinting is planned. Printed by Fast Forms Printing & Paper, Bangor, Maine. Funded by Husson College. All rights to individual works are retained by their authors. For permission to reprint, contact the authors and artists directly. Address all correspondence and submissions (up to three poems, three drawings or photographs, or prose selections up to 5,000 words) to Editorial Staff, Crosscut magazine, Department of English, Husson College, One College Circle, Bangor, ME 04401. ii Preface The mere thought of spring brings to mind together- ness and renewal. Rivers of melting snow and ice form tributaries, finding each other and crossing paths, flow- ing together to free themselves from their stagnant form. The once-frozen paths weaving throughout our Maine woods shed their white armor, heartedly inviting pairs of treaded footprints to meet along their crossing journeys. Gloves and mittens are tossed in the closet for another year, allowing loved ones to entwine their hands into one another’s as they venture out into the fresh new season. Over the years, Crosscut has become a powerful symbol of spring in just this light. The poetry, prose, and imagery in each of its contributor’s art flows together, melting movement and life into the freshly printed pages. Its readers, in turn, breathe in each stir of emotion and new image formed, feeling renewed and refreshed. -

Horse Races at Lowell Saturday, August 5

i «y«™oi, Puuic tiIinii.v THE LOWELL LEDGER VOL. XIX LOWELL, MICHIGAN, AUG 3, IC>II No. 7 JPAY YOUR BILLS GONETOHiSnRDAOII PIONEER PICNIC AIIENIN PLEASE Are you Particular Charles Taylor, Old Resident, Famous Annual Event Booked Twenty-fivfi Rural Letters in ^ With Checks and you will never have to pay the seen dtime 4 . * Rests After Long Illness. for Thursday, Aug. 17. This Issue Alter an illm'ss of several The pioneers and their descen- The at tentiou of rural readers Every check you give has to be endorsed by he Enough About Drugs J. months, our olillik'iulainl IUMUII- dants of Ada, and snrronndiny; is called lo the splendid array of 4- person receiving it before he can get the mo. ey bor, riiarlcs Taylor, passcil from towns in the (Jrand lliver Valley rural letters being published in 1 and when the checks are returned to you you have his lioim la this villa,uv to his will hold t heir annual basket T L IIK KHCIOU: Look over Hiis Do you make sure of right quality, or do you do as I lite hest kind of a receipt and one that cannot be etonuil reward. Suaday at about picnic at SelKMick's <j,rove, Ada issue—I wenly-tive ol I hem. ho disputed. Your money is always safe when de- niHl- lay, at thu niic old aiiv of village, Thursday. Anii-. 17. Kx- you realize that means a whole thousands of others do just call for an article and take posited in the bank and is as convenient to use as •SO yea i s. -

Deads Mans Plack and Old Thorn

THIS EDITION IS LIMITED TO 75O COPIES FOR SALE IN ENGLAND, IOO FOR SALE IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, AND 35 PRESENTATION COPIES THE COLLECTED WORKS °f W. H. HUDSON IN TWENTY-FOUR VOLUMES ADVENTURES AMONG BIRDS ADVENTURES AMONG BIRDS BY W. H. HUDSON MCMXXIII LONDON y TORONTO J. M. DENT & SONS LTD. NEW YORK: E. P. DUTTON & CO. A ll rights reserved PRINTBD IN CRKAT BRITAIN A considerable portion of the matter contained herein has appeared in the English Review, Cornhill Magazine, Saturday Review, Nation, and a part of one chapter in the Morning Post. These articles have been altered and extended, and I am obliged to the Editors and Publishers for permission to use them in this book. Once I was part of the music I heard On the boughs or sweet between earth and sky, For joy of the beating of wings on high My heart shot into the breast of a bird. I hear it now and I see it fly. And a Ufe in wrinkles again is stirred, My heart shoots into the breast of a bird, As it will for sheer lo ve till the last long sigh. Meredith. CONTENTS CHAPTER I PAGE The Book: An Apology ...... i A preliminary warning—Many books about a few birds— People who discover well-known birds—An excuse for the multiplicity of bird-books—Universal delight in wild birds—Interview with a county councillor—A gold-crest’s visit to a hospital—A rascal’s blessing— Incident of the dying Garibaldi and a bird. CHAPTER II Cardinal: The Story of my First Caged Bird. -

Dempsey Reveals Program To

I The Weather Average D aily N et PM aa Rim Fereeaet of V. S. Woemer MtNl For tae Week IM M Jtmamrr M, liflS Clear, very eelfi taalgM, Iwr • to 5 belowt eoMay, eoatfaMM eel 14,145 iKinierpew, Mgh Bear M. Member of the Audit Bureau tit CtrcuIatloB ManeheHer—‘A City of Village Charm (Ofauelfied Advertifihig oa Page Ifl) PRICE SEVEN CRNm MANCHESTER, CONN., TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 2, 1965 (EIGHTEEN PAGES) VOL. LXXXIV, NO. 104 Dempsey Reveals Program To ‘Keep Connecticut Best’ of Greater Aid Events To Education In State Among Aims Water Gompanies HARTFORD (AP) — Gov. John N. Dempsey Seeking to Own recommended to the 1965 General Assembly today a Pipe Connection program calling for great- er state aid to education, HARTFORD (AP) — expanded mental health Connecticut water com- and mental retardation fa- panies have asked the state cilities, and tighter civil to modify rules that would rights laws. have them own the service In a speech marking the open- connection from the main ing of what will be tte regular ' in the street to the custom- biennial session for 1966, the er’s property. Democratic governor also called A brief filed with the State for more housing for the elderly, Public UUllties Commission by 1 aid to the bankrupt New Haven attorneys for the Connecticut 1 Railroad, and expanded urban renewal, open spaces, and wa- Waterworks Association ask.*’ Flames soar high in the air as firemen battle a million dollar fire, that swept that Customers pay "excavation , ter and air pollution programs. I For the first time in a formal through a hve-atory building in downtown Meriden. -

New Mexico Baptist Foundation and Church Finance Corporation Presented Their Report

Annual The Baptist Convention of New Mexico 2005 Convention of Mexico New Baptist The Annual Albuquerque, NM 87199 NM Albuquerque, 94485 Box PO NM of Convention Baptist The - 4485 2005Annual The Baptist Convention of New Mexico Permit #1603 Albuquerque, NM PostagePaid US Non Acting Executive Director - Profit Org. Dr. James Semple Nancy L. Faucett, Recording Secretary (505) 924-2300; FAX (505) 924-2349 www.bcnm.com ANNUAL of The Baptist Convention of New Mexico PO Box 94485, Albuquerque 87199 5325 Wyoming NE, Albuquerque 87109 Ninety-Fourth Annual Session Meeting at First Baptist Church Bloomfield, New Mexico October 25-26, 2005 OFFICERS OF THE CONVENTION President Jay McCollum, Gallup First Vice President Randy Aly, Jal Recording Secretary Nancy Faucett, Edgewood Assistant Recording Secretary Cricket Pairett, Albuquerque Parliamentarian Francis Wilson, Albuquerque 2006 Meeting to be held October 24-25 at Central Baptist Church of Clovis, New Mexico Shon Wagner, T or C First Preacher of Annual Sermon Billy Weckel, Deming First Alternate 2007 Meeting October 23-24 Albuquerque Sandia 2008 Meeting October 28-29 Las Cruces First DEDICATION The 2005 Annual for the Baptist Convention of New Mexi- co is dedicated to Dr. James H. Semple, who served as the state convention’s acting executive director from March 1, 2005, to Feb. 1, 2006. During the time he was leading New Mexico Baptists, he also served as the BCNM’s interim director of evangelism ministries, a post he had held since May of 2004. He com- muted to New Mexico each week from his home in Dallas. Semple retired in 2001 after serving 12 years as director of the State Missions Commission of the Baptist General Convention of Texas. -

Wed, 13 Aug 1997 12:33:00 +0200 (MET DST) From: Anders Thulin

Date sent: Wed, 13 Aug 1997 12:33:00 +0200 (MET DST) From: Anders Thulin <[email protected]> Send reply to: Anders Thulin <[email protected]> Subject: Waverley To: [email protected] Sir Walter Scott: Waverley ========================== a machine-readable transcription Version 1.1: 1997-07-16 For information about the source edition and the transcription markup used, please see the notes at the end of this file ----------------------------------------------------------------------- <title page> WAVERLEY OR 'TIS SIXTY YEARS HENCE By SIR WALTER SCOTT, Bart. Under which King, Bezonian? speak, or die! _Henry IV. Part II._ <dedication> TO MARY MONICA HOPE SCOTT OF ABBOTSFORD THIS EDITION OF THE NOVELS OF HER GREAT-GRANDFATHER WALTER SCOTT IS DEDICATED BY THE PUBLISHERS. <advertisement> ADVERTISEMENT. In printing this New Edition of the Waverley Novels, the Publishers have availed themselves of the opportunity thus afforded them of carefully collating it with the valuable interleaved copy in their possession, containing the Author's latest manuscript corrections and notes; and from this source they have obtained several annotations of considerable interest, never before published. As examples of some of the more important of these may be mentioned the notes on ``High Jinks'' in Guy Mannering, ``Pr<ae>torium'' in the Antiquary, and the ``Expulsion of the Scotch Bishops'' in the Heart of Midlothian. There have also been inserted (within brackets) some minor notes explanatory of references now rendered perhaps somewhat obscure by the lapse of time. For these, the Publishers have been chiefly indebted to Mr. David Laing, Secretary of the Bannatyne Club, and one of the few surviving friends of the Author. -

My Commonplace Book

QJarnell Unioeroitg ffiihtarg BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF HENRY W. SAGE 1891 Cornell University Library PN 6081.H12 3 1924 027 665 524 Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924027665524 MY COMMONPLACE BOOK MY COMMONPLACE BOOK T. HACKETT J. ^ " ' Omne meum, nihil meum T. FISHER UNWIN LTD LONDON : ADELPHI TERRACE n First publication in Great Britain .... 1919- memories ! O past that is ! George EuoT DEDICATED TO MY DEAR FRIEND RICHARD HODGSON WHO HAS PASSED OVER TO THE OTHER SIDE Of wounds and sore defeat I made my battle-stay ; Winged sandals for my feet I wove of my delay ; Of weariness and fear I made my shouting spear ; Of loss, and doubt, and dread, And swift oncoming doom I made a helmet for my head And a floating plume. From the shutting mist of death, From the failure of the breath I made a battle-horn to blow Across the vales of overthrow. O hearken, love, the battle-horn I The triumph clear, the silver scorn I O hearken where the echoes bring, Down the grey disastrous morn. * Laughter and rallying ! Wn^uAM Vaughan Moody. From Richard Hodgson's Christmas Card, 1904, the Christmu before bis death I cannot but remember such things were. That were most precious to me. Macbeth, IV, 3. PREFACE* A I/ARGE proportion of the most interesting quotations in this book was collected between 1874 and 1886. -

2020 International List of Protected Names

INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (only available on IFHA Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 03/06/21 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne-Billancourt, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org The list of Protected Names includes the names of : Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally renowned, either as main stallions and broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or jump) From 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf Since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf The main stallions and broodmares, registered on request of the International Stud Book Committee (ISBC). Updates made on the IFHA website The horses whose name has been protected on request of a Horseracing Authority. Updates made on the IFHA website * 2 03/06/2021 In 2020, the list of Protected -

May 19,1887.—20 A

The Republican Journal VOLUME 59. BELFAST, MAINE, THURSDAY, MAY 19, 1887. NUMBER 20. Street Scenes in a Mexican City. either on foot, on horse or in :i carriage, Maine Matters. Generalities. The Professor to His Critics. The French Spoliation Claims. The Capture of East port. Wintrrport Corn Factor). JOURNAL. would he ivm nted a< a deadly insult and ^i\e KKITBLICAX 1 TIIK The s sufficient cause fora duel, siiiee to the NEWS A X I> GOSSII* FKOM Al.I. OVKK Till. STATE, To tin: Editor of the Journal: I To Kldiuu of IHF J<d unai. All article, requisite number of acres of corn rs« i.iai.ti ij wnu li a-h »nisii \ s11: vm.i 1:. accept Vandals have marred the Washington monu- say, The Court of Claims resumed the considera- paving invitation would her from I»een the the I'nion Packing seriously compromise ment. Mr. T won copied your paper, which lias recently ap- ! pledged hy farmers, r.i.ism !• rm isi'.w moumm; i«v tiik < orrt spomlonee of the Journal. Rust, have the bet. It was a new tion of the French spoliation eases on 3. yrood name. A GOO]* STATE TO I.IVE IX. May ! Co. anti hat that I could peared in the Uoston Dailj Record as t<* the capture have closet! the lease of Central wharf (ir\I»AI A.lAliA. Will. Tile utilities of on all afternoons Pa., has a six feet again prod you into print in The delay has been due to the request of the 1 Apr. -

Mercyhurst Professor FRANCIS X. CONNOLLY to SPEAK AT

GOOD LUCK GRADUATES! GOOD LUCK GRADUATES! Volume XIX, No, 6 MERCYHURST COLLEGE, ERIE, PA. May—June, 1949 ALPHA ETA INSTALLED Mercyhurst Professor FRANCIS X. CONNOLLY TO SPEAK IsGiive n AT'COLLEGE Honorary Degree AT COMMENCEMENT EXERCISES fE ? r? £ranCT? ?' C9nno1 y. Professor of English Litera Banquet Opens Week End ture at Fordham University, New York City, will addrei the members of the Mercyhurst College graduating cfi!i at the annual commencement exercises in the Chapel of Christ the Ceremonies King on June 8 at 8:30 p.m. Dr. Connolly is chairman of the board of the Catholic Poetry Society of America as well as The Alpha Eta chapter of Kappa Omicron Phi was offic editor of the recent book, "Literature: The Channel of Cul ially installed at Mercyhurst during the weekend of May 28-29. ture. A beautifully appointed formal dinner, served in the state din The Rev. Edward P. Latimer, Ph. D., will present the candi ing room, was the first in a series of installation ceremonies. dates for degrees to His Excellency, the Most Reverend John After dinner the toast-master, Jean Tobin, introduced Mother Mark Gannon, Bishop of the Erie Diocese and Chancellor of M. Borgia, who welcomed the guests, Sister Rose Angela, Mercyhurst College, who will confer the degrees. Sister Rose Marie, Roberta Malone and Ann Kelch, all of Set- Those eligible for the degree of Bachelor of Arts include on Hill College, Greensburg, Pa., and Dr. Opal Rhodes and Mary Ann Black, Erie; Margaret Bodenschatz, Portage, Pa; Margaret Steadman of Indiana State Teachers College. -

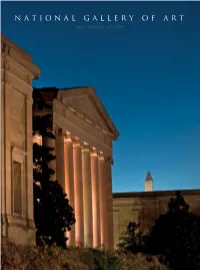

NGA | 2012 Annual Report

NA TIO NAL G AL LER Y O F A R T 2012 ANNUAL REPort 1 ART & EDUCATION Diana Bracco BOARD OF TRUSTEES COMMITTEE Vincent J. Buonanno (as of 30 September 2012) Victoria P. Sant W. Russell G. Byers Jr. Chairman Calvin Cafritz Earl A. Powell III Leo A. Daly III Frederick W. Beinecke Barney A. Ebsworth Mitchell P. Rales Gregory W. Fazakerley Sharon P. Rockefeller Doris Fisher John Wilmerding Juliet C. Folger Marina Kellen French FINANCE COMMITTEE Morton Funger Mitchell P. Rales Lenore Greenberg Chairman Frederic C. Hamilton Timothy F. Geithner Richard C. Hedreen Secretary of the Treasury Teresa Heinz Frederick W. Beinecke John Wilmerding Victoria P. Sant Helen Henderson Sharon P. Rockefeller Chairman President Benjamin R. Jacobs Victoria P. Sant Sheila C. Johnson John Wilmerding Betsy K. Karel Linda H. Kaufman AUDIT COMMITTEE Robert L. Kirk Frederick W. Beinecke Leonard A. Lauder Chairman LaSalle D. Leffall Jr. Timothy F. Geithner Secretary of the Treasury Edward J. Mathias Mitchell P. Rales Diane A. Nixon John G. Pappajohn Sharon P. Rockefeller Frederick W. Beinecke Mitchell P. Rales Victoria P. Sant Sally E. Pingree John Wilmerding Diana C. Prince Robert M. Rosenthal TRUSTEES EMERITI Roger W. Sant Robert F. Erburu Andrew M. Saul John C. Fontaine Thomas A. Saunders III Julian Ganz, Jr. Fern M. Schad Alexander M. Laughlin Albert H. Small David O. Maxwell Michelle Smith Ruth Carter Stevenson Benjamin F. Stapleton Luther M. Stovall Sharon P. Rockefeller John G. Roberts Jr. EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Ladislaus von Hoffmann Chief Justice of the Diana Walker United States Victoria P. Sant President Alice L. -

2008 International List of Protected Names

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities _________________________________________________________________________________ _ 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Avril / April 2008 Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : ) des gagnants des 33 courses suivantes depuis leur ) the winners of the 33 following races since their création jusqu’en 1995 first running to 1995 inclus : included : Preis der Diana, Deutsches Derby, Preis von Europa (Allemagne/Deutschland) Kentucky Derby, Preakness Stakes, Belmont Stakes, Jockey Club Gold Cup, Breeders’ Cup Turf, Breeders’ Cup Classic (Etats Unis d’Amérique/United States of America) Poule d’Essai des Poulains, Poule d’Essai des Pouliches, Prix du Jockey Club, Prix de Diane, Grand Prix de Paris, Prix Vermeille, Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe (France) 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Oaks, Derby, Ascot Gold Cup, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, St Leger, Grand National (Grande Bretagne/Great Britain) Irish 1000 Guineas, 2000 Guineas, Derby, Oaks, Saint Leger (Irlande/Ireland) Premio Regina Elena, Premio Parioli, Derby Italiano, Oaks (Italie/Italia)