Peace Education in the Philippines: Measuring Impact

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

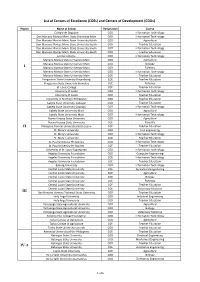

The Beacon Academy Faculty List Ay 2020-2021 1

THE BEACON ACADEMY FACULTY LIST AY 2020-2021 1. Mark Vincent Escaler Head of School MA Individualized Study – focus on Postmodern Philosophy & Film/Media Studies (Gallatin School of Individualized Study – New York University) 2. Maria Elena Paterno-Locsin Dean of Faculty & Acting Diploma Program/ Diploma Programme Senior High School Coordinator IB MYP School Visit Team Member Master of Education (Harvard University) DP English 3. Maria Teresa Roxas Dean of Students BA Anthropology (University of The Philippines) MYP Comparative Religion 4. Roy Aldrin Villegas Middle Years Program/Junior High School Coordinator BS Secondary Education (De La Salle University) MYP Biology, MYP Physics ---- 5. Natalie Albelar Guidance Counselor MA Counselling (De La Salle University) 6. Amor Andal Learning Support and Development Bachelor in Elementary Education, Major in Special Education (University of the Philippines) 7. Jose Badelles Arts Director AB Psychology (Ateneo De Manila University) DP Visual Arts THE BEACON ACADEMY FACULTY LIST AY 2020-2021 8. LeaH Joy Cabanban MA Education/ MA Business Management (University of the Philippines) DP Business and Management 9. Alfred Rey Capiral Fine Arts, Major in Painting (University of the Philippines) MYP Design, MYP Visual Arts 10. Helena Denise Clement College Counselor, Junior High School Bachelor of Business Administration (Loyola Marymount University) 11. Maria Celeste Coscolluela MA Creative Writing (University of the Philippines) DP English 12. Ana Maria David IB Examiner- Math Studies BS Industrial Engineering (Adamson University) DP Mathematics/Math Learning Support Teacher 13. Vian Claire Erasmo Guidance Counselor, Senior High School MA Counselling (Miriam College) 14. Ma. Concepcion Estacio Athletics Director B Communication Media Production (Assumption College) 15. -

To View Publication As A

International Institute on Peace Education (IIPE) & Community-Based Institutes on Peace Education (CIPE) Tony Jenkins, Co-Director, Peace Education Center, Teachers College, Columbia University, & Global Coordinator, International Institute on Peace Education INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE ON PEACE EDUCATION The International Institute on Peace Education (IIPE) was founded in 1982 and has since been held annually in different parts of the world. The first IIPE was held at Teachers College, Columbia University and organized by Professors Betty A. Reardon, Willard Jacobson and Douglas Sloan in cooperation with the United Ministries in Education. The IIPE is a multicultural and cooperative learning opportunity that has brought together educators and professionals from around the world to learn with and from each other in short-term learning communities that model principles of critical, participatory peace pedagogy. The Institute is an opportunity for networking and community building and has spawned a variety of collaborative research projects and peace education initiatives at the local, regional, and international levels. The International Peace Bureau, in nominating IIPE for the 2005 UNESCO Peace Education Prize described it as “probably the most effective agent for the introduction of peace education to more educators than any other single non-governmental agency.”(Weiss, 2005) The objectives of each particular institute are rooted in the needs and transformational concerns of the host region. More widely, the social purposes of the IIPE are directed toward the development of the field of peace education in theory, practice and advocacy. In addition to the important learning of contextually relevant issues and pedagogical approaches, the purposes of the IIPE are threefold: 1) To aid in the development of the substance of peace education through exploration of new and challenging themes to contribute to the on-going development of the field. -

2014 YCAR Annual Report

Annual Report 2013.2014 Annual Report 2013.2014 1. Contact Information Dr Philip Kelly, Director. [email protected] Dr Janice Kim, Associate Director. [email protected] Alicia Filipowich, Coordinator. [email protected] York Centre for Asian Research (YCAR) 8th Floor, Kaneff Tower || 416.736.5821 | http://ycar.apps01.yorku.ca/ | [email protected] 2. Home Faculties for Active YCAR Faculty and Graduate Associates Education (1) Environmental Studies (6) Fine Arts (9) Health (2) Liberal Arts and Professional Studies (111) Glendon College (5) Osgoode Hall Law School (3) Schulich School of Business (3) 3. Chartering First Charter: May 2002; Last Renewal: March 2010 (for six years) 4. Mandate YCAR’s mandate is to foster and support research at York related to East, Southeast and South Asia, and Asian migrant communities in Canada and around the world. The Centre aims to provide: 1) Intellectual Exchange: facilitating interaction between Asia‐focused scholars at York, and between York researchers and a global community of Asia scholars; 2) Research Support: assisting in the development of research grants, and administering such projects; 3) Graduate Training: supporting graduate student training and research by creating an interdisciplinary intellectual hub, administering a graduate diploma program, and providing financial support for graduate research; 4) Knowledge Mobilization: providing a clear public point of access to York’s collective research expertise on Asia, and ensuring the wider dissemination of York research on Asia to academic and non‐academic -

Name of Institution: Miriam College Address of the Institution: Katipunan Avenue, Loyola Heights, QC Website: Back

Name of Institution: Miriam College Address of the Institution: Katipunan Avenue, Loyola Heights, QC Website: www.mc.edu.ph Background of the Institution The story of Miriam College dates back to 1926 when the Archbishop of Manila, then Reverend Michael O’ Doherty, requested the Sisters of the Maryknoll Congregation in New York to initiate a teacher-training program for wom0en in the Philippines. In an old remodeled Augustinian Convent in Malabon, Rizal, the Malabon Normal School was established. The school transferred sites several times until finally in 1953, with its name officially changed to Maryknoll College, it laid down its permanent roots in Diliman (or Loyola Heights), Quezon City. Its graduates have distinguished themselves in various professions. Several have been cabinet secretaries, legislators, accomplished businesswomen, entrepreneurs, educators and leaders of government and nongovernmental organizations. To date, nineteen alumnae have been selected as “The Outstanding Women in the Nation’s Service” (TOWNS) awardees. After Vatican II, the Maryknoll congregation began to evaluate its work, not only in the Philippines but worldwide, in the light of their original apostolate as a missionary order. In the 60s, the Maryknoll congregation saw the readiness of the Filipino laity to continue the educational mission they had started. In 1977, the ownership and management of the school were turned over to lay administrators. In accordance with the agreement, the name Maryknoll was to be changed to pave the way for the promotion of the school’s unique identity, distinct although not disconnected from the identity of the Maryknoll sisters. In 1989, after a series of consultations, Maryknoll College was re-named Miriam College. -

One Hundred Eleventh Annual Spring Commencement

One Hundred Eleventh Annual Spring Commencement SATURDAY, MAY 5 2007 BEASLEY PERFORMING ARTS COLISEUM WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY PULLMAN, WASHINGTON Commencement Mission Statement Commencement at Washington State University represents the culmination of a student's academic achievement. It is a time for celebration and reflection for students, families, faculty, and staff. It brings together the campus community to share the joy of the accomplished goals of our students. The commencement ceremony at Washington State University serves a dual purpose: to mark a point of achievement, thus completing a chapter in the lives of students and those who support them, and to encourage continued pursuit of learning, personal fulfillment, and engagement with their local and worldwide communities. rt:Jn9v913 b91bnuH 9nQ :fn9m9Jn9mmo) Qni,q2 lsunnA '\00~ c. YAM YAOHUTA2 MU321JO) 2THA OV11M~O=:tH3q Y3J2A38 YTl2H3VIV1U 3TAT2 li1QT;:H11H2AW V10T;)V11H2AW V1AMJJUq to notJ:;r, nlL, "lrlJ 2Jn92•,nq91 V11n3 r,U <:11cll no1gnir1 ,6W 16 ,r "3!'!19.Jn"lrrm 110· '3 1 91 • r_ !c.1d9l9_ •ol .:i ·I lr l, Jn9rrr9v--w1':, Jt'TI9blD611,-,'lb·•lz,. lUqms, r 1:1 r"'J-.io' lpr. d JI sl. bns ,V:: 1Lo161, "li ;!''16 ,J"l"ltlU:ll ,., l11"l u:tz "JO t 1£.o b9r: ·,:i,no: ~- -Jr!:l v~· 9rl:l 91ui, "t vlrnunrroJ t.Ub , l oV"'3, VJ,_ JVlr J ~.6:' c nO!f2 :1arW J;; nOl"lC, 9> l, TI9', 1~ TifTll > ,!"~ "rl1 11 •11c.-. ·, ( ., J ,TI', ll' t ln"l ,v,1 )£,I> I, q 6 ,l16m 0, zoc. Jq b9un,Jnc,) ~E?61Li' ,,n ol br-c -n9·t IP". -

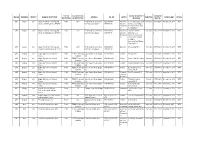

Region Province District Name of Institution Type of Institution Classification of Institution Address Tel. No. Sector Course/Re

TYPE OF CLASSIFICATION COURSE/REGISTERED PROGRAM REGION PROVINCE DISTRICT NAME OF INSTITUTION ADDRESS TEL. NO. SECTOR DURATION DATE ISSUED STATUS INSTITUTION OF INSTITUTION PROGRAM REG. NO. CAR Apayao Lone Apayao Provincial Technology and Public LGU Provincial Gov't. Center San 09204072877/ Automotive Service Small Engine and 168 Hours 20151502010 November 27, 2015 WTR Livelihood Training Center (APTLTC) Isidro Sur, Luna Apayao 09399078196 and Land Components Leading to 2 Transportati Motorcycle/Small Engine on Servicing NC II CAR Apayao Lone Apayao Provincial Technology and Public LGU Provincial Gov't. Center San 09204072877/ Automotive Perform Preventive 170 Hours 20151501010 November 27, 2015 WTR Livelihood Training Center (APTLTC) Isidro Sur, Luna Apayao 09399078196 and Land Maintenance on 3 Transportati Motorcycle Mechanical on and Electrical Systems Leading to Motorcycle/Small Engine Servicing NC II CAR Apayao Lone Apayao Provincial Technology and Public LGU Provincial Gov't. Center San 09204072877/ Garments Dressmaking NC II 166 hours 20151502210 November 27, 2015 WTR Livelihood Training Center (APTLTC) Isidro Sur, Luna Apayao 09399078196 4 CAR Benguet Lone Baguio City School of Arts and Public TESDA Technology Upper Session Road, Baguio (074) 444-8459 Tourism Asian Cuisine 118 Hours 20151503012 December 10, 2015 NTR Trades Institution City 0 CAR Benguet Lone Baguio City School of Arts and Public TESDA Technology Upper Session Road, Baguio (074) 444-8459 Tourism Advance Cake Decoration 120 Hours 20151503012 December 10, 2015 NTR -

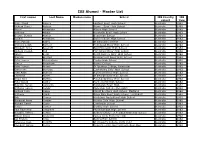

Coes) and Centers of Development (Cods) As of May 2016

Table 8. List of Centers of Excellence (COEs) and Centers of Development (CODs) as of May 2016 Region Name of Higher Education Institution (HEI) Institutional Type Designation Program NCR - National Capital Region Adamson University Private HEIs COD Chemical Engineering Civil Engineering Computer Engineering Electrical Engineering Electronics Engineering Industrial Engineering Teacher Education AMA University Private HEIs COD Information Technology Asia Pacific College Private HEIs COD Computer Engineering COE Information Technology Ateneo de Manila University Private HEIs COD Communication Electronics Engineering Environmental Science History Literature(Kagawaran ng Filipino) Political Science COE Biology Business Administration Chemistry Entrepreneurship Information Technology Literature (Dept of English) Mathematics Philosophy Physics Psychology Sociology Centro Escolar University Private HEIs COD Business Administration Optometry COE Teacher Education De La Salle College of Saint Benilde Private HEIs COE Business Administration Hotel and Restaurant Management De La Salle University Private HEIs COD Computer Engineering History Literature Political Science Statistics COE Accountancy Biology Business Administration Chemical Engineering Chemistry Civil Engineering Electronics Engineering Entrepreneurship Page 1 of 9 Region Name of Higher Education Institution (HEI) Institutional Type Designation Program Industrial Engineering Information Technology Mathematics Mechanical Engineering Physics Teacher Education Far Eastern University Private -

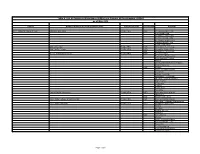

ISS Alumni - Master List

ISS Alumni - Master List First names Last Name Maiden name School ISS Country ISS cohort Year Brian David Aarons Fairfield Boys' High School Australia 1962 Richard Daniel Aldous Narwee Boys' High School Australia 1962 Alison Alexander Albury High School Australia 1962 Anthony Atkins Hurstville Boys' High School Australia 1962 George Dennis Austen Bega High School Australia 1962 Ronald Avedikian Enmore Boys' High School Australia 1962 Brian Patrick Bailey St Edmund's College Australia 1962 Anthony Leigh Barnett Homebush Boys' High School Australia 1962 Elizabeth Anne Beecroft East Hills Girls' High School Australia 1962 Richard Joseph Bell Fort Street Boys' High School Australia 1962 Valerie Beral North Sydney Girls' High School Australia 1962 Malcolm Binsted Normanhurst Boys' High School Australia 1962 Peter James Birmingham Casino High School Australia 1962 James Bradshaw Barker College Australia 1962 Peter Joseph Brown St Ignatius College, Riverview Australia 1962 Gwenneth Burrows Canterbury Girls' High School Australia 1962 John Allan Bushell Richmond River High School Australia 1962 Christina Butler St George Girls' High School Australia 1962 Bruce Noel Butters Punchbowl Boys' High School Australia 1962 Peter David Calder Hunter's Hill High School Australia 1962 Malcolm James Cameron Balgowlah Boys' High Australia 1962 Anthony James Candy Marcellan College, Randwich Australia 1962 Richard John Casey Marist Brothers High School, Maitland Australia 1962 Anthony Ciardi Ibrox Park Boys' High School, Leichhardt Australia 1962 Bob Clunas -

3 – Growth Centers

ANNEX 3 GROWTH CENTERS CBD-KNOWLEDGE COMMUNITY DISTRICT CUBAO GROWTH DISTRICT BATASAN-NGC GROWTH CENTER NOVLIHES-LAGRO GROWTH CENTER BALINTAWAK-MUNOZ GROWTH CENTER Annex 3: Growth Centers 1. CBD-KNOWLEDGE COMMUNITY DISTRICT 1.1. Area Coverage and Population The proposed CBD-Knowledge Community District has total area of 1,862 hectares and covers 22 barangays in Districts I, III and IV. It embraces the North, East, South and West triangles, UP Campus including the UP-Ayala Techno Hub, Ateneo de Manila University, Miriam College, Balara Filtration Plant, the vicinity of SM North EDSA and Veteran’s Memorial Medical Center and the residential communities in UP Village, Teacher’s Village, Pinyahan, Krus na Ligas, Malaya and Xavierville areas. 1.2. District Boundary The study area is bounded by the following: North: Area lot deep northside of Nueva Vizcaya St. and Road 3 up to lot deep westside of Mindanao Avenue then northward up to lot deep northside of Road 10 then eastward up to lot deep Westside of Visayas Avenue then northward up to lot deep northside of Central Avenue then eastward towards Commonwealth Avenue extending up to lot deep eastside of Katipunan Avenue. East: Area lot deep eastside of Katipunan Avenue going towards lot deep northside of Mactan St. then eastward towards lot deep eastside of Balintawak St. then southward to QC-Marikina politicalBoundary then westward through periphery of MWSS Balara Homesite up to MWSSAqueduct then southward up to lot deepEastside of Katipunan Avenue then Southward towards Mangyan St. and Eastward along southern periphery of LaVista Subdivision up to QC-Marikina politicalBoundary then southward up to Aurora Boulevard. -

Three Decades of Peace Education in the Philippines: Stories of Hope and Challenges Copyright © 2017 All Rights Reserved

INSIDE FRONT COVER BLANK PAGE Three Decades of Peace Education in the Philippines: Stories of Hope and Challenges Copyright © 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without per- mission in writing from the publishers and the authors except by a reviewer or researcher who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review or research for inclusion in any other publication. Published by the Center for Peace Education, Miriam College, Katipunan Ave., Quezon City, Philippines, and the World Council for Curriculum and Instruction, Philippines Chapter. Printed by Cover & Pages Publishing, Inc., Manila, Philippines. ISBN: 978-971-0177-12-7 iv Three Decades of Peace Education in the Philippines: Stories of Hope and Challenges Editors: Toh Swee-Hin • Virginia Cawagas • Jasmin N. Galace Assistant Editor: Anna Kristina M. Dinglasan Publishers: Center for Peace Education, Miriam College & World Council for Curriculum and Instruction, Philippines Chapter v 6 Three Decades of Peace Education in the Philippines: Stories of Hope and Challenges CONTENTS Preface .........................................................................................................ix Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Section I: Visions Crystallized, Seeds Planted Journeying in Solidarity: Educating for a Culture of Peace from Mindanao to Manila and Beyond by Toh Swee-Hin ................... 15 Peace Education: Reflections of a Mindanao Educator by Ofelia L. -

(Coes) and Centers of Development (Cods) IV-A

List of Centers of Excellence (COEs) and Centers of Development (CODs) Region Name of School Designation Course Colegio de Dagupan COD Information Technology Don Mariano Marcos Mem. State University-Main COD Information Technology Don Mariano Marcos Mem. State University-North COD Agriculture Don Mariano Marcos Mem. State University-North COD Teacher Education Don Mariano Marcos Mem. State University-South COD Information Technology Don Mariano Marcos Mem. State University-South COD Teacher Education Lorma Colleges COD Information Technology Mariano Marcos State University-Main COD Agriculture I Mariano Marcos State University-Main COD Biology Mariano Marcos State University-Main COD Forestry Mariano Marcos State University-Main COD Information Technology Mariano Marcos State University-Main COE Teacher Education Pangasinan State University-Bayambang COE Teacher Education Pangasinan State University-Binmaley COE Fisheries St. Louis College COE Teacher Education University of Luzon COD Information Technology University of Luzon COD Teacher Education University of Northern Philippines COD Teacher Education Isabela State University-Cabagan COD Teacher Education Isabela State University-Cauayan COD Information Technology Isabela State University-Main COD Agriculture Isabela State University-Main COD Information Technology Nueva Vizcaya State University COD Agriculture Nueva Vizcaya State University COE Forestry II Philippine Normal University-North Luzon COE Teacher Education St. Mary's University COD Civil Engineering St. Mary's University -

Core Skills for Teaching Peace, Conflict Resolution Education and Social Emotional Learning in the Classroom!

Core Skills for Teaching Peace, Conflict Resolution Education and Social Emotional Learning in the Classroom! Facilitators and Guest Presenters Facilitators: Jennifer Batton is the current Co-Chair, and past Chair, of the GPPAC Peace Education Working Group. She has 24 years of experience in the field of conflict resolution education (CRE) working for state government, higher education, and a non-profit to help local and global communities build their capacity to prevent, address, and manage conflict. Her experience includes eight years in state government (serving approximately 3600 primary and secondary public schools and 52 teacher training colleges and universities), seven years as the director of the Global Issues Resource Center at Cuyahoga Community College, and international education work in 23 countries. She provided direct service to more than 71 colleges and universities, 600 primary and secondary schools, and hundreds of civil society and governmental organizations. She teaches on-line undergraduate and graduate level teacher education for Cleveland State University and The University of Akron and currently serves as the Network Coordinator for 19 Ohio Colleges and Universities through the Ohio Peace and Conflict Studies Network. Lucy Nusseibeh lives and works in East Jerusalem. She is the founder and executive chair of Middle East Nonviolence and Democracy (MEND: www.mendonline.org) in East Jerusalem, pioneering promotion of awareness about the power of active nonviolence, especially work with schools and via innovative and educational uses of media. She is the chair of the Improving Practice working group at GPPAC and as such, a member of GPPAC’s Global Strategy Group,, “Preventing Violent Extremism” and the “Peace Education” Working Groups.