Vittoria Colonnese-Benni 150 DANTE and MACISTE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright Edinbugh University Press

chapter 1 Introduction: The Return of the Epic Andrew B. R. Elliott n the spring of 2000, some three decades after the well-publicised flops of ICleopatra (Mankiewicz 1963), The Fall of the Roman Empire (MannPress 1964) and The Greatest Story Ever Told (Stevens 1965), unsuspecting cinema audi- ences were once again presented with the lavish and costly historical epics which had ruled the box office a generation earlier. Ridley Scott’s Gladiator, in a seemingly sudden departure from many of Scott’s previous films, told the epic tale of a Roman general-turned-gladiator ‘who defied an emperor’ and who (albeit posthumously) founded a new Roman Republic. Though few could have predicted it at the time, the global success of his film ‘resurrected long-standing traditions of historical and cinematic spectacles’,1 and Scott would later find himself credited with re-launching a genreUniversity which had lain dormant for 35 years, heralding ‘a sudden resurrection of toga films after thirty-six years in disgrace and exile’, which prompted critics and scholars alike emphatically to declare the return of the epic.2 Indeed, looking back over the first decade of the twenty- first century, in terms of films and box-office takings the effect of this return is clear: in each year from 2000 to 2010, historical epics have made the top ten highest-grossing films, and attracted numerous awards and nominations.3 Accordingly,Copyright from Gladiator to The Immortals (Singh 2011), via Troy (Petersen 2004), Kingdom of Heaven (Scott 2005) and Alexander (Stone 2004), the decade came to be Edinbughcharacterised by a slew of historically-themed, costly, spectacular, lavish – in a word, ‘epic’ – films which, though not always as profitable as might have been hoped, performed respectably at the box office. -

Transgressive Masculinities in Selected Sword and Sandal Films Merle Kenneth Peirce Rhode Island College

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research and Major Papers Overview and Major Papers 4-2009 Transgressive Masculinities in Selected Sword and Sandal Films Merle Kenneth Peirce Rhode Island College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons Recommended Citation Peirce, Merle Kenneth, "Transgressive Masculinities in Selected Sword and Sandal Films" (2009). Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research and Major Papers Overview. 19. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/etd/19 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research and Major Papers at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses, Dissertations, Graduate Research and Major Papers Overview by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRANSGRESSIVE MASCULINITIES IN SELECTED SWORD AND SANDAL FILMS By Merle Kenneth Peirce A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Individualised Masters' Programme In the Departments of Modern Languages, English and Film Studies Rhode Island College 2009 Abstract In the ancient film epic, even in incarnations which were conceived as patriarchal and hetero-normative works, small and sometimes large bits of transgressive gender formations appear. Many overtly hegemonic films still reveal the existence of resistive structures buried within the narrative. Film criticism has generally avoided serious examination of this genre, and left it open to the purview of classical studies professionals, whose view and value systems are significantly different to those of film scholars. -

Italian Film Cylce to Be Shown at MOMA

_, FOB RELEASE: MONDAY THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART March ,, 1955 „ WBT 33 STMET, NIW YORK •». N. Y. £^ ^^ No. lo ITALIAN FITJI CYCLE TO BE SHOWN AT MUSEUM OF MODERN ART 50 YEARS OF ITALIAN CINEMA, the first survey of the development of the film in Italy to be shown in the United States, will be presented by the Film Library of the Museum of Modern Art beginning March 21, in the Museum's Auditorium, 11 West 53 Street, The retrospect, consisting of some thirty films, more than a third of which have never before been shown in the United States, is part of the Museum's 25th Anniversary year-long celebration. It marks as well the occasion of the 50th Anni versary of Italian films, the first of which, THE TAKING OF ROME, was produced in 1905* Films are shown ttice daily at 3 and 5130 p.m. In the Museum Auditorium. Commenting on the retrospect, Richard Griffith, Curator of the Film Library, says: "Twice in the course of motion picture history, Italian films have achieved world-wide fame and influence. Before the first World War, such spectacles as QUO VADIS? and CABIRIA brought the growing film medium to a new level of artistry, helped to establish its prestige, and deeply affected production everywhere -- their great length and colossal scale, for example, inspired D. W. Griffith to produce his THE BIRTH OF A NATION and INTOLERANCE. After the second War, OPEN CITY, PAISAN, BICYCLE THIEF, and other electrifying documents of "neo-realism" startled the world with their vitality and challenged film-makers of all nations by raising all the issues inherent in film form. -

Sieve Reeves, Sylvia Koscina. and Gabriele Anionini As Hfrnilfs, Lou-, ;Iiid Ulysses in Erróle Fin Rrgiva Cli Lidia Ílierfule.S Vitrliained)

.Sieve Reeves, Sylvia Koscina. and Gabriele Anionini as HfrnilfS, loU-, ;iiid Ulysses in Erróle fin rrgiva cli Lidia ílierfule.s Vitrliained). Note the "echoing effcci," as lolf and Ulys5t.s appear as ever more diminisbed and "impcrtt-ci" versions of Hercules. Pholofesf Gentlemen Prefer Hercules: Desire I Identification I Beefcake Robert A. Rushing Anyone Here for Love? One of the most memorable sequences in Howard Hawks's Gentle- men Prefer Blondes (US, 1953) is the musical number "Ain't There Anyone Here for Love?" Dorothy Shaw (Jane Russell) is accom- panying her friend Lorelei Lee (Marilyn Monroe) lo Piiris on a cruise across the Atlantic. While Lorelei is romantically involved with a wealthy young man, Dorothy is single—and lonely for some company. So she is only too happy to find tliiit the ship is filled with a team of handsome male athletes, bodybuilders, and gym- nasts. As Dorothy asks in an earlier scene, "The Olympic team? For me? Now wasn't thai thoughtful of somebody?" Her sense of tri- umph fades, iiouever, once the voyage is underway. The atbletes are in training and barely glance at her. The song's lyrics likewise revolve around this conflict between sports and sex: for instance, one stanza runs, "I'm apatbetic / and nonathletic / Can't keep up in a marathon / T need some shoulders to lean tipon / . Ain't there anyone here for love?" Love itself, oi course, is figured as a Camera Obicura 6g, Viilume 23, Number 3 IMII 10.1^15/02705346-2008-011 © 2008 hy Camera Oh.snuri Pulilishf d bv Duke Universitv Press '59 i()o . -

Where Can I Find Italian Silent Cinema? Ivo Blom 317 Chapter 30 Cinema on Paper: Researching Non-Filmic Materials Luca Mazzei 325

Italian Silent Cinema: AReader Edited by Giorgio Bertellini iv ITALIAN SILENT CINEMA: A READER British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Italian Silent Cinema: A Reader A catalogue entry for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 9780 86196 670 7 (Paperback) Cover: Leopoldo Metlicovitz’s poster for Il fuoco [The Fire, Itala Film, 1915], directed by Piero Fosco [Giovanni Pastrone], starring Pina Menichelli and Febo Mari. Courtesy of Museo Nazionale del Cinema (Turin). Credits Paolo Cherchi Usai’s essay, “A Brief Cultural History of Italian Film Archives (1980–2005)”, is a revised and translated version of “Crepa nitrato, tutto va bene”, that appeared in La Cineteca Italiana. Una storia Milanese ed. Francesco Casetti (Milan: Il Castoro, 2005), 11–22. Ivo Blom’s “All the Same or Strategies of Difference. Early Italian Comedy in International Perspective” is a revised version of the essay that was published with the same title in Il film e i suoi multipli/Film and Its Multiples, ed. Anna Antonini (Udine: Forum, 2003), 465–480. Sergio Raffaelli’s “On the Language of Italian Silent Films”, is a translation of “Sulla lingua dei film muti in Italia”, that was published in Scrittura e immagine. La didascalie nel cinema muto ed. Francesco Pitassio and Leonardo Quaresima (Udine: Forum, 1998), 187–198. These essays appear in this anthology by kind permission of their editors and publishers. Published by John Libbey Publishing Ltd, 3 Leicester Road, New Barnet, Herts EN5 5EW, United Kingdom e-mail: [email protected]; web site: www.johnlibbey.com Direct orders (UK and Europe): [email protected] Distributed in N. -

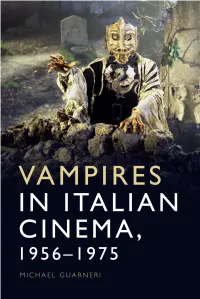

9781474458139 Vampires in It

VAMPIRES IN ITALIAN CINEMA, 1956–1975 66352_Guarneri.indd352_Guarneri.indd i 225/04/205/04/20 110:030:03 AAMM 66352_Guarneri.indd352_Guarneri.indd iiii 225/04/205/04/20 110:030:03 AAMM VAMPIRES IN ITALIAN CINEMA, 1956–1975 Michael Guarneri 66352_Guarneri.indd352_Guarneri.indd iiiiii 225/04/205/04/20 110:030:03 AAMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Michael Guarneri, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 10/12.5 pt Sabon by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 5811 5 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5813 9 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 5814 6 (epub) The right of Michael Guarneri to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 66352_Guarneri.indd352_Guarneri.indd iivv 225/04/205/04/20 110:030:03 AAMM CONTENTS Figures and tables vi Acknowledgements viii Introduction 1 PART I THE INDUSTRIAL CONTEXT 1. The Italian fi lm industry (1945–1985) 23 2. Italian vampire cinema (1956–1975) 41 PART II VAMPIRE SEX AND VAMPIRE GENDER 3. -

DIVAS, STARDOM, and CELEBRITY in MODERN ITALY Professor Allison Cooper [email protected] 207.798.4188 Dudley Coe 207

Spring, ‘18 ITAL/CINE 3077 Class meetings: Mondays, 6:30-9:25 pm in Mass Hall 105, McKeen Study Office hours: Mondays and Wednesdays, 3-4 pm and by appointment in Dudley Coe 207 DIVAS, STARDOM, AND CELEBRITY IN MODERN ITALY Professor Allison Cooper [email protected] 207.798.4188 Dudley Coe 207 Before there was Beyoncé there was Borelli; before Clooney there was Mastroianni; before Trump there was Berlusconi. The diva derives from Italy’s nineteenth-century opera, silent film, and Catholic culture. Today, she has evolved into a secular alternative to traditional female religious icons such as the Madonna and the Magdalene. Alongside the figure of the diva is that of her historical male counterpart, the divo, initially a sort of demigod in early Italian cinema who has now come to reflect contemporary Italy’s crisis of masculinity. Beyond their origins and evolution, the diva, divo, and modern star can ultimately be defined as performers who know how to play any role while superimposing their own image onto a character. “Divas, Stardom, and Celebrity in Modern Italy” examines in detail the question of how those images have been constructed, transmitted, and received from the late nineteenth century to the present day. A number of related questions will inform the course: How do different genres and modes of Italian film, from silent film, talkies, fascist propaganda films, and neorealism to comedy Italian style, the spaghetti western, and the horror film construct stars differently? How does stardom depend upon publicity, promotion, -

LE MÉPRIS, ULISSE, L'odissea Christian Pischel T

“INCLUDE ME OUT” – ODYSSEUS ON THE MARGINS OF EUROPEAN GENRE CINEMA: LE MÉPRIS, ULISSE, L’ODISSEA Christian Pischel The Diagram Homer’s Odyssey is considered one of the founding documents of Euro- pean literature. As we know, the text intertwines the motifs of the odys- sey or epic voyage, the intended homecoming, which is constantly being delayed and prevented by temptations and perils, and a structurally analogous narrative. Just as Odysseus traverses the world several times in search of Ithaca, the epic poem unites several temporal levels, narrative voices, and points of view until his return home, where the narrative does not end but culminates in the renewed and condensed mirroring of the entire process, the texture in all its to and fro and back and forth: Athena extends the night so that the reunited couple may tell each other the story of their twenty-year separation. Theresia Birkenhauer writes:1 The Odyssey is as artfully told as the narration is emphatically addressed in the epic. The hero’s labyrinthine parcours through uncanny spaces finds expression in the equally varied forms of discours, of narrative. In what follows, the epic quality of the material will serve as a backdrop against which I will explore three cinematic adaptations of the Odyssey. The films are the major Italo-American co-production Ulisse (Ulysses, 1954) directed by Mario Camerini, which is remembered today mainly because it starred Kirk Douglas, Le Mépris (Contempt, 1963) by Jean-Luc Godard, and a lesser-known eight-part television miniseries from 1968 entitled L’Odissea directed by Franco Rossi. -

20 Million Miles to Earth (1957) 130 2001: a Space Odyssey (1968

Index 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957) 130 Antoninus 87-8, 97, 98, Fig. 9 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) 37 Apollonius of Rhodes 69, 131, 132 300(2007) 39, 103,115, 120, 193,219, 220, Apuleius 158, 170 236-7 arena 34, 184-6, 221-2, 226, 229-33, Figs 7, 300 (graphic novel) 237 20 and 21 300 Spartans, The (1962) 5, 39, 101-24, Argona utica, myth of 69, 72, 75, 131 Figs 10 and 11; Cold War politics 105-7; Arms for Venus (play) 151 depiction of Sparta 112-18; marketing Armstrong, Todd 128, 134, 135 137; set-design 6-7, Fig. 2; reception Army of Darkness (1993) 125, 140 107-8; treatment of women 103, 118-21 art cinema 146-50 300 Spartans, The (comic) 109 Art Deco 24 81 2 (It.: Otto e Mezzo, 1963) 153, 157, 163 art, classical 161-2, 208, 209 Artemisia 116, 118, 120-1, 122, 123 A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Ascilto (Ascyltus) 151, 155, 158-60 the Fomm (1966) 172 At Lost the 1918 Show (television series) A Matter of Life and Death (1946) 126 177 Achilles (1995) 129, 215 Athena (1954) 72-3 Achilles 125, 173, 204, 215, 235 Athens 102, 103, 104, 106, 110, 116, 118, Actium, Battle of 21 124, 198 Adam's Rib (1923) 23 Atkinson, Rowan 182 Adventures of Robin Hood, The (1938) 178 Attila (1954) 63 Aeneid (Roman epic poem) 38, 130 Augustus Caesar (Octavian) 5, 21 , 27, 29, Aeschylus, Seuen against Thebes 75, 31, 69, 80, 184 Persians 148 Agora (2009) 80, 219 Bacchus, see Dionysus Aladdin (1992) 196-7, 201 Baldassare, Pasquali 167-8 Alcmene 163, 202, 213 Banton, Travis 25 Alexander (King of Macedon) 2, 20, 97-8, Ba ra, Theda 22 101, 104-5, 124 Barabbas -

The Roman Salute

The Roman Salute The Roman Salute Cinema, History, Ideology Martin M. Winkler THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PREss COLUMBus Copyright © 2009 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Winkler, Martin M. The Roman salute : cinema, history, ideology / Martin M. Winkler. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-0864-9 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-0864-9 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Rome—In motion pictures. 2. Rome—In art. 3. Rome—In literature. 4. Salutations. I. Title. PN1995.9.R68W56 2009 700'.45837 [22] 2008041124 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-0864-9) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9194-8) Cover design by Laurence J. Nozik Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Bembo Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the Ameri- can National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 contents Illustrations vii Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. History and Ideology: Half-Truths and Untruths 1 2. Ideology and Spectacle: The Importance of Cinema 6 3. About This Book 11 One Saluting Gestures in Roman Art and Literature 17 Two Jacques-Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii 42 Three Raised-Arm Salutes in the United States before Fascism: From the Pledge of Allegiance to Ben-Hur on Stage 57 Four Early Cinema: American and European Epics 77 Five Cabiria: The Intersection of Cinema and Politics 94 1. -

Steve Reeves, Sylvia Koscina, and Gabriele Anionini As Httriiles, Lou-, ;Iiid Ulysses in Frrotecui Trgiva Di Tjdin {Heriules Vitchained)

.Steve Reeves, Sylvia Koscina, and Gabriele Anionini as HtTriiles, loU-, ;iiid Ulysses in FrrotecUi trgiva di tJdin {Heriules Vitchained). Note the "echoing effcci," as lolf and Ulyssts appear as ever more diminished and "itripertt-ci" versions of Hercules. Pbolofesf Gentlemen Prefer Hercules: Desire I Identification I Beefcake Robert A. Rushing Anyone Here for Love? One of the most memorable seqtiences in Howard Hawks's Gentle- men Prefer Blondes (US, 1953) is the musical number "Ain't There Anyone Here for Love?" Dorothy Shaw (Jane Russell) is accom- panying her friend Lorelei Lee (Marilyn Monroe) lo Paris on a cruise across the Atlantic. While Lorelei is romantically involved with a wealthy young man, Dorothy is single—and lonely for some company. So she is only too happy to find that the ship is filled with a team of handsome male athletes, bodybuilders, and gytn- nasts. As Dorothy asks in an earlier scene, "The Olympic team? For me? Now wasn't thai thoughtful of somebody?" Her sense of tri- umph fades, iiowever, once the voyage is underway. The athletes are in training and barely glance at her. The song's lyrics likewise revolve around this conflict between spot ts and sex: for instance, one stanza runs, "I'm apatbetic / and nonathletic / Can't keep tip in a marathon / I need some shoulders to lean iipon / . Ain't there anyotie here for love?" Love itself, of course, is figured as a Camera Obscura 6g. Viilume 23, Number 3 IMII 10.1^15/02705346-2008-011 © 2008 hy Camera Oh.snuri Ptibli.shf d bv Duke Universitv Press '59 i()o . -

A Course on Classical Mythology in Film Author(S): James J

A Course on Classical Mythology in Film Author(s): James J. Clauss Source: The Classical Journal, Vol. 91, No. 3 (Feb. - Mar., 1996), pp. 287-295 Published by: The Classical Association of the Middle West and South Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3297607 Accessed: 23/09/2010 17:24 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=camws. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Classical Association of the Middle West and South is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Classical Journal. http://www.jstor.org A COURSEON CLASSICALMYTHOLOGY IN FILM n the twentiethcentury, as has often been observed,film has taken the place that narrative and dramatic poetry once had in the ancient world.