Wheelchair Use and Services in Kenya and Philippines: a Cross-Sectional Study Acknowledgments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION Child & Youth Welfare (Residential) ACCREDITED a HOME for the ANGELS CHILD Mrs

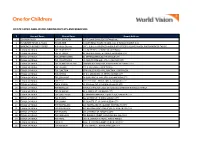

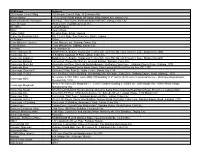

Directory of Social Welfare and Development Agencies (SWDAs) with VALID REGISTRATION, LICENSED TO OPERATE AND ACCREDITATION per AO 16 s. 2012 as of March, 2015 Name of Agency/ Contact Registration # License # Accred. # Programs and Services Service Clientele Area(s) of Address /Tel-Fax Nos. Person Delivery Operation Mode NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION Child & Youth Welfare (Residential) ACCREDITED A HOME FOR THE ANGELS CHILD Mrs. Ma. DSWD-NCR-RL-000086- DSWD-SB-A- adoption and foster care, homelife, Residentia 0-6 months old NCR CARING FOUNDATION, INC. Evelina I. 2011 000784-2012 social and health services l Care surrendered, 2306 Coral cor. Augusto Francisco Sts., Atienza November 21, 2011 to October 3, 2012 abandoned and San Andres Bukid, Manila Executive November 20, 2014 to October 2, foundling children Tel. #: 562-8085 Director 2015 Fax#: 562-8089 e-mail add:[email protected] ASILO DE SAN VICENTE DE PAUL Sr. Enriqueta DSWD-NCR RL-000032- DSWD-SB-A- temporary shelter, homelife Residentia residential care -5- NCR No. 1148 UN Avenue, Manila L. Legaste, 2010 0001035-2014 services, social services, l care and 10 years old (upon Tel. #: 523-3829/523-5264/522- DC December 25, 2013 to June 30, 2014 to psychological services, primary community-admission) 6898/522-1643 Administrator December 24, 2016 June 29, 2018 health care services, educational based neglected, Fax # 522-8696 (Residential services, supplemental feeding, surrendered, e-mail add: [email protected] Care) vocational technology program abandoned, (Level 2) (commercial cooking, food and physically abused, beverage, transient home) streetchildren DSWD-SB-A- emergency relief - vocational 000410-2010 technology progrm September 20, - youth 18 years 2010 to old above September 19, - transient home- 2013 financially hard up, (Community no relative in based) Manila BAHAY TULUYAN, INC. -

Taguig City Rivers and Waterways

Taguig City Rivers and Waterways This is not an ADB material. The views expressed in this document are the views of the author/s and/or their organizations and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Asian Development Bank, or its Board of Governors, or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy and/or completeness of the material’s contents, and accepts no responsibility for any direct or indirect consequence of their use or reliance, whether wholly or partially. Please feel free to contact the authors directly should you have queries. Outline Taguig waterways Issues and concerns A. Informal settlers B. Solid waste C. Waste water D. Erosion Actions Taken TAGUIG CITY LENGTH OF RIVER/CREEK LOCATION LENGTH WIDTH 1 Bagumbayan River 1,700 m 15.00 m 2 Mauling Creek 950 m 10.00 m 3 Conga Creek 3,750 m 8.00 m 4 Old conga Creek 1,400 m 5.00 m 5 Hagonoy River 1,100 m 10.00 m 6 Daang Kalabao Creek 2,750 m 10.00 m 7 Sapang malaki creek 650 m 10.00 m 8 Sapang Ususan Creek 1,720 m 10.00 m 9 Maysapang Creek 420 m 10.00 m 10 Commando Creek 300 m 5.00 m 11 Pinagsama Creek 1,650 m 8.00 m 12 Palingon Creek 340 m 10.00 m 13 Maricaban Creek 2,790 m 10.00 m 14 Pagadling Creek 740 m 10.00 m 15 Taguig River 3,000 m 50.00 m 16 Tipas River 1,360 m 20.00 m 17 Sukol Creek 800 m 10.00 m 18 Daang Manunuso Creek 740 m 10.00 m 19 Ibayo Creek 1,500 m 5.00 m 20 Sto. -

Building a Disaster Resilient Quezon City Project

Building a Disaster Resilient Quezon City Project Hazards, Vulnerability and Risk Assessment Report 22 May 2013 Earthquakes and Megacities Initiative Earthquakes and Megacities Initiative Puno Building, 47 Kalayaan Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City, Metro Manila, Philippines 1101 T/F: +632 9279643; T: +632 4334074 www.emi-megacities.org Hazards, Vulnerability and Risk Assessment Report and City Risk Atlas Building a Disaster Resilient Quezon City Project 22 May 2013 4 Quezon CityQuezon Project EMI Research Team QCG Contributors Dr. Eng. Fouad Bendimerad, Risk Assessment Hon. Herbert M. Bautista, City Mayor, QCG Task Leader, Project Director, EMI Gen. Elmo DG San Diego (Ret.), Head, DPOS Dr. Bijan Khazai, Risk Assessment and ICT and QC DRRMC Action O#cer, Project Expert, EMI Director, QCG Building a Disaster Resilient Building a Disaster Mr. Jerome Zayas, Project Manager, EMI Mr. Tomasito Cruz, Head, CPDO, QCG Ms. Joyce Lyn Salunat-Molina, Co-Project Ms. Consolacion Buenaventura, DPOS, Project Manager, EMI Manager, QCG Ms. Ma. Bianca Perez, Project Coordinator, EMI Dr. Noel Lansang, DPOS, Project Coordinator, Mr. Leigh Lingad, GIS Specialist, EMI QCG Mr. Kristo!er Dakis, GIS Specialist, EMI Project Technical Working Group Ms. Lalaine Bergonia, GIS Specialist, EMI Engr. Robert Beltran, Department of Ms. Bernie Magtaas, KDD Manager, EMI Engineering, Data Cluster Head, QCG Ms. Marivic Barba, Research Assistant for Engr. Robert Germio, PDAD, Data Cluster DRRM, EMI Head, QCG Ms. Ishtar Padao, Research Assistant for DRRM, Dr. Esperanza Arias, Quezon City Health EMI Department, Data Cluster Head, QCG Mr. Lluis Pino, Graduate Intern, EMI Karl Michael Marasigan, DPOS, Data Cluster Mr. Eugene Allan Lanuza, Junior GIS Analyst, EMI Head, QCG Ms. -

No. Company Star

Fair Trade Enforcement Bureau-DTI Business Licensing and Accreditation Division LIST OF ACCREDITED SERVICE AND REPAIR SHOPS As of November 30, 2019 No. Star- Expiry Company Classific Address City Contact Person Tel. No. E-mail Category Date ation 1 (FMEI) Fernando Medical Enterprises 1460-1462 E. Rodriguez Sr. Avenue, Quezon City Maria Victoria F. Gutierrez - Managing (02)727 1521; marivicgutierrez@f Medical/Dental 31-Dec-19 Inc. Immculate Concepcion, Quezon City Director (02)727 1532 ernandomedical.co m 2 08 Auto Services 1 Star 4 B. Serrano cor. William Shaw Street, Caloocan City Edson B. Cachuela - Proprietor (02)330 6907 Automotive (Excluding 31-Dec-19 Caloocan City Aircon Servicing) 3 1 Stop Battery Shop, Inc. 1 Star 214 Gen. Luis St., Novaliches, Quezon Quezon City Herminio DC. Castillo - President and (02)9360 2262 419 onestopbattery201 Automotive (Excluding 31-Dec-19 City General Manager 2859 [email protected] Aircon Servicing) 4 1-29 Car Aircon Service Center 1 Star B1 L1 Sheryll Mirra Street, Multinational Parañaque City Ma. Luz M. Reyes - Proprietress (02)821 1202 macuzreyes129@ Automotive (Including 31-Dec-19 Village, Parañaque City gmail.com Aircon Servicing) 5 1st Corinthean's Appliance Services 1 Star 515-B Quintas Street, CAA BF Int'l. Las Piñas City Felvicenso L. Arguelles - Owner (02)463 0229 vinzarguelles@yah Ref and Airconditioning 31-Dec-19 Village, Las Piñas City oo.com (Type A) 6 2539 Cycle Parts Enterprises 1 Star 2539 M-Roxas Street, Sta. Ana, Manila Manila Robert C. Quides - Owner (02)954 4704 iluvurobert@gmail. Automotive 31-Dec-19 com (Motorcycle/Small Engine Servicing) 7 3BMA Refrigeration & Airconditioning 1 Star 2 Don Pepe St., Sto. -

Population by Barangay National Capital Region

CITATION : Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population Report No. 1 – A NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION (NCR) Population by Province, City, Municipality, and Barangay August 2016 ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 1 – A 2015 Census of Population Population by Province, City, Municipality, and Barangay NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 Presidential Proclamation No. 1269 Philippine Statistics Authority TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword v Presidential Proclamation No. 1269 vii List of Abbreviations and Acronyms xi Explanatory Text xiii Map of the National Capital Region (NCR) xxi Highlights of the Philippine Population xxiii Highlights of the Population : National Capital Region (NCR) xxvii Summary Tables Table A. Population and Annual Population Growth Rates for the Philippines and Its Regions, Provinces, and Highly Urbanized Cities: 2000, 2010, and 2015 xxxi Table B. Population and Annual Population Growth Rates by Province, City, and Municipality in National Capital Region (NCR): 2000, 2010, and 2015 xxxiv Table C. Total Population, Household Population, -

2015Suspension 2008Registere

LIST OF SEC REGISTERED CORPORATIONS FY 2008 WHICH FAILED TO SUBMIT FS AND GIS FOR PERIOD 2009 TO 2013 Date SEC Number Company Name Registered 1 CN200808877 "CASTLESPRING ELDERLY & SENIOR CITIZEN ASSOCIATION (CESCA)," INC. 06/11/2008 2 CS200719335 "GO" GENERICS SUPERDRUG INC. 01/30/2008 3 CS200802980 "JUST US" INDUSTRIAL & CONSTRUCTION SERVICES INC. 02/28/2008 4 CN200812088 "KABAGANG" NI DOC LOUIE CHUA INC. 08/05/2008 5 CN200803880 #1-PROBINSYANG MAUNLAD SANDIGAN NG BAYAN (#1-PRO-MASA NG 03/12/2008 6 CN200831927 (CEAG) CARCAR EMERGENCY ASSISTANCE GROUP RESCUE UNIT, INC. 12/10/2008 CN200830435 (D'EXTRA TOURS) DO EXCEL XENOS TEAM RIDERS ASSOCIATION AND TRACK 11/11/2008 7 OVER UNITED ROADS OR SEAS INC. 8 CN200804630 (MAZBDA) MARAGONDONZAPOTE BUS DRIVERS ASSN. INC. 03/28/2008 9 CN200813013 *CASTULE URBAN POOR ASSOCIATION INC. 08/28/2008 10 CS200830445 1 MORE ENTERTAINMENT INC. 11/12/2008 11 CN200811216 1 TULONG AT AGAPAY SA KABATAAN INC. 07/17/2008 12 CN200815933 1004 SHALOM METHODIST CHURCH, INC. 10/10/2008 13 CS200804199 1129 GOLDEN BRIDGE INTL INC. 03/19/2008 14 CS200809641 12-STAR REALTY DEVELOPMENT CORP. 06/24/2008 15 CS200828395 138 YE SEN FA INC. 07/07/2008 16 CN200801915 13TH CLUB OF ANTIPOLO INC. 02/11/2008 17 CS200818390 1415 GROUP, INC. 11/25/2008 18 CN200805092 15 LUCKY STARS OFW ASSOCIATION INC. 04/04/2008 19 CS200807505 153 METALS & MINING CORP. 05/19/2008 20 CS200828236 168 CREDIT CORPORATION 06/05/2008 21 CS200812630 168 MEGASAVE TRADING CORP. 08/14/2008 22 CS200819056 168 TAXI CORP. -

Republic of the Philippines Metro Manila Flood Management Project

PD 0023-PHL September 27, 2017 PROJECT DOCUMENT OF THE ASIAN INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENT BANK Republic of the Philippines Metro Manila Flood Management Project This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without AIIB authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (As of September 1, 2017) Currency Unit - Philippine Peso (PhP) PhP 1.00 = US$0.019 PhP51.16 = US$1.00 FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AIIB Asia Infrastructure Investment KSA Key Shelter Agencies Bank LGU Local Government Units ASEAN Association of South East LLDA Laguna Lake Development Asian Nations Authority COA Commission on Audits MDB Multilateral Development CSCAND Collective Strengthening on Bank Community Awareness on MIS Management Information National Disasters System CSOs Civil Society Organizations MM Metro Manila DDR Due Diligence Report MMDA Metro Manila Development DENR Department of Environment Authority and Natural Resources MoA Memorandum of Agreement DPWH Department of Public Works NAMRIA National Mapping and and Highways Resource Information ERR Economic rate of return Authority ESIA Environmental and Social NCR National Capital Region Impact Assessment NEDA National Economic and ESMF Environmental and Social Development Authority Management Framework NHA National Housing Authority ESMP Environmental and Social NPV Net present value Management Plan O&M Operation and maintenance FCMC Flood Control Management OP/BP Operational -

National Capital Regional Office

Republic of the Philippines Department of Health NATIONAL CAPITAL REGIONAL OFFICE Annual Report January 1 – December 31, 2017 ADVANCE COPY DENGUE SURVEILLANCE REPORT FINDINGS: Partial reports showed there were 26,032 cases admitted at different reporting institutions of the Region from January 1 to December 31, 2017. There were 298 admissions for this week. Quezon City has the highest (33.48/10,000 population) attack rate (Table 2). 159 deaths were reported (CFR 0.61) (Table 1/Figure 1). This is 53% higher compared to the same period last year (16,977) [Table 1/Figure 2]; and 17% higher than previous five-year average (2012- 2016) [Figure 3]. Table 1. Distribution of Dengue Cases and Deaths by LGU (N=26,032) National Capital Region, January 1 – December 31, 2017 Cases Change 2017 LGU Rate 2016 2017 (%) Deaths CFR (%) Quezon City† 4,942 9,862 100 86 0.87 Caloocan City† 1537 3,184 107 11 0.35 Manila City† 2,677 2,816 5 7 0.25 Parañaque City† 1,043 1,661 59 8 0.48 Pasig City† 1,352 1,360 1 5 0.37 Makati City† 713 1,224 72 10 0.82 Valenzuela City† 693 1,022 47 2 0.20 Taguig City* 601 834 39 15 1.80 Malabon City† 516 830 61 4 0.48 Las Piñas City† 561 785 40 3 0.38 Marikina City† 442 666 51 5 0.75 Muntinlupa City† 320 389 22 2 0.51 Mandaluyong City 637 388 -39 0 0.00 San Juan City† 277 367 32 1 0.27 Navotas City† 192 307 60 0 0.00 Pasay City 368 288 -22 0 0.00 Pateros 106 49 -54 0 0.00 N C R 16,977 26,032 53 159 0.61 *Case-Fatality Rate should be less than 1.0 †Increase number of cases Disclaimer: Figures from previous report may differ due to late reports submitted and further verification. -

List of Ecpay Cash-In Or Loading Outlets and Branches

LIST OF ECPAY CASH-IN OR LOADING OUTLETS AND BRANCHES # Account Name Branch Name Branch Address 1 ECPAY-IBM PLAZA ECPAY- IBM PLAZA 11TH FLOOR IBM PLAZA EASTWOOD QC 2 TRAVELTIME TRAVEL & TOURS TRAVELTIME #812 EMERALD TOWER JP RIZAL COR. P.TUAZON PROJECT 4 QC 3 ABONIFACIO BUSINESS CENTER A Bonifacio Stopover LOT 1-BLK 61 A. BONIFACIO AVENUE AFP OFFICERS VILLAGE PHASE4, FORT BONIFACIO TAGUIG 4 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HEAD OFFICE 170 SALCEDO ST. LEGASPI VILLAGE MAKATI 5 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BF HOMES 43 PRESIDENTS AVE. BF HOMES, PARANAQUE CITY 6 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BETTER LIVING 82 BETTERLIVING SUBD.PARANAQUE CITY 7 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_COUNTRYSIDE 19 COUNTRYSIDE AVE., STA. LUCIA PASIG CITY 8 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_GUADALUPE NUEVO TANHOCK BUILDING COR. EDSA GUADALUPE MAKATI CITY 9 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HERRAN 111 P. GIL STREET, PACO MANILA 10 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_JUNCTION STAR VALLEY PLAZA MALL JUNCTION, CAINTA RIZAL 11 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_RETIRO 27 N.S. AMORANTO ST. RETIRO QUEZON CITY 12 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_SUMULONG 24 SUMULONG HI-WAY, STO. NINO MARIKINA CITY 13 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP 10TH 245- B 1TH AVE. BRGY.6 ZONE 6, CALOOCAN CITY 14 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP B. BARRIO 35 MALOLOS AVE, B. BARRIO CALOOCAN CITY 15 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP BUSTILLOS TIWALA SA PADALA L2522- 28 ROAD 216, EARNSHAW BUSTILLOS MANILA 16 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CALOOCAN 43 A. MABINI ST. CALOOCAN CITY 17 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CONCEPCION 19 BAYAN-BAYANAN AVE. CONCEPCION, MARIKINA CITY 18 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP JP RIZAL 529 OLYMPIA ST. JP RIZAL QUEZON CITY 19 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP LALOMA 67 CALAVITE ST. -

APM Name Address 350 Arcade Comm'l Bldg 350 Arcade Comm'l Bldg, 15 Sunflower Rd Atrium Makati 1773 CGII-ATRIUM Makati GF Atrium Bldg

APM Name Address 350 Arcade Comm'l Bldg 350 Arcade Comm'l Bldg, 15 Sunflower Rd Atrium Makati 1773 CGII-ATRIUM Makati GF Atrium Bldg. Makati Ave, Makati City Author Solutions TGU tower 6th Floor, TGU Tower, Asiatown Business Park, Lahug, Cebu City Azure Bicutan West service road Bicutan Exit slex BC Office Lopez Building Black Asun's House Caltex SLEX S Luzon Expy, Biñan, Laguna Caltex Southwoods (nav) Blk. 7 Lot 9 Brgy. San Francisco, Biñan, Laguna CCN (Nav) Office Cebu Mitsumi- Canteen Cebu Mitsumi, Inc. Sabang, Danao City Cebu-Mitsumi Cebu Mitsumi Inc, Sabang, Danao City City Hall F.B. Harrison St. Converg Baguio B Building No A, Baguio- AyalaLand TechnoHub, John Hay Special Economic Zone, Baguio City 2600 Convergys - i2 i2 Building, Asiatown IT Park, Lahug, Cebu City Convergys baguio A Building No A, Baguio- AyalaLand TechnoHub, John Hay Special Economic Zone, Baguio City 2600 Convergys Banawa Convergys, Paseo San Ramon, Arcenas Estates, Banawa, Cebu City Convergys Block 44 Ground to 3rd Floor, Block 44 Northbridgeway, Northgate Cyberzone. , Alabang Zapote Road, Alabang, 1770 Convergys Eton 7F, Three Cyberpod Centris North Tower, Eton Centris EDSA cor Quezon Ave. QC 1100 Convergys Glorietta 5 Glorietta 5 Bldg. East St., Ayala Center, Makati City 1224 Convergys I Hub 2 6th - 9th Floor, IHub 2 Building, Northbridgeway, Northgate Cyberzone, Alabang-Zapote Road, Alabang, 1770 Mezzanine & 10th 19th Floors, MDC 100 Building, C.P. Garcia (C-5) corner Eastwood Avenue, Barangay Bagumbayan, Convergys MDC Quezon City, 1110 8th to 11th Floors SM Megamall I.T. Center, Carpark Building C, EDSA cor. Julia Vargas Ave., Wack-Wack Village, Convergys Megamall Mandaluyong City Convergys Nuvali One Evotech Building Nuvali Lakeside Evozone Santa Rosa-Tagaytay Road Santa Rosa, Province of Laguna 4026 Convergys One Ground to 8th Floor, 6796 Ayala Avenue cor. -

CONSTITUTION of the REPUBLIC of the PHILIPPINES Document Date: 1986

Date Printed: 01/14/2009 JTS Box Number: 1FES 29 Tab Number: 37 Document Title: THE CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES Document Date: 1986 Document Country: PHI Document Language: ENG IFES 10: CON00159 Republic of the Philippines The Constitutional Commission of 1986 The- Constitution ,- of.the- -Republic of tile Philippines Adopted by , - . THE CONSTITIJTIONAL COMMISSION OF 1986 At the National Government-Center, Quezon City, Philjppincs, on the fifteenth day of October, Nineteen hundred and eighty-six 198(j THE CONSTITUTION· OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES P REAM B LE. We; toe sovereign Filipino people, imploring the aid of Almighty Cod, in order to build a just and humane society and establish a Government that shall embody our ideals and aspirations, promotl' the common good, conserve and. develop· our patrimony, and secure- to ourselves and our posterity the blessings of independence and democracy under the rule of law"and a regime of truth, justice, free dom, love, equality, and peace, do ordain and piomulgatethis Consti tution. ARTICLE I NATIONAL TERRITORY The national territorycomprise~ the Philippine archipelago, with all the islands and waters embraced therein,' and all other territories over which the. Philippines has sovereignty or jurisdiction, .consisting of its terrestrial, fluvial, and aerial domains, including its territorial sea, the seabed, the subsoil, the insula~ shelves, and other submarine areas. The waters aroilnd, between, and connecting the islands of the archipelago, regardless of their breadth and. dimensions, form part of the internal waters of the Philippines. ARTICLE II r DECLARATION OF PRINCIPLE15 AND STATE POLICIES PRINCIPLES Section I .. The Philippines is a democratic and· republican State. -

BB 1 (DP 10-30-12).Pdf

AMENDED ANNEX B: NUMBER OF SAMPLES FOR THE HOUSEHOLD INTERVIEW SURVEY Number of Province City / Municipality Barangay Total Population Sample Size Households NCR City of Mandaluyong Addition Hills 90,556 22,292 223 Bagong Silang 5,446 1,341 13 Barangka Drive 12,216 3,007 30 Barangka Ibaba 9,082 2,236 22 Barangka Ilaya 5,783 1,424 14 Barangka Itaas 10,875 2,677 27 Burol 2,826 696 7 Buayang Bato 1,663 409 4 Daang Bakal 4,818 1,186 12 Hagdang Bato Itaas 10,572 2,602 26 Hagdang Bato Libis 7,053 1,736 17 Harapin Ang Bukas 4,049 997 10 Highway Hills 26,110 6,427 64 Hulo 21,163 5,210 52 Mabini-J. Rizal 8,702 2,142 21 Malamig 7,044 1,734 17 Mauway 27,902 6,868 69 Namayan 6,416 1,579 16 New Zañiga 7,128 1,755 18 Old Zañiga 8,549 2,104 21 Pag-asa 4,167 1,026 10 Plainview 24,003 5,909 59 Pleasant Hills 5,046 1,242 12 Poblacion 15,409 3,793 38 San Jose 6,581 1,620 16 Vergara 4,412 1,086 11 Wack-wack Greenhills 9,495 2,337 23 Subtotal 347,066 85,435 852 City of Pasig Bagong Ilog 16,676 3,977 40 Bagong Katipunan 1,150 274 4 Bambang 19,208 4,581 46 Buting 10,517 2,508 25 Caniogan 27,242 6,497 65 Dela Paz 21,155 5,045 50 Number of Province City / Municipality Barangay Total Population Sample Size Households Kalawaan 27,393 6,533 65 Kapasigan 5,687 1,356 14 Kapitolyo 12,414 2,961 30 Malinao 4,722 1,126 11 Manggahan 43,647 10,409 104 Maybunga 33,307 7,943 79 Oranbo 4,028 961 10 Palatiw 19,047 4,542 45 Pinagbuhatan 144,371 34,431 344 Pineda 20,910 4,987 50 Rosario 60,563 14,443 144 Sagad 6,792 1,620 16 San Antonio 16,408 3,913 39 San Joaquin 13,642 3,253