Vergilian Allusions in the Novels of Willa Cather

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

If You Like My Ántonia, Check These Out!

If you like My Ántonia, check these out! This event is part of The Big Read, an initiative of the National Endowment for the Arts in partnership with the Institute of Museum and Library Services and Arts Midwest. Other Books by Cather About Willa Cather Alexander's Bridge (CAT) Willa Cather: The Emerging Voice Cather's first novel is a charming period piece, a love by Sharon O'Brien (920 CATHER, W.) story, and a fatalistic fable about a doomed love affair and the lives it destroys. Willa Cather: A Literary Life by James Leslie Woodress (920 CATHER, W.) Death Comes for the Archbishop (CAT) Cather's best-known novel recounts a life lived simply Willa Cather: The Writer and her World in the silence of the southwestern desert. by Janis P. Stout (920 CATHER, W.) A Lost Lady (CAT) Willa Cather: The Road is All This Cather classic depicts the encroachment of the (920 DVD CATHER, W.) civilization that supplanted the pioneer spirit of Nebraska's frontier. My Mortal Enemy (CAT) First published in 1926, this is Cather's sparest and most dramatic novel, a dark and oddly prescient portrait of a marriage that subverts our oldest notions about the nature of happiness and the sanctity of the hearth. One of Ours (CAT) Alienated from his parents and rejected by his wife, Claude Wheeler finally finds his destiny on the bloody battlefields of World War I. O Pioneers! (CAT) Willa Cather's second novel, a timeless tale of a strong pioneer woman facing great challenges, shines a light on the immigrant experience. -

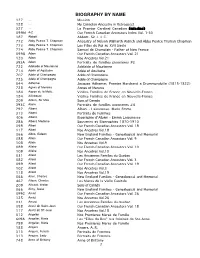

Biography by Name 127

BIOGRAPHY BY NAME 127 ... Missing 128 ... My Canadian Ancestry in Retrospect 327 ... Le Premier Cardinal Canadien (missing) 099M A-Z Our French Canadian Ancestors Index Vol. 1-30 187 Abbott Abbott, Sir J. J. C. 772 Abby Pearce T. Chapman Ancestry of Nelson Wilmarth Aldrich and Abby Pearce Truman Chapman 773 Abby Pearce T. Chapman Les Filles du Roi au XVII Siecle 774 Abby Pearce T. Chapman Samuel de Champlain - Father of New France 099B Adam Our French Canadian Ancestors Vol. 21 120 Adam Nos Ancetres Vol.21 393A Adam Portraits de familles pionnieres #2 722 Adelaide of Maurienne Adelaide of Maurienne 714 Adele of Aquitaine Adele of Aquitaine 707 Adele of Champagne Adele of Champagne 725 Adele of Champagne Adele of Champagne 044 Adhemar Jacques Adhemar, Premier Marchand a Drummondville (1815-1822) 728 Agnes of Merania Agnes of Merania 184 Aigron de la Motte Vieilles Familles de France en Nouvelle-France 184 Ailleboust Vieilles Familles de France en Nouvelle-France 209 Aitken, Sir Max Sons of Canada 393C Alarie Portraits de familles pionnieres #4 292 Albani Albani - Lajeunesse, Marie Emma 313 Albani Portraits de Femmes 406 Albani Biographie d'Albani - Emma Lajeunesse 286 Albani, Madame Souvenirs et Biographies 1870-1910 098 Albert Our French Canadian Ancestors Vol. 18 117 Albert Nos Ancetres Vol.18 066 Albro, Gideon New England Families - Genealogical and Memorial 088 Allain Our French Canadian Ancestors Vol. 9 108 Allain Nos Ancetres Vol.9 089 Allaire Our French Canadian Ancestors Vol. 10 109 Allaire Nos Ancetres Vol.10 031 Allard Les Anciennes Familles du Quebec 082 Allard Our French Canadian Ancestors Vol. -

CUHSLMCM M165.Pdf (932.2Kb)

Volume 25, Annual Meeting Issue October, 2004 2004 MCMLA Award Winners MCMLA 2004 Wrap-Up Sarah Kirby, Chair Lenora Kinzie 2004 MCMLA Awards Committee 2003-04 MCMLA Chair On behalf of the MCMLA 2004 Honors & Awards Thanks to all who worked so hard to make 2004 a Committee, I would like to announce the winners. great year! Lots of exciting changes have taken place All of the candidates are winners! It was a difficult and there is more to come. The idea for a special decision because all of the candidates are very annual meeting MCMLA EXPRESS is an excellent outstanding and very qualified. example of changes taking place. The new web redesign is another. Have you been online yet to Barbara McDowell Award Erica Lake check it out? Special thanks to the Publications Committee. Bernice M. Hetzner Award Lisa Traditi Outsta nding Achievement Award Peggy Mullaly-Quijas The following recap of my Kansas City Chair Report is a short review of the past year…actions, decisions, and future plans. The Business Meeting minutes with Erica Lake is the medical librarian at LDS additional details will be on the web page in the very Hospital in Salt Lake City, Utah. Erica has made a near future. major impact as a leader in her hospital system, Intermountain Health Care. She has been a Leadership Grant: Last November we applied for dynamic force in the evaluation and selection of MLA’s Leadership and Management Section grant to electronic databases with corporate-wide access. provide additional funding to support Dr. Michelynn Erica is very active in the local consortium, Utah McKnight’s CE presentation “Proving Your Worth” Health Sciences Library Consortium, and is at the annual meeting. -

Willa Cather Review

Copyright C 1997 by the Willa Cather Pioneer ISSN 0197-663X Memorial and Educational Foundation (The Willa Cather Society) Willa Cather Pioneer Memorial New-sletter and 326 N. Webster Street VOLUME XLI, No. 2 Red Cloud, Nebraska 68970 Summer/Fall, 1997 Review Telephone (402) 746-2653 The Little House and the Big Rock: So - what happened to me when I began to try to plan my paper for today was that my two projects Wilder, Cather, and refused to remain separate in my mind, and I had to the Problem of Frontier Girls envision a picture with a place for Willa Cather and Laura Ingalls Wilder. That meant I had to think about Plenary Address, new ways to historicize both careers. And that's why Sixth International Willa Cather Seminar I was so delighted to recognize the bit of information Quebec City, June 1995 with which I began. It places Wilder and Cather - Ann Romines who almost but not quite shared a publisher in 1931 - George Washington University in the same literary and cultural landscape. Women of about the same age with Midwestern childhoods far In August 1931, Alfred A. Knopf published Willa behind them, they were writing and publishing novels Cather's tenth novel, Shadows on the Rock. The publisher numbered Cather among the ''family" of authors he was proud to publish.1 Then, in the following month, Knopf contracted to publish the first book by a contemporary of Cather's, the children's novel Little House in the Big Woods by Laura Ingalls Wilder. Be fore the year was out, however, Wilder learned that the exigencies of "depression economics" were closing down the children's department at Knopf. -

2019 ALA Impact Report

FIND THE LIBRARY AT YOUR PLACE 2019 IMPACT REPORT THIS REPORT HIGHLIGHTS ALA’S 2019 FISCAL YEAR, which ended August 31, 2019. In order to provide an up-to-date picture of the Association, it also includes information on major initiatives and, where available, updated data through spring 2020. MISSION The mission of the American Library Association is to provide leadership for the development, promotion, and improvement of library and information services and the profession of librarianship in order to enhance learning and ensure access to information for all. MEMBERSHIP ALA has more than 58,000 members, including librarians, library workers, library trustees, and other interested people from every state and many nations. The Association services public, state, school, and academic libraries, as well as special libraries for people working in government, commerce and industry, the arts, and the armed services, or in hospitals, prisons, and other institutions. Dear Colleagues and Friends, 2019 brought the seeds of change to the American Library Association as it looked for new headquarters, searched for an executive director, and deeply examined how it can better serve its members and the public. We are excited to give you a glimpse into this momentous year for ALA as we continue to work at being a leading voice for information access, equity and inclusion, and social justice within the profession and in the broader world. In this Impact Report, you will find highlights from 2019, including updates on activities related to ALA’s Strategic Directions: • Advocacy • Information Policy • Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion • Professional & Leadership Development We are excited to share stories about our national campaigns and conferences, the expansion of our digital footprint, and the success of our work to #FundLibraries. -

Becoming a Superior in the Congre´Gation De Notre-Dame of Montreal, 1693–1796

Power, Position and the pesante charge: Becoming a Superior in the Congre´gation de Notre-Dame of Montreal, 1693–1796 COLLEEN GRAY* Research surrounding convents in mediaeval Europe, post-Tridentine Latin America, and eighteenth-century Canada has argued that well-born religious women achieved top administrative positions within their respective institutions pri- marily due to their social and financial connections. This study of the Congre´gation de Notre-Dame in Montreal between 1693 and 1796, however, reveals that ordinary individuals were at the helm as superiors of this particular institution, and that they achieved this position largely as a result of their own demonstrated talents. This interpretation broadens the notion of an ancien re´gime in which wealth, patronage, and connections ruled the day to include the possibility that an individual’s abilities were also important. The study also demonstrates the persistent efficacy of empirical social history, when used in combination with other methodologies, in historical analysis. Les recherches sur les couvents de l’Europe me´die´vale, de l’Ame´rique latine post- tridentine et du Canada du XVIIIe sie`cle donnaient a` penser que les religieuses de bonne naissance obtenaient des postes supe´rieurs dans l’administration de leurs e´tablissements respectifs en raison surtout de leurs relations sociales et financie`res. Cette e´tude de la Congre´gation de Notre-Dame de Montre´al entre 1693 et 1796 re´ve`le toutefois que des femmes ordinaires ont e´te´ me`re supe´rieure de cet e´tablissement particulier et qu’elles acce´daient a` ce poste graˆce en bonne * Colleen Gray is adjunct professor in the Department of History at Queen’s University. -

Portugal O Auberge AV

ARRONDISSEMENT DE VILLE-MARIE Prairies Rivière des Rivière-des-Prairies– Pointe-aux-Trembles– L’Île-Bizard– Montréal-Est 1 23456 Sainte-Geneviève– RU S AV. DE Montréal-Nord RUE CUVILLIER P Pierrefonds– LAURENDEAURUE ANDRÉ- Vidéographe inc. E C RUE POITEVIN Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue R Théâtre RUE DAVIDSON I o N Caserne n 26 RUE HUTCHISON Senneville Centre La Licorne HABOT A A École Saint- Jardincommunautaire Parc-école G RUE WILLIAM- V AV. MC NIDER AV. NELSON V . RUE DE MENTANA le beau voyage TREMBLAY G . M Enfant-Jésus Rivard Saint-Émile R A D C R VILLE O IEN P H E B RUE SAINT-HUBERT Anjou L O UE D V E . Conservatoire d’art R -ROYAL W RUE CLARK F RUE PONTIAC T RUE SAINT-DOMINIQUE E N UL. MO D IL Parc BO O AV. COLONIALE dramatique de Montréal E Théâtre du RUE RESTHER O E G Albert- RUE GÉNÉREUX L BOUL. SAINT-LAURENT D A E VILLENEUV Conservatoire de E Rideau-Vert Saint-Martin RU RUE SAINT-URBAIN U RUE LAFRANCE Parc des RUE DE BORDEAUX C R TSSE GUINDON Ô musique de Montréal AV. DE L'ESPLANADE ET RUE DE BULLION Compagnons- R T RUE JEANNE-MANCE Parc Pierre- AV. DU MONT-ROYAL École t O E Jardin communautaire Pierrefonds– Saint-Léonard n F - AV. AV. DU PARC École nationale Boucher, de-Saint-Laurent e A S AV. PAPINEAU Préfontaine Saint-Émile r L RUE CARTIER E A acteur u d’administration Bibliothèque et RUE DE LANAUDIÈRE Senneville D I RUE SIMARD a . N RU H V. -

Evelyn I. Funda

Evelyn I. Funda College of Humanities and Social Sciences [email protected] Utah State University (435) 797-3653 (office) 0700 Old Main Hill (435) 760-9703 (cell) Logan, UT 84322-0700 EDUCATION: Ph.D, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, 1994. (American Literature, Secondary Areas: Western American Literature and Folklore. Language: Czech) M.A., Boise State University, 1986 (English Education) B.A., Boise State University, 1984 English (Secondary Ed. emphasis / History minor) PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS: Associate Dean of Graduate Studies, College of Humanities & Social Sciences, 2016-Present Director, Mountain West Center for Regional Studies (CHaSS) 2016-Present Professor of English, Utah State University 2015-Present (Specializing in Willa Cather, American Literature 1865-1945, Western American memoir, and Agrarian Literature and Culture) Acting Department Head, English (February-March) 2020 Associate Professor of English, Utah State University 2001-2015 Assistant Professor of English, Utah State University 1995-2001 Instructor & Graduate Teaching Assistant, University of Nebraska-Lincoln 1989-1995 English Teacher, Kofa High School, Yuma, Arizona 1986-1989 PUBLICATIONS: Book (Peer-Reviewed): Weeds: A Farm Daughter’s Lament. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2013. • Reviewed in The New York Times Sunday Supplement, Prairie Schooner, Shelf Awareness, Midwest Book Review, Kirkus, Booklist, Western American Literature, ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, Pacific Northwest Quarterly, Lifewriting Annual, Kosmos: Czechoslovak and Central European Journal. • Winner of Evans Handcart Award for Biography, 2014. Textbook: Farm: A Multimodal Reader. 3rd Edition. (Forthcoming). Textbook co-authored and edited with Joyce Kinkead and Lynne McNeill. Logan: Utah State University Press, 2020. (Two previous editions published by Fountainhead Press, 2014 and 2016). -

Willa Cather Pioneer Memorial Newsletter VOLUME XXXV, No

Copyright © 1992 by the Wills Cather Pioneer ISSN 0197-663X Memorial and.Educational Foundation Winter, 1991-92 Willa Cather Pioneer Memorial Newsletter VOLUME XXXV, No. 4 Bibliographical Issue RED CLOUD, NEBRASKA Jim Farmer’s photo of the Hanover Bank and Trust in Johnstown, Nebraska, communicates the ambience of the historic town serving as winter locale for the Hallmark Hall of Fame/Lorimar version of O Pioneers.l, starring Jessica Lange. The CBS telecast is scheduled for Sunday 2 February at 8:00 p.m. |CST). A special screening of this Craig Anderson production previewed in Red Cloud on 18 January with Mr. Anderson as special guest. Board News Works on Cather 1990-1991" A Bibliographical Essay THE WCPM BOARD OF GOVERNORS VOTED UNANIMOUSLY AT THE ANNUAL SEPTEMBER Virgil Albertini MEETING TO ACCEPT THE RED CLOUD OPERA Northwest Missouri State University HOUSE AS A GIFT FROM OWNER FRANK MOR- The outpouring of criticism and scholarship on HART OF HASTINGS, NEBRASKA. The Board ac- Willa Cather definitely continues and shows signs of cepted this gift with the intention of restoring the increasing each year. In 1989-1990, fifty-four second floor auditorium to its former condition and articles, including the first six discussed below, and the significance it enjoyed in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Among the actresses who appeared on five books were devoted to Cather. In 1990-91, the its stage was Miss Willa Cather, who starred here as number increased to sixty-five articles, including the Merchant Father in a production of Beauty and those in four collections, and eight books. -

Recensement De 1666 À Montréal

Recensement de Montréal de 1666 Depuis sa fondation en 1642, la population de la ville de Montréal est passée à 627 habitants en 24 ans (1666). En parcourant ce recensement, vous trouverez probablement vos ancêtres. Philibert Couillaud n'y figure pas mais son épouse Catherine Laporte y est en page 5. Elle n’a que deux ans. L'orthographe des prénoms et noms est telle qu'elle apparaissait à l'époque. Montreal Census of 1666 24 years after it's foundation the population of Montreal was counting 627 inhabitants in 1666. Reading this document carefully, you will most likely find many of your ancestors. Philibert Couillauds name doesn't appear on the census but his wifes name is on page 5. Catherine Laporte is 2 years old then. For those whose french is not so good there is a translation at the end. FAMILLES des HABITTANTS ÂGE QUALLITEZ et MESTIERS Louis Artus Escuyer, Sieur de Sailly 40 Juge de la Court Royale Anne Françoise Bourdezau 28 Son Épouse Marie Angélique Artus 6 Fille Suzanne Artus 3 Fille Marie Artus 6 mois Fille Adrien Canillon 21 Homme laboureur,engagé Pierre Poupardeau 22 Domestique,engagé Charles Le Moyne 42 Procureur du Roy Catherine Primo Demoiselle 25 Son épouse Charles Le Moyne 9 Fils Jacques Le Moyne 7 Fils Pierre Le Moyne 4 Fils (Pierre sera mieux connu sous le nom d'Iberville) Paul le Moyne 3 Fils Joachim Brunet 20 Domestique,engagé Dezir Vigier 22 Marin,domestique engagé Simon Guillory 20 Arquebusier,domestique,engagé Adrien St-Aubin 18 Domestique,engagé Catherine Moytié 16 Domestique Jean Baptiste Migeon, Sieur Commis -

Guide to Spiritual and Religious Journeys in Québec

Guide to Guide Spiritual and Religious Journeys and Religious Spiritual his one-of-a-kind guidebook is an invitation to discover a panoply T of spiritual and sacred places in every region of Québec. Its 15 inspirational tours and magnificent photos reveal an exceptionally rich heritage unequalled anywhere else in North America. The Guide to Spiritual and Religious Journeys in Québec will delight pilgrims whose journeys are prompted by their faith as well as those in Québec drawn by art, architecture, and history. The tours offer unique spiritual experiences while exploring countless sacred places: shrines, basilicas, museums, churches, cemeteries, ways of the cross, and temples of a variety of faiths. You’ll also meet remarkable individuals and communities, and enjoy contemplation and reflection while communing with nature. ISBN : 978-2-76582-678-1 (version numérique) www.ulyssesguides.com Guide to Spiritual and Religious Journeys in Québec Research and Writing: Siham Jamaa Photo Credits Translation: Elke Love, Matthew McLauchlin, Christine Poulin, Tanya Solari, John Sweet Cover Page Forest trail © iStockphoto.com/Nikada; Saint Editors: Pierre Ledoux and Claude Morneau Joseph’s Oratory of Mount Royal © iStockphoto. com/AK2; Notre-Dame de Québec Basilica- Copy Editing: Elke Love, Matthew McLauchlin Cathedral © Daniel Abel-photographe; Our Lady Editing Assistant: Ambroise Gabriel of the Cape Shrine gardens © Michel Julien; Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré Shrine © Sainte-Anne- Graphic Design and Layout: Pascal Biet de-Beaupré Shrine; Ermitage Saint-Antoine de Lac-Bouchette © Ermitage Saint-Antoine de This work was produced under the direction of Olivier Gougeon and Claude Morneau. Lac-Bouchette Back Cover Abbaye de Saint-Benoît-du-Lac © iStockphoto. -

Pour Assurer Un Avenir Au Passé. Des Lieux De Mémoire Communs Au

POUR ASSURER UN AVENIR AU PASSÉ Des lieux de mémoire communs au Québec et à la France COMMISSION FRANCO-QUÉBÉCOISE SUR LES LIEUX DE MÉMOIRE COMMUNS Ce recueil est publié par la Commission franco-québécoise sur les lieux de mémoire communs en collaboration avec le Service de la recherche et de l’évaluation du Musée de la civilisation et l’Association Québec-France. COLLABORATEURS Rédaction et révision des textes Membres du Comité de mise en valeur Coordination de la production Claude Paulette Recherche iconographique Swann Freslon Karim Souiah Infographie et conception de la page couverture Danielle Roy Données de catalogage avant publication (Canada) Commission franco-québécoise sur les lieux de mémoire communs. Des lieux de mémoire communs au Québec et à la France. Pour assurer un avenir au passé, Québec, Musée de la civilisation, septembre 2005, 108 p. Comprend des références bibliographiques ISBN : 2-550-44041-2 La Commission franco-québécoise sur les lieux de mémoire communs est subventionnée par le ministère de la Culture et des Communications, par le ministère des Relations internationales du Québec ainsi que par le Consulat général de France. Illustrations de la page couverture : Les meubles de Mgr de Saint-Vallier à l’Hôpital général de Québec, J. Jaillet, photographe. Le Palais de l’Intendant, ANC. La chapelle Notre-Dame-du-Bonsecours, Commission des monuments historiques de la Province de Québec. Illustration du couvert 4 : Le fort et le moulin de Senneville, BMQ. Avant-propos 3 Aujourd’hui, la notion de « lieu de mémoire » est entrée dans le langage courant ; elle fait partie des préoccupations majeures de la population.