Convocation for New Students (2000 Program)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

If the Hat Fits, Wear It!

If the hat fits, wear it! By Canon Jim Foley Before I put pen to paper let me declare my interests. My grandfather, Michael Foley, was a silk hatter in one of the many small artisan businesses in Claythorn Street that were so characteristic of the Calton district of Glasgow in late Victorian times. Hence my genetic interest in hats of any kind, from top hats that kept you at a safe distance, to fascinators that would knock your eye out if you got too close. There are hats and hats. Beaver: more of a hat than an animal As students for the priesthood in Rome the wearing of a ‘beaver’ was an obligatory part of clerical dress. Later, as young priests we were required, by decree of the Glasgow Synod, to wear a hat when out and about our parishes. But then, so did most respectable citizens. A hat could alert you to the social standing of a citizen at a distance of a hundred yards. The earliest ‘top’ hats, known colloquially as ‘lum’ hats, signalled the approach of a doctor, a priest or an undertaker, often in that order. With the invention of the combustion engine and the tram, lum hats had to be shortened, unless the wearer could be persuaded to sit in the upper deck exposed to the elements with the risk of losing the hat all together. I understand that the process of shortening these hats by a few inches led to a brief revival of the style and of the Foley family fortunes, but not for long. -

An Argument for the Wider Adoption and Use of Traditional Academic Attire Within Roman Catholic Church Services

Transactions of the Burgon Society Volume 17 Article 7 10-21-2018 An Argument for the Wider Adoption and Use of Traditional Academic Attire within Roman Catholic Church Services Seamus Addison Hargrave [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/burgonsociety Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Higher Education Commons, History of Christianity Commons, and the Religious Education Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License Recommended Citation Hargrave, Seamus Addison (2018) "An Argument for the Wider Adoption and Use of Traditional Academic Attire within Roman Catholic Church Services," Transactions of the Burgon Society: Vol. 17. https://doi.org/10.4148/2475-7799.1150 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Transactions of the Burgon Society by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Transactions of the Burgon Society, 17 (2017), pages 101–122 An Argument for the Wider Adoption and Use of Traditional Academic Attire within Roman Catholic Church Services By Seamus Addison Hargrave Introduction It has often been remarked that whilst attending Church of England or Church of Scotland services there is frequently a rich and widely used pageantry of academic regalia to be seen amongst the ministers, whilst among the Catholic counterparts there seems an almost near wilful ignorance of these meaningful articles. The response often returned when raising this issue with various members of the Catholic clergy is: ‘well, that would be a Protestant prac- tice.’ This apparent association of academic dress with the Protestant denominations seems to have led to the total abandonment of academic dress amongst the clergy and laity of the Catholic Church. -

What They Wear the Observer | FEBRUARY 2020 | 1 in the Habit

SPECIAL SECTION FEBRUARY 2020 Inside Poor Clare Colettines ....... 2 Benedictines of Marmion Abbey What .............................. 4 Everyday Wear for Priests ......... 6 Priests’ Vestments ...... 8 Deacons’ Attire .......................... 10 Monsignors’ They Attire .............. 12 Bishops’ Attire ........................... 14 — Text and photos by Amanda Hudson, news editor; design by Sharon Boehlefeld, features editor Wear Learn the names of the everyday and liturgical attire worn by bishops, monsignors, priests, deacons and religious in the Rockford Diocese. And learn what each piece of clothing means in the lives of those who have given themselves to the service of God. What They Wear The Observer | FEBRUARY 2020 | 1 In the Habit Mother Habits Span Centuries Dominica Stein, PCC he wearing n The hood — of habits in humility; religious com- n The belt — purity; munities goes and Tback to the early 300s. n The scapular — The Armenian manual labor. monks founded by For women, a veil Eustatius in 318 was part of the habit, were the first to originating from the have their entire rite of consecrated community virgins as a bride of dress alike. Belt placement Christ. Using a veil was Having “the members an adaptation of the societal practice (dress) the same,” says where married women covered their Mother Dominica Stein, hair when in public. Poor Clare Colettines, “was a Putting on the habit was an symbol of unity. The wearing of outward sign of profession in a the habit was a symbol of leaving religious order. Early on, those the secular life to give oneself to joining an order were clothed in the God.” order’s habit almost immediately. -

How Do Cardinals Choose Which Hat to Wear?

How Do Cardinals Choose Which Hat to Wear? By Forrest Wickman March 12, 2013 6:30 PM A cardinal adjusts his mitre cap. Photo by Alessia Pierdomenico/Reuters One-hundred-fifteen Roman Catholic cardinals locked themselves up in the Vatican today to select the church’s next pope. In pictures of the cardinals, they were shown wearing a variety of unusual hats. How do cardinals choose their hats? To suit the occasion, to represent their homeland, or, sometimes, to make a personal statement. Cardinals primarily wear one of three different types. The most basic hat is a skullcap called the zucchetto (pl. zucchetti), which is a simple round hat that looks like a beanie or yarmulke. Next is the collapsible biretta, a taller, square-ridged cap with three peaks on top. There are certain times when it’s customary to put on the biretta, such as when entering and leaving church for Mass, but it’s often just personal preference. Cardinals wear both of these hats in red, which symbolizes how each cardinal should be willing to spill his blood for the church. (The zucchetto is actually worn beneath the biretta.) Some cardinals also wear regional variations on the hat, such as the Spanish style, which features four peaks instead of three. On special occasions, such as when preparing to elect the next leader of their church, they may also wear a mitre, which is a tall and usually white pointed hat. The mitre is the same style of cap commonly worn by the pope, and it comes in three different styles with varying degrees of ornamentation, according to the occasion. -

Faith Formation Resource to Welcome Cardinal Joseph W. Tobin As the Sixth Archbishop of Newark

1 Faith Formation Resource to Welcome Cardinal Joseph W. Tobin as the Sixth Archbishop of Newark This catechetical tool is available for use throughout the Archdiocese of Newark to provide resources for catechists to seize this teachable and historical moment. The objectives are listed by grade level and were taken from the Catechetical Curriculum Guidelines for the Archdiocese of Newark. Let us keep our new Archbishop in prayer. Kindergarten Focus - Many Signs of God’s Love Scripture – Genesis 1:31 – God looked at everything He had made, and found it very good. Objective: To help children grow in their understanding of the People of God as God’s family and as a sign of God’s love. Some ideas: o Share pictures of your parish pastor, Cardinal Tobin, and Pope Francis; Explain that they each serve God and our Catholic family in a special way, and Cardinal Tobin is now serving God in a special way as our new Archbishop. o Point out the Scarlet red color as a sign of being a Cardinal o Use the Cardinal and Pope Craft for Catholic Kids activity o Pray for Cardinal Tobin and the Archdiocese of Newark. For discussion: o Does God love us very much? (Yes) o How much does God love us? (Spread your arms wide to show how big God’s love is) o Because God loves us, He sends us good people to lead us in our Church, like Cardinal Tobin, our new Archbishop. o Let’s pray for Cardinal Tobin, and give thanks to God for His love. -

The St. Francis Bulletin

St. Francis Anglican Church January 2019 Volume 26, Issue 1 THE ST. FRANCIS BULLETIN FROM THE RECTOR Fr. Len Giacolone First of all, please accept my sincere wish that your While it is several months away, Bishop Iker is new year will be happy, prosperous and above all holy. scheduled to have his annual visitation of the parish If you spent any time in Advent trying to come closer on June 23 of this year. At that time he usually administers the Sacrament of Confirmation to those to the Lord, make your first resolution for the new year who are presented to him by the Rector. Since this to continue that journey each and every day. No one requires some preparation on the part of those to be who does that ever has any regrets. confirmed, I need to know very soon if you wish to be confirmed by the bishop when he comes. I am aware January is the month when we always have our that there are some of our members in this category annual parish meeting. This year’s meeting will take but I will still need to be contacted by anyone who place on Sunday, January 20 at 12:30 pm. The meeting wishes to be confirmed so that I can set up times for always features several reports including one each instructions prior to the bishop’s visitation. from the Rector, Senior Warden, and Treasurer. Also, During the last week in January, the clergy of the as you know, there will be an election for three new diocese will make their annual retreat at Montserrat Vestry members to replace members whose terms Jesuit Retreat House in Lewisville, Texas. -

Make-Up Lesson for Sunday Session 4-A for Grade 1 March - April Our Lady of Lourdes Roman Catholic Church Erath, Louisiana

Make-up Lesson for Sunday Session 4-a for Grade 1 March - April Our Lady of Lourdes Roman Catholic Church Erath, Louisiana Large-Group Assembly for Grades 1 and 2 After Opening Prayer, Mrs. Frances greeted the children and quickly reviewed a couple of facts regarding the liturgical calendar (Seasons of Lent and Easter). When time permits, she often shares pictures from our most recent Saint Joseph Altar (usually held on March 18-19) in our church parish hall. o See pictures of our Saint Joseph Altar. o Read a brochure about the Saint Joseph Altar. Show and Tell: Sacred Vessels used to Celebrate Mass After Grade 2 students went into their classrooms, Grade 1 students remained in a large-group assembly with Mrs. Frances. The plates, cups, napkins, and other objects used to celebrate the Mass are much too sacred (holy) (and often too expensive) to bring them into the classroom to play a church version of “Show and Tell.” Borrowing an idea from social media, Mrs. Frances purchased, repurposed, and spray painted several everyday kitchen items so she could discuss the names and uses for the sacred vessels priests use when they celebrate Mass. Card Games to introduce/review Sacred Vessels and Other Common Elements Found in Catholic Churches A few years ago, in a “light bulb moment” a couple of days before one of our elementary classes, Mrs. Frances quickly drew 64 “rough draft” sketches of sacred objects (and other common elements found in Catholic Churches) used before, during, and/or after the Liturgy of the Mass. -

Volume 3 Issue 10 Class of 2018 1-4 Why the Cap and Gown? Ren Dutton Student Life 5-6 the Cap and Gown Is an Iconic Symbol of Graduation

THE DAILY Volume 3 Issue 10 Class of 2018 1-4 Why the Cap and Gown? Ren Dutton Student Life 5-6 The cap and gown is an iconic symbol of graduation. Hey Mr. Tiger 7 We all wear them, but we don’t put much thought into why. It all started in the early universities in Europe during the Letter from Jody 8 twelfth thirteenth centuries. Scholars started wearing long hooded robes to stay warm. Since the robes were hooded they didn’t wear the caps. This robe eventually evolved into the Gown which was actually called an academic dress. The hat that was worn was called a biretta, which evolved into the cap. The top of the cap is shaped like a square. This is the same shape as a mortarboard. A mortarboard is a small square of wood or metal used for holding mortar. This sym- bolizes superiority and intelligence, and that graduates are building and moving on with their life. It also shows that they are master workmen. The schools didn’t want to have their students wearing excessive apparel, so they had all the stu- dents wear a gown as a sign of unity. Now, as we are walking down the aisle on graduation day and wondering why we are dressed in funny clothes, there will be a reason and you will know it we can be knowlegable of the reason why. 1 1 Class of 2018 It’s The Memories That Count, Not The Senior Pranks Ceanna Jones Thoughts Seniors, it’s the time of year when things are winding Adison Ellsworth down and you are running out of time. -

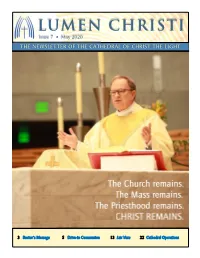

LUMEN CHRISTI Issue 7 • May 2020 the NEWSLETTER of the CATHEDRAL of CHRIST the LIGHT

LUMEN CHRISTI Issue 7 • May 2020 THE NEWSLETTER OF THE CATHEDRAL OF CHRIST THE LIGHT 3 Rector’s Message 5 Drive-in Communion 13 Lux Vera 22 Cathedral Operations In This Issue 3 Rector’s 19 Help the Message Cathedral ...and more! 5 From the 22 Cathedral Communications Operations Manager 7 Guide to Drive- in Holy Communion 15 Lux Vera 15 13 St. John Nepomuk 6 15 Ascension 16 Mexican Martyrs 18 Pentecost 2 From the Cathedral Rector As of the publication of this Lumen Christi newsletter, the State of California has extended the shelter-in-place order through the month of May. We are once again faced with the prospect of no public Masses until then. This means that most Catholics in California may go the entire Easter Season without receiving the Holy Eucharist. As a priest, this is a painful and difficult reality that requires us to rethink how we minister to the faithful in this time of crisis. We are realizing more and more that livestreamed Masses are not enough—the people want the Lord Himself! After much discussion and much more prayer, the Cathedral Staff and I have decided to undertake a bold, creative, yet prudent and safe way to minister to the people who hunger for Christ so much. On Sunday, May 10 (Mother’s Day) and Sunday, May 17 (Sixth Sunday of Easter), we will be offering Holy Communion to all those who come to the Cathedral Parking Garage between 9:30 AM and 10:45 AM. Simply drive with your families into the Garage through the 21st Street entrance, going straight toward the exit. -

STALL of ST PATRICK At

THE ANGLICAN CHURCH IN THE DIOCESE OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO HOLY EUCHARIST AND INSTALLATION OF THE REVEREND ERWIN TEMBO, M.A. to the STALL OF ST PATRICK at THE CATHERDAL CHURCH OF THE HOLY TRINITY, PORT OF SPAIN on Friday October 18, 2019 AT 6:00 PM (The Feast of St. Luke) at Frank De Freitas Printing & Binding THE CAHERDAL CHURCH OF THE HOLY TRINITY 28 Pelham St., Belmont, Trinidad W.I. Tel.: (868) 623-7169, (868) 229-6453 30A ABERCROMBY STREET, PORT OF SPAIN. ORDER OF PROCESSION Thurifer and Boat Boy/Girl Crucifer Acolytes Diocesan Lay Ministers Visiting Clergy Diocesan Clergy Church Wardens Mace Bearer New Canon Dean's Verger bearing Verge The Cathedral Chapter The Dean the Registrar The Chancellor A Server Retired Bishop A Server Retired Bishop A Server Retried Bishop A Server The Bishop's Chaplain The Bishop 1 AT THE EUCHARIST Celebrant: The Rt. Rev. Claude Berkley, Diocesan Bishop Concelebrants: Archdeacons Kenley Baldeo, Philip Isaac and Edwin Primus; Archdeacon Emeritus Steve West; Canons Colin Sampson, Richard Jacob, and Erwin Tembo; Canon Emeritus Hilton Bonas and Dean Dr. Shelley-Ann Tenia Preacher: The Venerable Kenley Baldeo, Archdeacon North and Rector of the Parish of Good Shepherd Deacon of the Mass: The Reverend Gerald Hendrickson, Deacon, Holy Trinity Cathedral M.C.: The Rev. Canon Richard Jacob, St. Chad’s Stall and Rector of the Parish of All Saints Assistant M.C.: The Reverend Dr. Eric Thompson, Priest in Charge, The Parish of St. Thomas, Chaguanas Servers: Cathedral and North East Region Lectors: Joy Douglas, People’s Warden, The Parish of St. -

Class Notes Spring04.4

Fall 2019/Winter 2020 Class NNootteess IN THIS ISSUE . See page 27 Faculty News (left to right – first row) Fr. Phillip J. Brown, P.S.S., Most Rev. William E. Lori, Fr. Gladstone Stevens, P.S.S. (left to right – second row) Dr. Michael J. Gorman (commencement speaker), Fr. Daniel Moore, P.S.S., Dr. Brent Laytham Fr. Phillip J. Brown, P.S.S. published the arti - Supreme Court Historical Society, the Board of Trustees of the cle: “Who Owns the Church” in a festschrift Thomas More Society of Maryland, and as Religious Assistant to for Rev. Robert Kaslyn, late Dean of the School the Society of Our Lady of the Most Holy Trinity. On a monthly of Canon Law of the Catholic University of basis Fr. Brown continues to serve as Chaplain to Teams of Our America. Fr. Brown represented St. Mary’s at Lady and continues to travel to dioceses for recruitment visits. the National Association of Catholic Theological Schools meeting in Chicago, On November 2, 2019, Fr. Dennis Billy, October 4-5, and the Annual Award Reception C.Ss.R. was a keynote speaker at the Diocese of the Catholic Mobilizing Network at the Apostolic Nunciature of Tucson, Arizona’s 6th Annual Men’s in Washington, DC, October 10. He attended the Annual Conference. The title of his presentation was, Awards Reception of St. Luke’s Institute at the Apostolic “Fully Alive! Living in the Wounds of the Nunciature in Washington, DC on October 21 and was invested Risen Lord—Our Growing Band of Brothers.” as Chaplain of the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of On December 4, 2019 he delivered the 45th Jerusalem on October 26, 2019. -

Church Vocabulary Liturgical Objects and Sacred Vessels Amphora

Church Vocabulary Liturgical Objects and Sacred Vessels Amphora: (Greek: amphi, both sides; phero, to carry) A wine vessel for Mass; tall, two- handled, often pottery (Symbolically inscribed one were found in the Catacombs.) Ampulla: Two-handed vessels for holding oils or burial ointments. Aspergillum: An instrument (brush or branch or perforated container) for sprinkling holy water. Aspersory: The pail for holy water Boat: The supply container for the incense. Capsula: The container for reserving the consecrated host for exposition in the monstrance. Censer: A vessel for burning incense (mixture of aromatic gums) at solemn ceremonies. Its rising smoke symbolizes prayers. Chalice: A cup that holds the wine (grape, “fruit of the vine”). Formerly of precious metals (if not gold, gold plated inside). Since Vatican II it must at least be a non-porous material of suitable dignity. Consecrated with holy chrism by a bishop; also “consecrated by use” (contact with Christ’s blood). Eight inches was the traditional and common height. Christ’s Last Supper chalice is the centerpiece if the medieval Holy Grail legends. Chalice veil: (no longer in common use) Covers the chalice and paten from the beginning of Mass until the offertory and after the ablutions. Ciborium: Container for the communion host; similar to a paten and traditionally resembling the chalice except for its cover. Communion plate: This was a plate made of a precious metal which would placed under the mouth or hands of the person receiving communion lest the Precious Body fall to the floor. Corporal: A square of linen cloth placed upon the altar and upon which the chalice and paten are placed (Its container, when the corporal is not in use, it called the Burse.