A Case Study Inquiry of Four Multi-Campus Colleges in New South Wales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 MANSW Annual Conference

2017 yenMANSW Annual Conference Adjusting Your Altitude PLATINUM SPONSORS MANSW thanks the following sponsors for their support of the 2017 MANSW Annual Conference GOLD SPONSOR SILVER SPONSORS OTHER SPONSORS Pre-Dinner Drinks President’s Reception Sponsor Presenter Gifts Welcome to the 2017 MANSW Annual Conference Adjusting Your Altitude 2017 MANSW Annual Conference Adjusting Your Altitude A very warm welcome to the 2017 MANSW Annual Conference: “Adjusting Your Altitude”. In deciding to bring the MANSW Annual Conference to the Blue Mountains this year, I wanted our theme to be related to the mountains in some way. In particular, the graphic that we have used this year stood out to me as a graphic that epitomises our work as teachers. To teach effectively, it is not enough to explain our knowledge, experiences, to talk students through the journey they will go on, all the potholes they may fall in, how to navigate, how to plan for bad weather, how to move up the mountain… you have to walk it with them, and help them on the way, adjusting as you go. We are excited to be able to welcome many educators to our conference this year, and there are many notable events to look forward to. On Friday morning we have two excellent speakers: Mark Harrison and Angela D’Angelo. Mark Harrison has a background in Mathematics and Psychology and will speak to us about Growth Mindset, in particular how understanding student mindsets can deeply influence our effectiveness in the classroom. Angela D’Angelo, one of the recipients of a Premier’s Teaching Scholarship in 2016, will continue the conversation around Growth Mindset as well as discuss her journey over the last year. -

Student Wellbeing

Manly Campus Northern Beaches Secondary College Academic Excellence Personal Best Giving Back to the Community Principal: Ms Cath Whalan Deputy Principals: Ms Kathy O’Sullivan Mr Alex Newcomb 9 March 2018 – Newsletter No. 6 From the Principal School Discos Disco fever took over the school this week with Welcome to New Parents Year 12 adding their own fundraising disco on On Wednesday evening the P&C and Year 8 Tuesday night to the annual events for Year 7, 8 parents hosted an enjoyable social event to and 9 held on Wednesday and Thursday nights. welcome parents to our school community. The Once again the outstanding tech crew ensured the evening provided an opportunity for parents to sound and lighting effects created a wonderful meet other parents of their children’s new atmosphere for students to enjoy. classmates and also chat with the Year 8 parent Congratulations to the Year 12 SRC members who volunteers. It was wonderful to hear that students managed to coordinate and organise such a have transitioned smoothly to high school and are successful event in such a short time frame. enjoying the many different opportunities Manly Thank you to all those involved in making these has to offer. The Orientation week program, Year 7 events so successful, in particular to Ms Leviton for Camp and History incursion have been highlights guiding the tech crew, the teachers who helped for many students, allowing them to get to know with supervision and in the barbecue area, and the others in the year group whilst learning new skills. Year 10 peer support leaders who looked after We look forward to working closely with our Year 7 on Wednesday night. -

2019 Minister's and Secretary's Awards for Excellence Public Education Foundation 3 Award Recipients

We Give Life-Changing Scholarships 2019 Minister’s and Secretary’s Awards for Excellence MC Jane Caro Welcome Acknowledgement of Country Takesa Frank – Ulladulla High School Opening Remarks It’s my great pleasure to welcome you to the 2019 Minister’s David Hetherington and Secretary’s Awards for Excellence. These Awards showcase the wonderful people and extraordinary talent across NSW public education – schools, students, teachers, Minister’s Remarks employees and parents. The Hon Sarah Mitchell MLC Order of Proceedings Minister for Education and Early Childhood The Public Education Foundation’s mission is to celebrate the Learning best of public schooling, and these Awards are a highlight of our annual calendar. The Foundation is proud to host the Awards on behalf of The Honourable Sarah Mitchell MLC, Minister for Tuesday 27 August 2019 Presentations Education and Early Childhood Learning and Mr Mark Scott AO, 4-6pm Minister’s Award for Excellence in Secretary of the NSW Department of Education. Student Achievement Lower Town Hall, Minister’s Award for Excellence in Teaching You’ll hear today about outstanding achievements and breakthrough initiatives from across the state, from a new data Sydney Town Hall sharing system at Bankstown West Public School to a STEM Performance Industry School Partnership spanning three high schools across Listen With Your Heart regional NSW. Performed by Kyra Pollard Finigan School of Distance Education The Foundation recently celebrated our 10th birthday and to mark the occasion, we commissioned a survey of all our previous scholarship winners. We’re proud to report that over Secretary’s Remarks 98% of our eligible scholars have completed Year 12, and of Mark Scott AO these, 72% have progressed onto university. -

Selective High Schools Placement Test

Northern Beaches Secondary College Manly Campus Academic Excellence Personal Best Giving Back to the Community Principal: Ms Cath Whalan Deputy Principals: Ms Kathy O’Sullivan Mr Alex Newcomb 8 March 2019 – Newsletter No.4 From the Principal Careers Marketplace Year 12 Parent / Teacher Night The Year 10 and 12 Careers Marketplace held on The Year 12 Parent and Teacher evening was held last Thursday this week was once again a very successful night, providing a valuable opportunity for our staff to event. The feedback from students was very positive, meet with parents and discuss the progress of our 2019 indicating their appreciation of the invaluable HSC cohort. Students are encouraged to reflect on their opportunity to talk with industry professionals. The progress and the feedback provided by teachers to guest presenters, some of whom were ex-students of ensure they are working towards achieving their Manly, spoke glowingly about how engaged our personal best throughout the year. students were. Many thanks to Ms Colby and Ms Rixon for organising this excellent learning opportunity for our Year 7 Camp senior students. Our Year 7 students enjoyed the three day camp held last week at Mangrove Mountain. The wide variety of activities provided new experiences for our students to work together to solve problems and challenge themselves individually. Many thanks to Year Adviser Josinta Chandra for all her enthusiasm and organisation in ensuring the camp was so successful. Thanks also to the other staff including Ms Grace, Ms Rixon, Ms Woodward, Mr Nguyen, Mr Goykovic, Mr Forsyth and Mr Newcomb who gave their time to ensure our Year 7 students had such an enjoyable and worthwhile experience. -

YEAR in REVIEW 2018/19 Contents

YEAR IN REVIEW 2018/19 Contents 04 Chairman’s Message 05 CEO’s Message 06 Blacktown Venue Management Ltd 07 Blacktown Venue Management Ltd Board of Directors 08 Blacktown Key Venues 09 Blacktown Key Venues Management Staff 10 Health & Safety 12 Blacktown Football Park 15 Blacktown International Sportspark Sydney 16 AFL 19 Athletics 20 Baseball 22 Cricket 25 Football 27 Soft ball 28 Joe McAleer Oval 30 Blacktown Tennis Centre Stanhope 33 Blacktown Aquatic Centre 34 Blacktown Leisure Centre Stanhope 37 Charlie Lowles Leisure Centre Emerton 38 Mount Druitt Swimming Centre 40 Riverstone Swimming Centre Another fantastic year 43 Aqua Learn to Swim has passed with over 44 Looking forward 2.2 million visitors enjoying sport, leisure, 46 List of hirers recreation and fi tness outcomes across the 9 Key Venues facilities. 2 3 Chairman’s message As Chairman of Blacktown Venue Management Ltd., and on behalf of the Blacktown Venue Management Board of Directors it gives me great pleasure to welcome you to the 2018/19 Blacktown Key Venues year in review. I am honoured to take up the position as Chairman This commitment is demonstrated through the of Blacktown Venue Management Ltd (BVM). What endorsement by Blacktown City Council of the Blacktown an exciting time! We continue to make great progress International Sportspark Master plan. This Master towards delivery of our new state of the art International Plan will see the Sportspark at the forefront of sports Centre of Training Excellence (ICTE). The ICTE is a training and recovery through the inclusion of the ICTE Blacktown City transformational project that we are (International Centre of Training Excellence). -

10 2022 Administration Fee for Years 8 – 10

Applications Years 8 – 11, 2022 Applications open Monday 21 June 2021 and close Friday 16 July 2021 All enquiries: Please email [email protected] Years 8 – 10 2022 All students applying for Fort Street High School must include the following with their application. 1. Completed Selective Schools Application Form available on the Selective High School website: https://education.nsw.gov.au/public-schools/selective-high-schools-and-opportunity-classes/years-8-to- 12 2. English writing piece of maximum 600 words (handwritten – not typed): Year 8 – 10 2022 Essay Topic (if you are in Year 7,8 or 9 in 2021) “Something good can come out of a crisis. A crisis can bring about a real change and help us re- evaluate our humanity”. (Discuss) 3. A copy of the student’s Birth Certificate or Passport 4. A copy of the Semester 2 - 2020 school report and Semester 1 – 2021 school report (if available) 5. Copies of evidence of recent participation in academic competitions and co-curricular activities 6. All applications must be posted and received before, on or date stamped Friday 16 July 2021. Please do not come to the school. No emailed applications. No late applications will be considered. Postal Address: Fort Street High School – Enrolments, Parramatta Road Petersham NSW 2049 7. There is no entrance test for applicants for Years 8 – 10, 2022 Administration Fee for Years 8 – 10 Applications There is a $50 non-refundable administration fee to cover the processing of the application. Payment can be made by cheque made out to Fort Street High School (to be included with the application) or on our school website: www.fortstreet.nsw.edu.au 1. -

Schools Competition 2014 School Addresses and Contact Details

NSW Junior Chess League METROPOLITAN SECONDARY SCHOOLS COMPETITION 2014 SCHOOL ADDRESSES AND CONTACT DETAILS Abbotsleigh Region: Met North Address: 1666 Pacific Highway (cnr Ada Ave), Wahroonga NSW 2076 Chess Coordinator: Mr P Garside School Phone: 9473 7779 School Fax: 9473 7680 Ascham School Region: Met East Address: 188 New South Head Rd, Edgecliff NSW 2027 Chess Coordinator: Mr A Ferch School Phone: 8356 7000 School Fax: 8356 7230 Asquith Girls High School Region: Met North Address: Stokes Avenue, Asquith NSW 2077 Chess Coordinator: Mr M Borri School Phone: 9477 6411 School Fax: 9482 2524 Australian International Academy - Sydney Campus Region: Met East Address: 420 Liverpool Road, Strathfield NSW 2135 Chess Coordinator: Mr W Zoabi School Phone: 9642 0104 School Fax: 9642 0106 Balgowlah Boys (Northern Beaches Secondary College - Balgowlah Boys Campus) Region: Met North Address: Maretimo Street, Balgowlah NSW 2093 Chess Coordinator: Mr J Hu School Phone: 9949 4200 School Fax: 9907 0266 Barker College Region: Met North Address: 91 Pacific Highway, Hornsby NSW 2077 Chess Coordinator: Mrs G Cunningham School Phone: 9847 8399 School Fax: 9477 3556 Baulkham Hills High School Region: Met West Address: 419A Windsor Road, Baulkham Hills NSW 2153 Chess Coordinator: Mr J Chilwell School Phone: 9639 8699 School Fax: 9639 4999 Blue Mountains Grammar School Region: Met West Address: Matcham Avenue, Wentworth Falls NSW 2782 Chess Coordinator: Mr C Huxley School Phone: 4757 9000 School Fax: 4757 9092 Canterbury Boys High School Region: Met East Address: -

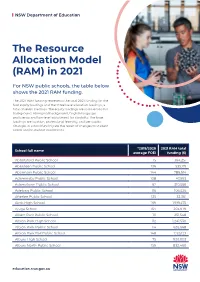

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 347,551 Alma Public -

Annual Report 2015 Harbord Financial Services Limited ABN 25 097 282 525 Freshwater Community Bank® Branch of Bendigo Bank Contents

[Type here] Annual report 2015 Harbord Financial Services Limited ABN 25 097 282 525 Freshwater Community Bank® Branch of Bendigo Bank Contents Chairman’s report 2 - 4 Manager’s report 5 Bendigo and Adelaide Bank Ltd Report 6 - 8 Directors’ report 9 – 14 Auditor’s Independence declaration 15 Financial Statements 16 – 19 Notes to the Financial Statements 20 – 41 Directors’ declaration 42 Independent Auditor’s report 43 – 44 Shareholder information 45 – 48 Director History 49 Sponsorship 2014/2015 50 - 52 Chairman’s report It is again a pleasure to report on the success of our great Bank and the strengthening of our Community Bank® network. With your support, excellent caring staff led by Sandy, a Board of Directors and Ambassadors who have to be the most balanced, qualified and motivated in the network, we have been able to contribute over $1,875,000 to this great community and over $550,000 in dividends to our local shareholders. These community grants and sponsorships have made a significant difference to a number of local organisations (all listed in the back of this annual report). We look forward to continuing to support these groups and others of course, as we grow with the community support! Review of Community Bank® model The review of the Community Bank® model, also known as Project Horizon, is a collaborative effort to rigorously explore and analyse the model; an approach strong underpinned by financial modelling and empirical analysis. The future model is being tested and reviewed through extensive consultation and enquiry. As a result of this our underlying margin share should increase from July 2016 and subsequently our profit. -

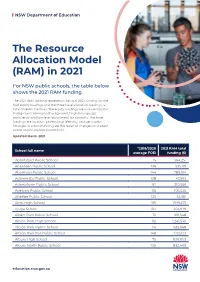

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. Updated March 2021 *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 -

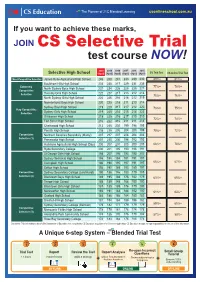

2020 Selective Trial Test Result

The Pioneer of 21C Blended Learning csonlineschool.com.au If you want to achieve these marks, JOIN CS Selective Trial test course NOW! 2020 2019 2018 2017 2016 2015 Selective High School (April) (April) (April) (April) (April) (April) CS Trial Test CS online Trial Test Most Competitive Selective James Ruse Agricultural High School 246 250 241 243 239 230 80%+ 81%+ Baulkham Hills High School 234 230 217 229 231 235 Extremely 77%+ 78%+ North Sydney Boys High School 231 234 226 225 225 221 Competitive Hornsby Girls High School 222 227 217 213 212 216 Selective 75%+ 76%+ North Sydney Girls High School 222 226 216 216 212 219 Normanhurst Boys High School 220 225 218 211 210 214 Sydney Boys High School 219 229 217 217 212 220 Very Competitive 73%+ 75%+ Sydney Girls High School 219 225 216 215 214 223 Selective Girraween High School 218 225 216 217 210 210 72%+ 74%+ Fort Street High School 216 222 215 211 211 216 Chatswood High School 213 215 202 199 198 198 Penrith High School 208 215 205 204 200 199 70%+ 72%+ Competitive Northern Beaches Secondary (Manly) 207 217 207 206 204 206 Selective (1) Parramatta High School 201 210 200 194 192 193 Hurlstone Agricultural High School (Day) 200 207 201 203 200 205 68%+ 70%+ Ryde Secondary College 200 201 195 190 186 191 St George Girls High School 198 207 195 195 195 202 Sydney Technical High School 198 198 194 191 191 197 Caringbah High School 196 198 195 197 191 197 65%+ 67%+ Sefton High School 192 197 189 193 189 197 Competitive Sydney Secondary College (Leichhardt) 190 186 186 183 179 185 Selective -

Northern Sydney District Data Profile Sydney, South Eastern Sydney, Northern Sydney Contents

Northern Sydney District Data Profile Sydney, South Eastern Sydney, Northern Sydney Contents Introduction 4 Demographic Data 7 Population – Northern Sydney 7 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population 10 Country of birth 12 Languages spoken at home 14 Migration Stream 17 Children and Young People 18 Government schools 18 Early childhood development 28 Vulnerable children and young people 34 Contact with child protection services 37 Economic Environment 38 Education 38 Employment 40 Income 41 Socio-economic advantage and disadvantage 43 Social Environment 45 Community safety and crime 45 2 Contents Maternal Health 50 Teenage pregnancy 50 Smoking during pregnancy 51 Australian Mothers Index 52 Disability 54 Need for assistance with core activities 54 Housing 55 Households 55 Tenure types 56 Housing affordability 57 Social housing 59 3 Contents Introduction This document presents a brief data profile for the Northern Sydney district. It contains a series of tables and graphs that show the characteristics of persons, families and communities. It includes demographic, housing, child development, community safety and child protection information. Where possible, we present this information at the local government area (LGA) level. In the Northern Sydney district there are nine LGAS: • Hornsby • Hunters Hill • Ku-ring-gai • Lane Cove • Mosman • North Sydney • Northern Beaches • Ryde • Willoughby The data presented in this document is from a number of different sources, including: • Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) • Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) • NSW Health Stats • Australian Early Developmental Census (AEDC) • NSW Government administrative data. 4 Northern Sydney District Data Profile The majority of these sources are publicly available. We have provided source statements for each table and graph.