TR-083 MYXOMYCETES SPECIES CONCEPTS-HAROLD KELLER.Cdr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myxomycetes NMW 2012Orange, Updated KS 2017.Docx

Myxomycete (Slime Mould) Collection Amgueddfa Cymru-National Museum Wales (NMW) Alan Orange (2012), updated by Katherine Slade (2017) Myxomycetes (true or plasmodial slime moulds) belong to the Eumycetozoa, within the Amoebozoa, a group of eukaryotes that are basal to a clade containing animals and fungi. Thus although they have traditionally been studied by mycologists they are distant from the true fungi. Arrangement & Nomenclature Slime Mould specimens in NMW are arranged in alphabetical order of the currently accepted name (as of 2012). Names used on specimen packets that are now synonyms are cross referenced in the list below. The collection currently contains 157 Myxomycete species. Specimens are mostly from Britain, with a few from other parts of Europe or from North America. The current standard work for identification of the British species is: Ing, B. 1999. The Myxomycetes of Britain and Ireland. An Identification Handbook. Slough: Richmond Publishing Co. Ltd. Nomenclature follows the online database of Slime Mould names at www.eumycetozoa.com (accessed 2012). This database is largely in line with Ing (1999). Preservation The feeding stage is a multinucleate motile mass known as a plasmodium. The fruiting stage is a dry, fungus-like structure containing abundant spores. Mature fruiting bodies of Myxomycetes can be collected and dried, and with few exceptions (such as Ceratiomyxa) they preserve well. Plasmodia cannot be preserved, but it is useful to record the colour if possible. Semi-mature fruiting bodies may continue to mature if collected with the substrate and kept in a cool moist chamber. Collected plasmodia are unlikely to fruit. Specimens are stored in boxes to prevent crushing; labels should not be allowed to touch the specimen. -

Slime Moulds

Queen’s University Biological Station Species List: Slime Molds The current list has been compiled by Richard Aaron, a naturalist and educator from Toronto, who has been running the Fabulous Fall Fungi workshop at QUBS between 2009 and 2019. Dr. Ivy Schoepf, QUBS Research Coordinator, edited the list in 2020 to include full taxonomy and information regarding species’ status using resources from The Natural Heritage Information Centre (April 2018) and The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (February 2018); iNaturalist and GBIF. Contact Ivy to report any errors, omissions and/or new sightings. Based on the aforementioned criteria we can expect to find a total of 33 species of slime molds (kingdom: Protozoa, phylum: Mycetozoa) present at QUBS. Species are Figure 1. One of the most commonly encountered reported using their full taxonomy; common slime mold at QUBS is the Dog Vomit Slime Mold (Fuligo septica). Slime molds are unique in the way name and status, based on whether the species is that they do not have cell walls. Unlike fungi, they of global or provincial concern (see Table 1 for also phagocytose their food before they digest it. details). All species are considered QUBS Photo courtesy of Mark Conboy. residents unless otherwise stated. Table 1. Status classification reported for the amphibians of QUBS. Global status based on IUCN Red List of Threatened Species rankings. Provincial status based on Ontario Natural Heritage Information Centre SRank. Global Status Provincial Status Extinct (EX) Presumed Extirpated (SX) Extinct in the -

Biodiversity of Plasmodial Slime Moulds (Myxogastria): Measurement and Interpretation

Protistology 1 (4), 161–178 (2000) Protistology August, 2000 Biodiversity of plasmodial slime moulds (Myxogastria): measurement and interpretation Yuri K. Novozhilova, Martin Schnittlerb, InnaV. Zemlianskaiac and Konstantin A. Fefelovd a V.L.Komarov Botanical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg, Russia, b Fairmont State College, Fairmont, West Virginia, U.S.A., c Volgograd Medical Academy, Department of Pharmacology and Botany, Volgograd, Russia, d Ural State University, Department of Botany, Yekaterinburg, Russia Summary For myxomycetes the understanding of their diversity and of their ecological function remains underdeveloped. Various problems in recording myxomycetes and analysis of their diversity are discussed by the examples taken from tundra, boreal, and arid areas of Russia and Kazakhstan. Recent advances in inventory of some regions of these areas are summarised. A rapid technique of moist chamber cultures can be used to obtain quantitative estimates of myxomycete species diversity and species abundance. Substrate sampling and species isolation by the moist chamber technique are indispensable for myxomycete inventory, measurement of species richness, and species abundance. General principles for the analysis of myxomycete diversity are discussed. Key words: slime moulds, Mycetozoa, Myxomycetes, biodiversity, ecology, distribu- tion, habitats Introduction decay (Madelin, 1984). The life cycle of myxomycetes includes two trophic stages: uninucleate myxoflagellates General patterns of community structure of terrestrial or amoebae, and a multi-nucleate plasmodium (Fig. 1). macro-organisms (plants, animals, and macrofungi) are The entire plasmodium turns almost all into fruit bodies, well known. Some mathematics methods are used for their called sporocarps (sporangia, aethalia, pseudoaethalia, or studying, from which the most popular are the quantita- plasmodiocarps). -

Slime Molds: Biology and Diversity

Glime, J. M. 2019. Slime Molds: Biology and Diversity. Chapt. 3-1. In: Glime, J. M. Bryophyte Ecology. Volume 2. Bryological 3-1-1 Interaction. Ebook sponsored by Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. Last updated 18 July 2020 and available at <https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology/>. CHAPTER 3-1 SLIME MOLDS: BIOLOGY AND DIVERSITY TABLE OF CONTENTS What are Slime Molds? ....................................................................................................................................... 3-1-2 Identification Difficulties ...................................................................................................................................... 3-1- Reproduction and Colonization ........................................................................................................................... 3-1-5 General Life Cycle ....................................................................................................................................... 3-1-6 Seasonal Changes ......................................................................................................................................... 3-1-7 Environmental Stimuli ............................................................................................................................... 3-1-13 Light .................................................................................................................................................... 3-1-13 pH and Volatile Substances -

Special Issue

OMPHALINA Special Issue ISSN 1925-1858 Newsletter of Sept 2019 • Vol X, No. 3 OMPHALINA, newsletter of Foray Newfoundland & Labrador, has no fi xed schedule of publication, and no promise to appear again. Its primary purpose is to serve as a conduit of information to registrants of the upcom- ing foray and secondarily as a communications tool with members. Issues of Omphalina are archived in: Board Directors C s ta s Library and Archives Canada’s Electronic Collection http://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/201/300/omphalina/index.html President Mycological Centre for Newfoundland Studies, Queen Elizabeth II Michael Burzynski Dave Malloch Library (printed copy also archived) Treasurer NB MUSEUM http://collections.mun.ca/cdm/search/collection/omphalina Geoff Th urlow Auditor Secretary Gordon Janes Th e content is neither discussed nor approved by the Robert McIsaac BONNELL COLE JANES Board of Directors. Th erefore, opinions expressed do Legal Counsel not represent the views of the Board, the Corporation, Directors the partners, the sponsors, or the members. Opinions Bill Bryden Andrew May are solely those of the authors and uncredited opinions Shawn Dawson BROTHERS & BURDEN solely those of the Editor. Rachelle Dove Webmaster Chris Deduke Jim Cornish Please address comments, complaints, and contributions Jamie Graham to the Editor, Sara Jenkins at [email protected] Anne Marceau Past President Helen Spencer Andrus Voitk Foray Newfoundland and Labrador is an Accepting C tr i s amateur, volunteer-run, community, not-for-profit We eagerly invite contributions to Omphalina, organization with a mission to organize enjoyable dealing with any aspect even remotely related to NL and informative amateur mushroom forays in mushrooms. -

The Mycetozoa of North America, Based Upon the Specimens in The

THE MYCETOZOA OF NORTH AMERICA HAGELSTEIN, MYCETOZOA PLATE 1 WOODLAND SCENES IZ THE MYCETOZOA OF NORTH AMERICA BASED UPON THE SPECIMENS IN THE HERBARIUM OF THE NEW YORK BOTANICAL GARDEN BY ROBERT HAGELSTEIN HONORARY CURATOR OF MYXOMYCETES ILLUSTRATED MINEOLA, NEW YORK PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR 1944 COPYRIGHT, 1944, BY ROBERT HAGELSTEIN LANCASTER PRESS, INC., LANCASTER, PA. PRINTED IN U. S. A. To (^My CJriend JOSEPH HENRI RISPAUD CONTENTS PAGES Preface 1-2 The Mycetozoa (introduction to life history) .... 3-6 Glossary 7-8 Classification with families and genera 9-12 Descriptions of genera and species 13-271 Conclusion 273-274 Literature cited or consulted 275-289 Index to genera and species 291-299 Explanation of plates 301-306 PLATES Plate 1 (frontispiece) facing title page 2 (colored) facing page 62 3 (colored) facing page 160 4 (colored) facing page 172 5 (colored) facing page 218 Plates 6-16 (half-tone) at end ^^^56^^^ f^^ PREFACE In the Herbarium of the New York Botanical Garden are the large private collections of Mycetozoa made by the late J. B. Ellis, and the late Dr. W. C. Sturgis. These include many speci- mens collected by the earlier American students, Bilgram, Farlow, Fullmer, Harkness, Harvey, Langlois, Macbride, Morgan, Peck, Ravenel, Rex, Thaxter, Wingate, and others. There is much type and authentic material. There are also several thousand specimens received from later collectors, and found in many parts of the world. During the past twenty years my associates and I have collected and studied in the field more than ten thousand developments in eastern North America. -

Arcyria Cinerea (Bull.) Pers

Myxomycete diversity of the Altay Mountains (southwestern Siberia, Russia) 1* 2 YURI K. NOVOZHILOV , MARTIN SCHNITTLER , 3 4 ANASTASIA V. VLASENKO & KONSTANTIN A. FEFELOV *[email protected] 1,3V.L. Komarov Botanical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences 197376 St. Petersburg, Russia, 2Institute of Botany and Landscape Ecology, Ernst-Moritz-Arndt University D-17487 Greifswald, Germany, 4Institute of Plant and Animal Ecology of the Russian Academy of Sciences Ural Division, 620144 Yekaterinburg, Russia Abstract ― A survey of 1488 records of myxomycetes found within a mountain taiga-dry steppe vegetation gradient has identified 161 species and 41 genera from the southeastern Altay mountains and adjacent territories of the high Ob’ river basin. Of these, 130 species were seen or collected in the field and 59 species were recorded from moist chamber cultures. Data analysis based on the species accumulation curve estimates that 75–83% of the total species richness has been recorded, among which 118 species are classified as rare (frequency < 0.5%) and 7 species as abundant (> 3% of all records). Among the 120 first species records for the Altay Mts. are 6 new records for Russia. The southeastern Altay taiga community assemblages appear highly similar to other taiga regions in Siberia but differ considerably from those documented from arid regions. The complete and comprehensive illustrated report is available at http://www.Mycotaxon.com/resources/weblists.html. Key words ― biodiversity, ecology, slime moulds Introduction Although we have a solid knowledge about the myxomycete diversity of coniferous boreal forests of the European part of Russia (Novozhilov 1980, 1999, Novozhilov & Fefelov 2001, Novozhilov & Lebedev 2006, Novozhilov & Schnittler 1997, Schnittler & Novozhilov 1996) the species associated with this vegetation type in Siberia are poorly studied. -

Europe, Sierra Physarales Are Pre- Lamproderma Will Be Presented. By

PERSOONIA Volume 18, Part 1, 71-84 (2002) A study of nivicolous Myxomycetes in southern Europe, Sierra de Guadarrama, Spain A. Sánchez G. Moreno C. Illana & H. Singer Eleven taxa of Myxomycetes collected from around melting snow banks in moun- tainous and alpine areas ofthe Sierra de Guadarrama (Madrid, Segovia) are pre- sented. From a chronological point of view several new records for the Iberian Peninsula are interesting: Lepidoderma carestianum,Lepidoderma granuliferum, Physarum albescens, Physarum alpestre and Trichia sordida var. sordida. SEM of and of the included. micrographs spores capillitia most significant species are Key words: nivicolous Myxomycetes, Physarales, Stemonitales, Trichiales, Spain, SEM, chronology, taxonomy. Introduction Nivicolous Myxomycetes have scarcely been studied in Spain. Gracia (1986), who cited three species in the Catalanian Pyrenees, made the first contribution.Later Lado (1992) and Illana et al. (1993) paid attentionto the Sierra de Guadarrama, from which they reported new records. mountain situatedin the centre of the The Sierra de Guadarrama is a range peninsula of the and Madrid. As last inves- forming part provinces Segovia our mycological tigations in these mountains yielded success, we were encouraged to study this area more exhaustively; especially the Segovian part of the mountains, where the autoch- thonous vegetation is better conserved. Stemonitales, Trichialesand In this paper, 11 taxa ofthe orders Physarales are pre- in sented. A second part will deal with nivicolous species ofthe genus Diderma and, the last work, the collection of nivicolousLamproderma will be presented. MATERIAL AND METHODS The investigated area, Sierra de Guadarrama, is part ofSpain, which is surrounded by Portugal, France and Africa (Morocco). -

Annotated Checklist of the Myxomycetes (Slime Molds) Observed at the Gordon Natural Area West Chester University, PA) - Version I

West Chester University Digital Commons @ West Chester University Gordon Natural Area Biodiversity Studies Documents Gordon Natural Area Biodiversity Studies 7-24-2020 Annotated Checklist of the Myxomycetes (Slime Molds) Observed at the Gordon Natural Area West Chester University, PA) - Version I Nur Ritter Paige Vermeulen Maribeth Beatty Arianna Rivellini Alexandra Hodowanec Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcupa.edu/gna_bds_series Part of the Biodiversity Commons Annotated Checklist of the Myxomycetes (Slime Molds) Observed at the Gordon Natural Area West Chester University, PA) - Version I Description This checklist was compiled from Gordon Natural Area (GNA) Staff fieldwork during 2017-2020, augmented by photos from students and visitors to the GNA. The checklist contains 34 species in 18 Genera and 11 Families. Common Names Common names marked with an asterisk are those that were 'assigned' to a species by GNA staff. 'Monthly Presence' Data were taken from four sources: 1) fieldwork in the GNA; 2) the mycological literature; 3) field trip data from the New Jersey Mycological Association, New York Mycological Society, and the Western Pennsylvania Mushroom Club (see References); and, 4) observations in iNaturalist for Pennsylvania and six 'nearby' states: Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, and Ohio; (Data last updated: 7/7/2020). Associated Plants' GNA data are from field observations from 2017 to present. 'Literature' data were primarily taken from the USDA National Fungus Collection's Fungus-Host database (https://nt.ars-grin.gov/fungaldatabases/fungushost/fungushost.cfm), supplemented by a small number of observations from the literature. Species in red are non- native to Pennsylvania. -

Persoonia V18n1.Pdf

Volume 18 2002-2005 AN INTERNATIONAL MYCOLOGICAL JOURNAL Persoonia Vol. 18 - 2002-2005 CONTENTS In memoriam R.A. Maas Geesteranus.. 149 In memoriam C. B. Ulj6 . 151 Aancn. D. K. & Th. W. Kuyper: A comparison of the application of a biological and phenetic ~pccie~ concept in the l/ebetoma cms111/i11ifor111e complex within a phylo- genetic framework . 285 Adamfik. S.: Studies on R11:.s11la cla,·ipes and related 1axa of R11ss11la ~lion Xeram - peli11ae with a predominantly olivaceous pileus .. 393 Alben6. E.O.. R. H. Petersen. K.W. Hughes & B. Lechner: Miscellaneous note.~ on Ple11ro111s . 55 Antonfn. V.: oles on the genus Fayodia ~.I. (Tricholomataceae) - 11. lypc studies of European species described in the genera Fayodia and Gam1111dia . 341 Arnolds, E.: Notulac ad floram agaricinam nccrlandicam - XXXIX . Bolbitizts ... 20 I Arnold • E.: Notulac ad noram agaricinam nccrlandicam - XL. c.:w combinations in Conocybe and Pholio1i11a . 225 Arnolds. E. & A. Hau~knccht: otulnc ad floram agaricinam ncerlandicam - XU. Co11ocybe and Pholiuti1111 . 239 Arnolds. E.J.M .. K.M. Lcclavathy & P. Manimohan: Pseudobaeospora la1•e11d11- lamellata. a new species from Kerala. India . 435 Bakker. H.C. den & M.E. Noordeloos: A revi ion of European specie., of l,ecci1111111 Gray and not~ on cxtnilimital species. 5 11 Banares. A. & E. Arnolds: J-lygrocybe 111011te1•erdae. a new species of subgenus C11plzn- phyllus (Agaricales) from the Canary Islands (Spain) . 135 Bandala. V. M,. L. Montoya & D. Jarvio: 1\vo interesting record) of Bolctes found in coffee plantations in eastern M exico . 365 Bas, C.: A reconnaissance of the genus Pse11dobaensf)ora in Europe I . -

M U S H R O O

M U S Jack O’lantern H 7311 Highway 100 R Nashville, TN 37221 615-862-8555 [email protected] www.wpnc.nashville.gov O List compiled by Deb Beazley, 1986,1993,2003,2006,2009, 2018 Photographs by Deb Beazley O M Green Spored Lepiota S Of Warner Parks Common Split Gill MUSHROOMS OF THE WARNER PARKS 200) Arched Earthstar Geastrum fornicatum 201) Rounded Earthstar Geastrum saccatum ** Remember: The Park is a delicate natural area. All plants, animals, and fungi are strictly protected. Collecting of anything is prohibited. Stalked Puffballs: Order Tulostomatales 202) Buried-stalk Puffball Tulostoma simulans Kingdom: Fungus Phylum: Ascomycota - Spores formed inside sac-like cells called asci; (also contains yeasts, False Truffles: Order Hymenogastrales bread molds, and powdery mildews) 203) Yellow Blob False Truffle Alpova luteus (trappei) Class: Discomycetes - Asci line the exposed surface of the fruiting body Bird’s Nest Fungi: Order Nidulariales Cup Fungi: Order Pizizales 204) White-egg Bird’s Nest Crucibulum laeve 1) Scarlet Cup Sarcoscypha coccinea 205) Splash Cups Cyathus stercoreus 2) Stalked Scarlet Cup Sarcoscypa occidentalis 206) Striated Splash Cups Cyathus striatus 3) Burn Site Shield Cup Ascoblus carbonazius Rounded Earthstar 4) Crustlike Cup Rhizina undalata Stinkhorns: Order Phallales 5) Devil’s Urn Urnula craterium 207) Pitted White Stinkhorn Phallus impudicus 6) Eyelash Cup Scutellinia scutellata 208) Elegant Stinkhorn Mutinus elegans 7) Ribbed-stalked Cup Helvella acetabulum 209) Lantern Stinkhorn Lysurus mokusin 8) Yellow Morel Morchella esculenta 9) Hairy Rubber Cup Bulgaria rufa Smuts, Rusts, Blights, and Wilts 210) Cedar Apple Rust Gymnosporangium juniperi-virginianae Earth Tongues: Order Helotiales 211) Corn Smut Ustilago maydis 10) Velvety Earth Tongue Trichoglossum hirsutum 11) Purple Jelly Drops Ascocoryne sarcoides Class: Myxomycetes 12) Yellow Fairy Cups Bisporella citrina Yellow Morel 13) Fairy Fan Spathularia sp. -

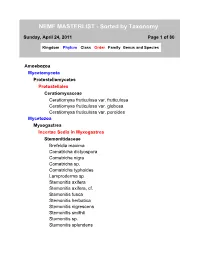

NEMF MASTERLIST - Sorted by Taxonomy

NEMF MASTERLIST - Sorted by Taxonomy Sunday, April 24, 2011 Page 1 of 80 Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Genus and Species Amoebozoa Mycetomycota Protosteliomycetes Protosteliales Ceratiomyxaceae Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa var. fruticulosa Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa var. globosa Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa var. poroides Mycetozoa Myxogastrea Incertae Sedis in Myxogastrea Stemonitidaceae Brefeldia maxima Comatricha dictyospora Comatricha nigra Comatricha sp. Comatricha typhoides Lamproderma sp. Stemonitis axifera Stemonitis axifera, cf. Stemonitis fusca Stemonitis herbatica Stemonitis nigrescens Stemonitis smithii Stemonitis sp. Stemonitis splendens Fungus Ascomycota Ascomycetes Boliniales Boliniaceae Camarops petersii Capnodiales Capnodiaceae Capnodium tiliae Diaporthales Valsaceae Cryphonectria parasitica Valsaria peckii Elaphomycetales Elaphomycetaceae Elaphomyces granulatus Elaphomyces muricatus Elaphomyces sp. Erysiphales Erysiphaceae Erysiphe polygoni Microsphaera alni Microsphaera alphitoides Microsphaera penicillata Uncinula sp. Halosphaeriales Halosphaeriaceae Cerioporiopsis pannocintus Hysteriales Hysteriaceae Glonium stellatum Hysterium angustatum Micothyriales Microthyriaceae Microthyrium sp. Mycocaliciales Mycocaliciaceae Phaeocalicium polyporaeum Ostropales Graphidaceae Graphis scripta Stictidaceae Cryptodiscus sp. 1 Peltigerales Collemataceae Leptogium cyanescens Peltigeraceae Peltigera canina Peltigera evansiana Peltigera horizontalis Peltigera membranacea Peltigera praetextala Pertusariales Icmadophilaceae Dibaeis baeomyces Pezizales